Abstract

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) open reading frame 63 (ORF63) protein is expressed during latency in human sensory ganglia. Deletion of ORF63 impairs virus replication in cell culture and establishment of latency in cotton rats. We found that cells infected with a VZV ORF63 deletion mutant yielded low titers of cell-free virus and produced very few enveloped virions detectable by electron microscopy compared with those infected with parental virus. Microarray analysis of cells infected with a recombinant adenovirus expressing ORF63 showed that transcription of few human genes was affected by ORF63; a heat shock 70-kDa protein gene was downregulated, and several histone genes were upregulated. In experiments using VZV transcription arrays, deletion of ORF63 from VZV resulted in a fourfold increase in expression of ORF62, the major viral transcriptional activator. A threefold increase in ORF62 protein was observed in cells infected with the ORF63 deletion mutant compared with those infected with parental virus. Cells infected with ORF63 mutants impaired for replication and latency (J. I. Cohen, T. Krogmann, S. Bontems, C. Sadzot-Delvaux, and L. Pesnicak, J. Virol. 79:5069-5077, 2005) showed an increase in ORF62 transcription compared with those infected with parental virus. In contrast, cells infected with an ORF63 mutant that is not impaired for replication or latency showed ORF62 RNA levels equivalent to those in cells infected with parental virus. The ability of ORF63 to downregulate ORF62 transcription may play an important role in virus replication and latency.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes chicken pox upon primary infection and then establishes latency in cranial nerve and dorsal root ganglia and can reactivate to cause shingles (herpes zoster). The lifetime risk of shingles is 10 to 20% for adults in the United States who are seropositive for VZV (14). Transcripts corresponding to VZV open reading frames (ORFs) 4, 21, 29, 62, 63, and 66 have been detected in latently infected human ganglia (8, 10, 24, 25, 36). ORF63 is the most frequently detected and most abundant of these transcripts (10, 25). ORF63 protein has also been detected in latently infected human (25, 31, 33) and rodent (11, 22) ganglia.

ORF63 encodes a virion tegument protein (28, 38), but the function of this protein is unclear. ORF63 protein enhances the activation of the minimal gI promoter by VZV ORF62 protein (32) and represses other viral genes (3, 20). In transient-transfection assays, ORF63 protein represses promoters containing typical TATA boxes (12), including VZV ORF4 and ORF28, heterologous viral promoters, and the human interleukin-8 promoter. The VZV gI promoter, which contains an atypical TATA box, is only slightly repressed. In contrast, ORF63 protein activates the cellular elongation factor 1 (EF-1) alpha promoter in some cell types (53).

A recombinant VZV in which 90% of both ORF63 and its duplicate gene, ORF70, are deleted is viable but impaired for growth in cell culture and latency in cotton rats (5). Analysis of additional ORF63 mutants showed that viruses that are impaired for replication in cell culture are also impaired for latency, while mutants that are not impaired for replication establish latencies at frequencies and copy numbers similar to those of parental virus (6).

In this study, we examined the effects of VZV ORF63 on virion production and regulation of viral and cellular gene expression. We found that ORF63 downregulates transcription of ORF62 and that cells infected with VZV mutants impaired for replication and latency show increased transcription of ORF62, while cells infected with a mutant that is not impaired express wild-type levels of ORF62.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human diploid fibroblasts (MRC-5) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Cell-free virus was prepared from VZV-infected human diploid fibroblasts (49). Briefly, equal numbers of cells were infected with cell-associated VZV and harvested when a near-maximal cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed, at approximately 36 h. Cell pellets were resuspended in SPGC (146 mM sucrose, 6 mM sodium glutamate, 10% fetal bovine serum in phosphate-buffered saline) and disrupted by sonication, and the sonicate was centrifuged at 1,400 × g (3,000 rpm) for 10 min. The supernatant was used as the source of cell-free virus. VZV ROka (recombinant Oka), ROka63D (5), ROka63-AccI, ROka-63-5M, and ROka63-KpnI (6) were grown in human melanoma (MeWo) cells by cocultivation of infected and uninfected cells. Recombinant adenoviruses Ad63, expressing ORF63 and green fluorescent protein (GFP), and Adblank, expressing GFP alone, were constructed as described previously (17), with modifications (40, 48). All adenovirus constructs were grown in human kidney epithelial 293 cells.

Electron microscopy.

Melanoma cells were infected with ROka or ROka63D at a ratio of one infected cell to six uninfected cells. When an extensive CPE developed (48 h postinfection for ROka or 72 h for ROka63D), cells were scraped into phosphate-buffered saline and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at 4°C. Cell pellets were washed three times in cacodylate buffer and stored overnight at 4°C before postfixation in 1% osmium tetroxide. Cells were stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate, dehydrated in graded ethanols, and embedded in plastic resin. Ultrathin sections were collected, mounted on 200 mesh copper grids, and stained with Reynold's lead citrate. The grids were examined with a Hitachi H-7000 transmission electron microscope.

Immunoblotting.

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), and proteins were separated on 4 to 20% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and detected with a polyclonal antibody to VZV ORF63 protein (38), followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) or with a monoclonal antibody to VZV glycoprotein E (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Human gene microarray analysis.

Human diploid fibroblasts were infected with Ad63 or Adblank at a multiplicity of infection of 10. Infection of virtually all cells was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy showing GFP expression. Forty-eight hours after infection, cells were harvested and stored as cell pellets at −70°C. Four identical experiments were performed on different days, and the cell pellets were processed in parallel.

Total RNA was extracted from the cell pellets using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Double-stranded DNA was synthesized using Superscript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and a T7-(dT)24 primer (Proligo, Boulder, CO), followed by Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. The cDNA was used as a template for in vitro transcription of biotin-labeled RNA using a BioArray high-yield RNA labeling kit (Enzo, Farmingdale, NY). Labeled RNA was fragmented in a buffer containing 200 mM Tris acetate (pH 8.1), 500 mM potassium acetate, and 150 mM magnesium acetate and hybridized to U133A GeneChips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA).

Data were transferred to the NIHLIMS Affymetrix microarray database (http://abs.cit.nih.gov/geneexpression.html). Data were analyzed using the MSCL Analyst's Toolbox (J. Barb and P. Munson, 2004; available at http://abs.cit.nih.gov) and the JMP statistical software (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC). Affymetrix MAS5 signal values were retrieved, and an adaptive variance-stabilizing, quantile-normalizing data transformation, termed SSG, was applied (P. J. Munson, 2001; available at http://www.stat.berkeley.edu/∼terry/zarray/Affy/GL_Workshop/genelogic2001.html). This transformation normalizes data obtained from chips over the full range of data and makes the variance of replicates nearly uniform over expression levels. Data were inspected for outliers using a principal component analysis with the transformed data. The study consisted of three treatment types: Ad63 (n = 4), Adblank (n = 4), and mock (n = 3). Comparison between treatments used a one-way analysis of variance with the transformed, normalized data. The P values for each probe set were collected, and the corresponding false-discovery rate (1) values were computed. Log (n-fold) change values were computed as the difference between the average Ad63 and Adblank values or between the Adblank and mock values. ORF63-regulated genes were defined as those with a >2-fold change in either direction between Ad63 and Adblank and a false-discovery rate of <20%. GO-SCAN (J. Barb, H. Schindel, and P. Munson, 2004; http://goscan.cit.nih.gov) computed all gene ontology terms that were associated with ORF63-regulated genes significantly more often than would be expected by chance. The predominant gene ontology terms were used to organize the list of up- or downregulated genes.

VZV gene array analysis.

Melanoma cells were infected with ROka63D at a 1:3 ratio of infected to uninfected cells or with ROka at ratios between 1:800 and 1:10. At 48 h postinfection, cells were harvested and an aliquot was used for immunoblot analysis. The remainder of the cell pellet was stored at −70°C until RNA was extracted. Total RNA was prepared as described above, and poly(A) RNA was selected using a Nucleotrap kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Poly(A) RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed to cDNA, which was radiolabeled and hybridized to VZV arrays as described previously (9). Labeled cDNA obtained from three independent infections was hybridized to a total of 10 arrays for cells infected with ROka and 6 arrays for cells infected with ROka63D.

Intensity values for each spot on the array were determined using a phosphorimager. Values were normalized to those of actin targets present on each array, and normalized values for replicate arrays were averaged. For ORFs represented by more than one target on the array, the values for all targets were averaged together to generate one value for the ORF. The relative expression levels were obtained by dividing the value for each ORF from the ROka63D arrays by the corresponding value from the ROka arrays. The average of all relative expression values was then calculated.

Real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR amplification was performed using 10 ng of each purified cDNA or 10% of each reverse transcription (RT) reaction mixture. Primers and fluorogenic probes were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Primer probe sets Hs 00269023_s1 and Hs 99999905_m1 were used to amplify the human histone H2b and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) genes, respectively. Primers HSPA1A-AF (5′ GCCGGCCTACTTCAACGA 3′) and HSPA1A-AR (5′ CGATCACACCCGCATCCTT 3′) and probe HSPA1A-AM1 (5′ CAGCGCAGGCCAC 3′) were used to amplify the human HSPA1A gene. Primers and probes designed to amplify the VZV ORF62 and gB genes have been described previously (27, 43).

PCRs were run on an ABI 7700 instrument, and data were analyzed using Sequence Detector software (Applied Biosystems). Differences (n-fold) between samples were calculated using the standard-curve method and/or the 2−ΔΔCt method (30).

Protein labeling and immunoprecipitation.

Melanoma cells were infected with ROka or ROka63D as described above. At 44 h postinfection, the cells were radiolabeled in medium containing 200 μCi/ml of [35S]methionine (Translabel; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) for 4 h. Cells were lysed on ice in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing complete protease inhibitor (Roche), 0.1 mM TLCK (Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine-chloromethyl ketone), and 0.1 mM TPCK (N-tosyl-l-phenylalanine-chloromethyl ketone) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Radioactivity in the lysates was measured, and equal numbers of counts from each lysate were used for immunoprecipitations. Lysates were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibody to ORF62 (a kind gift from Paul R. Kinchington, University of Pittsburgh) or with a monoclonal antibody to gE (Chemicon), and the immune complexes were precipitated with protein G-Sepharose (Amersham). Proteins were separated on 4 to 20% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and autoradiography was performed. A PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Piscataway, NJ) were used to quantify radioactivity in the protein bands.

RESULTS

Cells infected with a VZV ORF63 deletion mutant produce few intracellular virions and yield little cell-free virus.

Cells infected with ROka63D produced multinucleate syncytia similar to those formed by ROka-infected cells. However, ROka63D-infected cells yielded lower titers (6.5 × 101 to 1.2 × 102 PFU/ml) of cell-free virus than ROka-infected cells (3.3 × 104 to 3.6 × 104 PFU/ml) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Cell-free virus titers obtained by sonication of ROka- or ROka63D-infected human diploid fibroblasts

| Expt | Titer (PFU/ml) after sonication of fibroblasts infected witha:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| ROka | ROka63D | |

| 1 | 3.3 × 104 | 6.5 × 101 |

| 2 | 3.6 × 104 | 9.0 × 101 |

| 3 | ND | 2.0 × 101 |

| 4 | ND | 1.2 × 102 |

| Avg | 3.5 × 104 | 7.4 × 101 |

Titers were measured by plaque assay on melanoma cells. ND, not done.

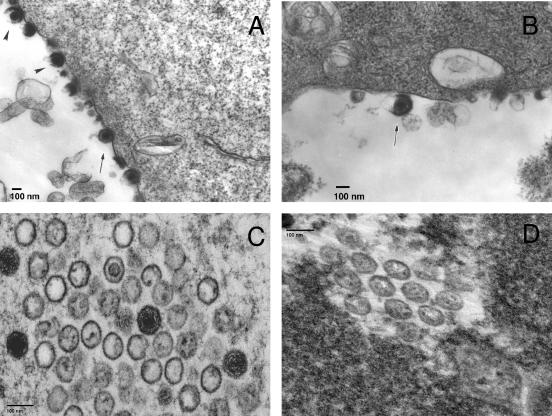

To investigate why little cell-free virus was obtained from cells infected with ROka63D, we examined ROka- and ROka63D-infected human melanoma cells by transmission electron microscopy. ROka-infected cells contained numerous enveloped virions on the plasma membrane (Fig. 1A) as well as paracrystalline arrays of nucleocapsids in the nucleus (Fig. 1C). Some nucleocapsids had electron-dense cores, while others were empty. Virions were located within the cell or attached to cell membranes. In contrast, ROka63D-infected cells contained rare virus particles at the cell surface (Fig. 1B) and few nucleocapsids in the nucleus (Fig. 1D) despite the extensive CPE observed by light microscopy. The sizes and appearances of the mature ROka63D virions were similar to those of ROka, with a diameter of 150 to 180 nm.

FIG. 1.

Transmission electron micrographs of melanoma cells 48 h after infection with ROka (A and C) or 72 h after infection with ROka63D (B and D). A ROka-infected cell contains enveloped virions (A, arrow and arrowheads), while a ROka63D-infected cell contains few virions (B, arrow). A large paracrystalline array of nucleocapsids is seen in the nucleus of a ROka-infected cell (C), while a ROka63D-infected cell shows fewer nucleocapsids (D).

The VZV ORF63 protein affects transcription of a small number of human genes.

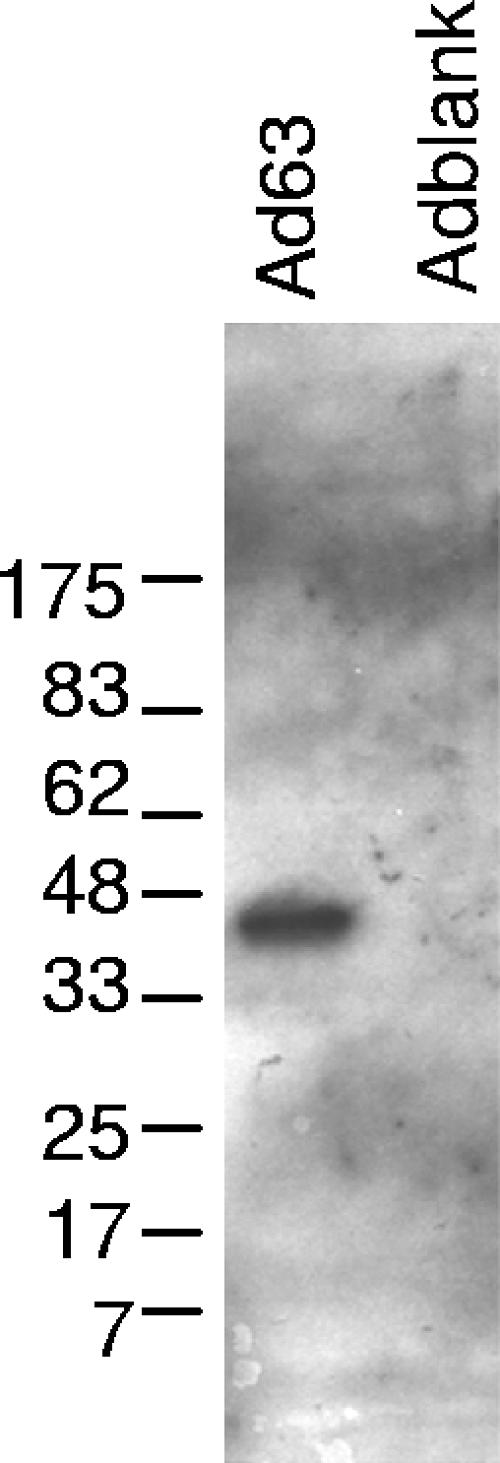

To study the effect of ORF63 protein on human cellular transcription, we compared gene expression levels in cells infected with a recombinant, replication-defective adenovirus expressing VZV ORF63 (Ad63) or a control adenovirus (Adblank). We chose this approach, rather than comparing ROka and ROka63D, because the impaired growth of the ROka63D mutant would be expected to cause a disproportionate contribution of uninfected cells to the microarray analysis. In contrast, Ad63 and Adblank grow to equal titers in vitro. Ad63-infected cells express a protein of approximately 45 kDa that reacts with rabbit antibody to VZV ORF63 protein (Fig. 2). Like ORF63 protein produced in VZV-infected cells, the ORF63 protein synthesized by Ad63 is phosphorylated (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

VZV ORF63 protein expression by recombinant adenovirus. Human diploid fibroblasts were infected with the replication-defective adenoviruses Ad63 (containing VZV ORF63) or Adblank (containing no insert). Forty-eight hours after infection, cells were harvested and lysates were used for immunoblotting with rabbit polyclonal antibody to the ORF63 protein.

Seventy-one of approximately 33,000 genes were upregulated more than twofold (ratio of Ad63 to Adblank, 2.1 to 7.3) in Ad63-infected cells relative to that in Adblank-infected cells, and 23 genes were downregulated more than twofold (ratio of Ad63 to Adblank, 0.06 to 0.48) (Table 2). Gene ontogeny analysis indicated that the predominant categories for both upregulated and downregulated genes were chromatin and transcription/transcriptional regulation.

TABLE 2.

Genes induced or suppressed more than twofold in human fibroblasts infected with Ad63 compared with those infected with Adblank

| Affymetrix designation | Name | Entrez gene no. | Ad63/Adblank ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatin | |||

| 208180_s_at | Histone 1, H4h | 8365 | 4.92 |

| 202708_s_at | Histone 2, H2be | 8349 | 3.60 |

| 206110_at | Histone 1, H3h | 8357 | 3.54 |

| 208808_s_at | High-mobility group box 2 | 3148 | 3.16 |

| 208579_x_at | H2B histone family, member S | 54145 | 2.96 |

| 209911_x_at | Histone 1, H2bd | 3017 | 2.77 |

| 209806_at | Histone 1, H2bk | 85236 | 2.46 |

| Transcription/transcriptional regulation | |||

| 210734_x_at | MAX protein | 4149 | 3.71 |

| 36711_at | v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma Oncogene homolog F (avian) | 23764 | 3.67 |

| 219848_s_at | Zinc finger protein 432 | 9668 | 2.84 |

| 218249_at | Zinc finger, DHHC domain containing 6 | 64429 | 2.77 |

| 203588_s_at | Transcription factor Dp-2 (E2F dimerization partner 2) | 7029 | 2.67 |

| 205690_s_at | Maternal-G10 transcript | 8896 | 2.66 |

| 203359_s_at | c-myc-binding protein | 26292 | 2.56 |

| 209966_x_at | Estrogen-related receptor gamma | 2104 | 2.51 |

| 200896_x_at | Hepatoma-derived growth factor (high-mobility group protein 1-like) | 3068 | 2.38 |

| 201930_at | MCM6 minichromosome maintenance-deficient 6 (MIS5 homolog, Schizosaccharomyces pombe) | 4175 | 2.33 |

| 215438_x_at | G1 to S phase transition 1 | 2935 | 2.25 |

| 202364_at | MAX interacting protein 1 | 4601 | 2.20 |

| 209187_at | Downregulator of transcription 1, TBP binding (negative cofactor 2) | 1810 | 2.18 |

| 207781_s_at | Zinc finger protein 6 (CMPX1) | 7552 | 2.14 |

| 203177_x_at | Transcription factor A, mitochondrial | 7019 | 2.11 |

| 212347_x_at | MAX dimerization protein 4 | 10608 | 2.01 |

| 206745_at | Homeobox C11 | 3227 | 0.49 |

| 222227_at | Zinc finger protein 236 | 7776 | 0.43 |

| 204610_s_at | Hepatitis delta antigen-interacting protein A | 11007 | 0.31 |

| 207980_s_at | Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator, with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain, 2 | 10370 | 0.27 |

| 213768_s_at | Achaete-scute complex-like 1 (Drosophila) | 429 | 0.24 |

| Intracellular | |||

| 204133_at | RNA, U3 small nucleolar interacting protein 2 | 9136 | 4.94 |

| 204833_at | APG12 autophagy 12-like (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | 9140 | 4.33 |

| 218481_at | Exosome component Rrp46 | 56915 | 4.01 |

| 208499_s_at | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 3 | 5611 | 4.00 |

| 219862_s_at | Nuclear prelamin A recognition factor | 26502 | 3.64 |

| 202960_s_at | Methylmalonyl coenzyme A mutase | 4594 | 3.14 |

| 216977_x_at | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide A′ | 6627 | 2.86 |

| 205462_s_at | Hippocalcin-like 1 | 3241 | 2.81 |

| 207390_s_at | Smoothelin | 6525 | 2.50 |

| 221479_s_at | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa interacting protein 3-like | 665 | 2.46 |

| 201948_at | Nucleolar GTPase | 29889 | 2.40 |

| 201057_s_at | Golgi autoantigen, golgin subfamily b, macrogolgin (with transmembrane signal), 1 | 2804 | 2.21 |

| 209155_s_at | 5′-Nucleotidase, cytosolic II | 22978 | 2.21 |

| 202782_s_at | Skeletal-muscle- and kidney-enriched inositol phosphatase | 51763 | 2.20 |

| 217689_at | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 1 | 5770 | 2.19 |

| 218715_at | Hepatocellular carcinoma-associated antigen 66 | 55813 | 2.13 |

| 200703_at | Dynein, cytoplasmic, light polypeptide 1 | 8655 | 2.09 |

| 213313_at | rab6 GTPase-activating protein (GAP and centrosome associated) | 23637 | 2.05 |

| 209447_at | Spectrin repeat-containing, nuclear envelope 1 | 23345 | 2.05 |

| 207105_s_at | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit, polypeptide 2 (p85 beta) | 5296 | 0.48 |

| 200740_s_at | SMT3 suppressor of mif two 3 homolog 1 (yeast) | 6612 | 0.44 |

| 203863_at | Actinin, alpha 2 | 88 | 0.43 |

| 207935_s_at | Keratin 13 | 3860 | 0.39 |

| 200800_s_at | Heat shock 70-kDa protein 1A | 3303 | 0.06 |

| Other/unclassified | |||

| 216913_s_at | KIAA0690 protein | 23223 | 7.32 |

| 211574_s_at | Membrane cofactor protein (CD46, trophoblast-lymphocyte cross-reactive antigen) | 4179 | 5.83 |

| 210350_x_at | Inhibitor of growth family, member 1 | 3621 | 5.12 |

| 221005_s_at | Phosphatidylserine synthase 2 | 81490 | 4.63 |

| 201965_s_at | KIAA0625 protein | 23064 | 3.93 |

| 214435_x_at | v-ral simian leukemia viral oncogene homolog A (ras related) | 5898 | 3.37 |

| 201014_s_at | Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase | 10606 | 3.08 |

| 218978_s_at | Mitochondrial solute carrier protein | 51312 | 3.06 |

| 204784_s_at | Myeloid leukemia factor 1 | 4291 | 3.00 |

| 209643_s_at | Phospholipase D2 | 5338 | 2.88 |

| 203162_s_at | Katanin p80 (WD repeat-containing) subunit B 1 | 10300 | 2.87 |

| 222351_at | Protein phosphatase 2 (formerly 2A), regulatory subunit A (PR 65), beta isoform | 5519 | 2.85 |

| 214290_s_at | Homo sapiens similar to H2B histone family, member F (LOC350696), mRNA | 343176 | 2.60 |

| 217039_x_at | ELK1, member of ETS oncogene family | 2002 | 2.57 |

| 210105_s_at | FYN oncogene related to SRC, FGR, YES | 2534 | 2.56 |

| 218107_at | WD repeat domain 26 | 80232 | 2.49 |

| 209111_at | Ring finger protein 5 | 6048 | 2.48 |

| 218277_s_at | DEAH (Asp-Glu-Ala-His) box polypeptide 40 | 79665 | 2.36 |

| 205508_at | Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type I, beta | 6324 | 2.23 |

| 212293_at | Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 1 | 204851 | 2.21 |

| 202129_s_at | RIO kinase 3 (yeast) | 8780 | 2.17 |

| 221492_s_at | Autophagy Apg3p/Aut1p-like | 64422 | 2.15 |

| 212689_s_at | Jumonji domain containing 1 | 55818 | 2.13 |

| 204547_at | RAB40B, member RAS oncogene family | 10966 | 2.11 |

| 200946_x_at | Glutamate dehydrogenase 1 | 2746 | 2.06 |

| 222235_s_at | Chondroitin sulfate GalNAcT-2 | 55454 | 2.05 |

| 221190_s_at | Colon cancer-associated protein Mic1 | 29919 | 2.04 |

| 214390_s_at | Branched-chain aminotransferase 1, cytosolic | 586 | 2.02 |

| 209332_s_at | MAX protein | 4149 | 2.01 |

| 216383_at | Ribosomal protein L18a | 6142 | 0.47 |

| 213727_x_at | Metallophosphoesterase | 65258 | 0.47 |

| 204340_at | Chromosome X open reading frame 12 | 8269 | 0.46 |

| 204565_at | Thioesterase superfamily member 2 | 55856 | 0.45 |

| 210822_at | Similar to 60S ribosomal protein L13 (A52) | 283345 | 0.45 |

| 219706_at | Chromosome 20 open reading frame 29 | 55317 | 0.44 |

| 216105_x_at | Protein phosphatase 2A, regulatory subunit B′ (PR 53) | 5524 | 0.41 |

| 203700_s_at | Deiodinase, iodothyronine, type II | 1734 | 0.40 |

| 213398_s_at | HCDI protein | 56948 | 0.39 |

| 216714_at | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 13 | 6357 | 0.31 |

| 204602_at | Dickkopf homolog 1 (Xenopus laevis) | 22943 | 0.30 |

| 204546_at | KIAA0513 gene product | 9764 | 0.29 |

| 207032_s_at | Cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 | 167 | 0.28 |

Histone genes, particularly members of the histone H2b family, were overrepresented among the upregulated genes in cells infected with Ad63 compared with those in Adblank-infected cells (Table 2). Real-time RT-PCR experiments confirmed the upregulation of histone H2be to be an average of 3.9-fold (Table 3). The most strongly downregulated gene in cells infected with Ad63 compared with those infected with Adblank was the gene encoding heat shock 70-kDa protein 1A (HSPA1A), which was downregulated an average of 16.7-fold (ratio of Ad63 to Adblank, 0.06). Real-time RT-PCR showed the downregulation of the HSPA1A gene to be an average of 5.0-fold (Table 3). Of note, the real-time PCR primers do not distinguish between the HSPA1A gene and the duplicate HSPA1B gene, which encodes an identical protein.

TABLE 3.

Relative expression of selected cellular genes in Ad63- versus Adblank-infected human fibroblasts and in ROka63D- versus ROka-infected melanoma cells

| Gene | Expression ratio

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ad63/Adblank

|

ROka63D/ROka by real-time PCR (n = 2) | ||

| Array (n = 4) | Real-time PCR (n = 5) | ||

| Histone H2be gene | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| Gene encoding heat shock 70-kDa protein 1A | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 69.8 ± 26.1 |

Cells infected with an ORF63 deletion mutant upregulate HSPA1A compared with cells infected with parental virus.

We also examined the expression levels of selected genes in the context of VZV infection. We compared transcription levels of histone H2be and HSPA1A in melanoma cells infected with ROka or ROka63D. Because ROka63D grows to lower titers than ROka, we infected cells with various amounts of the two viruses and estimated the extent of infection by comparing viral glycoprotein E (gE) expression levels by immunoblot analysis. At 48 h postinfection, cells infected with ROka63D at a ratio of 1 infected cell to 3 uninfected cells produced approximately as much gE as cells infected with ROka at a ratio of 1 infected cell to 22 uninfected cells (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

(A) Normalization of gE expression levels in VZV-infected cells. Melanoma cells were infected with ROka63D or ROka at the indicated ratios of infected to uninfected cells as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were harvested 48 h postinfection, and lysates were used for immunoblotting with monoclonal antibody to VZV gE. (B) Relative expression levels of each VZV ORF in ROka63D- versus ROka-infected cells. Cells were harvested 48 h postinfection, and mRNA was isolated and used to synthesize radiolabeled cDNA, which was hybridized to VZV arrays. Each point indicates the relative expression level of the respective ORF in ROka63D-infected cells versus ROka-infected cells. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. The thick horizontal line represents the mean relative expression level for all ORFs, and the shaded region indicates 1 standard error of the mean. The control targets (left to right) are actin, GAPDH, no DNA, and a negative-control, plasmid-derived sequence (tet). The data represent the average of three independent experiments comprising a total of 10 ROka arrays and 6 ROka63D arrays.

HSPA1A was upregulated an average of 70-fold in cells infected with ROka63D compared to those infected with ROka (Table 3). This result is compatible with the downregulation of HSPA1A during Ad63 infection compared with Adblank infection. In contrast, while histone H2be was upregulated in cells infected with Ad63 versus those infected with Adblank (see above), its expression levels were equal in ROka63D- and ROka-infected cells.

Deletion of ORF63 from VZV results in upregulation of ORF62 expression.

Because expression of ORF63 by recombinant adenovirus had a modest effect on a relatively small set of cellular genes, we postulated that ORF63 may be more important in regulating viral gene expression. To investigate the effect of ORF63 on viral gene regulation, we used VZV expression arrays (9) to compare VZV gene expression levels in ROka- versus ROka63D-infected cells. We infected melanoma cells with ROka or ROka63D and equalized infectivities by gE expression as described above. We also infected cells with equal titers of ROka or ROka63D and found that the relative expression levels of VZV ORF transcripts in cells was not dependent on whether we used cells infected with equal titers of virus or cells expressing equal levels of gE. The mean relative expression level of all VZV ORFs in ROka63D- versus ROka-infected cells was 1.5 ± 0.8 (Fig. 3B and Table 4). This was likely due to the larger inoculum of ROka63D used to obtain approximately the same level of gE expression in some of the experiments. In contrast, the mean relative expression level of ORF62 was 6.2 ± 0.8, or 4.1-fold higher than the mean level of all ORFs. The mean relative expression level of ORF63 was approximately 0, because the gene was deleted from ROka63D, and that for gE (ORF68) was close to 1.

TABLE 4.

Relative expression levels of VZV ORFs during ROka63D or ROka infection of melanoma cellsa

| ORF | ROka63D expression level (rank) | ROka expression level (rank) | ROka63D/ROka ratio | ORF | ROka63D expression level (rank) | ROka expression level (rank) | ROka63D/ROka ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62 | 6.39 (1) | 1.03 (5) | 6.21 | 67 | 0.50 (37) | 0.55 (20) | 0.91 | |

| 9 | 4.29 (2) | 2.94 (1) | 1.46 | 28 | 0.48 (38) | 0.33 (38) | 1.46 | |

| 50 | 3.16 (3) | 1.10 (4) | 2.86 | 35 | 0.47 (39) | 0.31 (39) | 1.50 | |

| 4 | 2.34 (4) | 0.90 (9) | 2.59 | 34 | 0.38 (40) | 0.24 (48) | 1.57 | |

| 64 | 2.32 (5) | 1.60 (2) | 1.45 | 47 | 0.35 (41) | 0.26 (45) | 1.37 | |

| 49 | 1.99 (6) | 0.84 (10) | 2.37 | 68 | 0.35 (42) | 0.39 (29) | 0.90 | |

| 61 | 1.60 (7) | 0.76 (13) | 2.10 | 27 | 0.33 (43) | 0.31 (40) | 1.06 | |

| 57 | 1.41 (8) | 0.93 (8) | 1.51 | 60 | 0.31 (44) | 0.27 (44) | 1.15 | |

| 24 | 1.40 (9) | 0.70 (16) | 1.99 | 31 | 0.29 (46) | 0.34 (36) | 0.85 | |

| 36 | 1.30 (10) | 0.81 (11) | 1.60 | 44 | 0.28 (47) | 0.33 (37) | 0.85 | |

| 48 | 1.23 (11) | 0.63 (17) | 1.95 | 37 | 0.27 (48) | 0.30 (41) | 0.89 | |

| 3 | 1.17 (12) | 0.74 (15) | 1.59 | 42 | 0.26 (49) | 0.18 (56) | 1.48 | |

| 33 | 1.08 (13) | 0.61 (19) | 1.77 | 10 | 0.25 (50) | 0.28 (43) | 0.90 | |

| 1 | 0.88 (15) | 0.55 (21) | 1.61 | 52 | 0.25 (51) | 0.14 (60) | 1.84 | |

| 41 | 0.84 (16) | 0.94 (7) | 0.90 | 46 | 0.25 (52) | 0.20 (54) | 1.24 | |

| 59 | 0.84 (17) | 0.75 (14) | 1.12 | 26 | 0.24 (53) | 0.20 (53) | 1.19 | |

| 7 | 0.84 (18) | 0.52 (23) | 1.60 | 21 | 0.24 (54) | 0.18 (55) | 1.29 | |

| 53 | 0.80 (19) | 0.44 (25) | 1.84 | 19 | 0.22 (55) | 0.21 (50) | 1.05 | |

| 54 | 0.79 (20) | 0.43 (26) | 1.86 | 40 | 0.21 (56) | 0.21 (51) | 0.97 | |

| 58 | 0.78 (21) | 0.61 (18) | 1.28 | 6 | 0.16 (57) | 0.15 (59) | 1.11 | |

| 14 | 0.75 (22) | 0.29 (42) | 2.59 | 30 | 0.16 (58) | 0.20 (52) | 0.80 | |

| 29 | 0.70 (23) | 0.53 (22) | 1.32 | 65 | 0.15 (59) | 0.13 (62) | 1.17 | |

| 38 | 0.67 (24) | 0.78 (12) | 0.86 | 5 | 0.15 (60) | 0.13 (61) | 1.08 | |

| 16 | 0.63 (25) | 0.38 (30) | 1.66 | 8 | 0.15 (61) | 0.17 (57) | 0.87 | |

| 15 | 0.59 (26) | 0.41 (28) | 1.43 | 63 | 0.14 (62) | 1.57 (3) | 0.09 | |

| 11 | 0.58 (27) | 0.35 (33) | 1.66 | 43 | 0.14 (63) | 0.12 (63) | 1.21 | |

| 2 | 0.57 (28) | 0.36 (31) | 1.57 | 22 | 0.14 (64) | 0.11 (65) | 1.25 | |

| 13 | 0.56 (29) | 0.25 (47) | 2.25 | 45 | 0.14 (65) | 0.09 (68) | 1.60 | |

| 32 | 0.55 (30) | 0.35 (34) | 1.58 | 39 | 0.13 (66) | 0.11 (66) | 1.22 | |

| 23 | 0.55 (31) | 0.42 (27) | 1.29 | 56 | 0.13 (67) | 0.08 (69) | 1.55 | |

| 51 | 0.55 (32) | 0.34 (35) | 1.62 | 25 | 0.13 (68) | 0.12 (64) | 1.10 | |

| 66 | 0.52 (33) | 0.16 (58) | 3.25 | 17 | 0.10 (69) | 0.09 (67) | 1.07 | |

| 12 | 0.52 (34) | 0.22 (49) | 2.37 | 55 | 0.09 (70) | 0.08 (70) | 1.18 | |

| 18 | 0.51 (35) | 0.45 (24) | 1.13 | |||||

| 20 | 0.50 (36) | 0.35 (32) | 1.40 | Mean | 1.52 |

Values are normalized to actin expression.

Real-time RT-PCR confirmed the increase in ORF62 transcription in ROka63D-infected cells compared to that in ROka-infected cells. We used a portion of the RNA from one of the array experiments (Fig. 3B), as well as RNA from two new independent experiments, to perform real-time RT-PCR for ORF62 and for ORF31 (gB) as a control. The expression level of ORF62 was 2.1-fold higher in ROka63D- than in ROka-infected cells (Table 5), while the expression level of ORF31 was 0.3-fold as high. The ratio of the expression level of ORF62 to ORF31 by real-time RT-PCR (6.2-fold) was similar to that of ORF62 to ORF31 on the arrays (7.3-fold).

TABLE 5.

Relative expression levels of selected VZV genes in cells infected with VZV ORF63 mutants versus cells infected with ROka

| Expt and mutanta | Expression level relative to that of ROka-infected cells

|

Ratio

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF62 | ORF31 (gB) | ORF68 (gE) | ORF62/ ORF31 | ORF62/ ORF68 | |

| VZV array | |||||

| ROka63D (n = 6) | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 7.3 | ||

| RT-PCR | |||||

| ROka63D (n = 3) | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 6.2 | ||

| ROka63-AccI (n = 5) | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 3.2 | ||

| ROka63-5M (n = 5) | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 2.7 | ||

| ROka63-KpnI (n = 5) | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 1.0 | ||

| Protein immunoprecipitation | |||||

| ROka63D (n = 3) | 0.72 | 0.26 | 3.06 ± 0.99 | ||

n, number of experiments.

A similar increase in ORF62 protein production was noted in cells infected with ROka63D compared with that in parental virus. We infected melanoma cells with ROka or ROka63D and labeled the cells with [35S]methionine for the final 4 h of infection. In these experiments, ROka63D-infected cells showed fewer syncytia than cells infected with ROka at the time of harvest, and cells infected with ROka63D produced less gE, consistent with the less-extensive infection. However, the amounts of ORF62 protein were approximately equal. The ORF62 protein expression level was threefold higher in ROka63D-infected cells than in ROka-infected cells when normalized to gE protein (Table 5).

Transcription of ORF62 in cells infected with ORF63 mutant viruses correlates with levels of virus replication in vitro and latency in rodents.

A VZV mutant lacking the carboxy-terminal 70 amino acids of ORF63 protein (ROka63-KpnI) is not impaired either for growth in cell culture or for latency in cotton rats (6). In contrast, VZV mutants lacking the carboxy-terminal 107 amino acids of ORF63 protein (ROka-63AccI) or with point mutations substituting alanine for serine or threonine at five phosphorylation sites in the carboxy-terminal half of the protein (ROka63-5M) are impaired both for replication in cell culture and for latency (6). Real-time RT-PCR showed that ORF62 transcription levels were similar in ROka63-KpnI- and ROka-infected cells, whereas ORF62 transcription levels in both ROka63-AccI- and ROka63-5M-infected cells were approximately twofold higher (Table 5).

The ratio of ORF62 transcription in ROka63D-infected cells to that in ROka-infected cells, normalized to ORF31 expression levels, was 6.2. The corresponding ratio for ROka63-AccI-infected cells was 3.2, and that for ROka63-5M-infected cells was 2.7. However, the ratio for ROka63-KpnI-infected cells was 1.0. Thus, the three mutants that are impaired for replication in vitro and latency in rodents (ROka63D, ROka63-AccI, and ROka63-5M) showed increased transcription levels of ORF62 relative to those of parental virus, while a mutant that has a wild-type phenotype in cell culture and latency (ROka63-KpnI) showed a level of ORF62 transcription similar to that of parental virus (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Diagram of ORF63 proteins produced by ROka and by ORF63 mutants and their phenotypes in cell culture and in animals. Replication values were determined by dividing the peak titer in mutant-infected cells by the peak titer in ROka-infected cells. Latency values were determined by dividing the percentage of animals latently infected with the mutant by the percentage of animals latently infected with ROka. Data in the replication and latency columns are derived from references 5 and 6. ORF62 expression values were determined by dividing (ORF62 copy number in mutant-infected cells/ORF62 copy number in ROka-infected cells) by (gB copy number in mutant-infected cells/gB copy number in ROka-infected cells). Data in the ORF62 expression column are derived from RT-PCR. ROka63D encodes a protein in which amino acids 24 to 268 are deleted, and codons 269 to 278 are out of frame. Numbers over the bar corresponding to ROka63-5M indicate sites of alanine substitution for serine or threonine.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that VZV deleted for ORF63 produced very few intact virions in infected cells and that very little cell-free virus could be obtained from these cells, despite extensive CPE. We showed that VZV ORF63 downregulates expression of VZV ORF62 and cellular HSPA1A in the context of VZV infection and that transcription of ORF62 correlates with the level of virus replication in cell culture and latency in rodents.

The impaired production of virions in ROka63D-infected cells suggests that efficient virion formation is not necessary for cell-to-cell spread of the virus in culture. Since ORF63 encodes a tegument protein (28), its localization in the virus may be required for efficient assembly of virions. Two VZV ORF47 protein kinase mutants demonstrate similar phenotypes, with growth kinetics similar to that of parental virus in cultured cells but with reduced growth in human skin xenografts (2). Both mutants produce fewer and slightly smaller viral particles than parental virus in both melanoma cells and human skin xenografts. Interestingly, the ORF47 protein kinase can phosphorylate ORF63 protein, and it is possible that the phenotype of the ORF47 mutant in skin xenografts is due in part to reduced phosphorylation of ORF63.

Expression of VZV ORF63 protein downregulated HSPA1A, a member of the heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) family. This family consists of at least 11 highly related genes (51). Numerous viruses, including VZV, other herpesviruses, and adenoviruses, have been reported to induce hsp70 mRNA and/or protein (39, 44, 46, 52). The antibodies and probes used in many of these studies detect multiple members of the hsp70 family and do not distinguish HSPA1A from the other members. Similarly, the microarray probes and PCR primers used in our studies do not distinguish between the HSPA1A gene and closely related hsp70 genes. While VZV has previously been reported to upregulate the hsp70 family of genes, it is not clear why ORF63 specifically downregulates one or more members of this family.

Expression of ORF63 by the recombinant adenovirus upregulated several histone genes. Like heat shock proteins, histones are members of highly conserved families. The main regulator of histone expression is the cell cycle, with new histone proteins being synthesized during S phase in coordination with DNA replication (34). Although viral infection can affect chromatin structure and histone modifications (18, 26, 50), there is little evidence for an effect on histone gene expression itself. Vaccinia virus infection upregulates several histone genes in microarray experiments (15, 16). The upregulation of histone H2be transcription by ORF63 was seen only in the context of recombinant adenovirus infection, not during VZV infection. Other VZV proteins may modulate the effect of ORF63 protein on histone H2be transcription.

Expression of VZV OR63 protein by a recombinant adenovirus affected the transcription of relatively few cellular genes in human fibroblasts. It is surprising that the significantly affected genes included members of highly redundant gene families. Neither the histone composition of DNA nor the cellular response to stress would be expected to change substantially through a difference in expression levels of only one of several apparently redundant genes. The relatively modest effect of ORF63 protein expression was borne out by additional experiments in which we infected SKNSH human neuroblastoma cells with Ad63 or Adblank and analyzed cellular transcription using Affymetrix U133 microarrays. In those experiments, no significant differences in expression levels of cellular genes were found between Ad63- and Adblank-infected cells (data not shown). VZV latency proteins have previously been shown to have different transcriptional activities in neuronal cells than in other cell types in transient-transfection studies. ORF63 protein activates the EF-1α promoter in melanoma cells but not in neuroblastoma cells (53). ORF29 protein augments the ability of ORF62 protein to transactivate the gI promoter in fibroblasts but inhibits the ability of ORF62 protein to activate the same promoter in neuronal (PC-12) cells (4). Thus, it is not surprising that we observed different transcriptional patterns associated with ORF63 protein in fibroblasts than in neuroblastoma cells.

Infection of cells with ROka63D resulted in a fourfold-higher ORF62 transcription level and a threefold-higher ORF62 protein expression level than infection with ROka. One explanation for the increase in the ORF62 expression level is that the deletion in ROka63D encompasses a negative regulatory element for ORF62. ORF62 and ORF63 are transcribed in opposite directions from a common intergenic region. The start of the deletion in ROka63D corresponds to −1443 from the ORF62 transcription start site (5). However, the region responsible for the basal activity of the ORF62 promoter has been shown in transient-transfection assays to be much more proximal, located downstream of position −200 from the transcription start site (35, 37, 42), making it unlikely that the deletion removes promoter sequences. In addition, the observation that cells infected with ROka63-5M (which has no deletion but five point mutations in ORF63) also showed increased transcription levels of ORF62, which suggests that the deletion in ROka63D did not remove a negative regulatory element for ORF62.

The increase in ORF62 expression in cells infected with ROka63D compared with that in cells infected with ROka suggests that one function of ORF63 protein is repression of ORF62 expression. ORF62 is an immediate-early gene (13, 47, 49) whose product activates transcription from numerous VZV promoters (19, 41). Repression of the ORF62 promoter by ORF63 was observed previously in transient-transfection assays in one report (20) but not in another (29). The herpes simplex virus homolog of the ORF63 protein, ICP22, can repress viral immediate-early promoters, including the promoter for ICP4, the homolog of the VZV ORF62 protein, in transient-transfection assays (45). In contrast to these transient-transfection studies, our experiments analyzed the effect of ORF63 in the context of the whole VZV genome, with levels of ORF63 appropriate for infected cells and with the ORF62 regulatory and coding sequences in the viral genome.

Compared with cells infected with ROka, cells infected with VZV ORF63 mutants that are impaired for latency in cotton rats (ROka63-AccI and ROka63-5M) showed an increase in ORF62 transcription similar to that seen for cells infected with ROka63D. In contrast, cells infected with a VZV mutant (ROka63-KpnI) that is not impaired for latency showed ORF62 transcription levels similar to those for cells infected with ROka. Comparison of ROka63-KpnI and ROka63-AccI suggests that the region between amino acids 170 and 208 is important for normal viral replication, establishment of latency, and repression of ORF62 (Fig. 4). Phosphorylation of threonine 171 and serines 181 and 186, which are located in this region, may play an important role in these functions. The ROka63-5M mutant, in which these residues are changed to alanines, has the same phenotype as the ROka63-AccI deletion mutant. ORF62, like ORF63, is expressed during latency (7, 25, 31, 33, 36). The inverse correlation between the establishment of latency in rodents and the level of ORF62 transcription further suggests that the repression of the ORF62 viral transactivator by ORF63 may contribute to the control of viral gene expression during latency.

ADDENDUM

Two recently published papers have included microarray analysis of VZV transcription. Jones and Arvin (21) reported that cells infected with a small-plaque mutant of VZV with a point mutation in ORF63 showed decreased levels of VZV ORF 28, −47, −51, and −67 transcripts and different levels of several cellular gene transcripts compared with cells infected with parental virus. Kennedy et al. (23) detected markedly fewer viral gene transcripts in astroglial cells infected with VZV strain Dumas than in melanoma cells infected with the same virus, despite similar levels of infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Schaack for help in constructing the recombinant adenoviruses.

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by grants AG06127 (D.H.G.) and NS 32623 (D.H.G. and R.J.C.) from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamini, Y., and Y. Hochberg. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 57:289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besser, J., M. Ikoma, K. Fabel, M. H. Sommer, L. Zerboni, C. Grose, and A. M. Arvin. 2004. Differential requirement for cell fusion and virion formation in the pathogenesis of varicella-zoster virus infection in skin and T cells. J. Virol. 78:13293-13305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bontems, S., E. Di Valentin, L. Baudoux, B. Rentier, C. Sadzot-Delvaux, and J. Piette. 2002. Phosphorylation of varicella-zoster virus IE63 protein by casein kinases influences its cellular localization and gene regulation activity. J. Biol. Chem. 277:21050-21060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucaud, D., H. Yoshitake, J. Hay, and W. Ruyechan. 1998. The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) open-reading frame 29 protein acts as a modulator of a late VZV gene promoter. J. Infect. Dis. 178(Suppl. 1):S34-S38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen, J. I., E. Cox, L. Pesnicak, S. Srinivas, and T. Krogmann. 2004. The varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 63 latency-associated protein is critical for establishment of latency. J. Virol. 78:11833-11840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen, J. I., T. Krogmann, S. Bontems, C. Sadzot-Delvaux, and L. Pesnicak. 2005. Regions of the varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 63 latency-associated protein important for replication in vitro are also critical for efficient establishment of latency. J. Virol. 79:5069-5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohrs, R. J., M. Barbour, and D. H. Gilden. 1996. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) transcription during latency in human ganglia: detection of transcripts mapping to genes 21, 29, 62, and 63 in a cDNA library enriched for VZV RNA. J. Virol. 70:2789-2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohrs, R. J., D. H. Gilden, P. R. Kinchington, E. Grinfeld, and P. G. E. Kennedy. 2003. Varicella-zoster virus gene 66 transcription and translation in latently infected human ganglia. J. Virol. 77:6660-6665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohrs, R. J., M. P. Hurley, and D. H. Gilden. 2003. Array analysis of viral gene transcription during lytic infection of cells in tissue culture with varicella-zoster virus. J. Virol. 77:11718-11732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohrs, R. J., J. Randall, J. Smith, D. H. Gilden, C. Dabrowski, H. van der Keyl, and R. Tal-Singer. 2000. Analysis of individual human trigeminal ganglia for latent herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acids using real-time PCR. J. Virol. 74:11464-11471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debrus, S., C. Sadzot-Delvaux, A. F. Nikkels, J. Piette, and B. Rentier. 1995. Varicella-zoster virus gene 63 encodes an immediate-early protein that is abundantly expressed during latency. J. Virol. 69:3240-3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Valentin, E., S. Bontems, L. Habran, O. Jolois, N. Markine-Goriaynoff, A. Vanderplasschen, C. Sadzot-Delvaux, and J. Piette. 2005. Varicella-zoster virus IE63 protein represses the basal transcription machinery by disorganizing the pre-initiation complex. Biol. Chem. 386:255-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forghani, B., R. Mahalingam, A. Vafai, J. W. Hurst, and K. W. Dupuis. 1990. Monoclonal antibody to immediate early protein encoded by varicella-zoster virus gene 62. Virus Res. 16:195-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gnann, J. W., Jr., and R. J. Whitley. 2002. Clinical practice. Herpes zoster. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:340-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerra, S., L. A. López-Fernández, R. Conde, A. Pascual-Montano, K. Harshman, and M. Esteban. 2004. Microarray analysis reveals characteristic changes of host cell gene expression in response to attenuated modified vaccinia virus Ankara infection of human HeLa cells. J. Virol. 78:5820-5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerra, S., L. A. López-Fernández, A. Pascual-Montano, M. Muñoz, K. Harshman, and M. Esteban. 2003. Cellular gene expression survey of vaccinia virus infection of human HeLa cells. J. Virol. 77:6493-6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He, T. C., S. Zhou, L. T. da Costa, J. Yu, K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1998. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2509-2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrera, F. J., and S. J. Triezenberg. 2004. VP16-dependent association of chromatin-modifying coactivators and underrepresentation of histones at immediate-early gene promoters during herpes simplex virus infection. J. Virol. 78:9689-9696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inchauspe, G., S. Nagpal, and J. M. Ostrove. 1989. Mapping of two varicella-zoster virus-encoded genes that activate the expression of viral early and late genes. Virology 173:700-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackers, P., P. Defechereux, L. Baudoux, C. Lambert, M. Massaer, M.-P. Merville-Louis, B. Rentier, and J. Piette. 1992. Characterization of regulatory functions of the varicella-zoster virus gene 63-encoded protein. J. Virol. 66:3899-3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones, J. O., and A. M. Arvin. 2005. Viral and cellular gene transcription in fibroblasts infected with small plaque mutants of varicella-zoster virus. Antivir. Res. 68:56-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy, P. G., E. Grinfeld, S. Bontems, and C. Sadzot-Delvaux. 2001. Varicella-zoster virus gene expression in latently infected rat dorsal root ganglia. Virology 289:218-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy, P. G., E. Grinfeld, M. Craigon, K. Vierlinger, D. Roy, T. Forster, and P. Ghazal. 2005. Transcriptomal analysis of varicella-zoster virus infection using long oligonucleotide-based microarrays. J. Gen. Virol. 86:2673-2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy, P. G., E. Grinfeld, and J. W. Gow. 1999. Latent varicella-zoster virus in human dorsal root ganglia. Virology 258:451-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kennedy, P. G. E., E. Grinfeld, and J. E. Bell. 2000. Varicella-zoster virus gene expression in latently infected and explanted human ganglia. J. Virol. 74:11893-11898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kent, J. R., P.-Y. Zeng, D. Atanasiu, J. Gardner, N. W. Fraser, and S. L. Berger. 2004. During lytic infection herpes simplex virus type 1 is associated with histones bearing modifications that correlate with active transcription. J. Virol. 78:10178-10186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimura, H., Y. Wang, L. Pesnicak, J. I. Cohen, J. J. Hooks, S. E. Straus, and R. K. Williams. 1998. Recombinant varicella-zoster virus glycoproteins E and I: immunologic responses and clearance of virus in a guinea pig model of chronic uveitis. J. Infect. Dis. 178:310-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinchington, P. R., D. Bookey, and S. E. Turse. 1995. The transcriptional regulatory proteins encoded by varicella-zoster virus open reading frames (ORFs) 4 and 63, but not ORF 61, are associated with purified virus particles. J. Virol. 69:4274-4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kost, R. G., H. Kupinsky, and S. E. Straus. 1995. Varicella-zoster virus gene 63: transcript mapping and regulatory activity. Virology 209:218-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lungu, O., C. A. Panagiotidis, P. W. Annunziato, A. A. Gershon, and S. J. Silverstein. 1998. Aberrant intracellular localization of varicella-zoster virus regulatory proteins during latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7080-7085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynch, J. M., T. K. Kenyon, C. Grose, J. Hay, and W. T. Ruyechan. 2002. Physical and functional interaction between the varicella zoster virus IE63 and IE62 proteins. Virology 302:71-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahalingam, R., M. Wellish, R. Cohrs, S. Debrus, J. Piette, B. Rentier, and D. H. Gilden. 1996. Expression of protein encoded by varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 63 in latently infected human ganglionic neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2122-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marzluff, W. F., P. Gongidi, K. R. Woods, J. Jin, and L. J. Maltais. 2002. The human and mouse replication-dependent histone genes. Genomics 80:487-498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKee, T. A., G. H. Disney, R. D. Everett, and C. M. Preston. 1990. Control of expression of the varicella-zoster virus major immediate early gene. J. Gen. Virol. 71:897-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meier, J. L., R. P. Holman, K. D. Croen, J. E. Smialek, and S. E. Straus. 1993. Varicella-zoster virus transcription in human trigeminal ganglia. Virology 193:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moriuchi, H., M. Moriuchi, and J. I. Cohen. 1995. Proteins and cis-acting elements associated with transactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) immediate-early gene 62 promoter by VZV open reading frame 10 protein. J. Virol. 69:4693-4701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ng, T. I., L. Keenan, P. R. Kinchington, and C. Grose. 1994. Phosphorylation of varicella-zoster virus open reading frame (ORF) 62 regulatory product by viral ORF 47-associated protein kinase. J. Virol. 68:1350-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohgitani, E., K. Kobayashi, K. Takeshita, and J. Imanishi. 1998. Induced expression and localization to nuclear-inclusion bodies of hsp70 in varicella-zoster virus-infected human diploid fibroblasts. Microbiol. Immunol. 42:755-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orlicky, D. J., and J. Schaack. 2001. Adenovirus transduction of 3T3-L1 cells. J. Lipid Res. 42:460-466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perera, L. P., J. D. Mosca, W. T. Ruyechan, and J. Hay. 1992. Regulation of varicella-zoster virus gene expression in human T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 66:5298-5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perera, L. P., J. D. Mosca, M. Sadeghi-Zadeh, W. T. Ruyechan, and J. Hay. 1992. The varicella-zoster virus immediate early protein, IE62, can positively regulate its cognate promoter. Virology 191:346-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pevenstein, S. R., R. K. Williams, D. McChesney, E. K. Mont, J. E. Smialek, and S. E. Straus. 1999. Quantitation of latent varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus genomes in human trigeminal ganglia. J. Virol. 73:10514-10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips, B., K. Abravaya, and R. I. Morimoto. 1991. Analysis of the specificity and mechanism of transcriptional activation of the human hsp70 gene during infection by DNA viruses. J. Virol. 65:5680-5692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prod'hon, C., I. Machuca, H. Berthomme, A. Epstein, and B. Jacquemont. 1996. Characterization of regulatory functions of the HSV-1 immediate-early protein ICP22. Virology 226:393-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santoro, M. G. 1994. Heat shock proteins and virus replication: hsp70s as mediators of the antiviral effects of prostaglandins. Experientia 50:1039-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sato, B., H. Ito, S. Hinchliffe, M. H. Sommer, L. Zerboni, and A. M. Arvin. 2003. Mutational analysis of open reading frames 62 and 71, encoding the varicella-zoster virus immediate-early transactivating protein, IE62, and effects on replication in vitro and in skin xenografts in the SCID-hu mouse in vivo. J. Virol. 77:5607-5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaack, J., M. L. Bennett, J. D. Colbert, A. V. Torres, G. H. Clayton, D. Ornelles, and J. Moorhead. 2004. E1A and E1B proteins inhibit inflammation induced by adenovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3124-3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiraki, K., and R. W. Hyman. 1987. The immediate early proteins of varicella-zoster virus. Virology 156:423-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang, Q., and G. G. Maul. 2003. Mouse cytomegalovirus immediate-early protein 1 binds with host cell repressors to relieve suppressive effects on viral transcription and replication during lytic infection. J. Virol. 77:1357-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tavaria, M., T. Gabriele, I. Kola, and R. L. Anderson. 1996. A hitchhiker's guide to the human Hsp70 family. Cell Stress Chaperones 1:23-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White, E., D. Spector, and W. Welch. 1988. Differential distribution of the adenovirus E1A proteins and colocalization of E1A with the 70-kilodalton cellular heat shock protein in infected cells. J. Virol. 62:4153-4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuranski, T., H. Nawar, D. Czechowski, J. M. Lynch, A. Arvin, J. Hay, and W. T. Ruyechan. 2005. Cell-type-dependent activation of the cellular EF-1alpha promoter by the varicella-zoster virus IE63 protein. Virology 338:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]