Abstract

Heat-shock protein of 47 kDa (Hsp47) is a molecular chaperone that recognizes collagen triple helices in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Hsp47-knockout mouse embryos are deficient in the maturation of collagen types I and IV, and collagen triple helices formed in the absence of Hsp47 show increased susceptibility to protease digestion. We show here that the fibrils of type I collagen produced by Hsp47-/- cells are abnormally thin and frequently branched. Type I collagen was highly accumulated in the ER of Hsp47-/- cells, and its secretion rate was much slower than that of Hsp47+/+ cells, leading to accumulation of the insoluble aggregate of type I collagen within the cells. Transient expression of Hsp47 in the Hsp47-/- cells restored normal extracellular fibril formation and intracellular localization of type I collagen. Intriguingly, type I collagen with unprocessed N-terminal propeptide (N-propeptide) was secreted from Hsp47-/- cells and accumulated in the extracellular matrix. These results indicate that Hsp47 is required for correct folding and prevention of aggregation of type I collagen in the ER and that this function is indispensable for efficient secretion, processing, and fibril formation of collagen.

INTRODUCTION

Collagen is the most abundant protein in mammals and plays various roles as a component of the extracellular matrices. Twenty-seven types of collagen consisting of specific α-chains that are encoded by >40 different genes have been identified so far (Boot-Handford et al., 2003). These proteins are classified into five subfamilies: 1) fibril-forming collagens, 2) network-forming collagens, 3) fibril-associated collagens with interrupted triple helices (FACITs), 4) transmembrane collagens, and 5) other types of collagens (Prockop and Kivirikko, 1995). Among them, type I collagen is a typical fibril-forming collagen and a major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM), whereas type IV collagen is a nonfibrillar network-forming collagen found in basement membranes (BMs). Collagen is crucial for various biological functions, and mutations of collagen are known to cause various collagen-related diseases, including osteogenesis imperfecta and the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (Myllyharju and Kivirikko, 2004). Type I collagen, composed of two α1 chains and one α2 chain, can be divided into three major domains: N-terminal propeptide (N-propeptide), central triple helical domain, and C-terminal propeptide (C-propeptide) (Hulmes, 2002). Newly synthesized polypeptides of procollagen are cotranslationally transferred into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and are assembled at the C-propeptide region where they undergo disulfide bond formation. Triple helix formation proceeds from the C terminus to the N terminus in a zipper-like manner (Bachinger et al., 1980; Engel and Prockop, 1991; Bulleid et al., 1997), and the N- and C-propeptides are processed from the collagen helices during or immediately after secretion by the N-proteinase ADAMTS-2 and the C-proteinase BMP-1, respectively (Dombrowski and Prockop, 1988; Li et al., 1996). Finally, collagen molecules self-assemble into supramolecular structures, resulting in the formation of collagen fibrils or BMs (Hulmes, 2002). During procollagen biosynthesis in the ER, several molecular chaperones are involved in assisting the correct folding of collagen in the cell. These molecular chaperones include BiP/Grp78, Grp94, protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), prolyl 4-hydroxylase (P4H), and heat-shock protein of 47 kDa (Hsp47) (Chessler and Byers, 1993; Ferreira et al., 1994; Lamande et al., 1995; Wilson et al., 1998; Walmsley et al., 1999; Nagata, 2003). Hsp47 was first identified as a collagen binding protein residing in the ER (Nagata et al., 1986; Saga et al., 1987) and functions as a collagen-specific molecular chaperone (Nagai et al., 2000; Tasab et al., 2000). Hsp47 transiently associates with procollagen in the ER and dissociates before reaching the cis-Golgi (Satoh et al., 1996). Hsp47 preferentially recognizes collagen triple helices (Koide et al., 2002; Tasab et al., 2002), whereas PDI and P4H bind single chains of procollagen (Walmsley et al., 1999; Bottomley et al., 2001). We previously found that Hsp47-knockout mice (Hsp47-/-) are embryonically lethal and display disrupted BMs with no silver staining-positive fibrillar structures in the ECM (Nagai et al., 2000). Furthermore, type I collagen secreted from Hsp47-/- fibroblasts was shown to be more susceptible to protease digestion. More recent studies indicated that type IV collagen is absent from BMs but present in dilated ER in the Hsp47-/- embryos (Marutani et al., 2004) and that type IV collagen is slowly secreted from Hsp47-/- embryonic stem cells and sensitive to protease digestion (Matsuoka et al., 2004). These results indicated that Hsp47 is required for the maturation of collagen types I and IV in the ER. However, in vivo mechanisms for the Hsp47-assisted maturation of collagen are largely unknown.

Here, we report that fibrils of type I collagen secreted from Hsp47-/- fibroblasts have abnormally thin and branched structures. We also show that fibrils deposited in the ECM unexpectedly contained procollagen N-propeptides. In Hsp47-/- cells, type I procollagen was accumulated in the ER due to slow secretion and formed NP-40-insoluble aggregates. We discuss the roles of Hsp47 in the productive folding of type I collagen and in the prevention of aggregate formation in the ER.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Transfection

Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- mouse embryo fibroblasts (Nagai et al., 2000) and Balb/3T3 cells were cultured in 10% fetal bovine serum (Dainippon Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan)/DMEM (high glucose) in the presence of ascorbic acid phosphate (136 μg/ml) unless otherwise indicated. Transfection with mouse Hsp47 expression vector (Nagai et al., 2000) was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. All the experiments except pulse-chase experiment were performed 3 d after the cell culture became confluent.

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal antibodies to Hsp47, PDI (Stressgen Biotechnologies, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada), actin (C4) (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), GM130 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against mouse collagen type I (AB765P; Chemicon International) were obtained from the indicated sources. Rabbit antibodies against the N-propeptide and C-propeptide of the type I collagen α1 chain (LF39 and LF41, respectively) (Fisher et al., 1995) were kindly provided from Dr. L. W. Fisher (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-mouse or rabbit IgG (BioSource, Nivelles, Belgium), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse or rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-mouse or rabbit IgG, and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used as secondary antibodies.

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins were extracted from fibroblasts using cell extraction buffer containing 0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.15 M NaCl, 5.0 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, and protease inhibitors [2.0 mM N-ethylmaleimide, 2.0 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin and pepstatin] at 4°C. After centrifugation, soluble protein in the extract was quantified according to the method of Bradford (Bradford, 1976). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (Laemmli, 1970) using 8% gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose filters. Filters were blocked in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% skim milk, and specific binding of antibody was detected by developing with tetrazolium bromochloroindolylphosphate and nitro blue tetrazolium in 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9.8, containing 1 mM MgCl2. Antibody against type I collagen C-propeptide (LF-41) was used for detecting procollagen α1 chain.

Metabolic Labeling

Cells were cultured in the presence of 3.9 MBq/ml 35S-labeled Met and Cys (Express 35S protein labeling mixture; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA) in medium containing ascorbic acid phosphate, but lacking fetal calf serum and unlabeled Met or Cys, for 10 min. For pulse-chase experiments, labeled cells were chased for appropriate periods in medium containing excess unlabeled Met and Cys. Soluble proteins were extracted in cell extraction buffer and anti-type I collagen antibody (AB765P) was added to cell extracts or culture media. After incubation at 4°C overnight, protein A-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow resin (Pharmacia Biotechnology, Wikstroms, Sweden) was added to the mixture, and resin was recovered by centrifugation. Immunocomplexes bound to the resin were washed in a modified cell extraction buffer containing 0.4 M NaCl. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using 8% gels and fixed in saturated trichloroacetic acid. After soaking in 1 M sodium salicylic acid, the gels were dried and exposed to x-ray film.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were washed in PBS and fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min. After washing three times, fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. Permeabilized cells were blocked for nonspecific protein binding by incubating them in 2% goat serum/phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min. After incubation with specific antibodies, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated anti-mouse or rabbit IgG. Immunofluorescence was observed through a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Electron Microscopy

Cultured cells were rinsed in serum-free cell culture media (SFM) and fixed with 1.5% glutaraldehyde, 1.5% paraformaldehyde, and 0.05% tannic acid in SFM for 30 min. After rinsing in SFM, cells were fixed with 1% OsO4 and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol to 100%. After rinsing in propylene oxide, cells were infiltrated and embedded in Spurrs epoxy resin. Sections (80 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined on a Philips EM410LS transmission electron microscope.

Immunoelectron Microscopy

The preembedding silver enhancement immunogold method was performed for immunoelectron microscopy as described previously (Marutani et al., 2004), except that the antibodies used were rabbit antibodies against either type I collagen or the N-propeptide of type I collagen α1 chain (LF-39).

RESULTS

Abnormal Fibril Formation of Type I Collagen by Hsp47-/- Cells

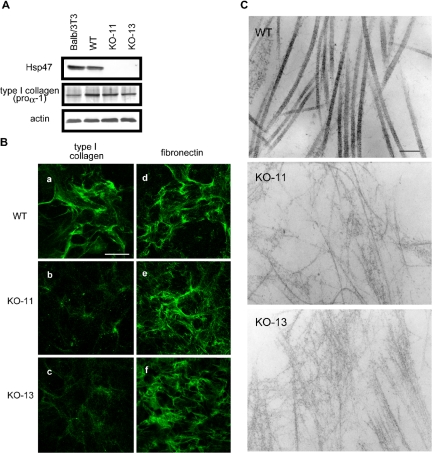

Previously, we established Hsp47-/- fibroblastic cell lines from the knockout embryos (Nagai et al., 2000) and showed that type I collagen secreted from these cells is susceptible to protease digestion. We extended these studies in the present investigation to determine whether the type I collagen secreted from Hsp47-/- fibroblasts can self-assemble into supramolecular fibrillar structures. Expression levels of type I collagen, determined by Western blotting of cell lysates, were similar between Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- fibroblasts except that Hsp47-/- KO-13 cells contained a slightly lower level of type I collagen (Figure 1A). Immunofluorescence staining of extracellular type I collagen, however, revealed that the staining patterns differed significantly between Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- cells (Figure 1B). Type I collagen fibrils secreted from Hsp47-/- cells were sparse and only very weakly stained compared with those produced by Hsp47+/+ cells. Detailed observation of collagen fibrils by electron microscopy further revealed that the thin type I collagen fibrils formed by Hsp47-/- cells frequently contained abnormal branches (Figure 1C). In contrast, the fibrils from Hsp47+/+ cells were thick and straight and had striated patterns. Fibronectin used as a control for an ECM component exhibited a normal pattern in both Hsp47-/- and Hsp47+/+ cells (Figure 1B), indicating that the effect of Hsp47 knockout was specific for collagen. These results indicated that the type I collagen secreted from Hsp47-/- fibroblasts was unable to form normal supramolecular fibrillar structures.

Figure 1.

Abnormal fibril formation of in Hsp47-/- cells. (A) Total soluble proteins in Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- cells and Balb/3T3 cells (control) were extracted and analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against type I collagen C-propeptide (LF-41), Hsp47, and actin (control). (B) Immunofluorescence staining of type I collagen (a-c) and fibronectin (d-f) secreted by Hsp47+/+ cell line (a and d) and Hsp47-/- cell lines KO-11 (b and e) and KO-13 (c and f). Staining was performed using specific antibody (AB765P) without permeabilization. Bar, 50 μm. (C) Electron microscopic observation of collagen fibrils secreted from Hsp47+/+ cells (a), Hsp47-/- KO-11 cells (b), and Hsp47-/- KO-13 cells (c). Bar, 200 nm.

Retardation of Type I Collagen Secretion and Its Accumulation in the ER

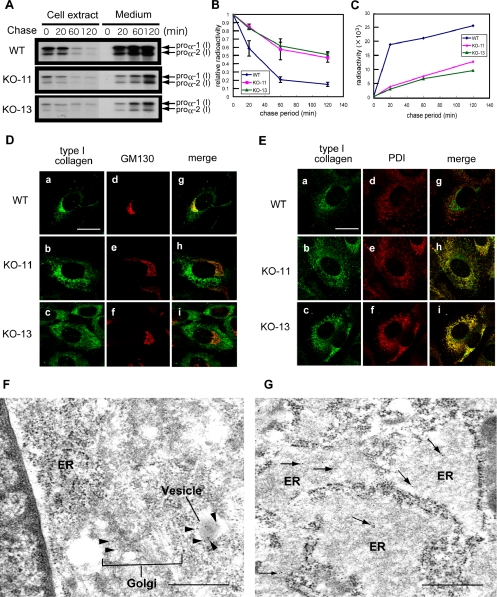

Secretion rate of type I collagen in Hsp47-/- fibroblasts was next examined by a pulse-label and -chase experiment followed by immunoprecipitation. Pulse-labeled intracellular type I collagen disappeared from Hsp47-/- fibroblasts four-fold more slowly than from Hsp47+/+ fibroblasts (Figure 2, A and B). Consistently, the pulse-labeled type I collagen was secreted into the culture medium from the Hsp47+/+ cells more rapidly than from the Hsp47-/- cells (Figure 2, A and C). The secretion rate of type I collagen in the Hsp47+/+ cells was similar to that of a previous study; the half-life of type I collagen in chick embryo fibroblasts was found to be ∼20 min (Satoh et al., 1996). Thus, these results indicated that the absence of Hsp47 retarded type I collagen secretion from fibroblasts. The next question is where this retardation of type I collagen occurred in the secretory pathway of Hsp47-/- fibroblasts. To determine the intracellular localization of type I collagen in Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- fibroblasts, we performed immunofluorescence staining using specific antibodies (Figure 2, D and E). In the Hsp47+/+ cells, a major portion of intracellular type I collagen was colocalized with GM130, a marker of cis-Golgi compartment (Perez et al., 2002). A minor portion was colocalized with PDI, a marker of ER (Mehtani et al., 1998), consistent with previous observations (Bonfanti et al., 1998). In contrast, type I collagen in Hsp47-/- cells was mostly colocalized with PDI, indicating that type I collagen is accumulated in the ER. The type I collagen staining in Hsp47-/- cells was distinct from the GM130 staining pattern. Immunoelectron microscopic analysis confirmed that type I collagen accumulated in markedly dilated ER of Hsp47-/- cells, whereas type I collagen was mainly observed in the Golgi apparatus or secretory granules of Hsp47+/+ cells (Figure 2, F and G). Thus, in Hsp47-/- cells, the lack of Hsp47 caused accumulation of type I collagen in the ER.

Figure 2.

Slow secretion of type I collagen and its accumulation in the ER in the absence of Hsp47. (A) Pulse-chase experiment of intracellular and extracellular type I collagen using Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- cells. Immunoprecipitation was performed with specific antibody (AB765P). (B) Relative radioactivity of pulse-labeled intracellular type I collagen during chase period. (C) Radioactivity of secreted type I collagen. WT, Hsp47+/+ cells. KO-11 and KO-13, Hsp47-/- cells. (D and E) Double immunofluorescence staining was performed using antibodies against type I collagen (AB765P) and GM130 (D) or PDI (E). (a, d, and g) Hsp47+/+ cells. (b, e, and h) Hsp47-/- KO-11 cells. (c, f, and i) Hsp47-/- KO-13 cells. Bar, 20 μm. (F and G) Immunoelectron microscopy of Hsp47+/+ (F) and Hsp47-/- (G) cells using primary antibody against type I collagen (AB765P) and secondary antibody labeled with gold particles. In F, black arrowheads indicate immunogold staining of type I collagen in the Golgi apparatus and a secretory granule, and white arrows show ER. Arrows in G indicate immunogold staining of type I collagen in dilated ER. Bar, 500 nm.

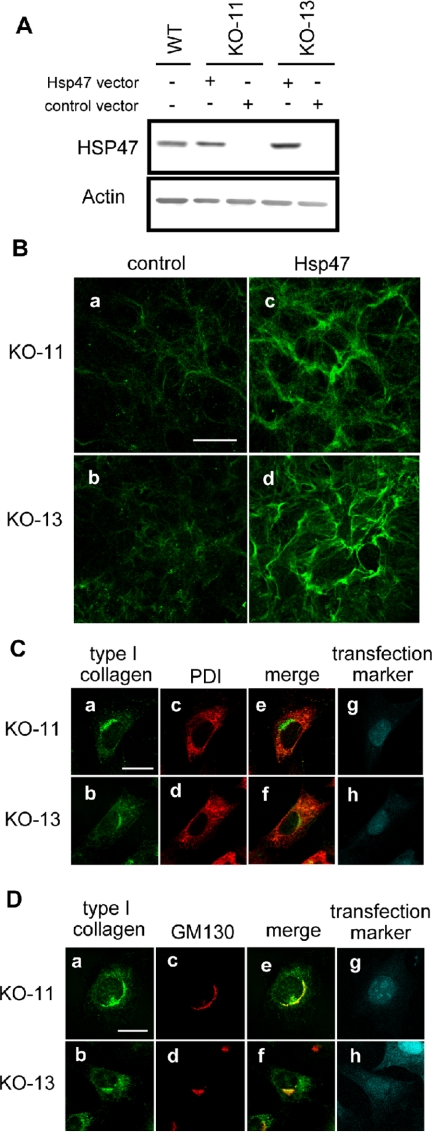

Transient Expression of Hsp47 in Hsp47-/- Cells Restores Normal Collagen Maturation

To confirm that the Hsp47 is the molecule responsible for type I collagen abnormalities observed in the Hsp47-/- cells, Hsp47 was transiently expressed in the Hsp47-/- cells and extracellular and intracellular distributions of type I collagen were examined by fluorescent microscopy. Transfection efficiency was ∼50% in the Hsp47-/- and Hsp47+/+ cells as determined by transfection of an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) vector (our unpublished data). After transfection, Hsp47 was clearly detected by the Western blotting in Hsp47-/- cells at the same level as in nontransfected Hsp47+/+ cells (Figure 3A). Extracellular type I collagen fibrils produced by Hsp47-transfected Hsp47-/- cells showed a strong and dense staining pattern, indistinguishable from that produced by Hsp47+/+ control cells (Figure 3B). In addition, type I collagen in Hsp47-/- cells transfected with Hsp47 cDNA colocalized mainly with GM130 (Figure 3D), rather than with PDI (Figure 3C), which is similar to wild-type fibroblasts. Thus, we conclude that the abnormal localization patterns are caused solely by the absence of Hsp47.

Figure 3.

Transient expression of Hsp47 in Hsp47-/- cells restores normal fibril formation and intracellular localization of type I collagen. (A) Transient Hsp47 expression in Hsp47-/- cells was analyzed by Western blotting after transfection of Hsp47 expression vector. (B) After transfection of mock vector (control) or Hsp47 expression vector (Hsp47), immunofluorescence staining of type I collagen was carried out without permeabilization. Bar, 50 μm. (C) Hsp47-transfected Hsp47-/- cells were analyzed by costaining of type I collagen and PDI. (a and b) Type I collagen. (c and d) PDI. (e and f) Merge. (g and h) mDsRed transfection marker. Bar, 20 μm. Note that staining signals were presented by pseudocolors. (D) Hsp47-transfected Hsp47-/- cells were analyzed by costaining of type I collagen and GM130. Bar, 20 μm. Antibodies used were the same as in Figures 1 and 2.

Solubility of Type I Collagen Is Affected by the Absence of Hsp47

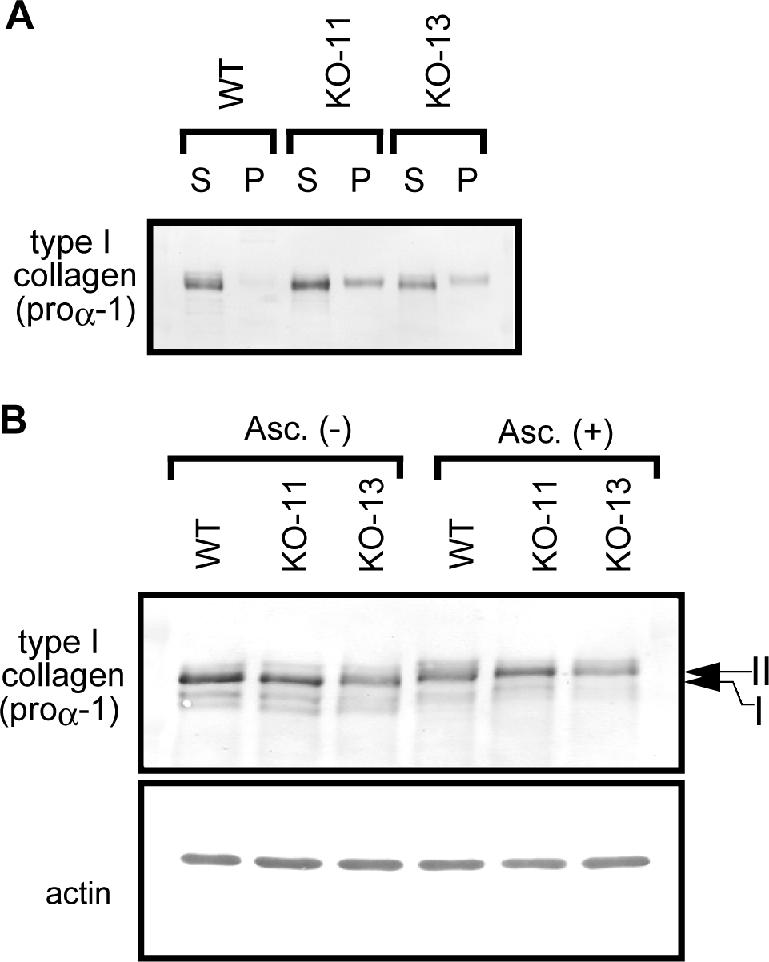

The accumulation of type I collagen in the ER of Hsp47-/- cells suggested that these cells may form aggregates of procollagen in the ER. Thus, we examined the soluble versus the insoluble fractions of type I collagen by centrifugal fractionation of cell lysates followed by Western blotting (Figure 4A). Intriguingly, considerable amounts of type I collagen were detected in the insoluble pellet fraction of Hsp47-/- cells, whereas none was detected in the pellet fraction of Hsp47+/+ cells. Because no significant level of pulse-labeled type I collagen was detected in the pellet fraction of Hsp47-/- cells during chase period up to 2 h (Supplemental Figure 1), the formation of insoluble type I collagen seems to be a slow process. Taking into account of intracellular localization of type I collagen (Figure 2, D-G), it suggests that a considerable portion of type I collagen is accumulated as aggregated forms in the ER of Hsp47-/- cells.

Figure 4.

Hydroxylated type I collagen forms NP-40-insoluble aggregate in Hsp47-/- fibroblasts. (A) Solubility of type I collagen in Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- cells was analyzed by centrifugal fractionation. Cell lysates of Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- cells were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, and supernatant (S) and pellet (P) were analyzed by immunoblotting with type I collagen C-propeptide antibody (LF-41). (B) Total soluble proteins extracted from Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- cells cultured with or without the addition of ascorbate were analyzed by Western blotting. Note that the mobility of type I collagen is slower in the presence of ascorbate (bands II) than the absence (band I).

Because the secretion rate of type I collagen was much slower in Hsp47-/- cells (Figure 2) and procollagen retention in the ER is known to be mediated by the P4H (Walmsley et al., 1999) and PDI (Wilson et al., 1998), we examined hydroxylation of type I collagen, which is dependent in the presence of ascorbic acid, a cofactor of P4H (Myllyharju, 2003). When compared between the presence and absence of ascorbate, the mobility of intracellular type I collagen in SDS-PAGE gels was significantly slower at the presence of ascorbate both in Hsp47+/+ and Hsp47-/- cells (Figure 4B). The mobility shift by ascorbate disappeared after treatment with α,α′-dipyridyl (Supplemental Figure 2), a specific inhibitor of P4H (Berg and Prockop, 1973a). Because collagen triple helices are known to be stabilized by proryl hydroxylation (Berg and Prockop, 1973b), this result clearly indicate that the inability of triple helix formation of type I procollagen in Hsp47-/- cells (Nagai et al., 2000) was not due to the insufficient hydroxylation of proline residues on procollagen.

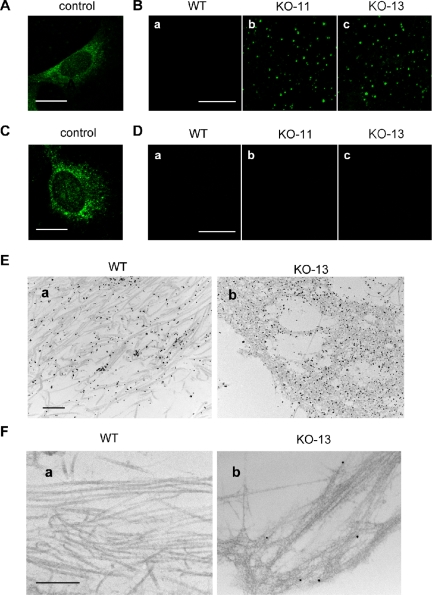

The Absence of Hsp47 Causes Accumulation of Unprocessed N-Propeptides in the ECM

In some collagen-related diseases, mutations on the triple helix domain of collagen prevent N-propeptide cleavage (Vogel et al., 1987, 1988). To investigate the processing of type I procollagen during secretion from Hsp47-/- cells, immunostaining of type I collagen N-propeptide and C-propeptide was carried out using specific antibodies. After cells were permeabilized with detergent, anti-N-propeptide and anti-C-propeptide antibodies stained intracellular procollagens that contained N- and C-propeptides, respectively (Figure 5, A and C). Although no staining of N-propeptide of type I collagen was observed in the extracellular regions of Hsp47+/+ cells, dot-like staining was unexpectedly observed in the ECM of Hsp47-/- cells with anti-N-propeptide antibody (Figure 5B). In contrast, no C-propeptide was detected in extracellular regions of Hsp47-/- or Hsp47+/+ cells, indicating that C-propeptide was cleaved even in the absence of Hsp47 (Figure 5D). This result was more clearly shown using immunoelectron microscopy (Figure 5, E and F). Antibody against whole type I collagen stained collagen fibrils that accumulated in the ECM whether they were formed by Hsp47+/+ cells or by Hsp47-/- cells (Figure 5E). In a marked contrast, type I collagen secreted from Hsp47-/- cells contained uncleaved N-propeptides along the thin and branched fibrils (Figure 5F, b), whereas anti-N-propeptide antibody did not stain the fibrils of Hsp47+/+ cells (Figure 5F, a). These results indicate that processing (cleavage) of N-propeptides of type I procollagen is impaired in Hsp47-/- cells, whereas that of C-propeptides is normal.

Figure 5.

Type I collagen containing unprocessed N-propeptide is secreted from Hsp47-/- cells. (A-D) Immunofluorescence staining was carried out with anti-type I collagen N-propeptide LF-39 antibody (A and B) or C-propeptide LF-41 antibody (C and D), with (A and C) or without (B and D) permeabilization. Bar, 20 μm (A and C) and 50 μm (B and D). (E and F) Immunoelectron microscopy was performed using anti-type I collagen AB765P antibody (E) or anti-N-propeptide LF-39 antibody (F), followed by incubation with secondary antibody labeled with gold particles. Bar, 500 nm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that type I collagen secreted from Hsp47-/- fibroblasts produced abnormally thin and sparse fibrils in the ECM and that these fibrils frequently showed branchlike structures by electron microscopy (Figure 1). Transient expression of Hsp47 cDNA in the Hsp47-/- cells restores normal phenotype in the fibril formation (Figure 3), indicating that the lack of Hsp47 causes severe defects in the fibrillogenesis of type I collagen. This observation suggests that the assembly processes of collagen molecules into fibrillar structures were severely affected by the presence of structurally abnormal molecules. We previously reported that the triple helix formation of types I and IV collagen is defective in the ER of Hsp47-/- cells because collagen secreted from Hsp47-/- cells is susceptible to protease digestion (Nagai et al., 2000; Matsuoka et al., 2004), and Hsp47 transiently associates with procollagen in the ER (Satoh et al., 1996). Thus, the improper triple helix of procollagen produced without the chaperone function of Hsp47 is likely to cause the defects in formation of collagen supramolecular structures.

We also demonstrated that secretion of type I collagen was significantly delayed in Hsp47-/- cells (Figure 2) as was the secretion of type IV collagen (Matsuoka et al., 2004). Consistent with delayed secretion, type I collagen was highly accumulated in the ER of Hsp47-/- cells, whereas the intracellular localization of type I collagen was observed mainly in the Golgi apparatus in Hsp47+/+ cells. A normal distribution pattern of type I collagen within the cells was restored by transient expression of Hsp47 in Hsp47-/- cells (Figure 3). Furthermore, we demonstrated that procollagen accumulates in the ER as insoluble aggregates in the absence of Hsp47 (Figure 4A). However, the delayed secretion seemed not to be the result of this aggregate formation because the aggregation was not observed within 2 h in pulse-chase experiments (Supplemental Figure 1). When the triple helix formation of procollagen is impaired by culturing the cells in the presence of α,α′-dipyridyl, an inhibitor of P4H, or in the absence of ascorbate, procollagen with improper triple helices is known to be retained in the ER, and the secretion rate is decreased (Juva et al., 1966; Satoh et al., 1996). Thus, the delayed secretion of procollagen in the absence of Hsp47 observed in the present study may be due to conformational abnormality of procollagen.

Hydroxylation of proline residues plays an important role for the triple helix formation of collagen. P4H hydroxylates proline residues on procollagen in the triple helix domain, particularly the proline at the Y position of Gly-X-Y repeats (Berg and Prockop, 1973b; van der Rest and Garrone, 1991), and this hydroxylation stabilizes triple helix (Bulleid et al., 1996). P4H is reported to associate with single α-chains of unfolded or incompletely folded procollagen (Walmsley et al., 1999). In the present study, however, hydroxylated procollagen was clearly detected in Hsp47-/- cells (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 2). Thus, improper triple helix formation observed in Hsp47-/- cells is not due to the insufficient prolyl-hydroxylation.

Triple helix formation proceeds from the C to the N terminus in a zipperlike manner (Bachinger et al., 1980; Engel and Prockop, 1991; Bulleid et al., 1997) after assembly of two α1-chains and one α2-chain at the C-propeptides. N- and C-propeptides are processed from the collagen helices during or immediately after secretion by N-proteinase ADAMTS-2 and C-proteinase BMP-1, respectively (Dombrowski and Prockop, 1988; Li et al., 1996). In the present study, we revealed for the first time that incompletely processed type I collagen containing N-propeptide was secreted from Hsp47-null fibroblasts and accumulated in the ECM (Figure 5). Because cleavage of N-propeptides does not occur until completion of the triple helix formation (Fessler and Fessler, 1979) and N-propeptide cleavage also fails to occur in heat denatured type I procollagen (Tuderman et al., 1978; Tuderman and Prockop, 1982; Hojima et al., 1989), the inability to cleave the N-propeptide of procollagen in Hsp47-/- cells is probably due to improper folding of type I collagen in the ER. Thus, this observation further supports the notion that Hsp47 is indispensable for proper triple helix formation of procollagen in the ER.

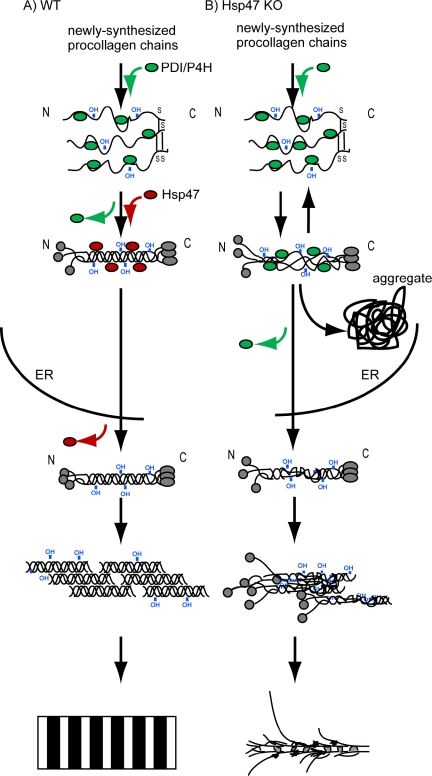

In contrast, C-propeptide cleavage, which is essential for the fibril formation (Peltonen et al., 1985), occurred normally in Hsp47-/- cells. Consistently, C-propeptide cleavage was reported to occur even though the triple helix of procollagen was destabilized by mutation (Vogel et al., 1987, 1988). C-propeptides assemble together before triple helix formation (Bachinger et al., 1980). Trimers of type I collagen α chains bridged by disulfide bonds at the C-propeptide region were detected in Hsp47-knockout fibroblasts using SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions (Supplemental Figure 3), indicating that Hsp47 does not affect the assembly of the C-propeptides of three α-chains of procollagen. Hsp47 binds to the triple helix form of procollagen in the ER, as shown previously in vivo, in vitro, and in semipermeabilized cells (Satoh et al., 1996; Koide et al., 2002; Tasab et al., 2002). Together, these observations suggest that Hsp47 is required in a process of triple helix formation of procollagen later than the C-propeptide assembly but earlier than N-propeptide cleavage (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Model for Hsp47 function in collagen maturation in vivo. (A) Wild-type cell. (B) Hsp47-knockout cell.

It is noteworthy that disease-causing mutations on the COL1 genes result in severe defects in collagen fibril formation (Kuivaniemi et al., 1991), including those that occurred in the N-terminal region of the α1 chain of type I collagen (Cabral et al., 2005). Dermal collagen fibrils in the patients with this mutation were significantly thinner than those of healthy controls, and cultured cells established from the patients were unable to cleave N-propeptides of type I procollagen. In studies of osteogenesis imperfecta, a point mutation in the N-terminal region of the triple helix of the α1 chain of type I collagen caused decreased cleavage of N-propeptide (Vogel et al., 1987, 1988). Although these observations are similar to the effect of the disruption of Hsp47 gene as shown here, they are clearly distinct in that the mutation in the collagen gene itself caused the improper folding, resulting in the impairment of N-propeptide processing. Thus, we revealed that the disruption of a molecular chaperone causes improper posttranslational processing of collagen molecules without any mutations in the collagen gene.

Our present data have shown that Hsp47 is required for the prevention of aggregate formation of procollagen in the ER and is indispensable for the formation of thick collagen fibrils with striated patterns. We can conceive two possible functions of Hsp47 as a collagen-specific molecular chaperone. Hsp47 may prevent the unfolding of the triple helix and thus stabilize it during the progression of procollagen folding (Nagai et al., 2000; Tasab et al., 2000), because Hsp47 preferentially binds to triple helix form of procollagen rather than the single α-chain (Koide et al., 2002; Tasab et al., 2002). Previous analysis of secreted collagen also supports the idea; the triple helix formation of procollagen was severely affected by the absence of Hsp47 as examined by protease digestion (Nagai et al., 2000; Matsuoka et al., 2004). This function of Hsp47 probably serves to prevent aggregation of misfolded procollagen in the ER, because procollagen was found to be accumulated as insoluble aggregates in the ER of Hsp47-/- cells.

The second possible function is to prevent the lateral association of procollagen triple helices in the ER. In vitro, collagen triple helices tend to associate each other and thus form collagen gels at neutral pH and room temperature. Thomson and Ananthanarayanan (2000) demonstrated that addition of Hsp47 prevents self-association of collagen triple helices in vitro. Whereas it is not proven whether this mechanism also works in the ER, there is a supportive evidence that procollagen molecules laterally associate in the Golgi apparatus (Bonfanti et al., 1998) where procollagen is liberated from Hsp47 (Satoh et al., 1996). In the present study, however, fibrillar structure of type I procollagen was not observed in the ER of Hsp47-/- cells, whereas detergent-insoluble aggregates of procollagen accumulated in dilated ERs. Because this may due to the absence of properly folded procollagen triple helices in the ER of Hsp47-/- cells, our results cannot completely exclude the possibility that Hsp47 functions in preventing the formation of large supramolecular structures of triple helical procollagen in the ER. Thus, it is possible that Hsp47 works as a collagen-specific molecular chaperone both in facilitating the triple helix formation and in preventing the lateral association in the ER.

In summary, we demonstrated for the first time in the present study that Hsp47 facilitates productive folding of procollagen with preventing its aggregation in the ER. This function of Hsp47 is indispensable for the effective secretion of procollagen from the ER-to-Golgi apparatus and the processing of N-propeptide leading to the fibril formation in the ECM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Larry W. Fisher for providing antibodies to type I collagen N- and C-propeptide (LF-39 and LF-41) and Dr. Lynn Y. Sakai for assistance with electron microscopy. We also thank Dr. Yasuhiro Matsuoka for helpful suggestions.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1065) on March 8, 2006.

Abbreviations used: ECM, extracellular matrix; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Hsp47, heat-shock protein of 47 kDa; P4H, prolyl 4-hydroxylase.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Bachinger, H. P., Bruckner, P., Timpl, R., Prockop, D. J., and Engel, J. (1980). Folding mechanism of the triple helix in type-III collagen and type-III pN-collagen. Role of disulfide bridges and peptide bond isomerization. Eur. J. Biochem. 106, 619-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, R. A., and Prockop, D. J. (1973a). Purification of (14C) protocollagen and its hydroxylation by prolyl-hydroxylase. Biochemistry 12, 3395-3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, R. A., and Prockop, D. J. (1973b). The thermal transition of a nonhydroxylated form of collagen. Evidence for a role for hydroxyproline in stabilizing the triple-helix of collagen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 52, 115-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti, L., Mironov, A. A., Jr., Martinez-Menarguez, J. A., Martella, O., Fusella, A., Baldassarre, M., Buccione, R., Geuze, H. J., Mironov, A. A., and Luini, A. (1998). Procollagen traverses the Golgi stack without leaving the lumen of cisternae: evidence for cisternal maturation. Cell 95, 993-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot-Handford, R. P., Tuckwell, D. S., Plumb, D. A., Rock, C. F., and Poulsom, R. (2003). A novel and highly conserved collagen (pro(alpha)1(XXVII)) with a unique expression pattern and unusual molecular characteristics establishes a new clade within the vertebrate fibrillar collagen family. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31067-31077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottomley, M. J., Batten, M. R., Lumb, R. A., and Bulleid, N. J. (2001). Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum: PDI mediates the ER retention of unassembled procollagen C-propeptides. Curr. Biol. 11, 1114-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulleid, N. J., Dalley, J. A., and Lees, J. F. (1997). The C-propeptide domain of procollagen can be replaced with a transmembrane domain without affecting trimer formation or collagen triple helix folding during biosynthesis. EMBO J. 16, 6694-6701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulleid, N. J., Wilson, R., and Lees, J. F. (1996). Type-III procollagen assembly in semi-intact cells: chain association, nucleation and triple-helix folding do not require formation of inter-chain disulphide bonds but triple-helix nucleation does require hydroxylation. Biochem. J. 317, 195-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, W. A., Makareeva, E., Colige, A., Letocha, A. D., Ty, J. M., Yeowell, H. N., Pals, G., Leikin, S., and Marini, J. C. (2005). Mutations near amino end of alpha1(I) collagen cause combined osteogenesis imperfecta/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome by interference with N-propeptide processing. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19259-19269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessler, S. D., and Byers, P. H. (1993). BiP binds type I procollagen pro alpha chains with mutations in the carboxyl-terminal propeptide synthesized by cells from patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 18226-18233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski, K. E., and Prockop, D. J. (1988). Cleavage of type I and type II procollagens by type I/II procollagen N-proteinase. Correlation of kinetic constants with the predicted conformations of procollagen substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 16545-16552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J., and Prockop, D. J. (1991). The zipper-like folding of collagen triple helices and the effects of mutations that disrupt the zipper. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 20, 137-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, L. R., Norris, K., Smith, T., Hebert, C., and Sauk, J. J. (1994). Association of Hsp47, Grp78, and Grp94 with procollagen supports the successive or coupled action of molecular chaperones. J. Cell. Biochem. 56, 518-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessler, L. I., and Fessler, J. H. (1979). Characterization of type III procollagen from chick embryo blood vessels. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 233-239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, L. W., Stubbs, J. T., 3rd, and Young, M. F. (1995). Antisera and cDNA probes to human and certain animal model bone matrix noncollagenous proteins. Acta Orthop. Scand. Suppl. 266, 61-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojima, Y., McKenzie, J. A., van der Rest, M., and Prockop, D. J. (1989). Type I procollagen N-proteinase from chick embryo tendons. Purification of a new 500-kDa form of the enzyme and identification of the catalytically active polypeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 11336-11345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulmes, D. J. (2002). Building collagen molecules, fibrils, and suprafibrillar structures. J. Struct. Biol. 137, 2-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juva, K., Prockop, D. J., Cooper, G. W., and Lash, J. W. (1966). Hydroxylation of proline and the intracellular accumulation of a polypeptide precursor of collagen. Science 152, 92-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide, T., Takahara, Y., Asada, S., and Nagata, K. (2002). Xaa-Arg-Gly triplets in the collagen triple helix are dominant binding sites for the molecular chaperone HSP47. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6178-6182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuivaniemi, H., Tromp, G., and Prockop, D. J. (1991). Mutations in collagen genes: causes of rare and some common diseases in humans. FASEB J. 5, 2052-2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamande, S. R., Chessler, S. D., Golub, S. B., Byers, P. H., Chan, D., Cole, W. G., Sillence, D. O., and Bateman, J. F. (1995). Endoplasmic reticulum-mediated quality control of type I collagen production by cells from osteogenesis imperfecta patients with mutations in the pro alpha 1 (I) chain carboxyl-terminal propeptide which impair subunit assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 8642-8649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. W., Sieron, A. L., Fertala, A., Hojima, Y., Arnold, W. V., and Prockop, D. J. (1996). The C-proteinase that processes procollagens to fibrillar collagens is identical to the protein previously identified as bone morphogenic protein-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 5127-5130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marutani, T., Yamamoto, A., Nagai, N., Kubota, H., and Nagata, K. (2004). Accumulation of type IV collagen in dilated ER leads to apoptosis in Hsp47-knockout mouse embryos via induction of CHOP. J. Cell Sci. 117, 5913-5922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, Y., Kubota, H., Adachi, E., Nagai, N., Marutani, T., Hosokawa, N., and Nagata, K. (2004). Insufficient folding of type IV collagen and formation of abnormal basement membrane-like structure in embryoid bodies derived from Hsp47-null embryonic stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 4467-4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehtani, S., Gong, Q., Panella, J., Subbiah, S., Peffley, D. M., and Frankfater, A. (1998). In vivo expression of an alternatively spliced human tumor message that encodes a truncated form of cathepsin B. Subcellular distribution of the truncated enzyme in COS cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13236-13244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllyharju, J. (2003). Prolyl 4-hydroxylases, the key enzymes of collagen biosynthesis. Matrix Biol. 22, 15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllyharju, J., and Kivirikko, K. I. (2004). Collagens, modifying enzymes and their mutations in humans, flies and worms. Trends Genet. 20, 33-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, N., Hosokawa, M., Itohara, S., Adachi, E., Matsushita, T., Hosokawa, N., and Nagata, K. (2000). Embryonic lethality of molecular chaperone hsp47 knockout mice is associated with defects in collagen biosynthesis. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1499-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, K. (2003). HSP47 as a collagen-specific molecular chaperone: function and expression in normal mouse development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 14, 275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, K., Saga, S., and Yamada, K. M. (1986). A major collagen-binding protein of chick embryo fibroblasts is a novel heat shock protein. J. Cell Biol. 103, 223-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltonen, L., Halila, R., and Ryhanen, L. (1985). Enzymes converting procollagens to collagens. J. Cell. Biochem. 28, 15-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez, F., Pernet-Gallay, K., Nizak, C., Goodson, H. V., Kreis, T. E., and Goud, B. (2002). CLIPR-59, a new trans-Golgi/TGN cytoplasmic linker protein belonging to the CLIP-170 family. J. Cell Biol. 156, 631-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop, D. J., and Kivirikko, K. I. (1995). Collagens: molecular biology, diseases, and potentials for therapy. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 403-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga, S., Nagata, K., Chen, W. T., and Yamada, K. M. (1987). pH-dependent function, purification, and intracellular location of a major collagen-binding glycoprotein. J. Cell Biol. 105, 517-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh, M., Hirayoshi, K., Yokota, S., Hosokawa, N., and Nagata, K. (1996). Intracellular interaction of collagen-specific stress protein HSP47 with newly synthesized procollagen. J. Cell Biol. 133, 469-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasab, M., Batten, M. R., and Bulleid, N. J. (2000). Hsp 47, a molecular chaperone that interacts with and stabilizes correctly-folded procollagen. EMBO J. 19, 2204-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasab, M., Jenkinson, L., and Bulleid, N. J. (2002). Sequence-specific recognition of collagen triple helices by the collagen-specific molecular chaperone HSP47. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35007-35012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, C. A., and Ananthanarayanan, V. S. (2000). Structure-function studies on hsp 47, pH-dependent inhibition of collagen fibril formation in vitro. Biochem. J. 349 Pt 3, 877-883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuderman, L., Kivirikko, K. I., and Prockop, D. J. (1978). Partial purification and characterization of a neutral protease which cleaves the N-terminal propeptides from procollagen. Biochemistry 17, 2948-2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuderman, L., and Prockop, D. J. (1982). Procollagen N-proteinase. Properties of the enzyme purified from chick embryo tendons. Eur. J. Biochem. 125, 545-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Rest, M., and Garrone, R. (1991). Collagen family of proteins. FASEB J. 5, 2814-2823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, B. E., Doelz, R., Kadler, K. E., Hojima, Y., Engel, J., and Prockop, D. J. (1988). A substitution of cysteine for glycine 748 of the alpha 1 chain produces a kink at this site in the procollagen I molecule and an altered N-proteinase cleavage site over 225 nm away. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 19249-19255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, B. E., Minor, R. R., Freund, M., and Prockop, D. J. (1987). A point mutation in a type I procollagen gene converts glycine 748 of the alpha 1 chain to cysteine and destabilizes the triple helix in a lethal variant of osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 14737-14744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley, A. R., Batten, M. R., Lad, U., and Bulleid, N. J. (1999). Intracellular retention of procollagen within the endoplasmic reticulum is mediated by prolyl 4-hydroxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14884-14892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R., Lees, J. F., and Bulleid, N. J. (1998). Protein disulfide isomerase acts as a molecular chaperone during the assembly of procollagen. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9637-9643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.