Abstract

The pandemic of HIV/AIDS continues to pose a serious threat to the population of sub-Saharan Africa, despite ongoing public health efforts to control the spread of infection. Given the important role of oral tradition in indigenous settings throughout rural Africa, we are beginning an innovative approach to HIV/AIDS prevention based on the use of folk media.

This commentary explains the types of folk media used in the traditional Ghanaian setting and explores their consistency with well-known theories. Folk media will be integrated with broadcast radio for interventions under the HIV/AIDS Behavior Change Communication Project being undertaken as part of the CARE–CDC Health Initiative (CCHI) in 2 districts in Ghana.

Nowhere has the impact of HIV/ AIDS been more severe than Sub-Saharan Africa. All but unknown a generation ago, today it poses the foremost threat to development in the region. By any measure and at all levels, its impact is simply staggering…

Leslie Casely-Hayford1

THE PROBLEM OF HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in eastern and southern African countries such as Uganda, Botswana, and South Africa, is well known. Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rate of infection among adults and children in the world. Ninety-five percent of all people infected by HIV live in developing countries, and more than 70% of the total HIV-infected population lives in sub-Saharan Africa. Eighty-four percent of those who have died of HIV/ AIDS since the beginning of the epidemic resided in sub-Saharan Africa, and 90% of children infected by HIV through mother-to-child transmission are in sub-Saharan Africa.1

In response to this epidemic, enormous resources have been committed to fighting the disease throughout the world. Ghana, which recognizes the macro and micro effects of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, is taking steps to prevent the devastating impact currently experienced in other parts of Africa. Despite these efforts, the reported number of HIV/ AIDS cases in Ghana continues to rise. One reliable preventive measure has been the adoption of “positive reproductive health lifestyles,” such as abstinence from sex, faithfulness to one's partner, and the use of condoms. To augment existing prevention programs, the CARE–CDC Health Initiative (CCHI) project in 2 districts in Ghana is exploring the use of traditional folk media in preventing HIV/AIDS.

BACKGROUND

CARE International introduced broad reproductive health initiatives in the Wassa West and Adansi West districts of Ghana in 1996 and 1999, respectively. The Wassa West Reproductive Health Project, located in western Ghana, has the overall goal of assisting residents in the Wassa West district to achieve their reproductive health aims by complementing existing efforts to encourage family planning and to reduce the transmission of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). The Ashanti Region Community Health (ARCH) Project, located in the Adansi West district of Ghana, is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the US Agency for International Development. It provides services aimed at improving the household and health security of the district's population by promoting “safer sex,” that is, sex that is free from unwanted pregnancy, unplanned birth spacing, disease (STDs and HIV/AIDS), and sexual abuse.

The residents of both districts are predominantly illiterate or low-literate Akan-speaking people whose main occupation is either mining or farming. These characteristics make most health communication strategies almost alien to the population. High-risk reproductive health behaviors are common in both districts, because of the influx of migrant workers who have disposable incomes. The indigenous culture is largely based on oral histories and traditions, much of which remains unwritten. Consequently, some of the information presented here derives from our personal experiences of being raised and living among people in rural Ghana. Working with orally based cultures, as Walter Ong has stated, requires conscious efforts to address the cognitive mindset of audiences who are primarily listeners and speakers rather than readers and writers.2 We are exploring the application of more indigenous audiovisual and interactive communication methods, especially the use of folk media. We believe this approach will be effective in Ghana because it embodies many of the activities, beliefs, and customs of the local population's own way of life.

WHAT ARE FOLK MEDIA?

Folk media have various descriptors. The terms “oramedia,” “traditional media,” and “informal media” have often been used interchangeably in referring to folk media. Ansu-Kyeremeh defines folk media as “any form of endogenous communication system which by virtue of its origin from, and integration into a specific culture, serves as a channel for messages in a way and manner that requires the utilization of the values, symbols, institutions, and ethos of the host culture through its unique qualities and attributes.”3(p3) Folk media are often used for personal as well as group information sharing and discussion and draw their popularity from their entertaining nature. Types of folk media include storytelling, puppetry, proverbs, visual art, drama, role-play, concerts, gong beating, dirges, songs, drumming, and dancing.

Ansu-Kyeremeh, like Ong, has argued that folk media, as traditional forms of communication, have evolved as grassroots expressions of the values and lifestyles of the people and, because they use local languages with which the people are familiar, have become embedded in their cultural, social, and psychologic thinking. Folk media are used to communicate entertainment, news, announcements, persuasion, and social exchanges of all types. They are a means by which a culture is preserved and adapted. Research has shown the importance of informal interpersonal contacts in persuading people to adopt or reject innovations; these contacts are often made through folk media.4 The power of folk media in changing behaviors in rural Africa results largely from the media's originality and the audience's belief and trust in the sources of the messages, which often come from people real to their audiences.

Folk media include storytelling, puppetry, proverbs, visual art, drama, role-play, concerts, gong beating, dirges, songs, drumming, and dancing.

Despite their power to capture people's imagination and subsequently to change behaviors, the use of folk media in health education campaigns has not been fully described in Western literature. These media (or the messages they convey) are often thought of as folktales, myths, and other fantasies that are individual misrepresentations of social events and occurrences and therefore have no or limited educational value. On the contrary, folk media are collective and imaginative constructions of the mind that figuratively explain aspects of rural folkways and at the same time delight their recipients. Because folk media address local interests and concerns in the language and idioms that the audience is familiar with and understands, they are appropriate communication channels for populations in rural areas.

USE OF FOLK MEDIA IN BEHAVIOR CHANGE STRATEGIES

Contemporary theories of cognition and communication can be used to explain the role of folk media as complex, nonformal methods of educating people and changing behaviors. The function of folk media is consistent with Bandura's social learning (cognition) theory, which states that most behaviors are learned through modeling. This theory explains that vicarious learning from others is a powerful teacher of attitudes and behavior. Bandura believed that individuals learn not only in classrooms but also by observing role models in everyday life, including characters in movies and television programs.5 Accordingly, folk media performers are role models from whom people learn. The various types of folk media are used as primers that provide the basis for residents of rural communities to discuss and diagnose their sociocultural and health situations and that enable them to take steps to find solutions to those problems. The role of folk media further subscribes to Rogers's communication and innovations theory, which explains how an innovation can be sustained within communities or groups of people after it has been adopted by the leadership of that community or group.6

In the mid-1970s, Miguel Sabido of Mexico began to show that soap operas with social messages could promote behavior change.7 These soap operas have their origin in a folk medium—drama. The Modeling and Reinforcement to Combat HIV (MARCH) Project described in this issue carry on, and refine, the Sabido method in several respects. Precursors to the MARCH approach to entertainment–education that have used the Sabido method to encourage responsible sexual behavior can be found in Mexico, the Philippines, and Nigeria, as well as in Ghana itself.8 These programs also stem from folk media forms—music and drama.

Theatre for Communication Implementation and Development (Theatre CID), a local theatrical group affiliated with a nongovernmental organization called Center for the Development of People in Kumasi-Ghana, uses simulated live shows to educate curious crowds about pertinent health issues, such as family planning, breast-feeding, and HIV/AIDS.9 Scenes are created publicly without onlookers' knowing they are being acted out, and they frequently provoke discussions on issues as well as audience responses to the negative behaviors portrayed. In rural Ghana, local “concert groups” perform dramas designed to focus attention on various social issues. These events frequently encourage community discussions, and appropriate actions are collectively determined to address those issues. African musical heritage is rich with songs that serve the dual purpose of entertaining and educating the audiences about a wide range of health and other social issues. Funeral dirges, which were traditionally recited and sung at funeral celebrations to revere the dead, are now being created with messages about various health issues, especially the dangers of HIV/AIDS. Such compositions are even played on national and regional radio and television networks. In addition, anecdotal evidence from reproductive health projects being implemented by CARE International in the Wassa West and Adansi West districts of Ghana suggests that using puppetry and storytelling to stress the need for social harmony has helped improve spousal communication in the communities.10, 11

INTEGRATING FOLK MEDIA AND RADIO

The power of folk media to change behavior makes it an appropriate complement to the HIV/AIDS behavior change communication project being implemented in Ghana. The CCHI project is designed to use folk media in the context of modern behavioral change strategies. The Sabido method12 is one strategy that has been effective in numerous countries in bringing about positive changes in reproductive health attitudes and behavior and in promoting the adoption of other health measures. The CCHI project in Ghana will combine folk media with the Sabido method of broadcasting long-running serialized radio dramas to portray characters who will evolve to adopt positive reproductive health behaviors, such as condom use, family planning practice, breast-feeding, and early treatment of STDs.

Development of the dramas requires a period of formative research to assess the characteristics and resources in the target community, cultural influences on the target behavior, and local practices and customs. Theoretical principles of attitude formation and behavior change will be strictly adhered to in the development of characters and the story line. The Ghana project is currently at the formative research stage. Specific folk media that can be used as part of this strategy include audio-based methods for the radio dramas and visual arts for selected community-based activities that will be undertaken to augment the radio broadcasts. In societies where the level of literacy is low, visual arts can be powerful HIV/AIDS education channels. They often have a specific purpose. Traditional visual forms may include designs on fabrics and clothes, carvings, and paintings. Puppetry is also a form of drama with considerable potential for health education, especially because it is possible for the puppets to “talk” about sensitive topics that would otherwise be unacceptable for an actor to discuss in a drama.

WHY RADIO?

Radio is a powerful and credible information and entertainment medium in most developing countries. Because it is affordable and accessible, radio is the most popular medium in Ghana, especially with the recent upsurge in the use of regional and local FM radio stations. Portable battery-operated radio sets are frequently brought to farms and other rural locations, even in the remotest parts of Ghana. This availability gives radio the capacity of being heard by a large, diverse audience. Folk media such as storytelling, drama, poetry recitals, proverbs, and music promoted on the radio will appeal to rural audiences and potentially influence them to adopt responsible, healthy behaviors.

The use of FM radio also offers opportunities for interactive participation by local residents. Community groups and institutions, including traditional leaders, religious groups, youth associations, and men's and women's groups, will be asked to promote listenership, discuss priorities, and monitor and assess the project. To complement the stories broadcast during the radio soap opera, community drama troupes will periodically enact some episodes of the serial in order to raise issues for discussion by all community members. Technical personnel from CCHI and partner organizations will be available to explain any issue that may require clarification. Community members will also be encouraged to develop some of the themes into songs and stories to be sung and recounted during listenership group meetings, festivals, and other community gatherings. Furthermore, communities will be given assistance in developing puppetry presentations based on the theme of the serial, as a complementary medium to develop and sustain listener interest as well as generate community discussions.

EVALUATION

The flexibility and participatory nature of folk media render any predetermined evaluation strategies almost inapplicable. Moreover, for community members to truly appreciate any change in behavior, they should be empowered to set their own indicators and determine in their own way how these indicators will be measured and documented. Nevertheless, to fulfill our objectives, it will be essential to incorporate evaluation measures into this project. In addition to developing community-based, self-evaluation measures in concert with the project communities, we will explore methods for assessing the efficacy of folk media in the CCHI project, including the use of periodic knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) surveys; satellite listening clubs, or focus groups, which would be formed to listen to an upcoming radio serial and offer advice; community documentation; and anecdotes.

CONCLUSION

Although folk media have not been recognized in most Western literature as the most prominent means of education in all aspects of African social life, the effectiveness of folk media in changing negative social and reproductive health behaviors in rural Africa is clear. Rural Africa, including the setting we have described in Ghana, is endowed with rich, popular means of communication, including songs, proverbs, storytelling, drumming and dancing, drama, poetry recital, and arts and crafts. These popular media are used for such purposes as recreation, entertainment, ritual, ceremonies, communication (information), and religion. Furthermore, we believe that folk media can be accommodated by contemporary theories of communication, education, and behavior change. In fact, it may be that folk media are better suited for theory-driven communication interventions than such modern techniques as participatory rural appraisal and use of mass media, to which many Africans do not relate well. These new methods, though undoubtedly useful in several contexts, require rural villagers to “participate” in ways that are often incomprehensible to them. Conversely, because folk media are an immediately recognizable vehicle for education, they are easily accepted by most Africans. The importance of the “fit” of the communication approach to the behavior change objectives cannot be overemphasized.

It is therefore imperative for projects whose goals aim at behavior change and sustainability in rural African settings to recognize and use the potential of folk media for the benefit of the rural folk as well as project implementers and funding agencies. Finally, there is a need for research into the myriad folk media forms that abound in rural Africa, both to explore ways to preserve these media and to document the effects they have on behavior change in rural communities.

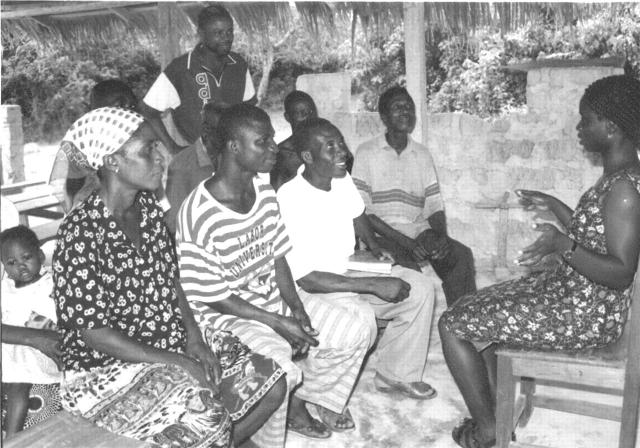

Figure 1.

A field supervisor leading a discussion after a drama performance in Ampunyase, a suburb of Obuasi, Adansi West District, Ghana, in December 2000. (Photo: Solomon Panford.)

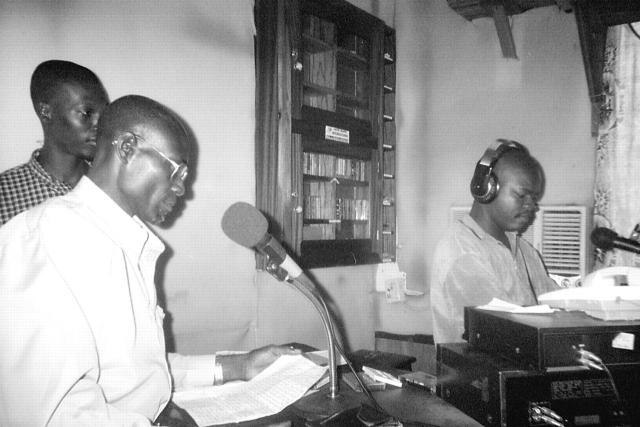

Figure 2.

A live broadcast at Dynamite FM studio, Tarkwa, Wassa West District, Ghana, February 2001. (Photo: Pat Riley.)

Acknowledgments

S. Panford originated the concept, drafted the initial abstract and outline of the paper, provided information on folk media, put the whole paper together with contributions from the coauthors, and reviewed the paper in accordance with editorial comments made by a number of editors. M. O. Nyaney provided information on folk media, contributed to the general outline of the paper, and read and reviewed the initial manuscript. S. O. Amoah reviewed the initial concept (abstract) and outline of the paper, provided information on adult learning, and provided most of the references. N. G. Aidoo provided information on prior use of folk media and read and reviewed the initial manuscript.

Support for this project was provided through an award of the R. W. Woodruff Foundation to CARE and the CDC Foundation for establishing the CARE– CDC Health Initiative.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Casely-Hayford L. HIV/AIDS in ECOWAS Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: UNESCO; 2000. Regional Discussion Paper No. 1.

- 2.Ong W. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the World. London, England: Methuen; 1982.

- 3.Ansu-Kyeremeh K, ed. Theory and Application. Accra, Ghana: School of Communication Studies, University of Ghana, Legon; 1998. Perspectives in Indigenous Communication in Africa; vol 1.

- 4.Hubley J. Communicating Health: An Action Guide to Health Education and Health Promotion. London, England: Macmillan Press Ltd; 1993.

- 5.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

- 6.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 1995.

- 7.Singhal A, Rogers EM. Miguel Sabido and the entertainment-education strategy. In: Entertainment-Education: A Communication Strategy for Social Change. London, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999:53.

- 8.Galavotti C. Modeling and reinforcement to combat HIV: the MARCH approach to behavior change. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1602–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Report on Activities of Theatre CID. Kumasi, Ghana: Centre for the Development of People (CEDEP); 1993.

- 10.Ashanti Region Community Health (ARCH) Project: Third Quarterly Report. Obuasi, Ghana: ARCH Project; 2000.

- 11.Annual Report, 2000. Tarkwa, Ghana: Wassa West Reproductive Health (WWRH) Project; 2000.

- 12.Swalehe R. Twende Na Wakati. Presentation at: Workshop on Radio Serial Drama, 2000; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 1999.