Abstract

Objectives. This study evaluated 1995 guidelines for HIV testing of pregnant women.

Methods. Analysis focused on Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data for the years 1994 through 1999. Data were aggregated across states.

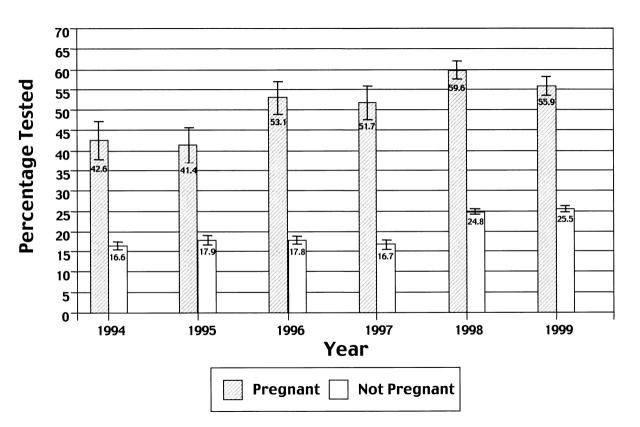

Results. Percentages of pregnant women tested for HIV increased from 1995 to 1996 (from 41% to 53%) and again from 1997 (52%) to 1998 (60%).

Conclusions. After implementation of the guidelines, the percentage of pregnant women tested for HIV increased, although nearly half had not been tested. More efforts are needed to encourage women to undergo testing for HIV during pregnancy, thus maximizing opportunities for offering antiretroviral therapy.

In 1994, the US Public Health Service (PHS) recommended the use of zidovudine during pregnancy to prevent the perinatal transmission of HIV infection.1 The 1995 PHS guidelines for the counseling and voluntary testing of pregnant women included recommendations that all pregnant women be counseled and encouraged to undergo testing for HIV infection and that testing be voluntary.2 In October 1998, the Institute of Medicine issued a report recommending a national policy of universal testing, with patient notification, as a routine component of prenatal care.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics supported the Institute of Medicine recommendation.4 Our objective was to evaluate the implementation of the 1995 PHS guidelines for HIV counseling and testing of pregnant women.

METHODS

We analyzed data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) for the years 1994 through 1999. In each state, data are collected monthly through telephone interviews conducted with a random sample of adults 18 years or older.5 The BRFSS has been approved by institutional review boards in each state; participants provide oral consent to be interviewed.

We defined testing as self-report of an HIV test within 12 months before the interview. For the years 1994 through 1997, we determined testing with the question “When was your last HIV test?” In 1998 and 1999, the question was changed to ask “Have you been tested for HIV in the past 12 months?” Pregnancy was determined via the question “To your knowledge, are you now pregnant?”

We restricted the sample to women aged 18 to 44 years. Data were weighted and aggregated across states for each year to obtain national estimates. Analyses were conducted with SUDAAN software (release 7.5.2; Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to account for the complex survey design. Annual prevalence estimates (percentages) were calculated for each variable. Using multiple logistic regression analyses, we determined the effect of demographic and health care variables on HIV testing among pregnant women only.

RESULTS

During each year, the sample comprised more than 30 000 women. Most characteristics did not change over time; a majority of the women were White (range: 70%–76%), were married (56%–58%), had completed high school (89%–90%), were employed (74%–77%), had health insurance (81%–84%), and had ever undergone a Papanicolaou test (92%–93%). The percentage of women who were pregnant did not change from 1994 to 1999 (range: 4.4%–5.1%).

The percentage of pregnant women tested for HIV increased from 1994 to 1996 and then again from 1997 to 1998 (Figure 1 ▶). The percentage of pregnant women tested was consistently higher than the percentage of nonpregnant women tested (Figure 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Percentages of women tested for HIV, by pregnancy status and year of interview: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1994–1999.

Pregnant women were more likely to be tested if they lived in the South, were not working, were aged 18 to 24 years, had never been married, or had health insurance (Table 1 ▶). They were less likely to be tested if they had had a Papanicolaou test more than 12 months before the interview or had never had a Papanicolaou test.

TABLE 1—

Logistic Regression Results: HIV Testing Among Pregnant Women, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1994–1999

| Sample (n = 9159) | ||||

| No. | % (SE) | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 1467 | 18.50 (0.64) | 0.9 | 0.7, 1.2 |

| Midwest | 2269 | 23.49 (0.65) | 1.0 | 0.8, 1.3 |

| South | 2912 | 33.77 (0.75) | 2.1 | 1.7, 2.6 |

| West | 2511 | 24.23 (0.77) | Reference | |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed/student | 5933 | 62.15 (0.83) | 1.2 | 1.0, 1.4 |

| Not working | 1007 | 12.70 (0.59) | 1.8 | 1.4, 2.5 |

| Homemaker | 2183 | 25.16 (0.75) | Reference | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18–24 | 2558 | 31.38 (0.81) | 1.9 | 1.5, 2.5 |

| 25–34 | 5163 | 54.54 (0.83) | 1.4 | 1.2, 1.7 |

| 35–44 | 1438 | 14.08 (0.53) | Reference | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 1344 | 15.37 (0.62) | 1.6 | 1.3, 2.1 |

| Previously married | 604 | 5.47 (0.35) | 1.7 | 1.2, 2.3 |

| Unmarried couple | 415 | 5.09 (0.40) | 1.3 | 0.9, 2.0 |

| Married | 6787 | 74.06 (0.74) | Reference | |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Yes | 8269 | 88.95 (0.57) | 1.5 | 1.2, 2.0 |

| No | 883 | 11.05 (0.57) | Reference | |

| Papanicolaou test history | ||||

| Never | 172 | 2.98 (0.32) | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.5 |

| More than 12 months since test | 548 | 5.85 (0.40) | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.5 |

| Within past 12 months | 8395 | 91.17 (0.50) | Reference | |

| Year of interview | ||||

| 1994 | 1210 | 16.67 (0.67) | 1.0 | 0.8, 1.3 |

| 1995a | 1473 | 16.99 (0.64) | Reference | |

| 1996 | 1390 | 15.51 (0.58) | 1.7 | 1.3, 2.1 |

| 1997 | 1448 | 15.96 (0.57) | 1.6 | 1.2, 2.0 |

| 1998 | 1753 | 17.26 (0.59) | 2.3 | 1.8, 3.0 |

| 1999 | 1885 | 17.62 (0.60) | 1.9 | 1.5, 2.4 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 6893 | 69.14 (0.83) | Reference | |

| Black | 894 | 10.19 (0.47) | 1.2 | 0.9, 1.6 |

| Hispanic | 901 | 15.82 (0.72) | 1.0 | 0.8, 1.3 |

| Other | 455 | 4.84 (0.43) | 0.8 | 0.6, 1.3 |

| Income, $ | ||||

| <10 000 | 581 | 8.86 (0.60) | 0.8 | 0.6, 1.2 |

| 10 000–19 999 | 1200 | 15.14 (0.65) | 0.9 | 0.7, 1.2 |

| 20 000–34 999 | 2408 | 28.32 (0.80) | 0.9 | 0.8, 1.1 |

| ≥35 000 | 3962 | 47.68 (0.87) | Reference | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 887 | 13.48 (0.65) | 1.4 | 1.0, 1.9 |

| High school | 2701 | 29.77 (0.76) | 1.2 | 1.0, 1.5 |

| Some college | 2760 | 28.04 (0.74) | 1.2 | 1.0, 1.4 |

| College | 2807 | 28.71 (0.71) | Reference | |

Note. The sample size is unweighted. Percentages and standard errors were calculated from weighted data. Odds ratios were adjusted for all other variables in the model. Sample sizes may not sum to total owing to missing data; percentages may not sum to 100 owing to rounding.

aChosen as the reference year because it was the year the counseling and testing guidelines were implemented.

DISCUSSION

HIV testing among pregnant women in the BRFSS increased after implementation of the 1995 PHS guidelines, from 41% in 1995 to 56% in 1999. During that time, the rate of testing among nonpregnant women remained fairly stable, suggesting that the guidelines had an effect. Despite these increases, the percentage of pregnant women tested was just over 50%, suggesting that more efforts are needed to encourage women to be tested for HIV during pregnancy. This will maximize opportunities to offer antiretroviral therapy, thereby reducing the risk of perinatal HIV transmission. In addition, women found to be HIV infected will benefit from antiretroviral therapy for their own health.

The percentage of pregnant women in our sample who reported having been tested for HIV was lower than in several studies of women recruited in prenatal clinics, each of which reported percentages above 70%.6–8 Similarly, in a population-based sample of postpartum women in several states, 58% to 81% of those interviewed in 1996 and 1997 recalled having been tested for HIV during pregnancy.9 The BRFSS interview does not include a question asking whether a test was offered or refused; therefore, we do not know the extent to which our lower rate of testing may have resulted from inclusion of women who were not offered a test or who refused.

Younger age, not being married or employed, living in the South, and having health insurance were associated with having been tested for HIV. Findings regarding demographic correlates of acceptance or refusal of testing have been mixed; for example, race/ethnicity has been associated with refusal in some studies10,11 but not in others,6,12 and younger age (i.e., less than 25 years) has been associated with testing in several studies.9,11,12 Regional differences in testing prevalence rates may be influenced by differences in state legislation regarding the counseling and testing of pregnant women.9 HIV/AIDS seroprevalence may also affect testing; of the 4 regions, the South accounts for the largest number and proportion of AIDS cases.13

Because the BRFSS relies on self-reported data, a degree of bias in testing behaviors is expected. Women who reported having been tested could have assumed that HIV testing was part of a routine battery of prenatal tests, and some of the women may have forgotten that they had undergone an HIV test during pregnancy.

In addition, there may have been some misclassification of testing during pregnancy: women who were pregnant at the time of the interview may not have been pregnant at the time of the test, and vice versa. If an equal proportion of women were misclassified in each group, then there would be no effect on the relative prevalence of testing. The change in the testing question in 1998 may have contributed to the increase in testing relative to earlier years; some women may have reported that they were tested within the past 12 months when, in fact, it had been more than 12 months since they were tested.

Monitoring of HIV testing among pregnant women will continue to be important to recognizing changes in the prevalence of testing. These data are useful, along with those from HIV/AIDS surveillance, in assessing the effect of new policies or guidelines such as the Institute of Medicine's recommendation for universal HIV testing as a routine component of prenatal care.5

Acknowledgments

The contribution of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System staff in each state is gratefully acknowledged.

At the time of this study, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System was considered exempt by the institutional review board of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A. Lansky, J. L. Jones, and M. L. Lindegren planned the study and interpreted the data. R. L. Frey analyzed the data. A. Lansky wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the work, made suggestions, and contributed editorially to the paper.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations of the US Public Health Service Task Force on the use of zidovudine to reduce perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43(RR-11):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Public Health Service recommendations for human immunodeficiency virus counseling and voluntary testing for pregnant women. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44(RR-7):1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Reducing the Odds: Preventing Perinatal Transmission of HIV in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed]

- 4.Human immunodeficiency virus screening. Joint statement of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pediatrics. 1999;104:128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State- and sex-specific prevalence of selected characteristics—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1996 and 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49(SS-6):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong VK, Silebi M. HIV testing of pregnant women: risk factors. In: Program and abstracts of the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; September 15–18, 1996; Chicago, Ill. Abstract I44.

- 7.Carusi D, Learman LA, Posner SF. Human immunodeficiency virus test refusal in pregnancy: a challenge to voluntary testing. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivero Y, Fernandez MI, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. Effect of name reporting on HIV testing rates among women in prenatal care in Miami. In: Program and abstracts of the XII International Conference on AIDS; June 28–July 2, 1998; Geneva, Switzerland. Abstract 43129.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prenatal discussion of HIV testing and maternal HIV testing—14 states, 1996–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hight EB, Bond A. HIV counseling and testing in high risk prenatal patients. In: Program and abstracts of the National Conference on Women and HIV; May 4–7, 1997; Los Angeles, Calif. Abstract 225.4.

- 11.Sorin MD, Tesoriero JM, LaChance-McCullough ML. Correlates of acceptance of HIV testing and post-test counseling in the obstetrical setting. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8:72–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webber MP, Schoenbaum EE, Bonuck KA. Correlates of voluntary human immunodeficiency virus testing reported by postpartum women. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1997;52:89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999:1–43.