Abstract

Experimental evidence for human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) recombination was recently obtained in one exceptional individual with paternal inheritance of mtDNA1 and in an in vitro cell culture system2. Whether mtDNA recombination is a common event in humans remained to be elucidated. To detect mtDNA recombination in human skeletal muscle, we have analyzed the distribution of alleles in individuals with multiple mtDNA heteroplasmy using single-cell PCR and allele-specific PCR. In ten out of ten individuals who harbored a heteroplasmic D-loop mutation and a distantly located tRNA point mutation or a large deletion, we observed a mixture of four allelic combinations (tetraplasmy), a hallmark of recombination. Reassuringly, 12 out of 14 individuals with closely located heteroplasmic D-loop mutation pairs contained a mixture of only three types of mitochondrial genomes (triplasmy), consistent with the absence of recombination between adjacent markers. These findings indicate that mtDNA recombination is common in human skeletal muscle.

Inter-molecular heterologous recombination of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which has been shown to occur in plants, fungi and protists mitochondria as well as in certain mussel and fish species,3 is controversial in humans4-14. Experimental evidence for mtDNA recombination was recently obtained in one individual with paternal inheritance of mtDNA1 and in an in vitro cell culture system obtained by fusion of two human cybrid cell lines2 (see, however, ref. 15). Due to the specific and rare features of the individual case1,16 - no further cases of paternal inheritance of mtDNA have been reported so far17,18 - further work is required to determine the in vivo impact of human mtDNA recombination.

To detect mtDNA recombination in human skeletal muscle, we analyzed the distribution of allelic combinations in individuals with multiple mtDNA heteroplasmy, i.e. individuals carrying a mixture of wild type and a mutation at more than one location in their mitochondrial genome. If the main source of this mtDNA heteroplasmy is clonal expansion of early developmental mutations19, then only two single de novo mutational events are sufficient for generation of double heteroplasmy. In the absence of mtDNA recombination, mutants originally generated on different mtDNA molecules remain separated and thus only three types of mtDNA molecules (triplasmy) can be expected: the original wild type (W1W2), and molecules with one (M1W2) or the other (W1M2) position mutated. In contrast, a mtDNA crossover between these two positions would lead to the appearance of a fourth (“mixed”) genotype with a second mutant on the already mutated DNA copy. As a result, all four possible allelic combinations (tetraplasmy) will be present in the tissue: the wild type (W1W2), two single mutants (M1W2), (W1M2), and, additionally, the double mutant (M1M2). It should be noted, however, that in some cases heteroplasmy may result from recurrent mutation of the same nucleotide position on different DNA molecules. Obviously, recurrent mutations will also result in tetraplasmy. Therefore, the analysis of allelic combinations in individuals with multiple mtDNA heteroplasmy allows one to demonstrate recombination if the possibility of recurrent mutation can be excluded.

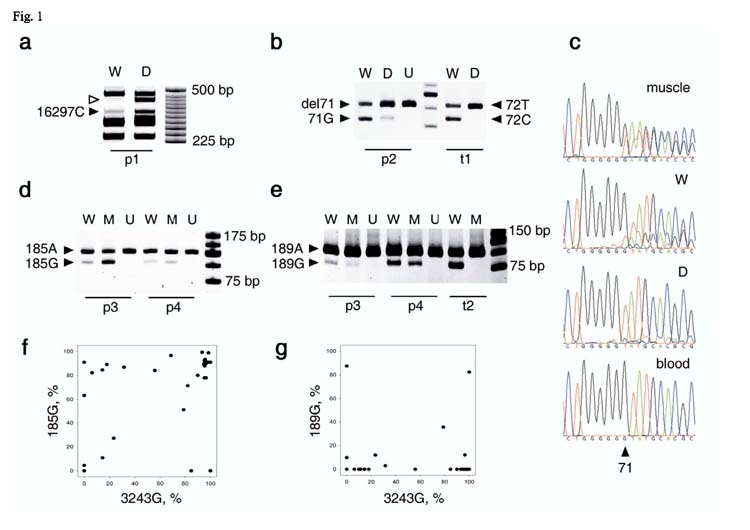

We identified ten patients harboring heteroplasmic pathogenic mtDNA mutations in the coding region who carried one additional heteroplasmic D-loop mutation at np71, np72, or np16297, or two additional heteroplasmic D-loop mutations at np185 and np189. In these individuals we determined the corresponding allelic distributions of mutations. As shown in Table 1, all of the ten individuals showed a tetraplasmic distribution of all coding region mtDNA mutations in respect to the distantly located D-loop mutations. This result was obtained by allele-specific PCR for patients p1-p5 and p7-p10. Selected examples of this analysis (for p1-p4) are shown in Fig. 1a-e. It can be seen that both alleles of the corresponding D-loop mutation were always detectable after allele-specific amplification of the coding region mutant (D for deletion or M for point mutation, respectively) or wild type mtDNA (W). PCR is known to generate artificial recombinants via template-to-template jumping20. To exclude this artifact, control triplasmic mixtures (t1 and t2), each consisting of three of four possible allelic combinations of double mutations, were subjected to the same procedures as the patient samples. As expected, the controls remained triplasmic throughout the procedure (Fig. 1b and e).

Table 1.

Degrees of heteroplasmy of coding region and D-loop mutations in bulk muscle and allelic distribution of individual mutations

| Patient | Mutations | Content in bulk muscle* |

Allelic distribution (Coding region / D-loop)** |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coding region mutation | D-loop mutation | W1W2 | W1M2 | M1W2 | M1M2 | ||

| p1 | del8809-13035/T16297C | 52 % | 24 ± 3 % | 45 % | 3 % | 23 % | 29 % |

| p2 | del12103-14411/del71 | 45 % | 59 ± 2 % | 36 % | 19 % | 9% | 36 % |

| p3 | A3243G/A185Ga | 26 ± 5% | 26 ± 3 % | 55 % | 19 % | 11 % | 15 % |

| A3243G/A189G | 3 ± 1 % | 71 % | 3 % | 25 % | 0.5 % | ||

| p4 | A3243G/A185Ga | 50 ± 3 % | 21 ± 3 % | 40 % | 10 % | 40 % | 10 % |

| A3243G/A189G | 8 ± 2 % | 46 % | 4 % | 45 % | 5 % | ||

| p5 | A3243G / T72C | 66 ± 1 % | 8 ± 2 % | 32 % | 2 % | 61 % | 5 % |

| p6 | G5835Ab/T72C | 72 ± 0.5 % | 50 ± 7 % | 23 %c | 5 %c | 19 %c | 53 %c |

| p7 | del10311-15571/T72c | 51 % | 7 ± 0.5 % | 46 % | 3 % | 50 % | 1 % |

| p8 | del9098-14651/T72C | 89 % | 3 ± 1 % | 10 % | 1 % | 88 % | 1 % |

| p9 | del10198-13755/T72C | 65 % | 3 ± 1 % | 33 % | 1.7 % | 65 % | 0.3 % |

| p10 | del11032-13232/T72C | 53 % | 38 ± 1 % | 24 % | 24 % | 36 % | 16 % |

The degrees of heteroplasmy in skeletal muscle have been determined by Southern blotting (deletions) or RFLP analysis (point mutations). Averages ± SD are given for at least two independent determinations.

The allelic distribution has been determined by allele-specific PCR and restriction analysis and calculated according to the procedure described in Methods.

Wild type according to the Cambridge reference sequence26.

Novel pathogenic tRNA(Tyr) point mutation.

Determined from single-fiber data (33 fibers were analyzed for both G5835A and T72C).

Figure 1.

Tetraplasmic allelic distributions of double heteroplasmic mutations in patients p1-p4 prove the presence of recombination. W, wild-type; D, deletion; M, point mutation; U, undigested PCR product for control. t1-t2, triplasmic controls. a, The 16297C mutant-specific restriction digestion product (filled arrowhead) is present in both deleted (D) and wild-type (W) mitochondrial genomes in patient p1. Since 16297T is also present in both deleted and wild-type mtDNA (not shown), the sample is tetraplasmic. The absence of the deletion-specific band (empty arrowhead) in lane W confirms excellent specificity of the wild type-specific PCR. b, del71 mutation-specific and 71G wild type-specific bands are present both in the wild type (W) and in the del12103-14411-specific (D) PCR products from patient p2. In the triplasmic control (t1), only the three input allelic combinations are detectable. t1 is a mixture of the wild-type (72T), and single mutants 72C and del8426-14138, used to imitate the p2 mutations. c, Distribution of the heteroplasmic del71 mutation between del12103-14411 and wild-type mitochondrial genomes of individual p2 as shown by direct sequencing. “Muscle”, “blood” indicate bulk DNA samples. W, wild type-specific PCR product from muscle; D, deletion-specific PCR product. d, e, Allelic distribution of mutants A185G (d) and A189G (e) and the A3243G MELAS mutation in patient p3 and p4. Note that four bands corresponding to the four allelic combinations are present in each case. t2 is the corresponding triplasmic control (a mixture of 3243G/189A, 3243A/189A, and 3243A/189G) f, g, Distribution of 3243/185 (f) and 3243/189 (g) alleles in individual muscle fibers of patient p3. Note the existence of fibers with each of the four allelic combinations in almost pure state (dots in the corners of the graphs).

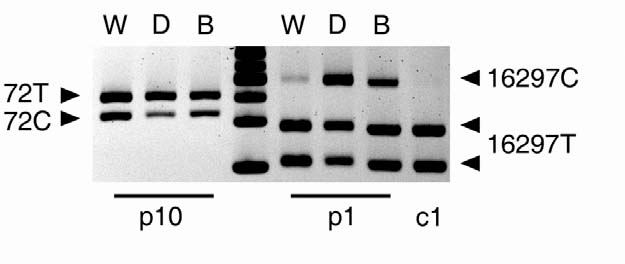

Two additional experiments were performed to exclude the possibility of PCR artifacts in our system. First, for patients p1 and p10 who carry deleted mtDNA, the deleted and the wild type molecules were separated prior to any PCR by high resolution agarose gel electrophoresis. In this setting, the DNA species potentially subject to artificial recombination are separated prior to PCR. The putative presence of tetraplasmy was then investigated by restriction analysis. As shown in Fig. 2, tetraplasmy was confirmed; moreover, the distribution of four allelic combinations was (within experimental error) identical to that obtained using allele-specific PCR (Supplementary Table 1 online).

Figure 2.

Tetraplasmic distribution of alleles is confirmed using pre-PCR separation by gel electrophoresis, which is not subject to PCR artifacts. PvuII-digested total muscle DNA samples from two patients (p10 and p1) carrying large scale deletions were subjected to high resolution agarose gel electrophoresis to separate the wild-type and deleted mtDNA molecules. Mutation loads of D-loop mutations (72C in p10 and 16297C in p1) were determined independently in both the wild-type (W) and deleted (D) electrophoretic fractions by PCR and restriction digestion (cf. Supplementary Table 1 online). The purity of individual fractions was confirmed by multiplex PCR (Supplementary Figure 1 online). Rightmost lane, 25-bp DNA ladder.

In the second experiment, single-fiber genotype analysis was performed. This approach is based on the fact that point mutations in mtDNA are frequently subject to intracellular clonal expansions21, which result in homoplasmic fibers with almost pure mitochondrial genotype. To confirm tetraplasmy, it is sufficient to detect homoplasmic fibers carrying each of the four genotype combinations in a pure form. The analysis of allelic combinations in single muscle fibers was performed for patients p3, p4 and p6; Fig. 1f and g shows p3 as an example. Note that the data points in each of the four corners of the graphs represent fibers with almost pure (W1W2, M1W2, W1M2 and M1M2) genotypes. Thus the fact that all four corners are populated by data points implies that all four genotypes are present in muscle and thus the tissue is tetraplasmic.

As long as PCR artifacts are excluded (cf. Supplementary Note online), two mechanisms might be responsible for tetraplasmy: (i) recurrence of the mutations or (ii) mtDNA recombination. Since pathogenic mutations are rare in the general population, recurrence of these mutations is highly unlikely. To evaluate the probability of recurrence of D-loop mutations we relied on the frequency of the heteroplasmic state of these mutations in our collection of over three hundred skeletal muscle and brain DNA samples (Supplementary Table 2 online). Our data indicate a very low statistical likelihood for recurrence of the T16297C and the del71 D-loop mutations (we detected each mutation in only one out of all screened skeletal muscle and brain samples, respectively). The sites at np72, np185 and np189 were more frequently observed in the heteroplasmic state indicating a higher probability of a recurrent mutation.

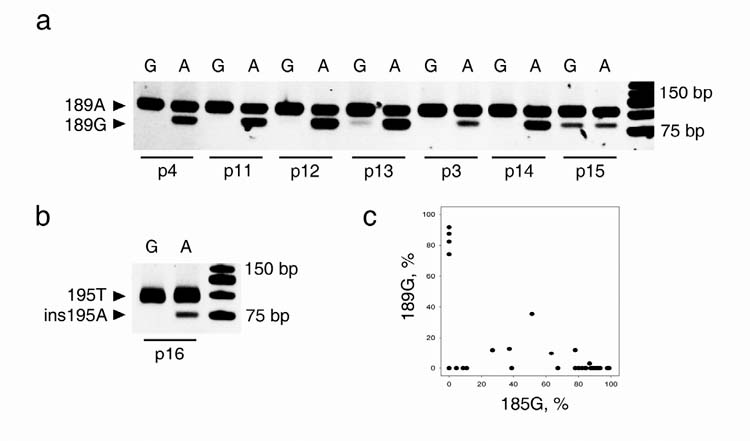

To directly evaluate the probability of recurrent mutation in the D-loop, we investigated allelic combinations in individuals with heteroplasmic D-loop mutations at adjacent loci, which are unlikely to recombine (cf. refs. 1,4). We identified seven individuals harboring A185G/A189G double heteroplasmy in skeletal muscle (p3, p4 and p11-p15) and a further six individuals with A185G/A189G double heteroplasmy in the brain. Furthermore, in one individual, we detected A185G/ins195A double heteroplasmy in skeletal muscle (p16). As expected, for the mutation pairs A185G/A189G (Fig. 3a and c) and A185G/ins195A (Fig. 3b), we observed a mixture of three types of mitochondrial genomes (triplasmy) in six out of eight skeletal muscle samples and in six out of six brain samples (data not shown). In accordance with previous work22 on a single patient with A185G/A189G heteroplasmy this indicates that double heteroplasmy was largely created by clonal expansion of only two single de novo mutational events in most (12 out of 14) of the investigated individuals with A185G/A189G and A185G/ins195A heteroplasmy. Since mtDNA recombination is unlikely to cause the tetraplasmy observed in individuals p13 and p15 (Fig. 3a) due to the close location of sites1,4, a low incidence of recurrence of the A185G/A189G mutations has to be considered. This is in line with the observed higher frequency of A185G and A189G heteroplasmy in skeletal muscle and brain tissue in comparison to the T16297C, del71 and T72C mutations (cf. Supplementary Table 2 online). Therefore, it appears extremely improbable that the tetraplasmy in the ten individuals with coding region mtDNA mutations presented in Table 1 might be caused by recurrence of D-loop mutations. In this context it is also important to emphasize that patients p3 and p4 who carry three heteroplasmic mutations (A3243G, A185G, A189G) show triplasmy (no recombination) between the close sites at np185 and np 189 (Fig. 3a and c) but tetraplasmy (indicating recombination) between the distant sites at np3243 and np185 or np189, respectively (Fig. 1d-g). Taken together, only mtDNA recombination events can explain the observed tetraplasmic distribution pattern of alleles.

Figure 3.

Co-segregation of closely spaced alleles in skeletal muscle of double heteroplasmic individuals argues against recurrence of mutations. In two-round PCR reactions, products specific for either one (A) or the other (G) allele of heteroplasmic nucleotide position 185 were amplified first, then proportions of the other heteroplasmic mutation were determined in both allele-specific reactions by mismatch-PCR and restriction digestion. a, Triplasmic and tetraplasmic distributions of A185G heteroplasmy with A189G heteroplasmy in skeletal muscle. Note the lack of the digested band in the ‘G’ lanes for most individuals, and its presence in individuals p13 and p15. b, Triplasmic segregation of A185G heteroplasmy with a heteroplasmic single nucleotide insertion at position 195. c, Triplasmic distribution of 185 and 189 alleles in individual muscle fibers of individual p3 (Figure 3a). Note the absence of data points in the upper right corner corresponding to the 185G/189G haplotype.

This interpretation seems to be in contrast to previous reports23-25 failing to detect mtDNA recombinants in certain patients with mtDNA diseases. Possible reasons for this discrepancy might be either the segregational loss of one allele (e.g. by selection) or the low frequency of allelic recombination (e.g. limited contact between heterologous molecules). For our presented patients we cannot determine which are the “native” molecules and which the recombinant ones, because the history of the evolution of native alleles in the patient’s muscle is unknown. One can estimate the minimum fraction of recombinants, i.e. the fraction of the least represented allelic combination to be between 0.3% and 16% (Table 1). This minimum fraction is highly variable between different individuals and should be interpreted with caution. Mutations used as recombination markers and hence recombinants themselves were subject to global clonal expansions in muscle of the individuals under study. Thus the fraction of recombinants may reflect the efficiency of clonal expansion rather than the intrinsic recombination rate.

Taken together, our data indicate the presence of mtDNA recombination events in skeletal muscle of ten individuals. Thus mtDNA recombination in humans is not limited to a single exceptional individual 1,16. This observation is highly relevant to the mechanisms of progression and expression of mitochondrial DNA disorders and should be considered for future gene therapeutic strategies. Our observations are of interest for the evolutionary studies of human mtDNA, though they are limited to a somatic tissue.

METHODS

Subjects and controls

A list of patients with mtDNA mutations in the coding region investigated in this study is shown in Supplementary Table 3 online. Control muscle DNA samples were isolated from skeletal muscle biopsies of patients with neurological disorders. Brain samples were obtained from surgical material removed during epilepsy surgery. The study was conducted following the guidelines of the University of Bonn Ethical Commission and informed consent was obtained from all investigated subjects.

mtDNA mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from 30 mg skeletal muscle specimens with the QiaAmp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Large-scale deletions were quantified by Southern-blotting of PvuII linearized genomic DNA using digoxigenin-labeled isolated human mitochondrial DNA as full-length mtDNA probe. The presence of duplications was excluded by PmeI or BamHI digestion. The individual bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (DIG Luminescent Detection Kit; Boehringer Mannheim, Germany) and quantified by densitometry and corrected for the length difference. The PCR products specific for deleted or non-deleted mitochondrial genomes and encompassing polymorphic D-loop sites were amplified by using a D-loop primer together with primers located inside the deletion region (for wild type product), outside the deletion close to the far end breakpoint (for deletion product), or between the deletion and the D-loop (for total amount), respectively. The detailed list of primers used in specific cases is shown in Supplementary Table 4 online and a schematic representation of positions of mutations and used PCR primers is shown in Supplementary Figure 2 online. Conditions of the amplification were as follows: 95°C for 2 min 30 sec; 35 cycles of 92°C for 25 sec and 68°C for 4 min; finally 72°C for 7 min. To detect the T16297C polymorphism, PCR products were digested with MseI restriction endonuclease. Double digestion with restriction endonucleases SphI and BanII was carried out to quantify the amounts of the T72C polymorphism. SphI served for the detection of the 72C allele, while BanII provided digestion fragments for the estimation of the total amount of the PCR product. Restriction fragments were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by SYBR Green I staining (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany). Proportions of wild-type and mutant mitochondrial DNA were estimated from band intensities using the Image J analysis software. The putative effects of heteroduplex formation on mutant quantification were tested in control experiments (Supplementary Figure 3 online).

In cases of the A3243G MELAS mutation allele-specific primers were used together with a D-loop primer (Supplementary Table 4 online) to amplify long PCR products. To increase allele specificity the allele-specific primers contained a mismatch nucleotide. The number of amplification cycles was restricted to 20. An aliquot of the long PCR products was subsequently used as a template in a second round of mismatch PCR. A similar two-round PCR method was used in the del12103-14411/del71 case, and to examine distribution of D-loop polymorphisms between alleles of the A185G polymorphic site.

Mismatch-primers were used to generate an appropriate site for RFLP analysis if a natural site was not available. These mismatch-primer pairs are listed in Supplementary Table 4 online. To detect the 185G and 189G alleles in PCR products, Cac8I restriction endonuclease was used. The del71 allele was quantified by BslI digestion, the 72C allele by BglI digestion, the ins195A polymorphism by NsiI digestion. The novel pathogenic G5835A mutation was detected by digesting mismatch-PCR products with BanII endonuclease.

The allelic distributions for double heteroplasmies were determined in two steps. First, the mutant load for the first mutation of the two was determined. For example, in the case of p1, the load of deletion (52%) was determined by Southern blot of the total DNA. Then DNA was subject to two allele-specific PCRs, each of which amplified either wild type or the mutant molecules with respect to the first mutation (e.g. the deletion and the wild type in case of p1). Each of the two PCR products was then subject to RFLP to determine the load of the second mutation. In case of p1, the load of T16297C in the deletion-specific PCR was determined to be 56% (cf. Supplementary Table 1 online, note that for samples other than p1 and p10 these data are not shown), hence, for example, the load of the deletion/16297C genotype (M1M2 in Table 1) is 0.52 × 0.56 = 0.29.

Direct sequencing of PCR products was carried out on an automatic sequence analyser (ABI 377, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Single-fiber PCR analysis

10-μm frozen sections of skeletal muscle were placed on slides with poly-L-lysine treated polyethylene naphthalate (PEN) membrane, and were immersed sequentially in 70% ethanol, 95% ethanol, absolute ethanol, and xylene. Single fibers from air-dried samples were cut using the P.A.L.M. MicroBeam system operating with a nitrogen laser (P.A.L.M., Bernried, Germany) and catapulted to a tube cap containing 20 μl magnesium-free PCR buffer, 10x diluted TE buffer and 0.5% Tween 20. After a short centrifugation and incubation for 1 hour at room temperature, samples were divided into 2-3 aliquots and directly subjected to mismatch-PCR and RFLP analysis.

High resolution agarose gel electrophoresis.

Total DNA isolated from muscle tissue was linearized with PvuII. 2 μg of DNA was loaded on 0.8% agarose gel and subjected for electrophoresis at 1 V/cm for 48 hours. The bands of interest were excised from the gel, DNA was extracted using a QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and subjected to PCR.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by research grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ku 911/11-3, Schr 562/4-1 and TR3-A7) and the BMBF (01GZ0308) to WSK and by NIH grant nos. ES11343, AG19787, and AG18388 to KK. We would like to thank Dr. A. de Grey for his comments on the manuscript. The technical assistance of Ulrike Strube is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kraytsberg Y, et al. Recombination of human mitochondrial DNA. Science. 2004;304:981. doi: 10.1126/science.1096342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Aurelio M, et al. Heterologous mitochondrial DNA recombination in human cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:3171–3179. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rokas A, Ladoukakis E, Zouros E. Animal mitochondrial DNA recombination revisited. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003;18:411–417. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awadalla P, Eyre-Walker A, Smith JM. Linkage disequilibrium and recombination in hominid mitochondrial DNA. Science. 1999;286:2524–2525. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arctander P. Mitochondrial recombination? Science. 1999;284:2090–2091. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2089e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merriweather DA, Kaestle FA. Mitochondrial recombination? Science. 1999;285:837. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.835g. continued. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kivisild T, Villems R. Questioning evidence for recombination in human mitochondrial DNA. Science. 2000;288:1931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorde LB, Bamshad M. Questioning evidence for recombination in human mitochondrial DNA. Science. 2000;288:1931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar S, Hedrick P, Dowling T, Stoneking M. Questioning evidence for recombination in human mitochondrial DNA. Science. 2000;288:1931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsons TJ, Irwin JA. Questioning evidence for recombination in human mitochondrial DNA. Science. 2000;288:1931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elson JL, et al. Analysis of European mtDNAs for recombination. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:145–153. doi: 10.1086/316938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrnstadt C, et al. Reduced-median-network analysis of complete mitochondrial DNA coding-region sequences for the major African, Asian, and European haplogroups. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1152–1171. doi: 10.1086/339933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JM, Smith NH. Recombination in animal mitochondrial DNA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:2330–2332. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagelberg E. Recombination or mutation rate heterogeneity? Implications for Mitochondrial Eve. Trends Genet. 2003;19:84–90. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato A, et al. Rare creation of recombinant mtDNA haplotypes in mammalian tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.; U.S.A.. 2005. pp. 6057–6062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz M, Vissing JN. Paternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:576–580. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filosto M, et al. Lack of paternal inheritance of muscle mitochondrial DNA in sporadic mitochondrial myopathies. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54:524–526. doi: 10.1002/ana.10709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz M, Vissing J. No evidence for paternal inheritance of mtDNA in patients with sporadic mtDNA mutations. J. Neurol. Sci. 2004;218:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coller HA, et al. High frequency of homoplasmic mitochondrial DNA mutations in human tumors can be explained without selection. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:147–150. doi: 10.1038/88859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pääbo S, Irwin DM, Wilson AC. DNA damage promotes jumping between templates during enzymatic amplification. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:4718–4721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nekhaeva E, et al. Clonally expanded mtDNA point mutations are abundant in individual cells of human tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.; U S A. 2002. pp. 5521–5526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khrapko K, Nekhaeva E, Kraytsberg Y, Kunz W. Clonal expansions of mitochondrial genomes: implications for in vivo mutational spectra. Mutat. Res. 2003;522:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohno K, et al. MELAS- and Kearns-Sayre-type co-mutation with myopathy and autoimmune polyendocrinopathy. Ann. Neurol. 1996;39:761–766. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bidooki SK, Johnson MA, Chrzanowska-Lightowlers Z, Bindoff LA, Lightowlers RN. Intracellular mitochondrial triplasmy in a patient with two heteroplasmic base changes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;60:1430–1438. doi: 10.1086/515460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zsurka G, et al. Tissue dependent co-segregation of the novel pathogenic G12276A mitochondrial tRNALeu(CUN) mutation with the A185G D-loop polymorphism. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:e124. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.022566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson S, et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290:457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.