Despite great strides in technological innovations and the emergence of a wide range of treatments for wounds, non-healing wounds continue to perplex and challenge doctors. Various non-surgical approaches have been developed and numerous drugs have been introduced to aid the management of such wounds.

Figure 1.

Left: Components of four layer bandage system. Right: Four layer bandage system to treat venous ulcer (note class II compression stocking on right leg for prevention of ulceration)

Table 1.

Single layer compression bandages

| Class (level of compression) | Indication | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 3a (light (14-17 mm Hg)) | To treat simple VLU | Elset, Litepress |

| 3b (moderate (18-24 mm Hg)) | To treat VLU and ulcers secondary to lymphoedema | Tensoplus Forte, Coban |

| 3c (high (25-35 mm Hg)) | As for class 3b plus gross varicose veins in moderate sized legs | Tensopres, Setopress, Surepress |

| 3d (extra-high (36-50 mm Hg)) | To treat extensive VLU, ulcers secondary to lymphoedema, extensive varicose veins, and post-thrombotic venous insufficiency in patients with very large and oedematous legs | Elastic web bandages (blue line or red line webbing) |

VLU = venous leg ulcer.

Non-surgical treatments

Bandages and hosiery

Compression bandages are used to treat lower limb ulcers secondary to venous insufficiency (venous leg ulcers) and lymphoedema. Single layer compression bandages (elastic) are classified into four groups according to the predetermined levels of compression they provide at the ankle. Inelastic compression bandages (short stretch), when applied at full extension, improve the calf muscle pump action and exert higher pressures when the patient is upright (and walking) and lower pressures at rest. They are useful in patients who are adequately mobile. An elasticated tubular bandage (one to three layers) may be useful to treat and prevent venous leg ulcers.

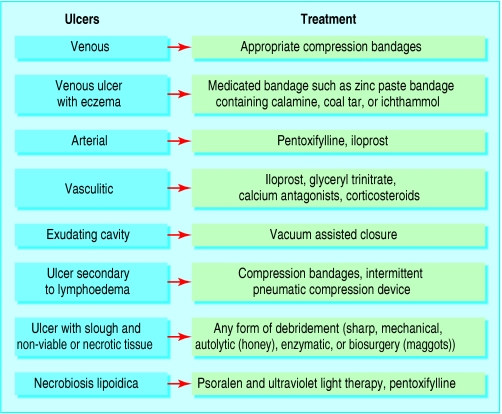

Figure 2.

Non-surgical and drug treatments to consider in the treatment of chronic ulcers

Table 2.

Caution in use of compression bandages

| • Appropriate clinical evaluation is essential before using any form of compression treatment |

| • Injudicious use may lead to serious complications, including limb gangrene |

| • Distal circulation of the limb should be carefully assessed and peripheral vascular disease excluded |

| • Caution should be exercised in patients with peripheral neuropathy |

Multilayer compression bandaging, such as the four layer method, is well established in the management of venous leg ulcers. It consists of four layers—padding, a crepe bandage, and classes 3a and 3b (UK classification) compression bandages—applied from the base of the toes to knee. Ideally, it should be left in place for four to seven days. Although effective, the bulkiness of these layers may lead to non-compliance in some patients. Its use is limited in heavily exuding ulcers as repeated dressing changes may be needed.

Figure 3.

Top left: Single layer elastic compression bandage. Top right: Inelastic (short stretch) compression bandage. Left: Three layer elasticated tubular bandage

This is the 11th in a series of 12 articles

Graduated compression hosiery (UK classes I to III) is primarily used to prevent recurrence of venous leg ulcers and to control symptoms associated with varicose veins. The use of compression hosiery below the knee is associated with increased patient adherence

Medicated bandages such as zinc paste bandages can be useful in treating some leg ulcers. They can be left undisturbed for up to a week. A zinc paste bandage containing calamine, coal tar, or ichthammol can be used if there is associated venous eczema. Medicated bandages provide no compression.

Figure 4.

Medicated bandage

Intermittent pneumatic compression

Intermittent pneumatic compression is effective in treating longstanding venous leg ulcers associated with severe oedema that are refractory to conventional compression therapy alone.

Figure 5.

Intermittent pneumatic compression device

Intermittent pneumatic compression provides compression (range 20-120 mm Hg) at preset intervals (average 70 seconds) through an electrically inflatable “boot” of variable lengths. It is generally used two hours a day for up to six weeks. It improves venous and lymphatic flow and is useful in patients with comorbidities that limit mobility. It should be used as an adjunct to, rather than a substitute for, conventional compression therapy. Care should be taken in patients with cardiac failure.

Figure 6.

Diabetic foot ulcer suitable for vacuum assisted closure therapy (far left) and vacuum assisted closure in situ (left).

Vacuum assisted closure

Vacuum assisted closure is a non-invasive, negative pressure healing technique that is used to treat a wide range of chronic, non-healing wounds.

Figure 7.

Left: Grade 4 sacral pressure ulcer suitable for vacuum assisted closure therapy. Right: Vacuum assisted closure in situ

The vacuum assisted closure device uses controlled subatmospheric pressure to remove excess wound fluid from the extravascular space, leading to improved local oxygenation and peripheral blood flow. This promotes angiogenesis and formation of granulation tissue, which are particularly useful in deep cavitating wounds to expedite “filling” of the wound space.

Figure 8.

Left: Pressure ulcer before debridement with larval (maggot) therapy. Right: The same ulcer 12 days after debridement with larval therapy (with maggots in situ)

Vacuum assisted closure is contraindicated in patients with thin, easily bruised or abraded skin and in those with neoplasms as part of the wound floor. Cost and patient adherence may be issues of concern in some cases.

Hyperbaric oxygen

The use of hyperbaric oxygen has been recommended as an adjunctive therapy to treat a variety of non-healing wounds (as many non-healing tissues are hypoxic). Treatment is given by increasing the atmospheric pressure in a chamber while the patient is breathing 100% oxygen. Side effects such as seizures and pneumothorax have been reported with hyperbaric oxygen.

A systematic review of the Cochrane database, however, has found insufficient evidence for its effectiveness in healing chronic wounds, although it might have a role in reducing the risk of major amputation in patients with diabetic foot ulcers (see third article this series).

Biosurgery (myiasis)

Biosurgery uses sterile maggots (usually of the green bottle fly, Lucilia sericata), which digest sloughy and necrotic material from wounds without damaging the surrounding healthy tissue.

They have been shown in small scale trials to be useful in the treatment of venous, arterial, and pressure ulcers. Some patients complain of increased pain in the wound, and psychological discomfort and aesthetics may be issues for some individuals.

Other approaches

Other non-surgical approaches that have a scientific basis and thus have been advocated in the treatment of chronic wounds include radiant heat dressing, ultrasound therapy, laser treatment, hydrotherapy, electrotherapy, electromagnetic therapy, and PUVA therapy (psoralen plus ultraviolet A irradiation).

However, few randomised controlled trials have studied the effectiveness of these treatments.

Further rigorous randomised controlled trials are necessary to ascertain the type of ulcers that may benefit from treatment with hyperbaric oxygen

Drugs

Pentoxifylline, a methylxanthine that improves perfusion of peripheral vascular beds, is useful in patients with ulcers secondary to peripheral vascular disease. It improves capillary microcirculation by decreasing blood viscosity and reducing platelet aggregation. It may also inhibit tumour necrosis factor-α, an inflammatory cytokine involved in non-healing wounds. Although mainly indicated for ulcers secondary to peripheral vascular disease, pentoxifylline is useful in patients with venous leg ulcer who cannot tolerate compression or in whom compression is ineffective. It may also be beneficial in rare but complex ulcers such as sickle cell ulcers, livedoid vasculitis, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Figure 9.

Arterial ulcer suitable for pentoxifylline treatment

Iloprost, a prostacyclin analogue, is an established treatment for intermittent claudication, severe limb ischaemia, and prevention of imminent gangrene, and to reduce the pain and clinical symptoms associated with Raynaud's disease. Intravenous iloprost is useful in promoting healing of arterial ulcers and vasculitic ulcers secondary to connective tissue diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and scleroderma.

Figure 10.

Left: Ulcers secondary to Raynaud's disease suitable for iloprost therapy. Right: Ulcer secondary to rheumatoid arthritis suitable for iloprost therapy

Antimicrobials including iodine based preparations and silver releasing agents are used to treat infected wounds (there may be a dose dependent effect). Antimicrobial agents target bacteria at several level (cell membrane, cytoplasmic organelle, and nucleic acid), thus minimising bacterial resistance. They can be used either on their own or in conjunction with systemic antibiotics. The many silver releasing agents, in dressing form, aim to deliver sustained doses of silver to the wound. In addition to the microbicidal effect of silver on common wound contaminants, silver may also be effective against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Figure 11.

Infected wound suitable for topical antimicrobial therapy

Glyceryl trinitrate, a nitric oxide donor, is effective in the management of chronic anal fissures when applied topically as 0.2% ointment. Nitric oxide causes vasodilatation, and uncontrolled studies have suggested a potential role for glyceryl trinitrate in treating chronic wounds of ischaemic aetiology, including vasculitic ulcers. Headache, sometimes troublesome, is the most commonly encountered side effect with glyceryl trinitrate: lower concentrations may avoid this side effect.

Figure 12.

Vasculitic ulcer suitable for treatment with glyceryl trinitrate

Calcium antagonists such as diltiazem and nifedipine are useful in treating vasculitic ulcers secondary to Raynaud's disease and connective tissue diseases. In Raynaud's disease, they restore blood flow to the digits and thus are useful in treating ulcers and the prevention of necrosis in the extremities.

Table 3.

Non-surgical approaches that have been advocated for treating chronic wounds

| Type | Mechanism of action/principle | Wound type | Evidence; current status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiant heat dressing | Improves tissue oxygenation and increases subcutaneous oxygen tension | Mainly postoperative wounds; diabetic ulcers; pressure ulcers | Limited evidence; not in routine use |

| Ultrasound therapy | Mechanical effect causing micromassage of tissue; anti-inflammatory effect (due to reduction in macrophages) | Pressure ulcers and VLU | Limited evidence; not in routine use |

| Laser | Stimulates fibroblast activity and collagen metabolism; promotes neovascularisation; inhibits inflammation | VLU, diabetic ulcers, and burns | Limited evidence; not in routine use |

| Hydrotherapy | Form of mechanical debridement; removes loosely attached devitalised tissue and other cellular debris from wound bed | Pressure ulcers, VLU, and other chronic wounds containing excess slough or necrotic tissue | Practised in USA, but not well established in UK |

| Electrotherapy | Stimulates body's endogenous bioelectric system by delivering therapeutic levels of electric current into wound | TENS* is used to treat some ischaemic ulcers, diabetic foot ulcer, and pressure ulcers | Limited evidence; TENS* used in specialist centres |

| Electromagnetic therapy | Promotes cytokine synthesis in the topically applied mononuclear cells (autologous) | Ischaemic ulcers, pressure ulcers, and VLU | Limited evidence; not in routine use |

VLU = venous leg ulcer.

Form of electrotherapy.

Systemic corticosteroids are useful in treating ulcers secondary to connective tissue diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, and other vasculitic disorders. They promote healing by attenuating the excessive inflammatory response. Long term use of corticosteroids, however, may have a detrimental effect on healing. Patients taking long term, high dose steroids should be offered bone protection with bisphosphonates.

Figure 13.

Far left: Infected leg ulcer suitable for treatment with honey. Left: Flowers from Manuka bush from which honey is extracted

Zinc, an antioxidant, used in a paste bandage may be useful in treating infected leg ulcers. Oral zinc sulphate treatment may be beneficial in patients with chronic ulcers who have low serum zinc levels.

Phenytoin, applied topically, promotes wound healing by inhibiting the enzyme collagenase. It is effective in some low grade pressure ulcers and trophic ulcers due to leprosy. The possibility of systemic absorption and toxicity has limited its use.

Retinoids (derived from vitamin A) have an impact on wound healing through their effects on angiogenesis, collagen synthesis, and epithelialisation. Vitamin A is necessary for normal epidermal maintenance. Although the value of retinoids in chronic wounds is unclear, topical tretinoin (0.05-0.1%) has been shown to accelerate re-epithelialisation of dermabraded and chemically peeled wounds in humans, and partial and full thickness wounds in animal models.

Analgesics are needed for many ulcers. They may range from simple analgesics to opiates in individuals whose the pain is severe. Pain from ulcers associated with neuropathy may benefit from treatment with certain tricyclic antidepressants (such as amitriptyline) or antiepileptic drugs (such as gabapentin). Intractable pain may necessitate intervention by specialist pain management teams.

Table 4.

Effect of some commonly used drugs on wound healing

| Class and name of drug | Effects |

|---|---|

| NSAIDs Ibuprofen | Affects inflammatory phase by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase production; reduces tensile strength of wound |

| Colchicine | Affects inflammatory phase; affects proliferative phase by decreasing fibroblast proliferation; affects remodelling phase by degrading newly formed extracellular matrix |

| Corticosteroids (prednisolone) | Affects haemostatic phase by decreasing platelet adhesion; affects inflammatory phase by affecting phagocytosis; affects remodelling phase by reducing fibroblasts activity and inhibiting collagen synthesis |

| Antiplatelets (aspirin) | Affects haemostatic phase by inhibiting platelet aggregation; inhibits inflammation mediated by arachidonic acid metabolites |

| Anticoagulants Heparin | Affects haemostatic phase by its effect on fibrin formation; can lead to thrombus formation by causing thrombocytopaenia (white clot syndrome) |

| Warfarin | Affects haemostatic phase by its effect on fibrin formation; can cause tissue necrosis and gangrene by release of atheromatous plaque emboli in form of microcholesterol crystals (blue toe syndrome) |

| Vasoconstrictors (nicotine, cocaine, adrenaline) | Affects proliferative phase by inhibiting neovascularisation and decreasing granulation tissue formation; impairs microcirculation and increases graft rejection and ulcer necrosis |

NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Natural products

Honey, of the pasture and manuka varieties, has some antibacterial action, inhibits excessive inflammatory response, and promotes autolytic debridement. It is available as an impregnated dressing or as a gel. Honey is used in the treatment of a range of chronic wounds. Clinical data to support its widespread use are limited, however, with insufficient evidence on the type of wounds that may benefit and the amount and duration of application required.

Many other natural products—including yoghurt, tea tree oil, and potato peeling—have been used in various parts of the world to treat ulcers with varying degrees of success; controlled studies are lacking.

Drugs and agents that impair healing

Vasoconstrictors, such as nicotine, cocaine, adrenaline (epinephrine) and ergotamine, cause tissue hypoxia by adversely affecting the microcirculation, leading to impaired wound healing. They should be avoided in patients with acute, surgical, or chronic wounds. Little evidence exists to suggest that immunosuppressants and antineoplastic drugs (such as azathioprine, ciclosporin, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate) affect wound healing in humans. Patients taking immunosuppressants, however, have a slightly increased risk of developing malignant ulcers. A biopsy should be taken if an ulcer develops in these patients.

The photos of maggot therapy were provided by Dr S Thomas of Zoobiotic, and the photo of the manuka bush was provided by Dr R Cooper, University of Wales Institute, Cardiff.

Competing interests: For series editors' competing interests, see the first article in this series.

The ABC of wound healing is edited by Joseph E Grey (joseph.grey@cardiffandvale.wales.nhs.uk), consultant physician, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff and Vale NHS Trust, Cardiff, and honorary consultant in wound healing at the Wound Healing Research Unit, Cardiff University, and by Keith G Harding, director of the Wound Healing Research Unit, Cardiff University, and professor of rehabilitation medicine (wound healing) at Cardiff and Vale NHS Trust. The series will be published as a book in summer 2006.

Further reading and resources

- • Cullum N, Nelson EA, Fletcher AW, Sheldon TA. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(2): CD000265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- • Berliner E, Ozbilgin B, Zarin DA. A systematic review of pneumatic compression for treatment of chronic venous insufficiency and venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg 2003;37: 539-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Kranke P, Bennett M, Roeckl-Wiedmann I, Debus S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(1): CD004123. [DOI] [PubMed]

- • Eginton MT, Brown KR, Seabrook GR, Towne JB, Cambria RA. A prospective randomized evaluation of negative-pressure wound dressings for diabetic foot wounds. Ann Vasc Surg 2003;17: 645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Karukonda SR, Flynn TC, Boh EE, McBurney EI, Russo GG, Millikan LE. The effects of drugs on wound healing—part II. Specific classes of drugs and their effect on healing wounds. Int J Dermatol 2000;39: 321-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]