UNEQUAL DIVIDENDS OF PROGRESS

About 30 percent of persons aged 65 and over today, owe their survival to progress in medicine, public health and general welfare since the year of their birth. The benefits of this progress and the chance it affords for increased longevity have not, however, been uniformly available to all elements of the American population. We have tended to operate on the principle that one is entitled to only such medical care as he can pay for, with the result that the best medical personnel and facilities have become concentrated in our urban centers of greatest wealth. This leaves rural areas and people in the lower economic brackets, who need medical care most, receiving least. . . .

NEGRO HEALTH STATUS

Although the Negro has shared in the benefits of modern medical advances, he has never done so as fully or as rapidly as the rest of the population and he brings up the rear of backward regions. The average American life expectation has been increased from 35.5 years in 1789 to about 64 years today, but Negro life expectancy has shown a constant lag of about 10 years behind the white. In 1940 the life expectation of Negroes at birth was 52.26 years for males and 55.56 years for females; that of whites 62.81 years for males and 67.29 years for females.

The Negro mortality rate has declined from 24.1 in 1910 to 14.0 in 1940, but the latter figure was 71 percent higher than the rate of 8.2 for whites. Nearly all diseases which show excess mortality in the Negro are classed as preventable. Conditions like tuberculosis, maternal and infant mortality and venereal disease, regularly show high incidence in any group of low economic status, where there is ignorance, overcrowding, poor nutrition, bad sanitation and lack of medical care. . . .

PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL

It is not our premise that the number of Negro physicians in the United States should be determined by the number of Negroes, but if physician-population ratio is considered on a racial basis, there should be 9,334 colored physicians today, assuming the Negro population to be 14,000,000. This is more than twice the existing number. Consequently, a large portion of the Negro population receives such medical care as it obtains from white physicians who, in many cases, find this service an inconvenience. . . .

NEGRO MEDICAL GHETTO

The Negro medical man has had to work out his problems in a nationally dispersed professional “ghetto.” Many have become so conditioned to the arrangement that too often they think it the only one possible and believe, as is frequently asserted, that one is being “unrealistic” if he thinks otherwise. . . .

None, second, third, or fourth rate hospitals have largely been the portion of the Negro people. This lack of adequate hospital facilities has been the greatest material handicap to the receipt of adequate medical care by the patient and adequate postgraduate training by the profession.

There are 112 Negro hospitals in the United States, of which some 25 are accredited and 14 approved for the training of internes. The number of hospital beds available to Negroes is in the neighborhood of 10,000. It is the current accepted standard that there should be 4.5 general hospital beds per 1,000 of population. . . . In Mississippi in 1938, a survey by the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals of the American Medical Association, found 0.7 beds for Negroes and 2.4 for whites. Although in the four years preceding the survey there had been a steady increase in the number of hospital beds, facilities for Negroes had increased less rapidly than those for whites. The comment of the report is extremely enlightening on the attitude apparently of the State and the surveyors toward Negroes. It states, “In appraising medical services in this state one must take into account the fact that over 50 percent of the population in Mississippi are Negroes and that the demand for medical service among this group may fall below the requirements for the white population. . . .”

OLD CLOTHES TO SAM: THE HOSPITAL DILEMMA

In effecting the denial of adequate hospital facilities to Negro patients and physicians, our segregated social system has achieved some of its most vicious effects. All over the country the secondhand hospital stands as a symbol of what the system means. Let us see how it operates.

Meditation—“I’m getting a new suit, but this old one is too good and cost too much to throw away. I'll turn it over to Sam. He needs a suit. This one isn't new, but it' better than anything he has or can get now. With a few alterations, this will be just right for him. He ought to appreciate it, even be grateful enough to pay as much as he can afford for it. Maybe he'll pay more than it' worth, prices being what they are. After all, for him this will mean progress.

“Sam is getting a little sensitive though. Time was when he would thankfully accept whatever was offered. Now he talks about not wanting ‘cast-offs.’ I'll have to find a way to give this an ‘anointing with oil.’ After all, this suit was designed and made by one of the world' leading tailors. How could he get one like it—and it' practically as good as new. I'll just tell him frankly that his needs have been recognized and received a great deal of thought for a long time. In his economic position, he will understand that he can't have everything at once and something as good as this is ten times better than nothing. Don't we all have to be realists? Sam will be realistic and not be misled by any of his dreamier friends.”

Pattern—Rationalizations of this type accompany the transfer of many secondhand products of modern American culture to Negro hands as the brown population increases in an urban community. When the whites vacate a neighborhood or section, they generally move to a newer and better one, leaving behind not only their dwellings, usually sold at a profit or retained at higher rentals, but also their institutions—schools, churches and hospitals.

The transfer of residence ownership or rental involves no great problems, being a series of simple real estate transactions (covenants permitting). Schools and churches follow in natural order. The children of the newcomers either supplant those of their predecessors in the schools, or where there are separate systems, the building is “turned over” to colored when the numbers of the newcomers require it. Schools are public institutions, and as little private interest is concerned, this transfer occasions no excitement. Churches, particularly large ones, represent considerable private investments and are too expensive for the Negro newcomers to purchase outright, so the “turning over” of these is ordinarily delayed until brown encirclement is complete or so far advanced that the less pigmented Christians consider its relinquishment to their fellow worshippers of darker hue an absolute necessity. After the change, the fate of the Lord' temple, which may have cost enormous sums to build, is of no further concern to its original owners.

Hospitals—With hospitals, however, the situation is more complex. The white community faces two pressures. First, the necessity of disposing of the hospital they propose to vacate, either because a new one is being obtained or because change in the neighborhood from their point of view dictates a new one. Second, they are faced with providing a solution for the pressing health facility problems of Negroes, while at the same time maintaining the established segregation practices in white hospitals.

To turn over the relinquished hospital to Negroes kills both these birds and several others with the same stone. (1) It disposes of the real estate problem. (2) It provides Negroes with what appears to be better than they have. (3) It appeases the white conscience with the “do-good” activity involved. (4) From the white point of view, although the problem is not settled by this procedure, it is quieted for a while, and may be stalemated for the present generation, leaving the annoyance of further solution to descendants. (5) The cooperation of outstanding Negroes in promoting the deal may be drafted and all Negroes who oppose the arrangement may be vilified as being unrealistic, not having common sense, and foes of the progress of their own people. (6) Any deficiencies in the subsequent development of the hospital may be attributed to the inability of Negroes to conduct such institutions. . . .

Reflection—This review of one phase of hospital development in respect to the Negro cannot afford basis for comprehensive conclusions. Some things are obvious, however.

1. Under the present plan of privately owned duplicating hospital set-ups new institutions are beyond the financial reach of Negroes and they must, therefore, accept “cast-offs” under protest, embrace them opportunistically, or refuse them.

2. No matter how auspiciously launched it remains to be proved that the financial burdens and requisite professional standards can be maintained at these transferred institutions over any considerable period of time.

3. Under existing arrangements private financing cannot ever meet the needs of Negroes; hence, the question of public funds is raised. We are catapulted at once into the bizarre present-day situation where for purposes of hospitalization all citizens are either indigent or able to pay. If indigent a Negro can often go to a tax-supported hospital. If not, for much of the country, he is out of luck.

4. In the light of this single problem our whole philosophy of hospitalization may be questioned. The Hospital Construction Act as passed provides no remedy. The matter of Federal support for a broadly conceived and comprehensive plan for health care does offer possibilities of solution. . . .

NATIONAL LEGISLATIVE REMEDIES

Facilities and money have been the great obstacles to the poor and the remote in obtaining the medical care they needed. In the 79th Congress, two major pieces of legislation were introduced to overcome those obstacles. One, the Hill–Burton Bill, was designed to plan and construct hospital and health facilities of modern type all over the country, placed according to need, so that the best would be at hand to everyone. This measure received universal support and, considerably modified and reduced in scope, became law, as the Hospital Survey and Construction Act in August, 1946.

The other measure, the National Health Bill (Wagner–Murray–Dingell), was prepared to provide a means of financing complete health care for our whole population. It proposed to do this by increased appropriations for existing public health programs and by wage deductions for a health insurance fund. This bill did not pass. Major opposition was from the American Medical Association. Labor and welfare organizations generally, the Physicians Forum, which includes many eminent members of the profession, the NAACP, and the National Medical and Dental Association, representing Negro physicians and dentists, supported the bill. These groups did not regard this omnibus legislation as perfect, but they viewed it as the best solution so far evolved for bridging the economic gap between medical care and those who need it most.

Although the National Health Bill did not pass, it has been reintroduced, with revisions, in the present 80th Congress and President Truman has made an even more urgent plea for its adoption than for the previous measure. The opposition has sensed public demand enough to require it to produce a counter-measure, S. 545, commonly known as the Taft Health Bill, which is essentially the proposal of the American Medical Association. This bill has many major objectionable features, such as organizational arrangements which would permit AMA control of the plan, and non-discrimination clauses which would be nullified by the prescription for administration of the program by the states, and so on, but bad as it is, S. 545 makes unanimous the acknowledgment that “something must be done.”

FINALE

From this brief review it is completely obvious how badly the segregated social system has retarded improvement of health in the Negro. It is only too clear, from the patterns which his medical care advances, no matter how commendable, have had to take, that there is no real intention on the part of the majority to uproot the confines of the ghetto. Silent penetration with the quiet demonstration of merit and need has certain limited values, but the Negro has nothing to hide in aims or objectives. The situation demands that America be informed and that she take notice and remove the entrenched and discriminatory practices in education, professional training and hospital customs which so blatantly indict us before the world, and impair the prestige of our leadership in the health organization of the United Nations.

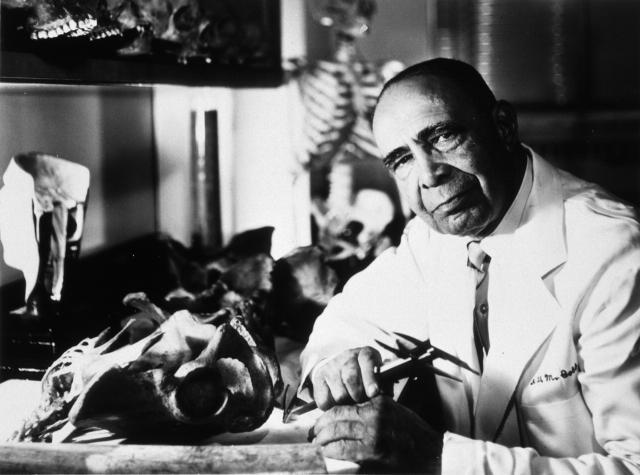

Figure .

Source. Prints and Photographs Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine.