Abstract

For many poor Americans, having a decent home and suitable living environment remains a dream. This lack of adequate housing is not only a burden for many of the poor, but it is harmful to the larger society as well, because of the adverse effects of inadequate housing on public health.

Not only is the failure to provide adequate housing shortsighted from a policy perspective, but it is also a failure to live up to societal obligations. There is a societal obligation to meet the housing needs of everyone, including the most disadvantaged. Housing assistance must become a federally-funded entitlement.

AMERICA HAS BOTH AN IMPLICIT and an explicit social contract to provide adequate housing for its entire population. To date, this is a contract whose obligations remain unfulfilled. Evidence of this failure abounds in the vast numbers of homeless families on city streets, in the large numbers of families that have to live doubled and even tripled up with other families, and in the crushingly high rent burdens that many low-income families have to endure. Less transparent but no less important are the pernicious effects of this unfulfilled contract on the health of the disadvantaged, as has been described elsewhere.1

THE CONTRACTUAL OBLIGATION

The explicit nature of the societal contract to meet the housing needs of all is spelled out in the Housing Act of 1949 (42 USC §§ 1441–1490r [1994]), which stipulates the “realization as soon as feasible of the goal of a decent home and suitable living environment for every American family.” But the Housing Act of 1949 was passed more than a half century ago by different politicians representing a different population. One could argue that this contract is no longer binding. Yet there is substantial evidence that the American polity still views a decent home as a minimal right in America. This is evidenced by the numerous state and local policies that mandate a minimal level of housing. As will be shown below, however, these mandates are insufficient to meet the housing needs of our most disadvantaged citizens.

Through the enactment of building codes and other regulations, we have deemed that housing below minimal standards is unacceptable and unfit for human occupation. The cost of producing housing that meets even minimal standards, however, is above what many low-income households can afford. Consequently, such households are priced out of the market in many places—owing, in part, to society's consensus that housing below a certain level is not acceptable.

Of course, most housing occupied by the poor, and by most other people, for that matter, is not new but previously occupied housing. But in many expensive urban centers even used housing is beyond the means of many low-income households. If maintenance costs required to keep housing from falling below standards exceed what lowincome families can afford to pay, landlords may try to upgrade their units to attract more affluent and profitable tenants, or they may simply walk away from the property. Both gentrification and abandonment may occur in low-income neighborhoods if low-income families lack the purchasing power to make the provision of affordable housing profitable to landlords.

Owing to transformations in technology, overseas competition, and other factors that are not completely understood, the American economy over the past few decades has increasingly bifurcated into a highly skilled and well-paid sector and a low-paying service sector.2 Jobs in the low-paying service sector often leave households without sufficient income to afford housing that meets even minimal standards. A growing proportion of the populace simply earn too little to afford what society deems decent housing.

Further exacerbating the affordable housing shortage is the enactment of exclusionary zoning policies by many suburban communities. These policies typically exclude multifamily units or require large parcels of land for each unit, driving up the price of housing and making it virtually impossible for affordable housing to be located in the community. Entire swaths of communities are off limits to the poor because of local land use policies.

The enactment of building codes and zoning policies is prima facie evidence that America has deemed a certain standard of housing a basic requirement of a civilized society. If this were not so, we would allow the poor and homeless to build shantytowns, as is done in many cities of the Third World. Yet simply legislating out of existence housing deemed unacceptable does nothing to ensure everyone access to housing. If we are going to mandate a certain quality of housing, we are obligated to provide everyone with the means to obtain that housing.

AN UNFULFILLED OBLIGATION

America has come nowhere close to meeting this obligation. Although great progress has been made in improving the physical condition of housing, significant problems remain. For example, recent surveys of housing stock indicate that approximately 7% of all households and 15% of all low-income renter households live in units with severe or moderate physical problems (defined as malfunctioning plumbing, heating, or electrical systems, dilapidated public areas, or inadequate maintenance).3 Moreover, some of these physical deficiencies have serious health consequences, most notably, lead paint poisoning and exposure to pathogens stemming from pests.

Affordability is an intransigent problem that we have not come close to solving. Because housing is the single largest expenditure for most households, housing affordability has the potential to affect all domains of life that are subject to cost constraints, including health. Crushingly high rent burdens leave poor families with little money for food, doctor's visits, or other necessities. Thus, households lacking affordable housing are vulnerable to diseases and illness associated with malnutrition and inadequate health care. Doubling or tripling up lead to overcrowding and having to navigate relationships with other families, which is stressful. In extreme cases, a lack of affordable housing can result in homelessness. As a substantial body of research attests, these types of psychological stressors can have a negative impact on health.4

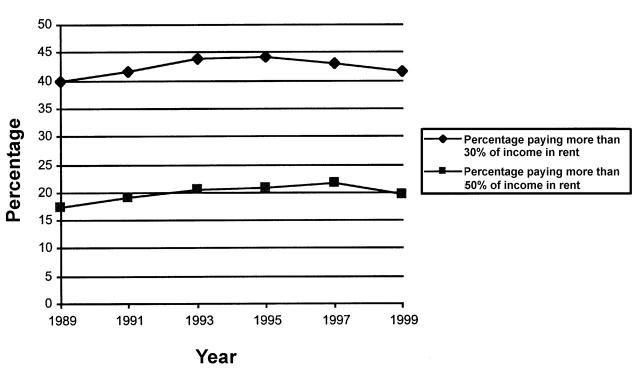

Despite the paramount importance of housing affordability, this front remains one where relatively little progress is being made. Indeed, by the rule of thumb that a household should devote no more than 30% of its income to housing, we may actually be losing ground. As Figure 1 ▶ illustrates, the proportion of all renters paying more than 30% in rent was higher in 1999 than it was in 1989. Even if we use a less stringent measure of affordability, the picture remains the same. In 1989, 17% of renters paid more than 50% of their income for rent; in 1999, 20% did. Thus, during the period of the longest economic boom in history scarcely any progress was made in the arena of affordable housing.

FIGURE 1—

Rent burdens in the United States, 1989–1999.

America, then, has an unfulfilled social obligation to adequately house all of its disadvantaged residents. This obligation grows out of the implicit agreement that no one should be forced to live in substandard housing. The failure to meet this obligation has an impact on the public's health.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

A housing policy designed to fulfill the social contract of providing decent housing for all would be funded at the federal level, as all redistributive programs should; would be funded at levels necessary to ensure that all those with needs could have their needs met, as others have advocated6; and would be sensitive to the conditions of local housing markets. Federal funding is most efficient and avoids the problem of localities' engaging in a race to the bottom, whereby each locality attempts to avoid attracting more poor households by providing overly generous housing benefits.

Making housing an entitlement would not only help meet the needs of all, but would be inherently more equitable than the current system. Affordable housing is now rationed, for the most part, on a first come, first served basis. There is nothing equitable about a system that provides some households with a subsidy worth up to the market rate for rental units in that area, while other equally deserving households receive nothing.

Finally, housing, as a relatively immobile good, cannot be redirected to places where needs emerge, the way food or financial capital can. Hence it makes sense for the federal government to redirect housing subsidies to areas experiencing the most need. Making housing assistance more sensitive to local housing conditions would target aid to localities most in need. To a certain extent this is already done through the use of “fair market rents,” which are based on the local market rate for similar units and are used to calculate the amount of assistance each family receives. But making housing assistance an entitlement would better target aid to cities with the most need.

Under present circumstances, a city with a dire affordable housing shortage and many families who cannot afford market rents does not necessarily receive more housing assistance than a city with less of a shortage, because the condition of the housing market plays only a minor role in determining where federal housing assistance is directed. This is in contrast to other entitlement programs, such as Medicaid or food stamps, in which resources automatically flow to localities with the most needy clients.

Moreover, the type of housing assistance needed in a locality will vary depending on the condition of the housing market. Tight housing markets may be more in need of newly constructed affordable housing, whereas markets where affordable units are abundant would be better served by housing vouchers.

The current direction of US housing policy is not particularly reassuring. Because the Bush administration has yet to articulate a clearly defined vision for affordable housing in urban America, the policies of the Clinton era have become the de facto policy orientation.

Under Clinton, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) attempted to change its image from that of a lumbering agency that indefinitely subsidized housing for low-income families in isolated ghettos to that of a more nimble and efficient agency that would provide its low-income clientele more choice but would also exact more obligations. Choice would come in the form of access to a greater variety of neighborhoods and an increase in opportunities to buy a home. Housing vouchers and counseling would be used to provide poor households with the means and information necessary to relocate to less poverty-stricken neighborhoods.

In addition, the low-income housing tax credit replaced public housing as the source of project-based housing assistance, with the federal government no longer building public housing and indeed demolishing some units. Recipients of HUD subsidies were also in some cases required to move toward self-sufficiency by developing a plan to earn sufficient income so that they would no longer need public subsidies.

While the pilot programs of many of these initiatives show signs of promise, the jury is still out on whether they can be expanded to encompass all of HUD's clientele. More importantly, from an affordable housing perspective, these innovations do not adequately address the shortage of affordable housing. The federal government currently provides assistance to approximately 4.6 million households, but roughly 9.7 million low-income households receive no housing assistance. Put another way, only about a third of all households in need of housing assistance receive it. Moreover, because housing assistance is not an entitlement, it is not as sensitive to local conditions as it could be, and resources do not automatically flow to localities with the greatest needs.

Thus, even if HUD's innovations to replace public housing with integration of low-income households into communities are successful beyond our wildest dreams, they would not help the majority of low-income households that need housing assistance but do not get it. Indeed, one policy innovation, which demolishes public housing and replaces the lost units with vouchers, may actually exacerbate the affordable housing shortage. Particularly in tight housing markets with low vacancy rates, the housing vouchers will not, in the short run, do anything to increase the supply of affordable housing. At best, current federal policy may be developing a more effective delivery system for a wholly inadequate remedy.

Addressing the remaining health-threatening physical deficiencies in the housing stock is largely a matter of mustering the political will to devote the necessary resources. For example, HUD's strategic plan of 2000 contained an initiative to eliminate lead hazards in approximately 2.3 million housing units, representing approximately 2% of the occupied housing stock, within 10 years. If successful, such an initiative would place the threat of lead poisoning in the dustbin of history. The fact that HUD could develop such a plan suggests that making serious progress concerning this problem is within the scope of current policy.

The example of lead paint poisoning aptly illustrates the progress made in combating the ills of poor housing and the work that remains to be done. The terrible housing conditions that once plagued many households have largely been eradicated; but a small yet significant number of households still live in physical conditions that may harm their health. It is surely within our power to eradicate the remaining problems.

Seriously addressing the issue of affordability would require a major expansion of resources devoted to affordable housing. Some estimates suggest HUD's budget would have to be doubled.6 The most equitable policy would be to treat affordable housing as an entitlement, rather than rationing it on a first come, first served basis as is done today. As daunting as this might seem initially, the logic behind expanding housing subsidies substantially is not that radical. Other needs, such as education, medical care, and food, are treated as entitlements; until recently income support was too. Even with the elimination of Aid to Families With Dependent Children as an entitlement, most states still treat it as such. Therefore, treating affordable housing as an entitlement would be consistent with most other public support programs.

CONCLUSION

If our goal is to improve the health of the most disadvantaged among us, it would be unwise to ignore the crisis of affordable housing. Poor physical conditions, affordability, and location are the 3 dimensions through which housing affects health. From a policy perspective, eliminating the few remaining physical housing problems that plague some of the poor is the most feasible task, and it is the domain where the most progress has been made.

The challenge of providing affordability is more daunting, but the logic is certainly there. We have entitlements for health, income, food, and education. Why not housing? This is also a place where social science might have a major impact. When light is shed on the links between affordable housing and health, the shortsightedness of neglecting housing only to incur higher medical costs later becomes clear. With regard to location, some progress has been made, but again, many low-income households are not receiving the financial assistance that would enable them to relocate.

Given the current political climate and the reemergence of budget deficits, the prospects for extending housing assistance to all those in need appear dim. Nevertheless, any effort to improve the health of the disadvantaged should include a major initiative to expand housing assistance. We will undoubtedly have to wait for a time when housing assistance will be an entitlement. But this is a wait that may be bad for our health.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Evans RG. Introduction. In: Evans RG, Barer ML, Marmor TR. Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not? The Determinants of Health of Populations. New York, NY: Aldine DeGruyter; 1994.

- 2.Levy F. The New Dollars and Dreams: American Incomes and Economic Change. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1998.

- 3.Strategic Plan FY2000–FY2006. Washington, DC: US Dept of Housing and Urban Development; 2000.

- 4.Dunn JR. Housing and health inequalities: review and prospects for research. Housing Studies. 2000;15:341–366. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Housing Survey. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/ahs.html. Accessed March 6, 2002.

- 6.Hartman C. The case for a right to housing. Housing Policy Debate. 1998;9:223–246. [Google Scholar]