Abstract

Objectives. These studies investigated (1) the effect of community bans of self-service tobacco displays on store environment and (2) the effect of consumer tobacco accessibility on merchants.

Methods. We counted cigarette displays (self-service, clerk-assisted, clear acrylic case) in 586 California stores. Merchant interviews (N = 198) identified consumer tobacco accessibility, tobacco company incentives, and shoplifting.

Results. Stores in communities with self-service tobacco display bans had fewer self-service displays and more acrylic displays but an equal total number of displays. The merchants who limited consumer tobacco accessibility received fewer incentives and reported lower shoplifting losses. In contrast, consumer access to tobacco was unrelated to the amount of monetary incentives.

Conclusions. Community bans decreased self-service tobacco displays; however, exposure to tobacco advertising in acrylic displays remained high. Reducing consumer tobacco accessibility may reduce shoplifting.

In-store self-service tobacco displays are aimed at increasing product availability, visibility, and brand awareness and stimulating trial and purchase of products.1 Self-service displays ensure direct consumer access to products while featuring tobacco advertisements. In addition to branding on products, cigarette displays show an average of 4 branded advertising signs2 and usually are located by the checkout counter, exposing all shoppers to tobacco advertising.

Many communities have adopted selfservice display bans to limit youth access to tobacco via illegal sales and shoplifting.3,4 Bans are viewed unfavorably by some merchants who fear loss of incentives from tobacco companies.5 Nearly two thirds of the merchants who own small stores reported receiving tobacco industry incentives.6 Tobacco companies pay incentives for the placement of displays to increase sales.3,7 Despite the potential loss of incentives, some merchants support elimination of self-service displays to reduce losses from shoplifting.3 Up to 50% of youth smokers have shoplifted cigarettes at least once.8 Stores with counter self-service displays may be nearly 40% more likely to experience shoplifting than are those without counter displays.8

Self-service display bans may reduce youth access; however, little is known about the effect of the bans on the in-store advertising environment. A study of 3 communities found that clear acrylic, Plexiglas-like displays replaced self-service displays in stores in communities with a self-service display ban.5 The acrylic displays are the same size as self-service displays, sit on the checkout counter, display “packs” of cigarettes, and feature multiple branded advertising signs. However, these displays do not serve the same function as self-service displays, because the cigarette packs are enclosed in a clear acrylic case, which renders them inaccessible. Acrylic displays comply with self-service bans by eliminating direct consumer access to cigarettes, yet they ensure in-store tobacco brand advertising.9

The 2 studies presented here, first, documented the relation between community self-service display bans and the in-store environment and, second, investigated the relation of the in-store environment to merchant incentives and shoplifting. In study 1, we counted and coded tobacco displays in a sample of stores in California communities with and without self-service tobacco display bans. The purpose of the study was to document how bans affect the use of tobacco displays. Tobacco industry documents have asserted that merchants who allow direct consumer access to tobacco (e.g., self-service displays) receive tobacco company incentives; thus, despite merchant concerns about shoplifting, it may be less profitable for merchants to limit consumer access to tobacco cigarettes.7 In study 2, we interviewed merchants to compare, in terms of tobacco incentives and shoplifting, stores that offer direct consumer access to tobacco products with stores in which merchants kept all tobacco products behind the counter.

STUDY 1: SELF-SERVICE VS ACRYLIC DISPLAYS

Methods

Tobacco advertising observations were completed in 586 stores drawn from a random sample of California stores that sold tobacco as part of a previous investigation of tobacco marketing in retail outlets.10 The sample included 69 large markets, 164 small stores (3 or fewer cash registers), 148 convenience stores with or without gasoline, 53 gasoline stations, 113 liquor stores, and 39 drug stores or pharmacies. Displays were defined as freestanding racks provided by cigarette manufacturers containing cigarettes and branded signs. Displays were coded as self-serve if the consumer could directly access the cigarettes without clerk assistance, clerk-assist if clerk assistance was required to access cigarettes, or acrylic if the display was enclosed in clear acrylic and neither consumer nor clerk could access the cigarettes. A list of communities with self-service tobacco display bans was secured from the Americans for Non-Smokers Rights (http://www.no-smoke.org).

Analyses examined how bans affected cigarette display use. All stores were classified by their community ban status (no ban vs ban). A χ2 analysis determined whether the proportion of stores featuring self-service displays was lower in communities with self-service display bans compared with communities without bans. We performed t tests to determine the relation between community self-service display policy and different kinds of displays.

Results

Fourteen percent (n = 82) of the stores were located in communities with self-service display bans, and 86% (n = 504) were located in communities without bans. Of those stores in communities with bans, 16% (n = 13) had at least 1 self-service display, in violation of local bans. In communities without bans, significantly more (40%, n = 200) stores featured self-service displays (χ21 = 8.4, P < .05).

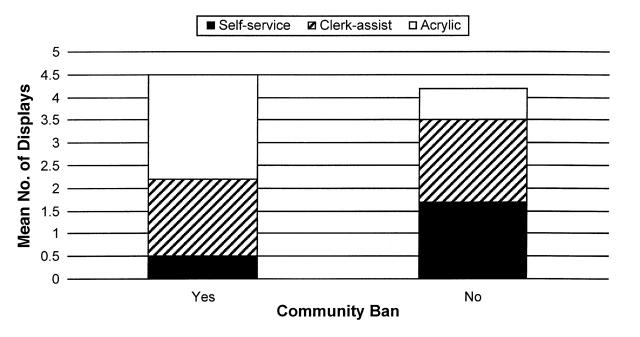

Figure 1 ▶ presents the mean number of displays per store by self-service ban status. Stores in communities with bans had significantly fewer self-service displays (mean = 0.5) than did stores in communities without bans (mean = 1.7, t584 = 3.6, P < .001). Stores in communities with bans had about the same number of clerk-assist displays (mean = 1.7) as stores in communities without bans (mean = 1.8, P = .723). In contrast, stores in communities with bans had significantly more acrylic displays (mean = 2.3) than did stores in communities without bans (mean = 0.7, t584 = 7.9, P < .001). Community self-service ban status was not related to the overall number of displays in a store; stores in both ban (mean = 4.5) and no-ban (mean = 4.2) communities had about the same number of total displays (P = .576).

FIGURE 1—

Type of tobacco display in stores, by community ban status: California, 2000.

STUDY 2: TOBACCO PLACEMENT AND MERCHANT INCENTIVES

Methods

Following completion of the in-store advertising surveys described in study 1, stores were contacted by telephone, and research staff interviewed the store employee who was responsible for negotiating contracts with sales representatives. If store negotiations were performed at the corporate level, then the store was ineligible for the merchant interview. Calls eliminated 466 stores that either did not meet eligibility criteria or whose responsible employee was not available for an interview, so the in-store advertising survey sample was augmented with 78 merchant interviews drawn from a list of 461 stores obtained from a leading provider of store lists for the marketing research industry. Interviews were completed at a total of 198 stores that represented large markets (n = 11), small stores (n = 65), convenience stores with or without gasoline (n = 62), gasoline stations (n = 20), and liquor stores (n = 40).

Trained staff members conducted merchant interviews in English. A university internal review board approved all procedures. Merchants reported whether they stocked cigarettes and tobacco on self-service displays or on shelves accessible to consumers or whether they kept all cigarettes and tobacco products behind the counter, inaccessible to consumers. Merchants reported whether they received any incentives from tobacco companies, including discounted products, free goods with an order, “buy downs” (the manufacturer refunds the merchant for products they have on hand to lower prices of current stock), or money. If merchants received money, they were asked how much money they had received in the past 3 months. Merchants also reported the amount of money lost in a typical month from shoplifting of tobacco.

We performed t tests and χ2 analyses to assess the relation of direct consumer access to tobacco products to merchant incentives and shoplifting.

Results

Most merchants (57%) reported receiving incentives and money (37%) from tobacco companies. Table 1 ▶ presents incentives, money received, and shoplifting by placement of tobacco. Merchants in stores with selfservice tobacco displays were more likely to receive incentives (χ21 = 8.0, P = .005) and money (χ21 = 5.9, P = .015) than were merchants in stores with all tobacco behind the counter. However, the amount of money received from tobacco companies did not differ for merchants with and without self-service tobacco (t71 = 1.2, P = .233). The amount of money lost to shoplifting was more than 3 times greater in stores with self-service tobacco (t70 = -4.9, P < .001).

TABLE 1—

Incentives, Money Received, and Shoplifting in Stores With Self-Service Tobacco vs All Tobacco Behind the Countera: California, 2000

| Self-Service Tobacco (n = 57) | Tobacco Behind the Counter (n = 141) | Total Sample (N = 198) | |

| Received tobacco incentives** | 73.2% | 51.1% | 56.6% |

| Received tobacco money* | 54.9% | 35.2% | 36.9% |

| Amount of money received in past 3 months, mean (SD) | $258 ($449) | $226 ($489) | $236 ($477) |

| Money lost to shoplifting in typical month,** mean (SD) | $100 ($100) | $29 ($57) | $50 ($78) |

aSelf-reported.

*P < .05; **P < .01.

DISCUSSION

The goals of the 2 studies were to document the relation of community self-service tobacco display bans to the in-store environment and to investigate the relation of the in-store environment to merchant incentives and shoplifting. Community bans limit self-service displays; however, our findings suggest that bans do not reduce the amount of tobacco brand advertising on acrylic displays. In study 2, more stores with consumer-accessible tobacco received incentives; however, actual amounts of money that stores received did not differ as a function of the location of tobacco products, and losses from shoplifting were substantially higher in stores with direct consumer access to tobacco.3,7,8

Tobacco industry documents state that visibility and brand awareness are important goals of tobacco advertising,1 and tobacco control policies are needed to effectively combat these goals. The amount of advertising on displays in stores remains unchanged in the face of bans, because acrylic displays replace the advertising typically found on self-service displays. Acrylic displays function solely as advertising, accomplishing key goals of the tobacco industry. This finding suggests that brand displays are designed to spur sales to stimulate and maintain use of cigarettes.

Policymakers who regulate the in-store environment will need to partner with merchants to ameliorate concerns that may arise from the higher reported frequency of incentives given to merchants with direct access to tobacco. Despite these reports, actual amounts of money received were not related to tobacco access. Consistent with other reports,3,8 another important benefit of community bans was that stores without direct consumer access to tobacco lost far less (more than 3 times less) money from shoplifting than did stores with consumer access. Merchants report that tobacco industry advertising produces a “cluttered” appearance in their stores.3 A desire for reduced shoplifting losses and a clean-looking store may outweigh incentives from tobacco companies. These positive points may be useful in persuading merchants to eliminate tobacco displays.

These data were drawn from California, and our surveys had a high refusal or unreachable rate. Our data may not be generalizable to tobacco promotion in other locations, and inferences must be made with caution. We were unable to examine the direct relation between community bans and merchant incentives, because we excluded many corporately owned stores in study 2. Research is needed to document this relation and to investigate how corporate negotiations may affect tobacco advertising and merchant incentives. Last, our merchant incentive interviews relied on self-reports that may have overestimated or underestimated incentives or shoplifting.

The use of acrylic displays appears to be a strategy by tobacco companies to satisfy self-service display bans while maintaining advertising exposure. We found that acrylic displays provide a mechanism for prominent tobacco advertising at the point of sale. Research is needed to document and define other effects of acrylic displays on shoppers. Our results call into question claims that self-service bans will reduce net profits by reducing tobacco industry paid incentives and suggest that greater regulation may be needed to reduce unwitting exposure to tobacco advertising.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by funds received from the Tobacco Tax Health Protection Act of 1988—Proposition 99 through the California Department of Health Services under contract 94-20967-A04 and supported in part by an institutional grant (HL 58914) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Kurt Ribisl, PhD, for his thoughtful comments and suggestions on the paper.

E. C. Feighery conceived of the study and supervised all aspects of its implementation. S. Halvorson assisted with the study and completed the analyses. R. E. Lee synthesized analyses and led the writing of the paper. N. C. Schleicher assisted with the study and analyses. All authors helped to conceptualize ideas, interpret findings, and review drafts of the paper.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. New Product Introduction Through Point-of-Purchase. Bates #500164188-500164208; 1978. Available at: http://www.tobaccodocuments.org. Accessed October11, 2001.

- 2.Feighery EC. A study of tobacco ads, retailer incentives and sales to minors in four central California communities. Report to the California Department of Health Services, Tobacco Control Section; 2000.

- 3.Wildey MB, Woodruff SI, Pampalone SZ, Conway TL. Self-service sale of tobacco: how it contributes to youth access. Tob Control. 1995;4:355–361. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2000.

- 5.Bidell MP, Furlong MJ, Dunn DM, Koegler JE. Case study of attempts to enact self service tobacco display ordinances: a tale of three communities. Tob Control. 2000;9:1–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Achabal DD, Tyebjee T. Retail trade incentives: how tobacco industry practices compare with those of other industries. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1564–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. Pilferage Presentation. Bates #51434-8983; 1976. Available at: http://www.tobaccodocuments.org. Accessed October11, 2001.

- 8.Caldwell MC, Wysell MC, Kawachi I. Self-service tobacco displays and consumer theft. Tob Control. 1996;5:160–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UICC GLOBALink The International Tobacco Control Network. Legislation on underage sales of tobacco [bulletin board posting]. Available at: http://www.globalink.org. Accessed March 15, 2000.

- 10.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Schleicher N, Lee RE, Halvorson S. The tobacco industry's use of retail advertising and promotions: a statewide survey of California stores. Tob Control. 2001;10:184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]