Abstract

Nonstructural protein 4 (nsp4; 204 amino acids) is the chymotrypsin-like serine main proteinase of the arterivirus Equine arteritis virus (order Nidovirales), which controls the maturation of the replicase complex. nsp4 includes a unique C-terminal domain (CTD) connected to the catalytic two-β-barrel structure by the poorly conserved residues 155 and 156. This dipeptide might be part of a hinge region (HR) that facilitates interdomain movements and thereby regulates (in time and space) autoprocessing of replicase polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab at eight sites that are conserved in arteriviruses. To test this hypothesis, we characterized nsp4 proteinase mutants carrying either point mutations in the putative HR domain or a large deletion in the CTD. When tested in a reverse genetics system, three groups of mutants were recognized (wild-type-like, debilitated, and dead), which was in line with the expected impact of mutations on HR flexibility. When tested in a transient expression system, the effects of the mutations on the production and turnover of replicase proteins varied widely. They were cleavage product specific and revealed a pronounced modulating effect of moieties derived from the nsp1-3 region of pp1a. Mutations that were lethal affected the efficiency of polyprotein autoprocessing most strongly. These mutants may be impaired in the accumulation of nsp5-7 and/or suffer from delayed or otherwise perturbed processing at the nsp5/6 and nsp6/7 junctions. On average, the production of nsp7-8 seems to be the most resistant to debilitating nsp4 mutations. Our results further prove that the CTD is essential for a vital nsp4 property other than catalysis.

Proteolytic processing of protein precursors (or polyproteins) is employed to regulate genome expression by many viruses with a single-stranded RNA genome of positive polarity (for reviews, see references 13, 20, 26, and 48). RNA virus polyproteins that include replicative proteins are often processed autocatalytically, although in some virus groups, cellular proteinases are also involved. Such polyproteins may contain up to a dozen identical or highly similar pairs of amino acid residues that are recognized by a viral proteinase. The residues flanking these scissile bonds are commonly referred to as P1 and P1′ (41) and are generally conserved among related viruses. In addition to the structurally uniform P1 and P1′ residues, other residues around the cleavage sites (6, 7, 32), tertiary structure determinants in the substrate, and specific cofactors (15, 39, 52) were implicated in the regulation of autocatalytic processing. As a result, the expression of the replicase gene can be regulated in time and space, e.g., to produce alternative cleavage products or stable processing intermediates with unique functions (10, 23, 30, 55).

Equine arteritis virus (EAV), the prototype of the enveloped positive-strand RNA virus family Arteriviridae in the order Nidovirales, is one of the viruses that employ polyprotein processing to regulate their genome expression. The EAV replicase proteins (nonstructural protein 1 [nsp1] to nsp12 [nsp1-12]) are derived from two large polyproteins, pp1a (1,727 amino acids) and pp1ab (3,175 amino acids); these polyproteins are encoded in the partially overlapping, 5′-proximal open reading frames, ORF1a and ORF1b. pp1a is produced by translation of ORF1a and pp1ab by sequential translation of ORF1a and ORF1b, which involves a ribosomal frameshift occurring just upstream of the ORF1a termination codon (11). These polyproteins have been shown to contain all virus activities essential for genome replication and transcription (33), including a putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (11, 24) and a Zn-binding domain-containing RNA helicase (42, 43). These activities are released from the replicase polyproteins by three virus-encoded proteinases. (In this paper, we use various terms relating to nidovirus proteinases as they were defined by Ziebuhr et al. [58]). Two accessory autoproteinases residing in nsp1 and nsp2 liberate these proteins from the polyprotein (almost) cotranslationally. The nsp4 main proteinase is responsible for the processing of all eight cleavage sites downstream of the nsp2/3 junction. Their Glu/(Ser, Ala, Gly) structure at the P1/P1′ positions, which is conserved in arteriviruses, is typical for sites that are recognized by 3C-like proteinases (46, 58). The critical importance of three nsp4 cleavage sites residing in the ORF1b-encoded part of the EAV replicase polyprotein was previously demonstrated by mutagenesis analysis (51).

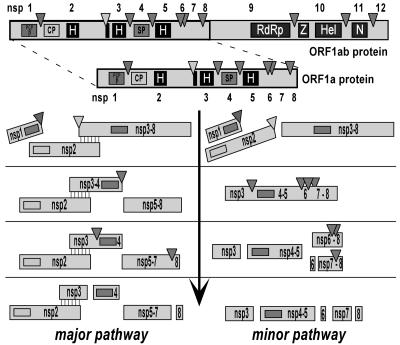

Processing of the C-terminal half of pp1a (nsp3-8) can proceed following either of two alternative proteolytic pathways: the predominantly used major pathway and the secondary minor pathway (52) (Fig. 1). The two pathways differ profoundly with respect to the utilization of the nsp4/5, nsp5/6, and nsp6/7 cleavage sites. In the major pathway, cleavage of the nsp4/5 junction yields nsp3-4 and nsp5-8 processing intermediates. Subsequently, the latter product is cleaved at the nsp7/8 site only, whereas the nsp5/6 and nsp6/7 sites located within the nsp5-7 intermediate appear to remain intact. In the alternative, minor pathway, the nsp4/5 site remains uncleaved, while the nsp5/6 and nsp6/7 sites in the nsp3-8 and nsp4-8 intermediates are processed instead (52).

FIG. 1.

Alternative processing pathways for the EAV replicase pp1a. The figure was modified from references 52 and 58. The three EAV proteinases (PCP1β, CP, and SP) and their cleavage sites are depicted; the EAV nsp nomenclature is used. Prominent hydrophobic domains (H) are indicated. PCP1β, papain-like Cys proteinase; CP, Cys proteinase; SP, nsp4 Ser proteinase, Z, zinc finger; Hel, helicase; N, nidovirus-specific endoribonuclease (NendoU). The association of cleaved nsp2 with nsp3-8 (and probably also nsp3-12) was shown to be a cofactor in the cleavage of the nsp4/5 site by the nsp4 proteinase (major pathway). Alternatively, in the absence of nsp2, the nsp5/6 and nsp6/7 sites are processed and the nsp4/5 junction remains uncleaved (minor pathway). The status of the small nsp6 subunit (fully cleaved or partially associated with nsp5 and/or nsp7) remains to be elucidated.

Thus far, the significance for the viral life cycle of the use of two alternative proteolytic pathways has been understood only poorly. Likewise, the molecular mechanism governing the choice between the two processing pathways remains to be elucidated, although a crucial role was provisionally assigned to nsp2. This protein was shown to be essential for cleavage at the nsp4/5 site of the nsp3-8 intermediate (Fig. 1), implying that it may be a cofactor of the major pathway. Accordingly, support for the existence of a strong interaction between nsp3-8 and nsp2 was derived from the mutual coimmunoprecipitation of the two proteins (52).

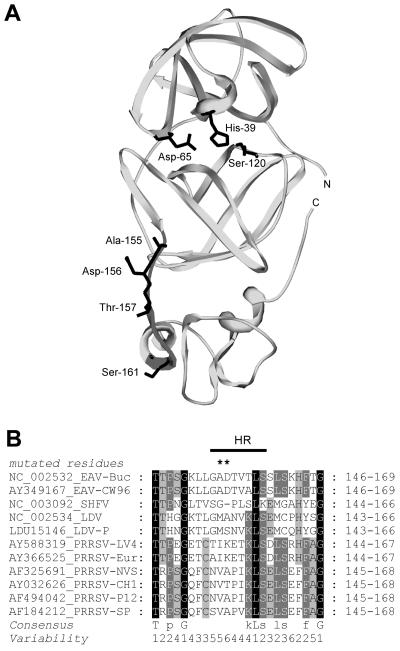

The X-ray crystal structure of the nsp4 proteinase (204 amino acids) has been solved and revealed that the protein folds into a two-β-barrel structure, typical of the catalytic domain of chymotrypsin-like proteinases, which is linked to a structurally unique and functionally uncharacterized C-terminal domain (CTD) of about 45 amino acids (4, 46). The two-β-barrel structure includes a canonical Ser catalytic triad (including His-39/Asp-65/Ser-120) and a substrate-binding pocket similar to those of picornavirus 3C Cys proteinases. (In this paper, unless stated otherwise, all amino acid numbers refer to the nsp4 sequence, which is located between Gly-1065 and Glu-1268 of the EAV replicase polyproteins). In four crystal forms of nsp4 that were described previously, the CTD adopts different orientations relative to the catalytic domain of the proteinase due to the flexibility of the connecting region (amino acids 154 to 161) (Fig. 2A) (4). In this region, either Thr-157 or Ser-161 could act as a hinge to facilitate interdomain movement (4). Accordingly, we will refer to this stretch of amino acids as the hinge region (HR). A similar domain organization was described for the main proteinase of Coronaviridae, another family in the Nidovirales order; this proteinase belongs to the group of 3C-like Cys proteinases (1, 19, 58).

FIG. 2.

(A) Ribbon diagram of the X-ray crystal structure of the EAV nsp4 proteinase. The ribbon diagram was made using DeepView/Swiss-PdbViewer v3.7 (21). Members of the catalytic triad (His-39, Asp-65, and Ser-120) are indicated. Four residues of the hinge region (amino acids 154 to 161) are colored black (see panel B). Residues Thr-157 and Ser-161 may act as a hinge to facilitate the rotation of the C terminus relative to the rest of the proteinase (4). Residues Ala-155 and Asp-156 were targeted for mutagenesis to change the structural flexibility of the nsp4 hinge region. (B) Multiple sequence alignment of the hinge region of main proteinase of arteriviruses. The alignment was generated for a representative set of arteriviruses using the MUSCLE program (14) integrated in the Viralis platform (A. E. Gorbalenya, A. A. Kravchenko, A. M. Leontovich, V. K. Nikolaev, D. V. Samborskiy, and V. A. Sorokin, unpublished). The positions of the N-terminal and C-terminal residues of the alignment are indicated using proteinase numbering. The HR is indicated with a black line. NC_002532_EAV-Buc and AY349167_EAV-CW96, equine arteritis virus strain Bucyrus (11) and CW96 (3), respectively. NC_003092_SHFV, simian hemorrhagic fever virus (56). NC_002534_LDV and LDU15146_LDV-P, lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus neurovirulent type C (18) and strain Plagemann (36), respectively. AY588319_PRRSV-LV4, AY366525_PRRSV-Eur, AF325691_PRRSV-NVS, AY032626_PRRSV-CH1, AF494042_PRRSV-P12, and AF184212_PRRSV-SP signify porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus strain LV4.2.1, strain EuroPRRSV (38), isolate NVSL 97-7985 IA 1-4-2, strain CH-1a, isolate P129, and strain SP (44), respectively.

Determinants that control the relative spatial orientations of the subdomains of nsp4 might be an essential part of a regulatory mechanism that also includes different cleavage sites and cofactors (such as nsp2) and that directs the autoprocessing of EAV replicase polyproteins in time and space. To gain insight into this mechanism, we probed the nsp4 CTD and HR by site-directed mutagenesis. We have analyzed the effect of carefully chosen mutations in vivo by use of an EAV full-length cDNA clone and in a surrogate system by use of transient expression of the full-length ORF1a or its 3′-proximal portion, which encodes nsp4-8. The latter construct allows the selective analysis of the effects that mutations have on the minor processing pathway (52). Three groups of mutations were identified; these produce wild-type (wt)-like, impaired, or dead virus phenotypes and affect replicase polyprotein autoprocessing accordingly in a cleavage-product-specific manner that is modulated by moieties derived from the nsp1-3 region of the replicase polyprotein. A mutated form of nsp4 with a large deletion in the CTD was found to be proteolytically competent, although its ability to cleave cognate sites in pp1a was significantly perturbed. Our data support a modulating role for the CTD in nsp4-mediated autoprocessing of the arterivirus replicase polyproteins and reveal substantial differences in processing efficiency among nsp4 cleavage sites in EAV pp1a.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus, cells, and antisera.

The Bucyrus strain of EAV (5) was grown in baby hamster kidney (BHK-21) cells as described earlier (12). Vaccinia virus recombinant vTF7-3 (17), which produces the T7 RNA polymerase, was propagated in rabbit kidney (RK-13) cells. The anti-nsp4 and anti-nsp7-8 rabbit sera were described previously (as anti-4 M and anti-5, respectively) (47), and the anti-nsp3 serum was described by Pedersen et al. (37). In immunoprecipitation studies, the anti-nsp3 and anti-nsp4 sera were used in a 1:1 mixture.

cDNA constructs.

Mutations were engineered using standard PCR techniques as described by Landt et al. (28). Amplified regions were fully sequenced, and standard recombinant DNA techniques were used (40) to introduce mutations into plasmids pL1a, pL1a3′, and EAV full-length cDNA clone pEAV1a (Table 1). The wt pL1a construct has been described previously in reference 46 and essentially contains the full-length EAV ORF1a (encoding pp1a [nsp1-8]) downstream of a T7 promoter and an encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosomal entry site. pL1a3′ is a similar construct encoding an nsp4-8 polyprotein. It is a modified version of pL(1065-1727) (52), in which the ORF1a/ORF1b ribosomal frameshift site (5′-5399GUUAAAC5405-3′ [11]) in the EAV genome has been inactivated (by mutating it to 5′-5399GUUGAAU5405-3′ [changes are indicated in bold italic type]). Mutated and amplified fragments were introduced in pL1a and pL1a3′ using the unique restriction sites SpeI and EcoRV. pEAV1a is a derivative of EAV full-length cDNA clone pEAV030 (50), which contains a number of translationally silent mutations to engineer restriction sites in ORF1a. As determined in growth curve experiments and plaque assays, virus derived from the pEAV1a clone has a phenotype that was indistinguishable from that of the parental pEAV030-derived virus (data not shown). The HR mutations introduced in pL1a were transferred to pEAV1a via exchange of HindIII-EcoRV restriction fragments.

TABLE 1.

Overview of nsp4 mutants used in this study

| Virus | Sequencea | Amino acid mutation(s) | Phenotypeb |

|---|---|---|---|

| wt | GCC GAC ACC GTG ACT | None | Wild-type |

| N | GCC AAC ACG GTG ACC | D156→N | Wild-type-like |

| G1 | GCC GGC ACC GTG ACT | D156→G | Delayed |

| G2 | GGCGGT ACC GTG ACT | A155→G, D156→G | Delayed |

| G3 | GGCGGCGGT ACC GTG ACT | A155→G, insertion of G, D156→G | Dead |

| P | GCC CCC ACG GTG ACC | D156→P | Dead |

| ΔC | T157-G199 deletion | Dead |

A portion of nsp4 sequence where point mutations were introduced is shown. Mutated codons are underlined. Nucleotide changes are in boldface.

Based on N protein and nsp3 expression after 16, 24, 48 and 72, h p.t. (IFA) and the plaque assays/growth curves illustrated in Fig. 3.

Transient expression and protein analysis.

The EAV nsp1-8 (pp1a) and nsp4-8 polyproteins were transiently expressed in RK-13 cells using the recombinant vaccinia virus/T7 RNA polymerase expression system (17). Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and infected with vaccinia virus recombinant vTF7-3 in serum-free medium (multiplicity of infection of 10). After 1 h at 37°C, the inoculum was removed and cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline. Transfection of 5 × 105 cells in a 3.5-cm2 dish was mediated by cationic liposomes (Lipofectamine Plus; Invitrogen) using 750 ng of plasmid DNA, 2 μl of Plus reagent, and 8 μl of Lipofectamine reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol. Proteins synthesized in transfected cells were labeled with 200 μCi/ml 35S-Promix (Amersham) from 5 to 10 h after vaccinia virus infection. Protocols for cell lysis and immunoprecipitation have been described previously (47). Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) according to the method of Laemmli (27), and the amount of 35S label incorporated into protein bands was measured using a phosphorimager (Bio-Rad molecular imager FX) and quantified using Bio-Rad Quantity One software.

EAV reverse genetics.

The methods used for transcription of EAV full-length cDNA clones to produce infectious RNA and for RNA transfection of BHK-21 cells by electroporation have been described previously (50). RNA quality and yield were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Virus replication in transfected cells and transfection efficiency were assayed by indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFA) (49) using rabbit antiserum directed against replicase subunit nsp3 and the nucleocapsid (N) protein. Plaque assays were carried out according to previously described protocols (45).

RESULTS

Rationale for EAV nsp4 mutagenesis and experimental setup.

To gain insight into the function of nsp4, we characterized six mutants in which the HR and CTD were targeted (Table 1). Since the N-terminal region of the HR includes residues that are not well conserved among arteriviruses (Fig. 2B), one might expect that EAV would tolerate a broad range of artificial mutations in this region. If, on the other hand, the HR does play the role postulated in the Introduction, EAV should poorly tolerate mutations that are likely to severely affect HR flexibility. Therefore, we chose to mutate the HR by introducing Gly and Pro residues, which are known for their extreme effects on the conformational flexibility of polypeptide chains (9, 16, 22, 25, 35, 53). We targeted residues Ala-155 and/or Asp-156, which together with Gly-154 form the most variable stretch in this region and immediately precede Thr-157, a predicted hinge residue (Fig. 2). To gradually increase the effect of these mutations, three HR mutants carrying one, two, or three foreign Gly residues that were introduced through replacement and/or insertion were generated (mutants G1, G2, and G3, respectively) (Table 1). Two other mutants in which Asp-156 was replaced with either Pro (P) (with an expected strong effect on the flexibility) or Asn (N) (as a plausible negative control) were also characterized. To determine whether the CTD is required for nsp4 proteolytic activity, a ΔC deletion mutant was engineered. In this mutant, the entire CTD was deleted with the exception of the six most C-terminal residues, occupying positions P6 to P1 of the nsp4/5 cleavage site. This site was expected to remain functional, since a peptide including the P6-to-P1 region was previously shown to be a minimal substrate for a picornavirus 3C proteinase (8).

The phenotypic consequences of the nsp4 mutations were characterized by analysis of the accumulation of selected autoprocessing products, virus infectivity, and plaque morphology following transfection of infectious EAV RNA into BHK-21 cells or by use of the recombinant vaccinia virus/T7 RNA polymerase expression system (see Materials and Methods).

Differential effects of nsp4 mutations on EAV phenotype are compatible with the postulated role of the HR domain.

For an in vivo analysis, each of the six mutations was separately transferred to an EAV full-length cDNA clone. The initial screening of mutant viruses was done on the basis of a double IFA for replicase subunit nsp3 and the N protein, which are indicative of the synthesis of genome and subgenomic mRNA7, respectively (45). Mutant viruses were characterized at different time points posttransfection (p.t.). In repeated experiments, three nsp4 mutants (N, G1, and G2) proved to be IFA positive, while three others (G3, P, and ΔC) were not (data not shown). The N mutant was virtually indistinguishable from the parental virus; both had spread efficiently to initially untransfected cells by 24 h p.t. In contrast, the development of the IFA signals of mutants G1 and G2 was delayed, an effect that was most pronounced for G1. For both these mutants, infection of the entire cell monolayer was observed only at 48 h p.t.

To analyze the effects of the mutations in more detail, virus progenies of the G1 and G2 mutants in the transfected cell culture supernatants were further quantified by plaque assays at 14, 23, 32, 38, and 45 h p.t. (Fig. 3B). It was found that G2 and, in particular, G1 had lower titers than the wt control and that even at 45 h p.t. both mutants failed to reach the titers obtained for wt virus (around 108 PFU/ml). The reduced virus production was also reflected in a smaller plaque size (Fig. 3A). These results were in agreement with the IFA data and confirmed the delayed phenotype of the G1 and G2 mutants. A reverse transcription-PCR and sequence analysis of viral RNA isolated from cells infected with the 48-h-p.t. supernatant confirmed the presence of the original G1 and G2 mutations in the nsp4-encoding region (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

(A) Plaque assay of wild-type control virus EAV1a and nsp4 mutants EAV1a-G1 and EAV1a-G2. BHK-21 cells were transfected with in vitro-transcribed infectious (wt or mutant) RNA. The representative plaque morphology obtained with progeny virus harvested at 48 h p.t. is shown. (B) Virus growth curves. BHK-21 cells were transfected with infectious RNA generated from wt (pEAV1a) and mutant (pEAV1a-G1 or -G2) full-length cDNA clones. Samples of the transfected cell culture supernatants were taken at 14, 23, 32, 38, and 45 h p.t. and subjected to virus titration as described in Materials and Methods.

In conclusion, the nsp4 mutants showed diverse in vivo phenotypes that could be placed in three groups: wt-like (N), crippled (G1 and G2), and dead (G3, P, and ΔC). The above grouping seems sensible, as the mutations underlying these phenotypes may be similarly grouped on the basis of their expected impact on nsp4 function, as predicted from the structural considerations explained above. Thus, the results supported the postulated role of the HR domain in nsp4 function and justified further analysis of the mutations.

The nsp4 mutations have diverse effects on pp1a autoprocessing, which correlate with the in vivo phenotypes.

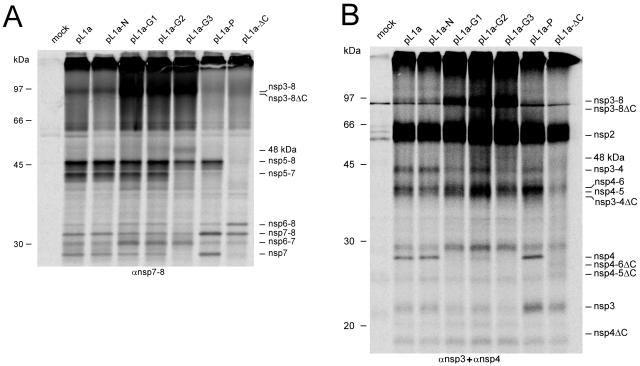

Since the lethal and crippling nsp4 mutations either blocked or severely impaired virus replication, further characterization of the mutations on EAV replicase polyprotein processing was not feasible in the EAV reverse genetics system. Therefore, the recombinant vaccinia virus/T7 RNA polymerase expression system was used to express wt and mutant full-length pp1a from pL1a. 35S-labeled pp1a processing products were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. To enhance the detection of the minor pathway products, which are hardly visible otherwise, cells were labeled for 5 h (between 5 and 10 h after vaccinia virus infection, instead of the 3-h labeling period [5 to 8 h postinfection] used in other studies). The typical processing patterns of wt EAV pp1a, described in detail before (47, 52), and of the nsp4 mutants are shown in Fig. 4.

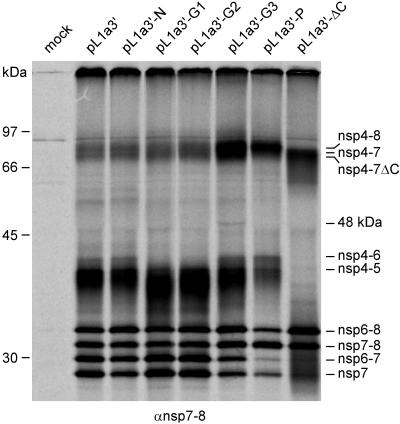

FIG. 4.

Expression and processing of the full-length EAV pp1a using the recombinant vaccinia virus/T7 RNA polymerase expression system (see Materials and Methods). Immunoprecipitation analysis of the pL1a-ΔC mutant and the pL1a HR mutants after a 5-h labeling interval by use of an anti-nsp7-8 serum (panel A) and a mixture of anti-nsp3 and anti-nsp4 sera (panel B). Because nsp2 is present in this system, pp1a processing occurs mainly via the major pathway (in which the nsp5/6 and nsp6/7 sites are not cleaved), although small amounts of the products of the minor pathway (no cleavage of the nsp4/5 site, but cleavage of the nsp5/6 and nsp6/7 sites instead) can also be detected. Mock-transfected cells, wt pL1a, and the pL1a-N control mutant were included as controls. nsp2 is coprecipitated due to complex formation with nsp3 and/or nsp3-containing processing intermediates. The positions of the molecular mass markers used during SDS-PAGE and the various processing products are indicated.

As expected, the characterization of the wt-like N mutant using the anti-nsp3, anti-nsp4, and anti-nsp7-8 sera revealed no effect of the mutation on the pp1a processing profile (Fig. 4). The other mutants, however, displayed moderate to severe changes in pp1a processing.

The crippled mutants G1 and G2 displayed a significantly increased accumulation of the nsp3-8 precursor (Fig. 4) and a somewhat increased level of nsp6-8 and nsp6-7 in comparison with the wt control (Fig. 4A). By use of the nsp3 and nsp4 antisera (Fig. 4B), some fully processed nsp4 was observed for the G2 but not for the G1 mutant. The latter mutant also displayed only trace amounts of nsp3 and nsp3-4, whereas the G2 mutant was comparable to the wt control in this respect.

As a group, the three mutations that were lethal in the reverse genetics system (G3, P, and ΔC) induced the processing profiles that most strongly deviated from that of wt pp1a and did not show the accumulation of nsp5-7, which was evident as a prominent band by use of constructs that represented the four viable viruses (Fig. 4A). In other respects, these profiles were mostly mutant specific, as described below.

G3 was somewhat similar to the crippled G1 and G2 mutants in terms of the altered relative abundances of the nsp3-8, nsp7-8, and nsp6-7 intermediates. It accumulated virtually no nsp4 and significantly less nsp3-4 (Fig. 4B). Compared with its wt parent, G3 accumulated very small (or no) amounts of nsp7 and nsp5-7 and, in comparison to mutants G1 and G2, showed a pronounced decrease in the quantities of nsp5-8 and nsp6-8. This mutant also generated a minor 48-kDa product, the origin of which remains to be established (Fig. 4A).

In the case of the P mutant, the processing deviations included the accumulation of large amounts of nsp7-8 and nsp7 and small amounts of nsp5-7 and nsp3-8. Among all characterized pp1a variants, including the wt control, this mutant accumulated nsp4 and nsp3 most efficiently (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the accumulation of nsp6-7 and nsp6-8 seemed to be least affected by the mutation (Fig. 4B).

The ΔC mutation caused the most dramatic effects on replicase processing (the rightmost lane in Fig. 4A and B). Compared to what was seen in the wt pp1a processing profile, the production of nsp7-8 and nsp6-7 seemed to be least affected, while amounts of nsp6-8 increased and nsp7 decreased markedly (Fig. 4A). Other processing intermediates (nsp3-8, nsp5-8, and nsp5-7) were present in trace amounts at best. Hardly any nsp4-ΔC or potential precursors thereof were detected at the expected positions in the gel (Fig. 4B), although the nsp4 antibody (raised against residues 113 to 129, which are located upstream of the ΔC deletion) was able to recognize nsp4-ΔC and nsp4-ΔC-containing precursor proteins in a separate set of experiments that used a different expression construct (data not shown). In contrast, much larger amounts of nsp3 were immunoprecipitated for this mutant than for the wt control (Fig. 4B).

Taken together, these data reveal that nsp4 proteolytic activity and pp1a processing are variably affected by the mutations tested. A broad range of effects was observed, although none of the mutations, including ΔC, inactivated the enzyme. Overall, the results correlated well with the in vivo phenotypes of the corresponding mutant viruses. The best correlation was evident between the virus phenotype and the transient expression results obtained using the anti-nsp7-8 serum (compare Fig. 3 and 4A).

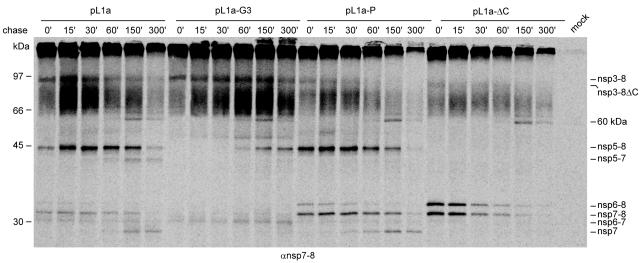

Pulse-chase analysis of pp1a autoprocessing reveals specific defects induced by lethal nsp4 mutations.

From the experiments presented in Fig. 4, which utilized 5 h of continuous labeling, it was not possible to deduce whether the absence of a protein was due to its increased turnover or due to its diminished production. To address this dilemma, the autoprocessing activities of the pp1a mutants with the most serious processing defects (see data for ΔC, G3, and P mutants in Fig. 4 and text above) as well as that of wt pp1a were compared in a pulse-chase experiment. Transfected cells were pulse-labeled for 15 min and chased for five different intervals of up to 300 min. The processing products were immunoprecipitated with the anti-nsp7-8 serum (Fig. 5; also see Materials and Methods). Although not truly quantitative, this experiment provided a first window on the kinetics of the accumulation of nsp7-8-related processing products for these nsp4 mutants and their parent.

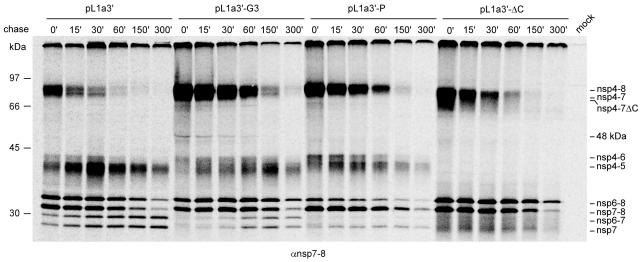

FIG. 5.

Pulse-chase experiment to analyze the in vitro processing of wt full-length EAV pp1a and mutants G3, P, and ΔC. Proteins were 35S labeled for 15 min, chased up to 300 min, and then immunoprecipitated with an anti-nsp7-8 serum. nsp4-5 and nsp4-6 are presumably coimmunoprecipitated by an unknown interaction with the precursor or other products brought down by the anti-nsp7-8 serum. For more information, see also the legend for Fig. 4.

Upon processing of the wt pp1a, early products that could be detected immediately after the 15-min pulse were nsp3-8, nsp5-8, nsp6-8, nsp7-8, and nsp6-7 (Fig. 5, pL1a lane). After the 15-min chase, the sharp increase of the amounts of nsp3-8 and nsp5-8, which became the most abundant proteins, was striking. Following the 300-min chase, these and three other initially labeled proteins were down to or below prechase levels. In contrast, nsp5-7, nsp7, and an ∼60-kDa band were first detected after chase times of 60 to 150 min. These proteins, along with nsp5-8, were most abundant by the 300-min chase, when the total amount of labeled proteins was less than that detected after the initial pulse.

In the nsp4 mutants, the pulse-chase kinetics were mutant specific and compatible with the profiles that were observed upon continuous labeling (Fig. 4A). It is most informative to compare the pulse-chase kinetics of the mutants to that of the wt pL1a construct. Apparently, the only common feature shared by mutants and the wt control is an ∼60-kDa band, the intensity of which steadily increased between 60 and 150 min of chase time and faded away by the 300-min chase time point. This band may be of cellular origin, since none of the already described virus proteins derived from the nsp7 region of pp1a would be compatible with its migration and chase kinetics.

Compared to the wt control, the G3 mutant showed less diversity of labeled bands and a decreased processing efficiency after the initial pulse (Fig. 5). During the chase, redistribution of the label from the larger intermediates, including the most abundant, nsp3-8, along with nsp5-8 and nsp5-7 (which was visible for the G3 mutant only after a prolonged exposure), to smaller processing products (nsp6-8, nsp7-8, and nsp7) was less efficient and significantly delayed, peaking only after the 150-min chase. The only exception to this trend was the more efficient albeit slower accumulation of nsp6-7 observed for the G3 mutant.

In contrast, when comparing the nsp4 mutants, the overall pulse-chase processing kinetics of the P mutant resembled that of the parental construct most closely (Fig. 5), with the major difference being the generally increased processing efficiency of the P mutant. In particular, the relative amounts of the nsp3-8 and nsp5-8 intermediates were decreased at all time points and at the three last time points of chase, respectively. Accordingly, nsp5-8 steadily accumulated after the initial pulse and 15 to 30 min of chase, and a relative increase in the accumulation of the smaller products nsp6-8, nsp7-8, and, to a lesser extent, nsp7 was also observed at all time points. The absence of nsp5-7 in the assay for the P mutant was most striking.

The most distinct differences in pp1a processing kinetics were observed for the ΔC mutant (Fig. 5). No nsp7 and only trace amounts of nsp6-7 and nsp3-8ΔC could be detected after the pulse and during the chase. nsp6-8 and nsp7-8 were unusually prominent after the initial pulse and gradually disappeared during the chase.

In conclusion, the analysis of the pulse-chase kinetics of nsp7-related proteins shows that the three nsp4 mutations that are lethal in the reverse genetics system affect pp1a autoprocessing in a mutation-specific manner. The processing efficiency is either inhibited (G3) or stimulated (P), or the diversity of cleavage products is substantially reduced (ΔC). Despite these differences, and in line with the results of the continuous-labeling experiment (Fig. 4), polyproteins carrying these mutations showed little if any production of nsp5-7, which, in contrast, was steadily accumulated upon expression of wt pp1a (Fig. 4A and 5).

Minor pathway analysis using an nsp4-8 polyprotein: effects of nonlethal nsp4 mutations.

We further compared the mutants by use of a smaller construct (pL1a3′) which encodes an nsp4-8 polyprotein. This polypeptide was previously shown to be processed exclusively through the minor pathway, with the lack of cleavage at the nsp4/5 site being the most prominent difference with full-length pp1a processing (52). The analysis of the pL1a3′ series was conducted using the same expression protocol used for the pL1a constructs (Fig. 4 and 5; also see the text above). Proteins either were continuously labeled for 5 h or were pulse-labeled for 15 min with subsequent chase times up to 300 min before they were immunoprecipitated with the nsp7-8 antiserum (Fig. 6 and 7). Compared to the processing of wt pp1a, that of wt nsp4-8 was significantly more efficient, as the label accumulated predominantly in processing end products, such as nsp6-8, nsp7-8, nsp6-7, and nsp7. Also, the amount of label remaining near the top of the gel was greatly diminished (compare Fig. 4A and 6). The wt-like N mutant and the crippled G1 and G2 mutants did not display major processing differences when compared to each other or the wt control, except for some minor variations in the ratio between nsp6-8, nsp7-8, nsp6-7, and nsp7. For the G1 and G2 mutants, no detectable amounts of nsp4-6 were coprecipitated.

FIG. 6.

Expression and processing of the EAV nsp4-8 polyprotein using the recombinant vaccinia virus/T7 RNA polymerase expression system (see Materials and Methods). The nsp4-8 polyprotein is processed via the minor pathway exclusively. In the absence of nsp2, the nsp4 proteinase is unable to process the nsp4/5 junction, but the other cleavage sites can be processed (52). nsp4-5 and nsp4-6 are presumably coimmunoprecipitated due to an uncharacterized interaction with nsp7- and/or nsp8-containing polypeptides. Wild-type pL1a3′, pL1a3′-N, and mock-transfected cells were included as controls. The positions of the molecular mass markers used during SDS-PAGE and the various processing products are indicated.

FIG. 7.

Pulse-chase experiment to analyze the in vitro processing of the wt EAV nsp4-8 polyprotein and mutants G3, P, and ΔC. Proteins were 35S labeled for 15 min, chased up to 300 min, and then immunoprecipitated with an anti-nsp7-8 serum. For more information, see also the legend for Fig. 6.

The enhanced efficiency of nsp4-8 autoprocessing, compared to that of full-length pp1a, is also evident upon analysis of the pulse-chase results. Figure 7 (panel pL1a3′) illustrates that, directly after the 15-min pulse, nsp4-8, nsp4-7, nsp6-8, and nsp7-8 were abundantly present and that these products gradually diminished with species-specific kinetics during the chase. Accordingly, nsp6-7 and nsp7 gradually accumulated during the chase and are believed not to be subject to further processing (46). Although an antibody against nsp7-8 was used, nsp4-5 and nsp4-6 were coimmunoprecipitated due to an as-yet-undefined interaction with one of the other processing products. The amounts of these proteins peaked after the 30-min chase, indicating that they are processing intermediates and partially stable. The pulse-chase kinetics of mutants N, G1, and G2 were highly similar to that of the wt control (data not shown), in agreement with the results of the 5-h continuous-labeling experiment (Fig. 6).

These results show that the processing of nsp4-8 polyproteins carrying nsp4 mutations that are tolerated, to a certain extent, by EAV (Fig. 3) correlated with that of the full-length pp1a. As expected, the generation of the four nsp7-containing minor pathway products with sizes around ∼30 kDa was highly efficient upon autoprocessing of the nsp4-8 polyprotein.

Minor pathway analysis using an nsp4-8 polyprotein: significant effect of lethal nsp4 mutations.

Compared to the wt parental construct, the G3 mutation exerted relatively minor effects on the accumulation of and ratio between nsp6-8, nsp7-8, nsp6-7, and nsp7. In contrast, the G3 mutation induced a significant accumulation of nsp4-8 and nsp4-7 (Fig. 6). These observations were corroborated by the results of a pulse-chase analysis (Fig. 7): in comparison with the wt control, the G3 mutant displayed a much slower turnover of nsp4-8, nsp4-7, nsp6-8, and nsp7-8 as well as a reduced accumulation of nsp6-7 and nsp7. These results were consistent with the data obtained using full-length pp1a (Fig. 5).

The nsp4-8 precursor of the P mutant and the nsp4-8ΔC derivative of the ΔC mutant were processed less efficiently than their wt counterparts (Fig. 6 and 7). These results were in contrast to those observed in the pp1a analysis (Fig. 4A and 5), where these mutants, unlike the wt control and Gly mutants, did not show a significant accumulation of nsp3-8 (nsp3-8ΔC), the largest intermediate of similar size. For the P and ΔC mutants, the accumulation and ratio of the four nsp7-containing bands migrating around ∼30 kDa were significantly affected in a mutation-specific manner. Compared to the wt control, mutants P and ΔC produced less and more nsp6-8, respectively. In contrast, nsp7-8 production and nsp6-8/nsp7-8 turnover were not significantly affected in either of these mutants. In the ΔC lane of the gel, the nsp6-7 and nsp7 proteins were obscured by fuzzy bands, most likely representing coimmunoprecipitated nsp4-5ΔC and nsp4-6ΔC, which are expected to migrate faster than their counterparts from the wt control (Fig. 6). Despite this technical complication, it is apparent that the ΔC and P mutations impaired the production of nsp7 and, more significantly, of nsp6-7 (Fig. 6 and 7).

In conclusion, the three nsp4 mutations that were lethal in the reverse genetics system induced significantly slower processing of nsp4-8, a defect that was not observed for the mutations that resulted in viable virus mutants. The effects of these mutations were also evident at the level of production and turnover of nsp6-8, nsp7-8, nsp6-7, and nsp7, most significantly for the P and ΔC mutants. Some of these effects were not detected upon analysis of full-length pp1a processing, indicating that moieties derived from the nsp1-3 region modulate nsp4-mediated processing at the more distal pp1a cleavage sites.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we describe the characterization of EAV nsp4 proteinase mutants carrying either point mutations in the putative HR domain or a large deletion in the CTD (Table 1; Fig. 2). These mutations compromised the proteolytic autoprocessing of EAV pp1a in both mutation- and cleavage-product-specific manners, effects that were also modulated by moieties derived from the nsp1-3 region of pp1a. Mutations that were predicted to affect the flexibility of the HR most strongly, as well as the CTD deletion, caused the most serious processing abnormalities, and they accordingly were found to be lethal for EAV upon in vivo analysis by reverse genetics. These mutants may be impaired in the accumulation of nsp5-7 through the major pathway and/or suffer from delayed or otherwise perturbed minor pathway processing. On average, when tested in the transient expression system, the production of nsp7-8 seems to be most resistant to debilitating nsp4 mutations. Our results further prove that the CTD is essential for a vital nsp4 property other than catalysis.

The replication of arteriviruses involves the production of a set of diverse virus-specific RNAs of both polarities that differ in size, role, and, likely, kinetics of accumulation. These RNAs are synthesized by a barely characterized replication/transcription complex, the core components of which are derived from the replicase polyproteins by an autoprocessing cascade in which nsp4 plays a major role. An intimate link between the intricacies of replicase processing and the progression of the viral life cycle was previously revealed for Sindbis virus and poliovirus, which belong to the Togaviridae and Picornaviridae families, respectively (29, 30). For instance, in poliovirus, the 3D RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) moiety directs the 3C-mediated proteinase activity of the 3CD intermediate in cleaving the capsid precursor, while individual 3C predominantly cleaves the replicase precursor (23, 55).

The multidomain organization of arterivirus nsp4 is somewhat reminiscent of that of poliovirus 3CD in that both enzymes are composed of a chymotrypsin-like proteinase domain fused to a C-terminal domain, although those domains of arteriviruses and poliovirus are unrelated. This parallel is further strengthened by observations that both proteinases have similar substrate specificities and cleave sites that are flanked by identical (3C/3CD) or highly similar (nsp4) dipeptides. The EAV nsp4 crystal structure revealed that, due to HR flexibility, the CTD is able to adopt different orientations relative to the two-β-barrel proteinase core, suggesting that this domain may have a modulating, HR-dependent role in nsp4 function (4).

Our experiments now show that, in line with this model, EAV nsp4 is sensitive to HR mutations to an extent that is proportional to the expected interference of mutations with HR flexibility. The phenotypes of the nsp4 mutant viruses ranged from wt-like (N) via impaired (G1 and G2) to dead (G3, P, and ΔC). These findings further indicate that EAV viability may be critically compromised even by a point mutation introduced in a relatively rapidly evolving region (Fig. 2B).

To gain insight into the mechanism by which the HR may modulate EAV nsp4 function, we characterized replicase polyprotein autoprocessing for the five HR mutants and the CTD deletion mutant. Since five out of the six mutants were either dead (G3, P, and ΔC) or crippled (G1 and G2), we employed the recombinant vaccinia virus/T7 RNA polymerase expression system, which previously proved to be a powerful system for studying pp1a processing (46, 52). The positive correlation observed in this study between the effects of the nsp4 mutations on virus viability and nsp4-8 autoproteolysis in the expression system further validates the latter assay, which even proved to be sensitive enough to discriminate between the G1 and G2 mutants, which were phenotypically very close (Fig. 3). The analysis of pp1a autoprocessing with the anti-nsp7-8 antiserum proved to be the most accurate and sensitive surrogate system for discriminating between dead and viable nsp4 mutants.

Analysis of mutants G1 and G2 uncovered, on one hand, that EAV is capable of tolerating some variations in pp1a processing and, on the other hand, that replicase proteolysis is likely to be fine-tuned to achieve maximal progeny production. The latter conclusion is also supported by the observation that a mutation (Asp-156 to Pro) inducing enhanced polyprotein proteolysis in the expression system was lethal in the reverse genetics system. In line with the previous observations that nsp2 interacts with nsp3 (and nsp3-containing proteins) and could be a cofactor of nsp4-mediated cleavage (52), we observed that the effects of the nsp4 mutations on nsp4-8 processing were strongly modulated in the presence of moieties derived from the nsp1-3 region.

Somewhat surprisingly, the ΔC mutant proved to be proteolytically competent, with its activity being comparable to that of wt proteinase with respect to replicase polyprotein processing at some sites. This finding sharply contrasts with the reported major reduction or block of proteolytic activity for C-terminally truncated mutants of the main proteinase (a 3C-like Cys proteinase) of the distantly related coronaviruses (1, 31, 34, 57). The observed difference could be of a technical nature, as the roles of the CTD in coronavirus and arterivirus main proteinases were analyzed using different assays. Alternatively, the respective CTDs, which are structurally different, may play different roles (1, 2, 4, 54, 58). One of the proposed main functions of the coronavirus CTD (domain III) was to keep the interdomain II and III loop in the conformation that this essential for catalysis (1), a property that was not evident from the structure of the EAV nsp4 (4). It could be revealing to compare the phenotypes of coronavirus main proteinase mutants similar to those described for EAV in this report.

The three dead mutants showed also the most serious, albeit remarkably diverse, deviations in nsp4-mediated polyprotein autoprocessing, which least affected the accumulation of nsp7-8. Most consistently, an (almost) complete block was observed for the accumulation of nsp5-7, a key product of the major pp1a processing pathway. Its production, which involves cleavage of the nsp7/8 junction, might be coupled with that of the adjacent RdRp-containing nsp9 subunit from the pp1ab polyprotein, since release of the N terminus of nsp9 also requires processing of the nsp7/8 site (Fig. 1). Either the production or the turnover of the nsp5-7 protein may have been dramatically affected in the case of the dead mutants. For example, this protein would not be produced if the cleavage at the nsp4/5 or nsp7/8 junctions was blocked in its precursor(s), an interpretation that seems most plausible for the ΔC mutant, in which the CTD deletion ends just 6 amino acids upstream of the nsp4/5 site. In an alternative scenario, the turnover of nsp5-7 could be significantly accelerated provided that the lethal mutations trigger the processing of an internal site(s) within nsp5-7, which has thus far been considered an end product of the major processing pathway in infected cells (47). Mechanistically, these mutations may have affected either nsp4 or its substrates or both, and further studies, also involving trans-cleavage assays, need to resolve this aspect.

In conclusion, we provide evidence for a vital modulating role of the CTD in the nsp4-mediated processing of the EAV replicase polyproteins (46, 47, 51, 52). CTD function may be controlled by the flexible and relatively rapidly evolving HR. Our results further prove that EAV has evolved the capacity to differentially process the uniform nsp4 cleavage sites in its replicase polyproteins through an interplay between the proteinase, cofactor(s), and substrate proteins. The mutants characterized in this study, which represent a broad range of phenotypes, will be useful in the further elucidation of the maturation and function of the EAV replicase complex.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessika Zevenhoven-Dobbe for technical assistance; Isabelle H. Barrette-Ng and Kenneth K.-S. Ng for help with the interpretation of the nsp4 structure; Alexander Kravchenko, Andrey Leontovich, Valery Sorokin, Vladimir Nikolaev, and Dmitry Samborskiy for the Viralis development; and Willy Spaan and Fred Wassenaar for helpful discussions and support.

D.V.A. was supported by a grant from the Leiden University Stimuleringsfonds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anand, K., G. J. Palm, J. R. Mesters, S. G. Siddell, J. Ziebuhr, and R. Hilgenfeld. 2002. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra alpha-helical domain. EMBO J. 21:3213-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand, K., J. Ziebuhr, P. Wadhwani, J. R. Mesters, and R. Hilgenfeld. 2003. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science 300:1763-1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balasuriya, U. B., J. F. Hedges, V. L. Smalley, A. Navarrette, W. H. McCollum, P. J. Timoney, E. J. Snijder, and N. J. MacLachlan. 2004. Genetic characterization of equine arteritis virus during persistent infection of stallions. J. Gen. Virol. 85:379-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrette-Ng, I. H., K. K. S. Ng, B. L. Mark, D. van Aken, M. M. Cherney, C. Garen, Y. Kolodenko, A. E. Gorbalenya, E. J. Snijder, and M. N. G. James. 2002. Structure of arterivirus nsp4—the smallest chymotrypsin-like proteinase with an alpha/beta C-terminal extension and alternate conformations of the oxyanion hole. J. Biol. Chem. 277:39960-39966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryans, J. T., E. R. Doll, and R. E. Knappenberger. 1957. An outbreak of abortion caused by the equine arteritis virus. Cornell Vet. 47:69-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao, X., and E. Wimmer. 1996. Genetic variation of the poliovirus genome with two VPg coding units. EMBO J. 15:23-33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charini, W. A., S. Todd, G. A. Gutman, and B. L. Semler. 1994. Transduction of a human RNA sequence by poliovirus. J. Virol. 68:6547-6552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordingley, M. G., P. L. Callahan, V. V. Sardana, V. M. Garsky, and R. J. Colonno. 1990. Substrate requirements of human rhinovirus 3C protease for peptide cleavage in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 265:9062-9065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creighton, T. E. 1993. Proteins. Structures and molecular properties. W. H. Freeman & Co., New York, N.Y.

- 10.de Groot, R. J., W. R. Hardy, Y. Shirako, and J. H. Strauss. 1990. Cleavage-site preferences of Sindbis virus polyproteins containing the non-structural proteinase. Evidence for temporal regulation of polyprotein processing in vivo. EMBO J. 9:2631-2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Boon, J. A., E. J. Snijder, E. D. Chirnside, A. A. De Vries, M. C. Horzinek, and W. J. Spaan. 1991. Equine arteritis virus is not a togavirus but belongs to the coronaviruslike superfamily. J. Virol. 65:2910-2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vries, A. A., E. D. Chirnside, M. C. Horzinek, and P. J. Rottier. 1992. Structural proteins of equine arteritis virus. J. Virol. 66:6294-6303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dougherty, W. G., and B. L. Semler. 1993. Expression of virus-encoded proteinases: functional and structural similarities with cellular enzymes. Microbiol. Rev. 57:781-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edgar, R. C. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792-1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Failla, C., L. Tomei, and R. De Francesco. 1994. Both NS3 and NS4A are required for proteolytic processing of hepatitis C virus nonstructural proteins. J. Virol. 68:3753-3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiorani, P., A. Bruselles, M. Falconi, G. Chillemi, A. Desideri, and P. Benedetti. 2003. Single mutation in the linker domain confers protein flexibility and camptothecin resistance to human topoisomerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 278:43268-43275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuerst, T. R., E. G. Niles, F. W. Studier, and B. Moss. 1986. Eukaryotic transient-expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:8122-8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godeny, E. K., L. Chen, S. N. Kumar, S. L. Methven, E. V. Koonin, and M. A. Brinton. 1993. Complete genomic sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV). Virology 194:585-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorbalenya, A. E., E. V. Koonin, A. P. Donchenko, and V. M. Blinov. 1989. Coronavirus genome: prediction of putative functional domains in the non-structural polyprotein by comparative amino acid sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:4847-4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorbalenya, A. E., and E. J. Snijder. 1996. Viral cysteine proteases. Perspect. Drug Discov. Design 6:64-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guex, N., and M. C. Peitsch. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18:2714-2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofmann, M. W., K. Weise, J. Ollesch, P. Agrawal, H. Stalz, W. Stelzer, F. Hulsbergen, H. de Groot, K. Gerwert, J. Reed, and D. Langosch. 2004. De novo design of conformationally flexible transmembrane peptides driving membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:14776-14781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jore, J., B. De Geus, R. J. Jackson, P. H. Pouwels, and B. E. Enger-Valk. 1988. Poliovirus protein 3CD is the active protease for processing of the precursor protein P1 in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 69:1627-1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamer, G., and P. Argos. 1984. Primary structural comparison of RNA-dependent polymerases from plant, animal and bacterial viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:7269-7282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim, J. M., P. J. Booth, S. J. Allen, and H. G. Khorana. 2001. Structure and function in bacteriorhodopsin: the role of the interhelical loops in the folding and stability of bacteriorhodopsin. J. Mol. Biol. 308:409-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krausslich, H. G., and E. Wimmer. 1988. Viral proteinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 57:701-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landt, O., H.-P. Grunert, and U. Hahn. 1990. A general method for rapid site-directed mutagenesis using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 96:125-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawson, M. A., and B. L. Semler. 1992. Alternate poliovirus nonstructural protein processing cascades generated by primary sites of 3C proteinase cleavage. Virology 191:309-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemm, J. A., T. Rumenapf, E. G. Strauss, J. H. Strauss, and C. M. Rice. 1994. Polypeptide requirements for assembly of functional Sindbis virus replication complexes: a model for the temporal regulation of minus- and plus-strand RNA synthesis. EMBO J. 13:2925-2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu, Y., and M. R. Denison. 1997. Determinants of mouse hepatitis virus 3C-like proteinase activity. Virology 230:335-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merits, A., L. Vasiljeva, T. Ahola, L. Kaariainen, and P. Auvinen. 2001. Proteolytic processing of Semliki Forest virus-specific non-structural polyprotein by nsP2 protease. J. Gen. Virol. 82:765-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molenkamp, R., H. van Tol, B. C. Rozier, Y. van der Meer, W. J. Spaan, and E. J. Snijder. 2000. The arterivirus replicase is the only viral protein required for genome replication and subgenomic mRNA transcription. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2491-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng, L. F., H. Y. Xu, and D. X. Liu. 2001. Further identification and characterization of products processed from the coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) 1a polyprotein by the 3C-like proteinase. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 494:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okoniewska, M., T. Tanaka, and R. Y. Yada. 2000. The pepsin residue glycine-76 contributes to active-site loop flexibility and participates in catalysis. Biochem. J. 349:169-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmer, G. A., L. Kuo, Z. Chen, K. S. Faaberg, and P. G. W. Plagemann. 1995. Sequence of the genome of lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus: heterogenicity between strains P and C. Virology 209:637-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedersen, K. W., Y. van der Meer, N. Roos, and E. J. Snijder. 1999. Open reading frame 1a-encoded subunits of the arterivirus replicase induce endoplasmic reticulum-derived double-membrane vesicles which carry the viral replication complex. J. Virol. 73:2016-2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ropp, S. L., C. E. Wees, Y. Fang, E. A. Nelson, K. D. Rossow, M. Bien, B. Arndt, S. Preszler, P. Steen, J. Christopher-Hennings, J. E. Collins, D. A. Benfield, and K. S. Faaberg. 2004. Characterization of emerging European-like porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates in the United States. J. Virol. 78:3684-3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rott, M. E., A. Gilchrist, L. Lee, and D. Rochon. 1995. Nucleotide sequence of tomato ringspot virus RNA1. J. Gen. Virol. 76:465-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 41.Schechter, I., and A. Berger. 1967. On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 27:157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seybert, A., C. C. Posthuma, L. C. van Dinten, E. J. Snijder, A. E. Gorbalenya, and J. Ziebuhr. 2005. A complex zinc finger controls the enzymatic activities of nidovirus helicases. J. Virol. 79:696-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seybert, A., L. C. van Dinten, E. J. Snijder, and J. Ziebuhr. 2000. Biochemical characterization of the equine arteritis virus helicase suggests a close functional relationship between arterivirus and coronavirus helicases. J. Virol. 74:9586-9593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shen, S., J. Kwang, W. Liu, and D. X. Liu. 2000. Determination of the complete nucleotide sequence of a vaccine strain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and identification of the Nsp2 gene with a unique insertion. Arch. Virol. 145:871-883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snijder, E. J., J. C. Dobbe, and W. J. Spaan. 2003. Heterodimerization of the two major envelope proteins is essential for arterivirus infectivity. J. Virol. 77:97-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snijder, E. J., A. L. Wassenaar, L. C. van Dinten, W. J. Spaan, and A. E. Gorbalenya. 1996. The arterivirus nsp4 protease is the prototype of a novel group of chymotrypsin-like enzymes, the 3C-like serine proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 271:4864-4871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snijder, E. J., A. L. M. Wassenaar, and W. J. M. Spaan. 1994. Proteolytic processing of the replicase ORF1a protein of equine arteritis virus. J. Virol. 68:5755-5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spall, V. E., M. Shanks, and G. P. Lomonossoff. 1997. Polyprotein processing as a strategy for gene expression in RNA viruses. Semin. Virol. 8:15-23. [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Meer, Y., H. van Tol, J. K. Locker, and E. J. Snijder. 1998. ORF1a-encoded replicase subunits are involved in the membrane association of the arterivirus replication complex. J. Virol. 72:6689-6698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Dinten, L. C., J. A. den Boon, A. L. Wassenaar, W. J. Spaan, and E. J. Snijder. 1997. An infectious arterivirus cDNA clone: identification of a replicase point mutation that abolishes discontinuous mRNA transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:991-996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Dinten, L. C., S. Rensen, A. E. Gorbalenya, and E. J. Snijder. 1999. Proteolytic processing of the open reading frame 1b-encoded part of arterivirus replicase is mediated by nsp4 serine protease and is essential for virus replication. J. Virol. 73:2027-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wassenaar, A. L. M., W. J. M. Spaan, A. E. Gorbalenya, and E. J. Snijder. 1997. Alternative proteolytic processing of the arterivirus replicase ORF1a polyprotein: evidence that NSP2 acts as a cofactor for the NSP4 serine protease. J. Virol. 71:9313-9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong, T. C. 2003. Membrane structure of the human immunodeficiency virus gp41 fusion peptide by molecular dynamics simulation II. The glycine mutants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1609:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang, H., M. Yang, Y. Ding, Y. Liu, Z. Lou, Z. Zhou, L. Sun, L. Mo, S. Ye, H. Pang, G. F. Gao, K. Anand, M. Bartlam, R. Hilgenfeld, and Z. Rao. 2003. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:13190-13195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ypma-Wong, M. F., P. G. Dewalt, V. H. Johnson, J. G. Lamb, and B. L. Semler. 1988. Protein 3CD is the major poliovirus proteinase responsible for cleavage of the P1 capsid precursor. Virology 166:265-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeng, L., E. K. Godeny, S. L. Methven, and M. A. Brinton. 1995. Analysis of simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) subgenomic RNAs, junction sequences, and 5′ leader. Virology 207:543-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ziebuhr, J., G. Heusipp, and S. G. Siddell. 1997. Biosynthesis, purification, and characterization of the human coronavirus 229E 3C-like proteinase. J. Virol. 71:3992-3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ziebuhr, J., E. J. Snijder, and A. E. Gorbalenya. 2000. Virus-encoded proteinases and proteolytic processing in the Nidovirales. J. Gen. Virol. 81:853-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]