Abstract

This commentary presents an “indigenist” model of Native women's health, a stress-coping paradigm that situates Native women's health within the larger context of their status as a colonized people. The model is grounded in empirical evidence that traumas such as the “soul wound” of historical and contemporary discrimination among Native women influence health and mental health outcomes. The preliminary model also incorporates cultural resilience, including as moderators identity, enculturation, spiritual coping, and traditional healing practices.

Current epidemiological data on Native women's general health and mental health are reconsidered within the framework of this model.

A people is not defeated until the hearts of its women are on the ground.

Traditional Cheyenne proverb

CORN WOMAN OF THE Cherokee, Spider Woman of the Hopi, Grandmother Turtle and Sky Woman of the Haudenosaunee—these and other spiritual female figures reflect the sacred and central positions that women have held among indigenous nations over many centuries. Contemporarily, Native women's power is manifested in their roles as sacred life givers, teachers, socializers of children, healers, doctors, seers, and warriors.1 With their status in these powerful roles, Native women have formed the core of indigenous resistance to colonization,2 and the health of their communities in many ways depends upon them.

Any discussion of the health of Native women must begin with a consideration of their “fourth world” context. According to O'Neil,3 fourth world refers to situations in which a minority indigenous population exists in a nation wherein institutionalized power and privilege are held by a colonizing, subordinating majority. An “indigenist” perspective is a progressive, Native viewpoint that acknowledges the colonized or fourth world position of Natives in the United States and advocates for their empowerment and sovereignty.4

Subordination of indigenous populations in the United States has taken many forms. The US government has sponsored policies of genocide and ethnocide, including distribution of small pox–laden blankets by the US army, forced removal and relocation of Natives from traditional land bases, and disproportionate placements of Native children into non-Native custodial care.4 Disempowerment of Native women specifically was a primary goal of the colonizers, with the intent of destabilizing and, ultimately, exerting colonial domination over each indigenous nation.2

For example, among the Cherokee, a traditionally matriarchal society, the British decreased the power of women by “educating” Cherokee males in European ways, encouraging marriage to non-Native women, and privileging mixed-blood male offspring in nation-to-nation negotiations.2 During the 1970s, the Indian Health Service (IHS) oversaw the nonconsensual sterilization of approximately 40% of Native women of childbearing age.2 More recently, Native women's anecdotal reports indicate that Medicare has denied funding for the removal of Norplant contraceptive devices, despite their high risk for deleterious side effects in women with diabetes. The cumulative effects of these injustices have been characterized as a “soul wound” among Native peoples5 and constitute considerable “historical trauma.”6

Our evolving work on Native women's health has led to a stress-coping model that incorporates an indigenist perspective. After presenting pertinent sociodemographic data, we describe this model along with data substantiating the need to consider historical trauma and current trauma as key stressors in the lives of Native women. Current epidemiological data on Native women are reconsidered from this perspective.

SOCIODEMOGRAPHICS

The 2.3 million American Indians and Alaska Natives residing in the United States constitute approximately 1% of the total population, and this group is expected to grow 44% (to 2.9 million) by the year 2030.7,8 According to census data from 1990, Natives, in comparison with the overall US population, were younger (39% vs 29% younger than 20 years), were more likely to reside in a female-headed household (27% vs 17%), had larger families (3.6 vs 3.2 members), had lower high school graduation rates (66% vs 75%), and were more likely to live below the poverty level (47% vs 13%).8,9 Native women, who represent 51% of the total Native population, are relatively young (median age: 23.3 years) and have a life expectancy rate of 74.7 years, 4.2 years less than the rate for US women overall.10 The mean income for employed Native women in 1989 was $14 800, $3000 less than that for employed Native men.11

AN INDIGENIST STRESS-COPING MODEL OF NATIVE WOMEN'S HEALTH

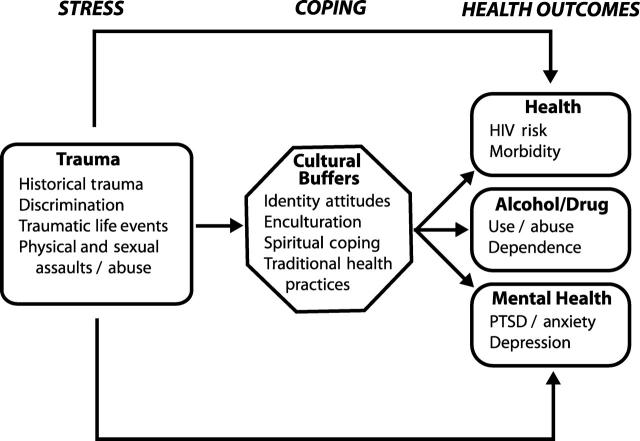

How do Native women cope with life stressors in the face of colonization, and what effects do life stressors have on their health? These questions have been at the heart of our development of an indigenist stresscoping paradigm. As can be seen in Figure 1 ▶, our modified stress-coping model posits that the effect of life stressors (e.g., historical trauma) on health is moderated by cultural factors such as identity attitudes that function as buffers, strengthening psychological and emotional health and mitigating the effects of stressors.

FIGURE 1.

—Indigenist model of trauma, coping, and health outcomes for American Indian women.

Our model is theoretically situated within the work of Dinges and Joos12 and Krieger.13 Dinges and Joos elaborated on an earlier model of stress and coping by including stressful and traumatic life events. In their model, environmental contexts and person factors are identified as potential mediators or moderators of stressful life events, and wellness outcomes depend on the interactions of internal processes with stress states. They found this model to be applicable to Native populations.

Krieger's work incorporates the health consequences of discrimination and ecosocial theory, highlighting the importance of incorporating identity processes and expressions of self as moderators of the discrimination–health outcomes relationship.13 With respect to the ecosocial framework, our model delineates the pathways between social experiences and health outcomes, thus providing a coherent means of integrating social, psychological, and cultural reasoning about discrimination and other forms of trauma as determinants of health.

In the sections to follow, we describe the model's components, including Native women's health outcomes, the traumatic stressors they encounter, relationships between these stressors and health outcomes, and the stress-buffering role of cultural factors.

CONTEMPORARY HEALTH OF NATIVE WOMEN

There are few comprehensive reviews of Native women's health (e.g., Kauffman and Joseph-Fox1 and Joe11). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data spanning 1994 to 1998 indicate that rates for most of the top 10 causes of death among Native women are similar to or lower than rates among women of all races: major cardiovascular disease, 192.9 per 100 000 and 307.3, respectively; heart disease, 140.3 and 228.8; malignant neoplasms, 113.3 and 171.6; ischemic heart disease, 94.2 and 161.7; cerebrovascular disease, 40.1 and 59.6; lung cancer, 25.0 and 41.3; and pneumonia and influenza, 22.4 and 29.0.14

However, Native women have higher death rates due to diabetes (45.4 vs 22.4), all types of accidents combined (38.1 vs 22.0), motor vehicle accidents (22.7 vs 10.5), chronic liver disease and cirrhosis (20.5 vs 6.1), alcohol abuse (20.3 vs 3.5), and suicide (5.2 vs 4.4). Native women are second only to African American women in terms of death rates due to homicide (4.8 vs 9.0) and drug abuse (4.7 vs 4.8). Native women's ageadjusted cervical cancer death rate during the period 1994 to 1996 was 52% higher than the all-race rate in 1995 (3.8 vs. 2.5).10

The infant mortality rate for Natives residing within the 35-state IHS area is 22% higher than the overall US rate (9.3 vs 7.6 per 1000 live births).10 Factors related to this increased mortality include Native women's lower rates of prenatal care in the first trimester (18% lower than for all races combined), higher rates of alcohol consumption during pregnancy (3 times higher than for all races combined), and higher rates of tobacco use during pregnancy (1.5 times higher than for all races combined).10

The relatively low number of reported AIDS cases among Native women belies the many factors contributing to the increased vulnerability of these women to HIV infection.15 Moreover, problems associated with racial misclassification may result in serious underestimations of HIV rates among Native women.16,17 One study revealed that in 3 western states, HIV rates among third-trimester Native women were 4 to 8 times higher than rates among childbearing women of all other races.18 It has also been shown that Native female sexually transmitted disease patients in urban areas have HIV rates 1.5 times higher than their rural counterparts. Fisher and colleagues19 found that White men who had sex with both White and Alaska Native women were significantly less likely to use condoms with Alaska Native women.

High rates of psychiatric problems and related comorbidity have been reported in many Native communities (with frequency estimates ranging from 20%–63% of adult populations), often higher than rates exhibited by non-Native groups.20 Depression is among the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in Native communities,21 and it has been associated with living in urban areas and with substance abuse.22,23 Rates of cooccurrence of mental health problems and substance abuse problems are estimated to be as high as 80% among Natives.24

Although more than 60% of Natives live in urban settings, only a handful of studies provide any relevant data on the health-related concerns of such individuals, and none, to our knowledge, have focused specifically on women. It has been shown that there are higher rates of infant mortality, low birthweight, and alcohol- and injury-related mortality among urban Natives than among rural Natives.25 Furthermore, urban Native mothers have been shown to be 50% more likely than rural Native mothers to delay prenatal care or receive no such care. These data, along with the finding that only 2% of IHS funding serves urban communities, suggest that urban Natives are at a disproportionate risk for health-related problems.25,26

Absent a fourth world context, interpreting epidemiological data such as these leads to problematic interpretations of Native women's health statistics. As noted by Browne and Fiske,27 failure to account for socioenvironmental contexts can lead to pathologized perceptions of Natives, reinforce power inequities, and perpetuate paternalism and dependency in regard to health care.28 Many of the behavioral health problems (e.g., diabetes, alcoholism) of Native women are directly connected to their colonized status and to associated forms of environmental, institutional, and interpersonal discrimination.

For example, among Tohono O'Odham living within US boundaries, adult diabetes rates exceed 50%; however, their counterparts in Mexico, who have access to a traditional diet, have diabetes rates well below the national average. Other operative factors include environmental barriers such as inadequate transportation, limited availability and accessibility of services, institutionalized discrimination, and avoidance of health care systems that are not deemed culturally safe.27

TRAUMATIC LIFE STRESSORS

Natives are victims of violent crimes at an annual rate of 124 per 1000, more than 2.5 times the national average.7 Native women are disproportionately affected by violence at a rate almost 50% higher than that reported for African American males. In addition, the violent crime rate among Native women (98 per 1000) is higher than that among women of any other ethnic group. Furthermore, Natives are more likely than members of other racial groups to report interracial violence, and Native victims of sexual assault report that 90% of the assailants are African American or European American.

It has been shown that Native women are at increased risk of experiencing physical and sexual assault29–31 as well as child abuse and neglect.32 In fact, during 1992 to 1995, Natives and Asians were the only ethnic/racial groups to show increases in substantiated rates of child abuse or neglect of children younger than 15 years.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRAUMA AND HEALTH OUTCOMES

There is ample evidence of the effects of discrimination and different types of trauma on the health outcomes of non-Native populations. Discrimination has been related to psychological distress,33 global measures of distress,34 depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms,35 poor physical health, and high blood pressure.36 Recent evidence suggests that a combination of oppression and the chronic strains associated with multiple forms of discrimination may lead to more cumulative physical and mental health symptoms among people of color.37,38

Among women of color, perceptions of racism or gender-based discrimination have been related to increased stress,39 depression,33 psychological distress,40,41 hypertension,42 higher blood pressure levels,36 and decreased satisfaction with medical care.43 One study showed that invalidating encounters within mainstream health care systems and routinization in regard to service delivery affected the quality of care experienced by Native women and recapitulated daily discriminatory encounters endured by the women outside health care systems.27 Among Native female youths, discrimination has been found to be related to withdrawn behavior, anxiety, depression, and physical complaints related to stress.44

The high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)45,46 and other psychological distress experienced by Natives may be due to elevated rates of violence. However, historic traumas (e.g., boarding school exposure, coercive migration, and non-Native custodial care placements) must also be considered. Robin et al.46 presented data supporting the supposition that both specific trauma and cumulative trauma among Natives are significant factors in their high rates of substance use and abuse, traumatic depression, and PTSD. Along with their alcohol and sexual risk behavior, high rates of childhood abuse, unresolved grief and trauma, and PTSD may affect Native women's health.47,48

CULTURAL BUFFERS

Clearly, not every Native woman under stress develops health-related problems. What are the factors that might buffer or moderate the vulnerability of Native women? Research on urban Native samples has suggested that identity attitudes (i.e., the extent to which one internalizes or externalizes attitudes toward oneself and one's group) are important in enhancing self-esteem, coping with psychological distress, and avoiding depression.49 Likewise, Zimmerman and colleagues50 proposed that enculturation, or the process by which individuals learn about and identify with their minority culture, is a protective mechanism that can either mitigate the negative effects of stressors or enhance the effects of buffers, decreasing the probability of negative outcomes such as drinking problems.

Empirical studies have suggested that spiritual methods of coping are associated with psychological, social, and physical adjustment to stressful life events as well as with physical and mental health status.51 Moreover, it has been shown that spiritual coping continues to predict significant variance in outcomes even after control for the effects of nonspiritual coping measures and global religious measures.51,52 Finally, recent data suggest that immersion in traditional health practices (e.g., use of indigenous roots and teas) and healing practices (e.g., use of a sweat lodge in ritual purification) may have intrinsic benefits directly connected to positive health outcomes among Natives.53,54

CONCLUSION

The health problems of Native women are not simply an artifact of Native genetics, culture, or lifestyle. An examination of these women's sociodemographic vulnerabilities and fourth world context suggests that poverty, geography, racism, and discrimination undermine physical health and mental health outcomes, as they do among other marginalized populations. However, fourth world dynamics uniquely affect Native peoples living within the United States, and they may have distinctive effects on Native women's health. Precisely how historical and current traumas (e.g., unresolved grief and mourning related to loss of land and place and the negotiation of invisibility in urban settings) affect the health of Native populations has yet to be empirically documented. Within indigenous communities, however, these stressors are viewed as key factors related to health.

The model introduced here represents a preliminary attempt to articulate the stress and coping processes operating in the fourth world context of Native women. Importantly, the model highlights protective or buffering factors, in contrast to the focus on pathology that characterizes much of the research on Native peoples. Interpreting the vulnerabilities of Native women within the context of their historic and contemporary oppression while capitalizing on their strengths represents an indigenist perspective that will assist public health researchers and practitioners in promoting the individual health and well-being of these women and, ultimately, the health and well-being of indigenous communities and nations.

K. L. Walters made the major conceptual contributions and drafted the paper. K. L. Walters and J. M. Simoni jointly edited and revised the paper.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Kauffman JA, Joseph-Fox YK. American Indian and Alaska Native women. In: Bayne-Smith M, ed. Race, Gender, and Health. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1996:68–92.

- 2.Jaimes MA, Halsey T. Native American women. In: Jaimes MA, ed. The State of Native America. Boston, Mass: South End Press; 1992:311–344.

- 3.O'Neil J. The politics of health in the fourth world: a northern Canadian example. Hum Organ. 1986;45:119–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Churchill W. From a Native Son: Selected Essays on Indigenism, 1985–1995. Boston, Mass: South End Press; 1996.

- 5.Duran E, Duran B, Yellow Horse Brave Heart M, Yellow Horse-Davis S. Healing the American Indian soul wound. In: Danieli Y, ed. International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1998:341–354.

- 6.Braveheart-Jordan M, DeBruyn L. (1995). So she may walk in balance: integrating the impact of historical trauma in the treatment of Native American Indian women. In: Adelman J, Enguidanos GM, eds. Racism in the Lives of Women: Testimony, Theory, and Guides to Antiracist Practice. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 1995:345–368.

- 7.Greenfeld LA, Smith SK. American Indians and Crime. Washington, DC: US Dept of Justice; 1999.

- 8.HIV/AIDS and Native Americans. Washington, DC: National Minority AIDS Council; 1999.

- 9.1990 Census Counts of American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts, and American Indian and Alaska Native Areas. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 1991.

- 10.Regional Differences in Indian Health: 1998–1999. Rockville, Md: Indian Health Service; 1999.

- 11.Joe JR. The health of American Indian and Alaska Native women. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2000;51:141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinges NG, Joos SK. Stress, coping, and health: models of interaction for Indian and Native populations. Behav Health Issues Am Indians Alaska Natives. 1988;1:8–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv. 1999;29:295–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Death Rates and Number of Deaths by State, Race, Sex, Age, and Cause, 1994–1998. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001.

- 15.Walters KL, Simoni JM, Harris C. Patterns and predictors of HIV risk among urban American Indians. Am Indian Alaska Native Ment Health Res J. 2000;9(2):1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieb LE, Conway GA, Hedderman M, Yao J, Kerndt PR. Racial misclassification of American Indians with AIDS in Los Angeles County. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:1137–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowell RM, Bouey PD. Update on HIV/AIDS among American Indians and Alaska Natives. IHS Primary Care Provider. 1997;22(4):49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conway GA, Ambrose TJ, Chase E, et al. Infection in American Indians and Alaska Natives: surveys in the Indian Health Service. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:803–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher DG, Fenaughty AM, Pashcane DM, Cagle MS, Cagle HH. Alaska Native drug users and sexually transmitted disease: results of a five-year study. Am Indian Alaska Native Ment Health Res J. 2000;9(1):47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robin RW, Chester B, Rasmussen JK, Jaranson JM, Goldman D. Factors influencing utilization of mental health and substance abuse services by American Indian men and women. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:826–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beals J, Manson SM, Keane EM, Dick RW. Factorial structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale among American Indian college students. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:623–627. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curyto KJ, Chapleski EE, Lichtenberg PA, Hodges E, Kadzunski R, Sobeck J. Prevalence and prediction of depression in American Indian elderly. Clin Gerontologist. 1998;18(3):19–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalrymple AJ, O'Doherty JJ, Nietschei KM. Comparative analysis of Native admissions and registrations to northwestern Ontario treatment facilities: hospital and community sectors. Can J Psychiatry. 1995;40:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Provan KG, Carson LMP. Behavioral health funding for Native Americans in Arizona: policy implications for states and tribes. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2000;27:17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossman DC, Krieger JW, Sugarman JR, Forquera RA. Health status of urban American Indians and Alaska Natives. JAMA. 1994;271:845–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burhansstipanov L. Urban Native American health issues. Cancer. 2000;88(suppl 5):1207–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Browne AJ, Fiske J. First Nations women's encounters with mainstream health care services. West J Nurs Res. 2001;23:126–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Neil JD, Reading JR, Leader A. Changing the relations of surveillance: the development of a discourse of resistance in Aboriginal epidemiology. Hum Organ. 1998;57:230–237. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chester B, Robin RW, Koss M, Lopez J. Grandmother dishonored: violence against women by male partners in American Indian communities. Violence Vict. 1994;9:249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norton IM, Manson SM. A silent minority: battered American Indian women. J Fam Violence. 1995;10:307–318. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Old Dog Cross P. Sexual abuse: a new threat to the Native American woman: an overview. Listening Post. 1982;6(2):18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Child Abuse and Neglect in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities and the Role of the Indian Health Service. Washington, DC: National Indian Justice Center; 1990.

- 33.Salgado de Snyder SN. Factors associated with acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among married Mexican immigrant women. Psychol Women Q. 1987;11:457–488. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA study of young black and white women and men. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1370–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diaz RM, Ayala G. Social Discrimination and Health: The Case of Latino Gay Men and HIV Risk. Washington, DC: Policy Institute, National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2001.

- 38.Williams DR. Race and health: basic questions, emerging directions. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;7:322–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murrell NL. Stress, self-esteem, and racism: relationships with low birth weight and preterm delivery in African American women. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 1996;8:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amaro H, Russo NF, Johnson J. Family and work predictors of psychological well-being among Hispanic women professionals. Psychol Women Q. 1987;11:505–521. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mays VM, Cochran SD. Racial discrimination and health outcomes in African Americans. Paper presented at: Joint Meeting of the Public Health Conference on Records and Statistics and the Data Users Conference; July 1997; Washington, DC.

- 42.Krieger N. Racial and gender discrimination: risk factors for high blood pressure? Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:1273–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Auslander WF, Thompson S, Dreitzer D, Santiago JV. Mothers' satisfaction with medical care: perceptions of racism, family stress, and medical outcomes in children with diabetes. Health Soc Work. 1997;22:190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Simons RL, et al. Intergenerational continuity of parental rejection and depressed affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:1036–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manson S, Beals J, O'Nell T, et al. Wounded spirits, ailing hearts: PTSD and related disorders among American Indians. In: Marsella AJ, Friedman SJ, Gerrity ET, Scurfield RM, eds. Ethnocultural Aspects of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Issues, Research, and Clinical Applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1996:255–283.

- 46.Robin RW, Chester B, Goldman D. Cumulative trauma and PTSD in American Indian communities. In: Marsella AJ, Friedman NJ, Gerrity ET, Scurfield RM, eds. Ethnocultural Aspects of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Issues, Research, and Clinical Applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1996:239–254.

- 47.Walters KL, Simoni JM. Trauma, substance use, and HIV risk among urban American Indian women. Ethnic Minority Psychol. 1999;5:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stewart SH. Alcohol abuse among individuals exposed to trauma: a critical review. Psychol Bull. 1996;120:83–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walters KL. Urban American Indian identity attitudes and acculturative styles. J Hum Behav Soc Environment. 1999;2:163–178. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zimmerman MA, Washienko KM, Walter B, Dyer S. The development of a measure of enculturation for Native American youth. Am J Community Psychol. 1996;24:295–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pargament KI. Religious and spiritual coping. In: Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. Kalamazoo, Mich: Fetzer Institute; 1999:43–56.

- 52.Simoni JM, Kerwin JF, Martone MM. Spirituality and psychological adaptation among women with HIV/AIDS: implications for counseling. J Counseling Psychol. In press.

- 53.Buchwald D, Beals J, Manson SM. Use of traditional health practices among Native Americans in a primary care setting. Med Care. 2000;38:1191–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marbella AM, Harris MC, Diehr S, Ignace G, Ignace G. Use of Native American healers among Native American patients in an urban Native American health center. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]