Abstract

This article examines the utility of a health and human rights framework for conceptualizing and responding to the causes and consequences of substance use among young people. It provides operational definitions of “youth” and “substances,” a review of current international and national efforts to address substance use among youths, and an introduction to human rights and the intersection between health and human rights. A methodology for modeling vulnerability in relation to harmful substance use is introduced and contemporary international and national responses are discussed.

When governments uphold their obligations to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights, vulnerability to harmful substance use and its consequences can be reduced.

We believe that the global war on drugs is now causing more harm than drug abuse itself. Every decade the United Nations [UN] adopts new international conventions, focused largely on criminalization and punishment, that restrict the ability of individual nations to devise effective solutions to local drug problems. … In many parts of the world, drug war politics impede public health efforts to stem the spread of HIV, hepatitis and other infectious diseases. Human rights are violated, environmental assaults perpetrated and prisons inundated with hundreds of thousands of drug law violators. Scarce resources better expended on health, education and economic development are squandered on ever more expensive interdiction efforts. Realistic proposals to reduce drug-related crime, disease and death are abandoned in favor of rhetorical proposals to create drug-free societies.

Public Letter to UN Sec-Gen Kofi Annan1

Explicit attention to the intersection of health and human rights can help reorient thinking about major global health challenges and, while contributing to broadening human rights thinking and practice, provide a solid approach for improving the lives of individuals.2 This intersection offers a framework for optimizing the contributions of both public health and human rights to conceptualizing the determinants of health and to thinking systematically about policy and program responses that promote both health and rights.

Substance use among youths is a worldwide epidemic. Young people start to use substances, singly or in combination, at early ages, and they report many different reasons for using them. Despite the harm that substances can and do cause, effective responses to substance use, and especially to harmful use among young people, remain limited. In this article we begin with brief discussions of concepts that often seem to warrant no definition: Who are “young people”? What “substances” are we talking about? What sort of substance use demands attention from public health and human rights perspectives and practitioners?

This discussion is followed by an introduction to human rights, particularly those of young people, and a discussion of the intersection of health and human rights in relation to substance use. These definitions and introductions are critical to ensuring a common conceptual starting point before we present a methodology for modeling vulnerability to poor health outcomes such as harmful substance use. The model illustrates how vulnerability to harmful substance use can be linked to the extent to which segments within the youthful population enjoy their human rights. The complement of this argument, discussed next, is that respecting, protecting, and fulfilling the rights of all young people can reduce their vulnerability to ill health, including the risk of harmful substance use.

We then review current international and national efforts to address substance use by youths and, using the vulnerability model proposed, suggest that these efforts are not only insufficient to ensure the human rights of young people as they relate to substance use but in some cases contribute to the violation of their rights. We conclude by suggesting ways in which human rights can help frame and shape more effective and comprehensive responses to substance use. While it is our contention that this approach is relevant to a variety of health concerns, substance use by young people is used as the example because it highlights the complexities that application of this model bring out and because the topic is of concern for anyone interested in the policy and program responses focused on youths more generally that exist worldwide.

THE DIVERSITY OF YOUTHS

Young people are not a homogenous group. As defined by UNICEF, young people include all people aged 10 through 24 years.3 They live in both industrialized and developing countries, in urban and rural areas or somewhere in between. Some attend school, others do not; some are literate, others are not. Some are employed under appropriate conditions; others work in situations of exploitation or are unemployed or underemployed. They may live with their parents or extended families or, because of death, migration, poverty, or family violence, live on their own or with other, unrelated, young people or adults. Young people may be parents themselves. Needless to say, they also vary by sex, race/ethnicity, class, and sexuality.

This is not an exhaustive list, nor does it specify how these different components of personal and social identity play out in different national and cultural contexts. However, it is crucial to recognize that it is often these factors, singly or in combination, that exacerbate or reduce young people's vulnerability to harmful substance use. The failure of policymakers to see young people in all their diversity and the exclusion of youths until some distant, arbitrary age of majority in political and social policy processes mean that the ways in which young people's rights are violated—including discrimination; abuse at home, at work, and on the street; separation from family; lack of educational opportunities or appropriate alternatives—can be underestimated or ignored. This paves the way for inadequate and inappropriate responses to preventing substance use and to reducing harm and treating use when it does occur.

DEFINING “SUBSTANCES” OF CONCERN

The annex to the 1971 United Nations (UN) Convention on Psychotropic Substances includes a list of chemicals denominated schedule I, II, III and IV drugs. Article 2 of the same convention gives more of a layperson's description of drugs that should be controlled: substances found to have “the capacity to produce a state of dependence [and] central nervous system stimulation or depression, resulting in hallucinations or disturbance of motor function or thinking or behaviour or perception or mood.”4 Substances most often discussed in the international literature include cannabis, cocaine, opium, heroin, amphetamine-type stimulants, Ecstasy, and inhalants.5–10 Despite a vast literature on tobacco and alcohol use by youth, these substances are generally not included in global discussions on substance use.11–13

It is important to recognize how “substances” are both lumped together and distinguished from each other in seemingly arbitrary ways that obscure the actual dangers of substance use, how these dangers differ from substance to substance and from user to user, and why. A review of the documents5–8,11 reveals interesting patterns. For example, cannabis, which is known to have low acute toxicity, require less treatment, and cause fewer deaths than many other substances, is often discussed together with more toxic, physically addictive, and potentially deadly substances such as cocaine, heroin, and Ecstasy. Alcohol, on the other hand, is often completely ignored, although it is the drug of choice among vast numbers of young people, has been reported to cause work-related problems and injuries more often than other substances,6 and in some countries causes more deaths and injuries among young people than any other substance.

IS ALL SUBSTANCE USE HARMFUL?

In many of the documents and much of the literature reviewed for this article, the overwhelming trend seems to have been to use the words “use” and “abuse” interchangeably, with little or no distinction made in the vast continuum of behaviors, states, and outcomes related to substance intake. The language used in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, is somewhat more explicit, but still insufficient: “harmful use” is defined as “a pattern of psychoactive substance use that is causing damage to health. The damage may be physical … or mental.” The term “harmful use” is used interchangeably with “psychoactive substance abuse.”14

The challenge of defining what, exactly, is unacceptable about substance use, in both public health and human rights terms, has not been adequately taken up by policymakers, researchers, or advocates of drug control. In one sense, virtually all use is harmful in some way. But at what point public health and human rights practitioners are called upon to prevent use, reduce harm, and treat young users will vary in response to a range of evolving social constructs, including what is considered to constitute appropriate behavior or free will, as well as economic imperatives, such as scarce resources and competing priorities.

In this article, we would like to highlight 2 questions regarding harm. The first asks why young people engage in substance use, noting that use, in fact, is a response to a range of very different issues. Although some youths, primarily in more developed countries but increasingly in less developed countries, use drugs, alcohol, and tobacco for social reasons or for “fun” (such users are often referred to in substance abuse literature as “socially integrated” youths11), other young people within the same environments may use these substances to work longer hours, enhance work or school performance or cope with academic pressure, alleviate hunger, reduce physical or emotional pain, fend off sleep, help to induce sleep, or lose weight.11,15–18 Others may use substances as a strategy to cope with war, unemployment, neglect, violence, homelessness, or sexual abuse.

The second question asks about the individual impact of substance use: How is the health and well-being of young users affected by their use? Harm could be defined in this case in a variety of ways, including dependence, overdose, HIV infection, sexual exploitation, inability to function within society, or involvement in criminal activity.

These questions are important because they draw attention to the inadequacy of discussing these issues for the sake of policy and program development without paying attention to assumptions and specific differences, and because they seek to clarify the range of issues that public health and human rights practitioners should address in their efforts to respond to substance use by young people.

DEFINING HUMAN RIGHTS

Human rights have a long history, but the modern human rights movement can be said to have been born with the UN, whose charter identifies the promotion of human rights as a principal purpose of the intergovernmental body.19 Human rights form part of international law, but the inspiration that underlies modern human rights—the notion that people are “born free and equal in dignity and rights”20 reflects an evolution in human thought about the relationship among human beings, particularly in relation to the state.

Beyond these hopeful aspirations, human rights offers a framework for conceptualizing and responding to the causes and consequences of public health issues. With centuries of philosophical and political thought to support it, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the UN in 1948 as a universal, common standard of achievement for all peoples and nations. Since then, a range of human rights instruments that further elaborate the rights set out in the Universal Declaration have been adopted and ratified by the governments of the world.21–28 As treaties, these documents form part of international law, which confers binding legal obligations on those states that ratify them.

Human rights include civil and political rights, such as the right to be free from torture and arbitrary execution, the right to information, and the right to free expression. They also include economic, social, and cultural rights, such as the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to health, and the right to education. The right to be free from discrimination is understood to be overarching and relevant to all rights. The content of these rights—how they can be translated from legal language into action—continues to be developed in countries throughout the world.

This process of turning legal language into policy and program responses useful for health at the country level began to be widely shared in the form of the final documents that emerged from a series of international conferences held during the past decade (World Conference on Human Rights, Vienna, 1993; International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 1994; World Summit for Social Development, Copenhagen, 1995; Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing, 1995; UN Conference on Human Settlements, Istanbul, 1996).

RESPECT, PROTECT, FULFILL

Under human rights law, governments are obliged to respect, protect, and fulfill the rights contained therein.29,30 All rights imply all 3 levels of obligations. The obligation to respect human rights means that governments are required to refrain from directly violating rights. Respecting young people's right to education, for example, means that the state cannot arbitrarily bar young people from attending school because they have violated the law and have been incarcerated or are receiving treatment for substance use.

The obligation to protect human rights means that governments are required to prevent rights violations by nonstate actors, and, when they fail to prevent such violations, to ensure that there is a legal means of redress that people know about and can access. Protecting young people's right to life means, for example, that the government is required to prevent the vigilante murder of street children assumed to be substance users. Should such killings occur, the state is required to conduct a full investigation, prosecute the accused, conduct a fair trial, and punish those found guilty.

The obligation to fulfill human rights means that governments are required to take positive steps, including administrative, legislative, budgetary, judicial, and other measures, to ensure the full realization of rights. Offering and ensuring access to appropriate information, outreach, and service delivery programs aimed at preventing, reducing the harm of, or treating substance use by young people is one way states can fulfill young people's rights to health and to information.

All areas of government, including health ministries, are responsible for respecting, protecting, and fulfilling human rights in the work they do. Consequently, rights must be explicitly incorporated into the work of public health. States' compliance with their human rights obligations is formally evaluated by international monitoring bodies in periodic sessions. Increasingly, monitoring and advocacy activities are conducted by nongovernmental organizations, the media, and private individuals.

HUMAN RIGHTS AND YOUNG PEOPLE

Each of the major human rights treaties—including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women; and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination—contains rights obligations that are applicable to young people.

Moreover, in 1990, the first human rights document to focus specifically on the rights of children—the Convention on the Rights of the Child—came into being.24 The convention distinguishes itself from earlier documents in its scope and in its reconceptualization of children and their position in society, particularly in its explicit articulation of the standing of children in terms of their rights, rather than as objects of charity or goodwill.31

The Convention on the Rights of the Child is a particularly powerful document. Adopted by the UN General Assembly and opened for signature by governments in late 1989, the convention entered into force less than a year later, more quickly than any other human rights treaty. Currently, the convention has has been ratified by every government in the world except those of the United States and Somalia.24 As such, and by defining “the child” as every human being younger than 18 years, the convention offers further protection to a large proportion of those whom UNICEF identifies as “young people.”

HEALTH, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND SUBSTANCE USE

“Whether illicit drug use should be considered a crime, a disease, a social disorder or some mixture of these is debated in many countries. Often, public policy is ambivalent about the nature of addiction, with social attitudes towards drug abuse reflecting uncertainty about what causes abuse and who is ultimately responsible.”6 The health and human rights framework springs from the mutual and dynamic relationship that exists between health and human rights. Acknowledging this relationship offers a powerful tool for predicting and explaining the distribution of health outcomes, for evaluating existing health policies and programs, and for conceptualizing and implementing new ones, to ensure that they promote public health in ways that are effective and consistent with human rights principles.

Put succinctly, the violation or neglect of human rights can increase the risk of poor health outcomes. Applied to the issues of concern here, a health and human rights framework would illustrate that the violation or neglect of young people's rights, a human rights concern in and of itself, can increase the risk of substance use, especially harmful use. Such violations would include, for example, the failure to respect, protect, and fulfill young people's rights to information, education, recreation, and an adequate standard of living.

It is important to note that, conversely, substance use by young people may further negatively affect the extent to which their rights are respected, protected, and fulfilled. Premature—and avoidable—morbidity and mortality, along with the marginalization that stems from harmful use, are manifestations of the violation or neglect of a range of rights contained in the human rights treaties, including the right to nondiscrimination and the right to health.

It is also important to note that although violation or willful neglect of rights is never permissible, there may be instances where it is legitimate for a government to restrict the rights of an individual, whether child or adult. For example, imprisonment of an individual who has been tried and found guilty of a crime is ordinarily considered a legitimate restriction on the right to freedom of movement. Such restrictions must comply with strict criteria to be considered legitimate under human rights law.32

The relationship between health and human rights is thus dynamic and mutually reinforcing. By taking steps to respect, protect, and fulfill the rights of young people, governments can reduce both the risk of substance use and the harm that it causes.

MODELING VULNERABILITY

The concepts of risk and risk-taking behavior gained prominence in the 1980s, as it became evident that much of the morbidity and mortality among young people was connected to behavior. The literature often looked to individual behavior as the cause of the problem at the exclusion of the larger and more powerful forces that served to influence individual behavior. Although research into risk-taking behaviors began to explore the antecedents and consequences of such behaviors, it appears that these behaviors were by and large assumed to be undertaken volitionally and, in the case of adolescents, to follow a developmental trajectory.33 In addition, it was assumed that a conscious weighing of alternative courses of action was present.34 Whereas the literature acknowledged the influential role of peers, parents, family structure and function, and institutions in risk-taking behaviors, and recognized that risk-taking behaviors were found to “share similar psychological, environmental, and/or biological antecedents,”34 the possibility that these antecedents may in fact be consistent predictors of harmful use was not sufficiently discussed.

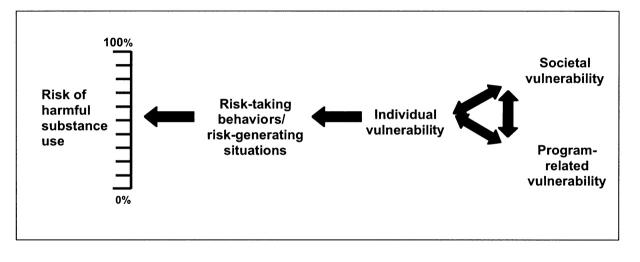

A methodology for modeling vulnerability, developed in the context of understanding the relationship between human rights and HIV/AIDS,35–37 is adapted here to explore the relationship between human rights and substance use by young people. This model starts where traditional models of risk leave off, developing the concept of vulnerability to more fully explain the factors leading to risk and risk-taking behaviors and thereby highlighting a range of necessary policy and programmatic responses. A health and human rights framework can then be used to guide the design of responses to eliminate or ameliorate sources of vulnerability and, ultimately, risk.

Drawing on the definition used in the HIV/AIDS literature, vulnerability is understood as a limitation on the extent to which people are capable of making and effectuating free and informed decisions.37 Greater vulnerability is likely to lead to greater involvement in riskgenerating situations and risk-taking behaviors, both of which increase the risk of poor health outcomes. The concept of vulnerability expands the traditional risk factor approach by illuminating the context in which individual experience is embedded, thereby opening the door to thinking more broadly about the causes of poor health outcomes and about appropriate public health responses. The components of vulnerability (discussed below) are, in turn, shaped by the extent to which human rights are realized.

Using the concept of vulnerability expands the range of risk factors considered relevant to a given health outcome (Figure 1 ▶). In addition to traditional risk factors, the concept goes further to include other individual, programmatic, and societal factors—such as substance use in the family or community; family violence and other forms of psychological, physical, or sexual abuse and exploitation; inadequately targeted care and support programs; education and poverty levels; employment possibilities; and homelessness—to explain harmful substance use.

FIGURE 1—

Model of individual, societal, and program-related vulnerability leading to risk behaviors and to individual risk for substance use.

Source. Adapted from Gruskin S, Tarantola D. HIV/AIDS, health and human rights. In: Lamptey P, Gayle H, Mane P, eds. HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Programs in Resource-Constrained Settings: A Handbook for the Design and Management of Programs. Arlington, Va: Family Health International. In press.

Individual vulnerability is characterized by personal history, knowledge, and behavior. Behavioral factors stem from personal characteristics—such as emotional and cognitive development, perception of and attitudes toward risk, family history of deprivation or abuse—and skills, including, for example, the ability to stand up to others or to oneself in refusing or limiting one's consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and other substances.

Program-related vulnerability considers the impact of health policies and programs on risk-taking behavior, risk-generating situations, and, therefore, on risk for harmful use. For example, drug use prevention programs that ignore the existence of, or variations in, young people and therefore their particular vulnerabilities to use38 can be understood to be an element of program-related vulnerability. The fragile legal status and social acceptability of some prevention and treatment initiatives themselves, such as needle exchange programs, can also be seen to exacerbate vulnerability.

Societal vulnerability is determined by the social structures that have the power to influence—positively or negatively—risk-generating situations, risk-taking behavior, and, ultimately, risk. These structures include socioeconomic conditions, the social environment35 and infrastructure, political participation, and cultural norms. For example, members of a stigmatized population group, whether because of poverty, ethnic group, or geographic location, may find their risk of harmful use increased because of their societal vulnerability.

Individual, program-related, and societal vulnerability interact and reinforce each other in ways that can increase the probability that young people will find themselves in riskgenerating situations (e.g., homelessness or sexual exploitation) and engage in risk-taking behaviors (e.g., substance use), thereby increasing their risk of poor health outcomes. This model highlights, for example, the fact that ongoing marginalization of the poor may result in scarce resource allocations to certain communities, leading to inadequate educational and employment opportunities, few prevention programs for young people, ignorance or lack of prioritization of the potential dangers of substance use, and reliance for economic or social support on other young people who sell or use drugs.

Precisely because each of the components of this model reinforces the others, rightspromoting interventions at any point can have a positive, multiplier effect. When interventions are consciously made at several points, the potential effect may be even greater. As a result, it is postulated that when governments respect, protect, and fulfill the range of human rights, young people's ability to mediate these different sources of vulnerability can be increased, reducing both risk and harm. When these efforts are complemented by efforts by health professionals and others, the impact may be considerable.

INTERNATIONAL RESPONSES

The international community has not consistently integrated human rights as a central and fundamental part of its understanding of substance use or in its efforts to reduce vulnerability, directly prevent use, reduce harm, or treat young users. Thus, international and national responses have remained fragmented and, in many cases, have violated the human rights of young people.

The international drug control system is governed by a series of international treaties that require governments to exercise control over production and distribution of narcotic and psychotropic substances and to take steps to combat drug abuse and illicit trafficking.4,9,10 The UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs is the main policy-making body for all matters of international “drug control.” All UN drug control activities are coordinated by the UN Drug Control Program, which was established in 1990. The UN Drug Control Program is financed through both the regular budget of the UN and a voluntary funded budget and is supported mainly through government contributions.

The system of administrative controls and penal sanctions outlined in the international drug treaties is seen largely to constitute prevention of substance use.39 The 1961 and 1971 conventions do, however, note that states parties “may provide, either as an alternative to conviction or punishment or in addition to punishment, that such abusers undergo measures of treatment, education, after-care, rehabilitation and social reintegration [emphasis added].”4,9 The language and thrust of the 1988 convention with respect to abuse is similar.10 With respect to prevention, the 1961 and 1971 conventions address measures to be taken against the abuse of psychotropic substances. The language in the 2 conventions is once again parallel and reads, “The Parties shall take all practicable measures for the prevention of abuse of psychotropic substances and for the early identification, treatment, education, after-care, rehabilitation and social reintegration of the persons involved and shall coordinate their efforts to these ends [emphasis added].”4,9,10 While it could be argued that language relating to prevention of harmful drug use is more sensitive to human rights than that dealing with punishment, what is important to note is that penal sanctions remain the primary mechanism for dealing with prevention and with people who use drugs, while all services—treatment, education, rehabilitation, after-care and social reintegration—are optional, despite the fact that human rights obligates governments to promote and protect the rights of individuals living within their borders, including the rights to health and education.40

Despite evidence that years of expensive supply reduction efforts have been of limited effectiveness, almost universally the focus remains on reducing the availability of illicit drugs through law enforcement measures, with relative neglect of demand and harm reduction approaches.41,42 Wodak writes:

Over the last half century, drug policy has increasingly depended on efforts to restrict illicit drug supplies. Yet global drug production has grown steadily, accompanied by a global increase in consumption (most marked recently in developing countries). These trends have occurred while illicit drug law enforcement has progressively intensified in almost all countries with enlarged customs bureaus and police drug squads, more severe penalties for drug offense, and substantially increased funding for all components focusing on reducing supply.42

The allocation of spending for supply and control activities vs demand reduction activities provides an indication of current global priorities. In 1996 and 1997, the UN Drug Control Program budgeted 49% of its funds for supply and control activities globally, while demand reduction activities received only 31% of the overall budget. Multisector activities, including policy planning, development of master plans, and institutional strengthening, were allocated the remaining 20% of funds.43

Such a focus implicates international drug agencies in the neglect of human rights. In many places, funding for drug efforts comes from international sources, which help establish the priorities for countries supported by these funds. It is our contention that the UN Drug Control Program and other drug agencies—by focusing on the punishment, instead of treatment, of substance users, and by focusing on finding those who make and traffic in drugs instead of supporting people, especially young people, who are vulnerable to harmful substance use—inadvertently support countries in neglecting their human rights obligations.

There is no doubt that the intention of the international community is to decrease substance use in the world. Yet the priorities put into place, budgetary allocations provided, and methods currently used to respond to that goal must be examined more closely for their integration of human rights principles.

NATIONAL RESPONSES

National responses to harmful substance use are as diverse as the countries that have created them. While some countries have long or relatively successful histories of addressing substance use and abuse, others have relatively new or ineffective responses, including prevention and treatment as well as punishment for cultivation, possession, and trafficking of illegal substances.

Tables 1 and 2 ▶ ▶ provide a global snapshot highlighting the differences in current national approaches. Table 1 ▶ provides a brief introduction to the existence and current implementation of laws and policies related to illegal substances; Table 2 ▶ presents a brief review of approaches to prevention and treatment. The countries chosen for inclusion are not meant to be representative of regions or continents, but, in providing illustrations of different approaches to substance law and policy, to raise questions concerning the apparent arbitrariness of the ways in which responses to substance use are designed and implemented.

TABLE 1—

Country-Specific Laws and Policies Relating to Substance Use and Abuse

| Bangladesh44 | Life imprisonment or death penalty for 25 g or more cocaine or heroin, 2 kg or more cannabis or opium |

| Cameroon18 | Law makes no distinction between cannabis, cocaine, and heroin, defining all as illicit drugs of high risk |

| Ethiopia18 | Law makes no distinction between categories of cultivator, dealer, and consumer, applying similar penalties to all 3 groups; police officers report delays in legal process, making it difficult to store forensic evidence, keep witnesses, and ensure that perishable exhibits can be used—all of which decrease the chance of rightful convictions |

| Ghana18 | It has been reported that those who cannot post bail spend up to 4 years in prison before trial |

| Malaysia51 | Broad power given to law enforcement agencies allows police and customs agents to intercept all mail, telephone, and telegraph communications and authorizes whipping of individuals convicted of possessing small amounts of illegal substances; mandatory death penalty for trafficking dangerous drugs (Malaysian courts sentence to death more than 200 drug offenders per year) |

| Netherlands45 | Decriminalization of use of and retail trade in cannabis products |

| Nigeria18 | National Drug Law Enforcement Agency has authority to conduct raids and investigations, monitor and freeze personal bank accounts, impound personal property, and monitor telephone lines |

| Syria46 | In the absence of mitigating circumstances, capital punishment for smuggling of narcotic drugs |

| United States43 | Five-year prison sentence given for both 500 g of powder cocaine and 5 g of crack cocaine; Black males constitute 12% of the population and 13% of drug users, but 55% of convictions for drug possession |

TABLE 2—

Examples of Available Drug Care and Treatment in Selected Countries

| Brazil47 | Successful reduction of risk through needle exchange programs |

| Czech Republic48 | Needle and syringe exchange programs in 5 urban areas; intensive drug prevention education implemented in secondary schools |

| Ethiopia18 | No medical establishments exist with facilities to treat drug addiction; anyone seeking medical care for addiction to an illegal substance is subject to arrest; many doctors report feeling pressure to report people who come to them for treatment |

| Japan49 | Few treatment centers that specialize in substance use for juveniles or adults; most treatment takes place in mental hospitals |

| Kenya18 | Money confiscated from convicts is to be diverted to the establishment of treatment and rehabilitation services (no monies thus far have been set aside) |

| Nepal48 | Needle and syringe exchange programs in 2 urban areas |

| Nigeria18 | Treatment includes investigation for physical, mental, and social “deficits”; detoxification, psychotherapy, and drug-free counseling; educational, social, and vocational rehabilitation (high treatment failure rates reported) |

| Thailand39 | Drug awareness information integrated into school curriculum at all levels |

| United States50,55 | Possession, distribution, and sale of syringes remains a criminal offense in much of the country; federal government continues to prohibit use of federal funds for syringe exchange programs (HR 982, the “Keep Drug Needles Off the Streets Act,” which is still being debated, would permanently prohibit use of US federal funds for “direct or indirect” support of syringe exchange programs) |

| Zimbabwe18 | Plans for national drug awareness education and programs for drug treatment and rehabilitation facilities (neither plan has been implemented to date) |

Some countries are increasingly harsh in their responses, while others are undergoing radical drug reforms. As illustrated in Table 1 ▶, in some countries the laws acknowledge differences among substances, among activities related to substance use (cultivation vs personal use vs trafficking), and among appropriate punishments for these different substances and activities; most do not. Laws and sentencing are often arbitrary. For example, in Ethiopia it was recently reported that a man found guilty of possessing 2 g of cannabis received 1 year in prison and a fine of 2000 birr (US $250), while another man, found guilty of heroin trafficking, was sentenced to 1 year in prison and a fine of 1000 birr (US $125).18 Many legal systems are sufficiently underdeveloped that people suspected of drug use or trafficking can spend long periods in detention before being charged, while those actually charged can wait years before getting a trial. Overzealous drug control bodies are not uncommon and police brutality in the context of drug use is well documented in many countries, as are bribery and other forms of corruption.5,18

LAWS AND POLICIES REGARDING PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Drug prevention and treatment activities are limited in many countries. The chief reason cited is a lack of resources, which often results in the creation of boards, committees, and policies without funds for implementation. The National Policy on Alcohol and Drug Abuse in Zimbabwe has plans for national education on drug awareness and ambitious programs for drug treatment and rehabilitation facilities, but as of this writing neither had been implemented. Kenyan legislation states that money confiscated from convicts is to be diverted to the establishment of treatment and rehabilitation services, but while courts have accumulated funds, no monies have thus far been set aside.18

Prevention efforts targeting youth appear to be focused primarily around schools. In Thailand, drug awareness literature has been integrated into school curriculums at all levels, while in the Czech Republic, an intensive education program has been implemented in secondary schools.51 Although these programs are extremely important, they do not serve those who do not attend school or who cannot read.

The general deterioration of the public health service in many countries has also resulted in limited drug care and treatment (Table 2 ▶). Many countries, however, have initiated needle and syringe exchange programs to curb the spread of infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS. In Brazil and elsewhere, no evidence has been found that such programs increase the frequency of drug injection or the number of injectors.52,53 Despite the importance and success of this public health intervention, some countries have banned the implementation of needle exchange programs. Other countries, the United States among them, have prohibited federal funding but allow local communities to make their own decisions about whether to implement needle exchange.54

THEORY INTO PRACTICE

The vulnerability model provides an approach for analyzing the determinants of a range of health outcomes. As immense a problem as substance use may seem at first glance, human rights offers an approach for considering the steps policymakers, health professionals, and others can take to significantly reduce vulnerability. It enables the translation of broad aspirations, codified in legal language and obligations, into practical and actionable strategies.

Explicit attention to human rights can suggest different ways of thinking about causes, and thus can suggest responses that can help reduce societal, program-related, and individual vulnerability to substance use, especially harmful use. Explicit attention to human rights serves the dual objective of respecting, protecting, and fulfilling the rights of young people and promoting and protecting their health. In addition, it points to the need to think about immediate action as well as longer-term objectives and strategies. Finally, while in the first instance human rights entails government obligations, human rights also offers standards that can orient (and, in fact, already reflect) public health work by private actors, such as nongovernmental organizations and others concerned with the health and well-being of young people.

Table 3 ▶ illustrates how those working in prevention, treatment, and reduction of young people's vulnerability to substance use may think about human rights obligations vis-à-vis young people. The horizontal axis of the matrix is broken down by the range of governmental obligations—respect, protect, and fulfill—that must be satisfied to ensure that any right is fully realized. The vertical axis is broken down by the different policy and program responses required for 3 interrelated and equally important aspects of an individual's experience with substance use.

TABLE 3—

Governmental Human Rights Obligations in Relation to Harmful Substance Use

| Respect | Protect | Fulfill | |

| Prevention | Government not to violate rights of people in the design and implementation of drug prevention policies and programs | Government to prevent nonstate actors from violating the rights of people in the design and implementation of drug policies and prevention programs | Government to take administrative, legislative, judicial, and other measures to promote and protect the rights of people in the context of drug policies and prevention programs, including providing legal means of redress that people know about and can access |

| Treatment | Government not to violate rights directly in the design, implementation, and evaluation of drug treatment programs, including ensuring that programs are sufficiently accessible, efficient, affordable, and of good quality | Government to prevent nonstate actors from violating rights either in the design, implementation, and evaluation of drug treatment programs or in ensuring that programs are sufficiently accessible, efficient, affordable, and of good quality | Government to take administrative, legislative, judicial, and other measures, including sufficient resource allocation, to ensure that drug treatment programs are sufficiently accessible, efficient, affordable, and of good quality, as well as providing legal means of redress that people know about and can access |

| Reduction of vulnerability | Government not to violate the civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights of people directly, recognizing that neglect or violation of rights has direct impact on vulnerability | Government to prevent rights violations by nonstate actors, recognizing that neglect or violation of rights has direct impact on vulnerability | Government to take all possible administrative, legislative, judicial, and other measures, including the promotion of human development mechanisms, toward the promotion and protection of human rights, as well as providing legal means of redress that people know about and can access |

Source. Adapted from Tarantola and Gruskin.31

The matrix illustrates that governmental obligations to prevent harmful substance use among young people are both interrelated with and distinct from obligations to treat young people who already use or abuse substances, as well as obligations to reduce vulnerability to harmful substance use. The issues raised here are meant not to be highly detailed, but merely to serve as examples of the issues this approach brings to light.

Examples provided earlier demonstrate the usefulness of such a matrix. Despite scientific evidence that needle exchange programs reduce the spread of HIV and do not lead to increased drug use, the United States has banned the use of federal funding for such programs.55 This ban could increase vulnerability to negative health outcomes and could be understood to represent a breach of the governmental obligation to respect the human right to health. The pressure that doctors in Ethiopia feel to report anyone seeking treatment to the police has an impact on the government's ability to protect human rights and ultimately may have an impact on the health of addicts, many of whom may choose not to seek treatment for fear of incarceration. Nepal, on the other hand, has taken steps to fulfill its obligations by progressively increasing the number of needle exchange programs that exist within the country.

This matrix offers a critical approach for assessing the design and implementation of new and existing policies and programs and for addressing their practical implications from both public health and human rights perspectives. Ultimately, such an analysis could be extended to examine how approaches recognized as best health practice within each of these domains could contribute to advancing human rights in relation to each level of governmental obligation. Through this approach, it is hoped that responses to decreasing harmful substance use at the national and international levels could be enhanced.

MOVING FORWARD

As a first step, a human rights approach can be used by all concerned to assess government responsibility and accountability in terms of health. The proposed framework can be used, first, to explore how government action (or inaction) contributes to substance use or encourages harmful use by young people and, second, to explore how a government responds once substance use and the state's role in encouraging it have been brought to its attention. This may be done by examining the human rights treaties the government has ratified and using the matrix described above to assess the degree to which the government is respecting, protecting, and fulfilling relevant rights. This can lead to analysis of how the extent of the government's compliance projects itself into patterns of substance use by young people and what is done about the problem once it is identified.

Second, those in both governmental and nongovernmental sectors who are working in research related to substance use among young people can ask what new questions about substance use and abuse by young people are raised by the vulnerability model and the proposed framework.

Third, health policymakers, service providers, and others concerned with substance use among young people can use this framework to evaluate existing public health policies and programs, especially those not specifically dedicated to health but which may have a direct bearing on the frequency and distribution of substance use by young people (e.g., education, income generation, housing and infrastructure, rural development), in light of the obligations set forth above. Such an evaluation can serve as a tool for advocating, developing, and implementing new prevention policies in various sectors as well as for revising existing ones.

Finally, by identifying gaps in governments' compliance with their human rights obligations, nonstate actors—all those working in the nongovernmental sector as advocates, researchers, and service providers—can apply the human rights framework to their work and see how their work may complement state action in promoting and protecting both the health and rights of young people.

It is clear that for efforts focusing on reducing harmful substance use among youth to be successful and for human rights to be promoted and protected, functioning legal systems must be in place. The lack of a legal framework in many countries undermines domestic and international efforts to control drugs and to provide prevention and treatment services to the people. If good laws are in place but are not enforced or are enforced selectively, individuals may not feel protected by them, especially when the laws address what many see as private behavior. Governments, with the help of international agencies, must not only define what is legal and illegal but must put into place clear mechanisms to safeguard the rights of individuals in relation to the exercise of these laws. This assistance may include building and strengthening institutional capabilities to ensure due process and effective remedies.

CONCLUSION

The analysis of substance use by young people from a human rights perspective is in its infancy. Addressing substance use requires short-term approaches, including more effective measures to control drug supply, and long-term approaches, such as prevention education and treatment for addicts. Although short-term and long-term approaches are often seen as independent, placed in opposition to each other and forced to compete for resources, attention, and credibility, elements of both approaches are necessary parts of a comprehensive approach to the prevention of harmful substance use for present and future generations and therefore should be seen as interdependent.6 Both long-term and short-term approaches to supply and demand reduction must explicitly respect, protect, and fulfill human rights. Otherwise, they risk violating the rights of young people, both those who use substances and those who are vulnerable to use.

We have sought to demonstrate that if the rights of young people are respected, protected, and fulfilled, their vulnerability to and risk for substance use, especially harmful use, can be reduced. We not only offer the theoretical basis for using human rights in analysis but, by offering practical tools for its application, aim to show ways in which a combined health and human rights approach can be useful to concerned policymakers, health professionals, and others. We hope that the discussion presented here can serve as a next step in broadening the dialogue on new ways to promote and protect the health of young people that are effective, as well as—or precisely because they are—consistent with human rights principles.

S. Gruskin conceived, developed, and refined the idea for the paper and had primary responsibility for writing the paper. K. Plafker contributed to the interpretation and writing of the paper. A. Smith-Estelle provided original research and contributed to the interpretation and writing of the paper.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Public Letter to [United Nations SecretaryGeneral] Kofi Annan. June 1, 1998. Available at: http://www.lindesmith.org/news/un.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 2.Mann J, Gostin L, Gruskin S, Brennan T, Lazzarini Z, Fineberg H. Health and human rights. Health Hum Rights. 1994;1:6–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Youth Health—For a Change: A UNICEF Notebook on Programming for Young People's Health and Development. New York, NY: UNICEF; 1997.

- 4.Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971. Available at: http://www.incb.org/e/conv/1971/articles.htm. Accessed October 8, 2001.

- 5.World Drug Report Highlights. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Drug Control Program; 1997.

- 6.The Social Impact of Drug Abuse. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Drug Control Program, 1995. Also available (in PDF format) at: http://www.undcp.org/technical_series_1995-03-01_1.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 7.Youth and Drugs: A Global Overview. Report of the Secretariat. New York, NY: United Nations Economic and Social Council; 1999.

- 8.United Nations Drug Control Program, Drugs and Development. UNDCP Technical Series1994/06/01. Available (in PDF format) at: http://www.odccp.org:80/technical_series_1994-06-01_1.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 9.Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, as amended by the 1972 Protocol Amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961. Available at: http://www.incb.org/e/conv/1961/. Accessed October 8, 2001. [PubMed]

- 10.United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, 1988. Available at: http://www.incb.org/e/conv/1988/. Accessed October 8, 2001.

- 11.Youth and Drugs: A Global Overview. Report of the Secretariat. New York, NY: United Nations Economic and Social Council; 1999.

- 12.Economic and Social Council begins three-day high-level discussion on international cooperation to combat illicit drugs [press release]. New York, NY: United Nations; 1996. ECOSOC/5644.

- 13.McCarthy M. UN adopts plans to combat worldwide illicit drug use. Lancet. 1998;351:1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992.

- 15.Ozaki S. Current status of drug abuse among youth in Japan. Paper prepared for: WHO Conference on Youth and Substance Abuse in the Context of Urbanization; February 7–11, 2000; Kobe, Japan.

- 16.Boonmongkon P, Sanders S, Suttikasem P, Promchitta P, Sopikul K. Urbanization, youth and substance abuse in Thailand: lessons learned and new directions. Paper prepared for: WHO Conference on Youth and Substance Abuse in the Context of Urbanization; February 7–11, 2000; Kobe, Japan.

- 17.United Nations Drug Control Program. Bulletin on narcotics. 1994, Issue 1. Available at: http://www.undcp.org/bulletin_on_narcotics.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 18.The Drug Nexus in Africa. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention; March 1999. UNODCCP Studies on Drugs and Crime Monographs.

- 19.Charter of the United Nations. Available at: http://www.un.org/aboutun/charter/index.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 20.Universal Declaration of Human Rights. December 10, 1948. Available at: http://www.un.org/overview/rights.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 21.Redress—International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. UN GA Res 2200 (XXI). Available at: http://www.redress.org/uniccpr.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 22.International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. UN GA Res 2200 (XXI). Available at: http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/a_cescr.htm. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 23.Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. UN GA Res 39/45. Available at: http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/h_cat39.htm. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 24.Convention on the Rights of the Child. UN GA Res 44/25. Available at: http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/k2crc.htm. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 25.Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. UN GA Res 2106A(XX). Available at: http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/d_icerd.htm. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 26.African [Banjul] Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights. June 27, 1981. OAU Doc CAB/LEG/67/3 rev 5, 21 ILM 58 (1982). Available at: http://www.oau-oua.org/oau_info/charter.htm. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 27.Council of Europe (1950). European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms and its Nine Protocols. ETS No. 005. Available at: http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/EN/cadreprincipal.htm. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 28.American Convention on Human Rights. OAS Treaty Series No. 36. Available at: http://www.oas.org/. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 29.Eide A. Economic, Social and Cultural Rights as Human Rights. In: Eide A, Krause C, Rosas A, eds. Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: A Textbook. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: M. Nijhoff ; 1995:21–40.

- 30.Sullivan DJ. The nature and scope of human rights obligations concerning women's right to health. Health Hum Rights. 1995;1:368–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarantola D, Gruskin S. Children confronting HIV/AIDS: charting the confluence of rights and health. Health Hum Rights. 1998;3:62–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogation Provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. New York, NY: United Nations Economic and Social Council; 1984. UN Doc. E/CN.4/1984/4.

- 33.Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12:597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Igra V, Irwin C. Theories of adolescent risk-taking behavior. In: DiClimente RJ, Hansen WB, Ponton LE, eds. Handbook of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior. New York: Plenum Press; 1996.

- 35.Tarantola D. Risk and vulnerability reduction in the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Curr Issues Public Health. 1995;1:176–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Expanding the Global Response to HIV/AIDS Through Focused Action. Reducing Risk and Vulnerability: Definitions, Rationale and Pathways. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 1998.

- 37.Gruskin S, Tarantola D. HIV/AIDS, health and human rights. In: Lamptey P, Gayle H, Mane P, eds. HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Programs in Resource-Constrained Settings: A Handbook for the Design and Management of Programs. Arlington, Va: Family Health International. In press.

- 38.Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child: Luxembourg. Geneva, Switzerland: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights; June 24, 1998: paragraph 28. CRC/C/15/Add.92.

- 39.Commentary on the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Cited by: Tomasevski K. Health. In: Schachter O, Joyner C, eds. United Nations Legal Order. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1995:859–906.

- 40.Tomasevski K. Health. In: Schachter O, Joyner C, eds. United Nations Legal Order. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1995:859–906.

- 41.Drucker E. Drug prohibition and public health: 25 years of evidence. Public Health Rep. 1999;114:99–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wodak A. Health, HIV infection, human rights, and injecting drug use. Health Hum Rights. 1998;2(4):25–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Drug Report: Fact Sheet. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Drug Control Program; 1997.

- 44.United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention. Bulletin on narcotics. 1992, Issue 1. Available at: http://www.undcp.org/bulletin_on_narcotics.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 45.Grieg A. The War on Drugs and a Harm Reduction Response. Participant manual, Harm Reduction Training Institute Overview Course. New York, NY: Harm Reduction Training Institute; 1998.

- 46.Drucker E, Hantman JA. Harm reduction drug policies and practice: international developments and domestic initiatives. Overview of a symposium. March 22, 1995. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1995;72(2):335–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Resnicow K, Drucker E. Reducing the harm of a failed drug control policy. Am Psychol. 1999;54: 842–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The Lindesmith Center–Drug Policy Foundation. Focal point: needle exchange/syringe availability. 2001. Available at: http://www.lindesmith.org/library/focal9.html. Accessed October 8, 2001.

- 49.Bangladesh Narcotics Control Act, 1990. Available at: http://www.undcp.org/legislation.html. Accessed October 8, 2001.

- 50.Van Vliet H. Separation of drug markets and the normalization of drug problems in the Netherlands: an example for other nations? J Drug Issues. 1990;20:463–471. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Syrian Arab Republic Narcotic Drugs Law. April 12, 1993. Available at: http://www.undcp.org/legislation.html. Accessed October 8, 2001.

- 52.United Nations Drug Control Program. Bulletin on narcotics. 1993, Issue 1. Available at: http://www.undcp.org/bulletin_on_narcotics.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 53.United Nations Drug Control Program. Bulletin on narcotics. 1996, Issue 1. Available at: http://www.undcp.org/bulletin_on_narcotics.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 54.United Nations Drug Control Program. Bulletin on narcotics. 1989, Issue 1. Available at: http://www.undcp.org/bulletin_on_narcotics.html. Accessed October 5, 2001.

- 55.Needle exchange programs: part of a comprehensive HIV prevention strategy. US Dept of Health and Human Services fact sheet. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/1998pres/980420b.html. Accessed October 8, 2001.