Approximately 13% of pregnant women in the United States smoke,1 with serious health consequences for themselves and their infants.2–7 However, many women make important changes in health behavior when pregnant and approximately 30% of women smokers quit spontaneously early in their pregnancies.8 In June 2000, the US surgeon general released clinical practice guidelines for smoking cessation programs and recommended that “because of the serious risks of smoking to the pregnant smoker and fetus, whenever possible pregnant smokers should be offered extended or augmented psychosocial interventions that exceed minimal advice to quit.”9 Minimal contact interventions also have been shown to have some benefit for pregnant smokers and their offspring.10–14

We surveyed coverage of prenatal tobacco dependence treatments in health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in California to assess the availability, accessibility, use, and effectiveness of services offered to pregnant smokers. The survey addressed the following services: individual, group, and telephone counseling and self-help kits. The eligible sample included 39 full-service HMOs, all of which responded to the survey. For each HMO, we identified the most knowledgeable staff member to answer the survey.

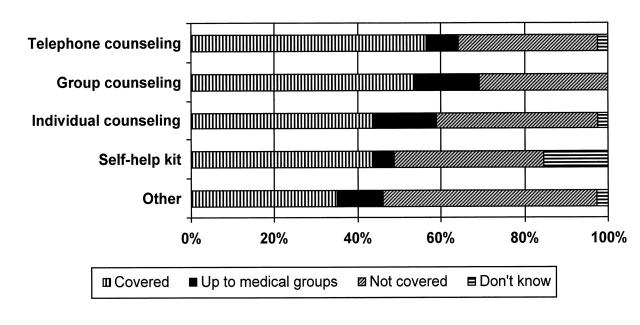

Only 3 HMOs (8%) covered all 4 services. Thirty-six HMOs (92%) covered at least 1 treatment, whereas 3 (8%) covered no tobacco dependence treatments for pregnant women. Seventeen HMOs (44%) reported covering at least 1 additional smoking cessation service, such as nicotine replacement therapy, for pregnant women beyond those about which we asked. Coverage ranged from a low of 44% for self-help kits and individual counseling to a high of 56% for telephone counseling (Figure 1 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Coverage of prenatal smoking cessation services among California health maintenance organizations (N = 39).

In many cases, HMOs delegated decisions about provision of treatments to the medical groups with which they contract. Among HMOs covering each service, prior authorization requirements for coverage were low. Specialty training requirements were highest for group counseling (57%) and lowest for staff providing self-help kits (18%). Thirteen HMOs (33%) reported having established memoranda of understanding or contractual relationships with other organizations to provide tobacco dependence treatment services to their members.

Of the HMOs covering services, only 67% monitored utilization (e.g., keeping lists of participants). Only 28% of these HMOs monitored quit rates among pregnant smokers. Thirty-two of the 39 HMOs (82%) reported that their providers screen all pregnant women for smoking, whereas 7 HMOs (18%) did not know whether screening took place.

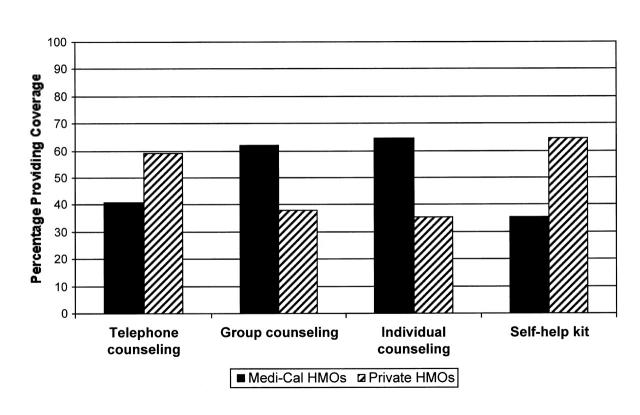

Medi-Cal managed care plans were more likely to provide coverage for face-to-face services (individual and group counseling) compared with commercial HMOs (Figure 1 ▶). In California, members of Medi-Cal managed care plans may have better access to the most effective, clinically intensive tobacco dependence treatment services, because providers of Medi-Cal managed care are mandated to identify and intervene on risk conditions identified during pregnancy.

Our findings suggest that in 1997, most California HMOs were not covering the extended or augmented psychosocial interventions that have been recommended for all pregnant smokers by the US Public Health Service.9,15 Although managed care offers the potential for increasing the availability and accessibility of such services for plan members, this survey suggests that that potential is not being realized. In addition, many California HMOs are unable to judge the use or effectiveness of these services and can neither track the costs and benefits of existing programs nor determine the need for additional services.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted by the Maternal, Child and Adolescent Nutrition Leadership Program at the University of California, Berkeley, funded by grant 5MCJ-069180 from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau.

Peer Reviewed

K. E. Pickett wrote the paper and conducted analyses. B. Abrams was the principal investigator and conceived the study. B. Abrams, H. H. Schauffler, J. Savage, P. Brandt, and S. A. Chapman designed the survey. P. Brandt conducted the survey. A. Kalkbrenner conducted analyses. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of several drafts.

References

- 1.Ebrahim SH, Floyd RL, Merritt RK, Decoufle P, Holtzman D. Trends in pregnancy-related smoking rates in the United States, 1987–1996. JAMA. 2000;283:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh RA. Effects of maternal smoking on adverse pregnancy outcomes: examination of the criteria of causation. Hum Biol. 1994;66:1059–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiFranza JR, Lew RA. Effect of maternal cigarette smoking on pregnancy complications and sudden infant death syndrome. J Fam Pract. 1995;40:385–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tager IB, Ngo L, Hanrahan JP. Maternal smoking during pregnancy: effects on lung function during the first 18 months of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:977–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor B, Wadsworth J. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and lower respiratory tract illness in early life. Arch Dis Child. 1987;62:786–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brook JS, Brook DW, Whiteman M. The influence of maternal smoking during pregnancy on the toddler's negativity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:381–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakschlag LS, Leventhal BL, Cook E, Pickett KE. Intergenerational health consequences of maternal smoking. Econ Neurosci. 2000;2:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: Office on Smoking and Health, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1990.

- 9.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Rockville, Md: Public Health Service; June 2000. Clinical Practice Guideline.

- 10.Windsor RA, Woodby LL, Miller TM, Hardin JM, Crawford MA, DiClemente CC. Effectiveness of Agency for Health Care Policy and Research clinical practice guideline and patient education methods for pregnant smokers in Medicaid maternity care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ershoff DH, Mullen PD, Quinn VP. A randomized trial of a serialized self-help smoking cessation program for pregnant women in an HMO. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh RA, Redman S, Brinsmead MW, Byrne JM, Melmeth A. A smoking cessation program at a public antenatal clinic. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1201–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Windsor RA, Cutter G, Morris J, et al. The effectiveness of smoking cessation methods for smokers in public health maternity clinics: a randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:1389–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Windsor RA, Lowe JB, Perkins LL, et al. Health education for pregnant smokers: its behavioral impact and cost benefit. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:201–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiore M, Bailey W, Cohen S, et al. Smoking Cessation. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1996. Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 18.