Abstract

Objectives. This study examined factors associated with emergency department use among homeless and marginally housed persons.

Methods. Interviews were conducted with 2578 homeless and marginally housed persons, and factors associated with different patterns of emergency department use were assessed in multivariate models.

Results. Findings showed that 40.4% of respondents had 1 or more emergency department encounters in the previous year; 7.9% exhibited high rates of use (more than 3 visits) and accounted for 54.5% of all visits. Factors associated with high use rates included less stable housing, victimization, arrests, physical and mental illness, and substance abuse. Predisposing and need factors appeared to drive emergency department use.

Conclusions. Efforts to reduce emergency department use among the homeless should be targeted toward addressing underlying risk factors among those exhibiting high rates of use.

High rates of emergency department use create a strain on the health care system by leading to overcrowding,1,2 but they can also be seen as a marker of systemic problems, including poor access to nonemergency health care and the failure to prevent injuries and illnesses.3 A recent report noted increasing emergency department use nationwide, which contributes to overcrowding.4 Figures indicating high rates of use can reflect both a large proportion of people using the emergency department occasionally and a small proportion of people using it repeatedly. Among individuals without medical insurance or access to primary medical care, the emergency department can serve as the only available source of care.3,5,6 Population-based studies have shown that homeless persons have high rates of emergency department use; compared with the general population, the homeless are 3 times more likely to use an emergency department at least once in a year.7 Emergency department–based studies have also shown that homelessness is associated with repeated emergency department use.8,9

Homeless persons are at high risk for requiring emergency department services because of their elevated rates both of unintentional injuries and of traumatic injuries from assault10–12 and because of their poor health status and high rates of morbidity.11,13–16 Other factors commonly associated with homeless individuals' receipt of nonurgent medical care in emergency departments include lack of health insurance,17 lack of transportation,18 lack of a telephone,18 poor access to primary care,5,19,20 inner-city residence,3 minority status,20 chronic alcohol and drug abuse,21,22 and mental illness.10 These factors may contribute both to the high rates of emergency department use seen in homeless populations and to the association between homelessness and repeated use.

Although population-based studies of the homeless have revealed high rates of emergency department use, these studies have not examined repeated use among particular groups of individuals. Similarly, emergency department–based studies have demonstrated that homelessness is associated with repeated use but have not attempted to ascertain the proportions of homeless persons who exhibit repeated use or the factors associated with repeated use. We used a community-based survey of homeless and marginally housed persons in San Francisco to examine patterns of emergency department use, factors associated with use, and factors associated with repeated use.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

To survey a community-based population of homeless persons, we recruited individuals from homeless shelters and food lines. Because homeless persons are likely to spend part of their time in substandard housing, we also recruited individuals from low-rent, single-room-occupancy (SRO) hotels. Between April 1996 and December 1997, we recruited a sample of 2578 English-speaking adults. At that time, it was estimated that there were about 5000 literally homeless persons living on the street or in homeless shelters in San Francisco and between 6000 and 8000 persons residing in low-rent hotels in the area we studied.

The sampling design, which was based on a design developed by Burnam and Koegel,23 involved a multistage cluster sample with stratification into shelters, free meal programs, and SRO hotels in San Francisco. The shelter sample was drawn from all overnight shelters that housed at least 50 adults per night. The meal program sample included participants in 5 of 6 midday free-meal programs that served a minimum of 100 adults at least 3 days per week. SRO hotels were sampled, at a probability rate proportionate to size, from 292 low-cost residential hotels in census tracts located in the center of the city. Hotels eligible for inclusion were those that, according to the city's official list, had at least 20 “usually occupied” residential (nontourist) rooms licensed to rent for $400 per month or less.

Within each sampling site, individuals were recruited through the use of a systematic sampling design. Hotels that provided special in-house programs (e.g., health clinics or advocacy services) were excluded because of the possibility that health use practices among residents of such hotels are not representative. We also excluded respondents who appeared severely intoxicated or belligerent and those who were unable to provide informed consent. Respondents did not give their names or other identifying information; each respondent was assigned a unique identifier constructed from individual data to eliminate duplicate responses.

Interviews were conducted twice per month in community settings near each sampling site. Individuals were reimbursed either $10 (shelter or meal program recruits) or $15 (hotel recruits) for completing interviews. All participants underwent a 45-minute interview conducted by trained field staff using a standard questionnaire that involved a structured response format. All responses were selfreports with the exception of HIV status, which was determined through serological testing. Health service use was not validated with medical records.

Conceptual Framework

We used the behavioral model for vulnerable populations,24 an adaptation of Andersen's behavioral model,25 as the conceptual framework for our analysis. According to this model, people's use of health care is affected by predisposing, enabling, and need factors. We assessed the relationships between our outcomes of interest and (1) the predisposing factors of age, sex, ethnicity, education, housing status, criminal history, victimization, substance abuse, and mental illness; (2) the enabling factors of income, medical insurance, and receipt of public benefits; and (3) the need factors of self-reported health status, chronic illness, and HIV status. Some factors, such as victimization, mental illness, and substance abuse, can be seen as either predisposing factors (if they contribute to an individual's overall vulnerability) or need factors (if their presence is the proximate cause of receipt of health care).10,24

Health Service Use

Frequency and volume of emergency department encounters.

The primary outcome of interest was self-reported number of emergency department encounters in the previous 12 months. Respondents were asked to report any emergency department visit for any reason, including visits for psychiatric reasons. These responses were grouped into intensity categories representing 0, 1, 2 or 3, and 4 or more encounters. We computed the total number of emergency department encounters reported by all participants and estimated the percentage of total encounters attributable to each intensity level. We defined repeated use as 4 or more emergency department encounters in the past year.

Use of ambulatory care services.

Ambulatory care use was defined as any health care visit for the purpose of physical health in a non–emergency department, non-inpatient setting in the previous year. Number of contacts was not ascertained. We defined exclusive use of the emergency department in the previous year as emergency department use but no ambulatory care use.

Inpatient hospitalization.

Participants were asked whether they had spent the night in the hospital for a physical problem in the previous 12 months (nights spent in a psychiatric hospital, in an emergency department, or in a hospital lobby or waiting room were excluded).

Independent Variables

Predisposing factors.

Predisposing factors included age (less than 35, 35–50, more than 50 years), sex, ethnicity (White, African American, Latino, “other”), education (less than high school, high school or more), duration of homelessness (more than 1 year, “other”), housing status, mental illness and substance abuse, housing history, and history of victimization and arrests.

Trained interviewers used a residential calendar to assess the housing history of all respondents. Participants reported where they had spent each night during the previous week and month and then, through the use of key remembered events, estimated where they had spent nights during the past year. We considered participants who reported that they spent at least 90% of their nights in a hotel and spent no nights living on the street or in a shelter as “marginally housed.” All others were considered to be homeless.

Participants were asked whether they had been arrested in the past year. They were also asked whether they had been a victim of property theft, assault with robbery, physical assault, or sexual assault in the previous year. We included any such event as an episode of victimization.

We asked respondents whether they had a history of psychiatric hospitalization and whether they had ever used injection drugs. We also asked whether they had had a drug or alcohol problem in the past year; those who answered in the affirmative were considered to have a drug or alcohol problem.

Enabling factors.

We classified income as total monthly income from all benefits, earnings (legal and illegal), and panhandling or donations. Respondents were grouped according to whether they reported receiving Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance and according to their medical insurance status (uninsured, Medicaid or Medicare, veterans' insurance, other insurance).

Need factors.

Need factors included health status, chronic illnesses, and HIV status. Respondents were asked whether they considered their health to be excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. They were also asked whether a physician had ever told them that they had emphysema or chronic bronchitis, asthma, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, or stroke. Those who indicated that they had been diagnosed with at least 1 of these conditions were categorized as having a chronic medical condition. As mentioned earlier, HIV status was determined via serological testing.

Analysis

We examined factors associated with any emergency department encounter and with 4 or more encounters in the previous 12 months, defining the dependent variable dichotomously in each case. We also examined factors associated with the occurrence of at least 1 ambulatory care visit in the past year. Univariate associations were assessed with Student t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests (for continuous or ordinal terms) and with χ2 tests (for categorical terms). In separate models, we used stepwise logistic regression to characterize adjusted odd ratios for any emergency department encounter and for 4 or more encounters; candidate covariates were factors with a significance level below .25 as determined in univariate analyses (Table 1 ▶). We adjusted results of stepwise models for demographic characteristics (age, sex, and ethnicity) and other factors to display a common vector of covariates. We validated final models with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Participant Groups: San Francisco, 1996–1997

| Characteristic | All Participants (n = 2532) | Any ED Use (n = 1022) | ≥4 ED Encounters (n = 199) |

| Predisposing factors | |||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 43.3 (10.8) | 42.0 (10.0)*** | 41.7 (9.2)** |

| Age, y, no. (%) | |||

| < 35 | 498 (19.7) | 225 (22.0) | 41 (20.6) |

| 35–50 | 1479 (58.4) | 609 (59.6) | 126 (63.3) |

| > 50 | 555 (21.9) | 188 (18.4) | 32 (16.1) |

| Male, no. (%) | 1967 (77.7) | 751 (73.5)*** | 138 (69.4)*** |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | |||

| White | 988 (39.0) | 454 (44.4)*** | 87 (43.7)* |

| African American | 1122 (44.3) | 426 (41.7)** | 77 (38.7)* |

| Latino | 136 (5.4) | 41 (4.0) | 9 (4.5) |

| Other | 286 (11.3) | 101 (9.9) | 26 (13.1) |

| Did not complete high school, no. (%) | 667 (26.3) | 268 (26.2) | 56 (28.1) |

| Veteran | 600 (23.7) | 226 (22.1)* | 41 (20.6) |

| Housing history | |||

| Homeless more than 1 year, no. (%) | 1008 (39.8) | 433 (42.4)** | 104 (52.3)*** |

| Nights on street, mean (median) | 88 (12) | 96 (30)*** | 107 (46)*** |

| Marginally housed, no. (%) | 589 (23.3) | 171 (16.7)*** | 21 (10.6)*** |

| Enabling factors | |||

| Monthly income | |||

| All sources, mean $ (median) | 631 (500) | 631 (545) | 624 (576) |

| SSI or SSDI, no. (%) | 710 (28.0) | 315 (30.8)** | 73 (36.7)*** |

| Health insurance, no. (%) | |||

| Medicaid or Medicare | 891 (35.2) | 398 (38.9)*** | 96 (48.2)*** |

| Veterans' insurance | 337 (13.3) | 123 (12.0) | 24 (12.1) |

| Other | 163 (6.4) | 71 (7.0) | 8 (4.0) |

| Uninsured | 1322 (52.2) | 516 (50.5)* | 87 (43.7)** |

| Predisposing/need factors | |||

| Crime/victimization, no. (%) | |||

| Arrested in past year | 735 (29.0) | 373 (36.5)*** | 86 (43.2)*** |

| Crime victim in past year | 1447 (57.2) | 729 (71.3)*** | 159 (79.9)*** |

| Mental health/substance abuse, no. (%) | |||

| Mental health inpatient (lifetime) | 564 (22.3) | 282 (27.6)*** | 75 (37.7)*** |

| Drug or alcohol problem in past year | 1218 (48.1) | 549 (53.7)*** | 125 (62.8)*** |

| Need factors, no. (%) | |||

| General health | |||

| Excellent/very good | 886 (35.0) | 291 (28.5) | 39 (19.6) |

| Good | 766 (30.3) | 277 (27.1) | 45 (22.6) |

| Fair/poor | 880 (34.8) | 454 (44.4)*** | 115 (57.8)*** |

| HIV positive | 217 (8.6) | 91 (8.9) | 15 (7.5) |

| Medical comorbidity | 703 (27.8) | 376 (36.8)*** | 103 (51.8)*** |

Note. See text for descriptions of variables. ED = emergency department; SSI = Social Security Income; SSDI = Social Security Disability Insurance.

*.05 < P < .20; **.01 < P < .05; ***P < .01 (vs other respondents in bivariate logistic regression).

RESULTS

A total of 2578 individuals completed the questionnaire (two thirds of those approached agreed to participate). Forty-six responses were excluded on the basis of missing data; 2532 (98.2%) questionnaires were included in the analysis. There were no significant differences between respondents and nonrespondents in terms of sex, race, or ethnicity.

Predisposing Factors

More than three quarters of the respondents were men; the mean reported age was 43 years (range: 15–77 years). Respondents were predominantly White (39.0%) and African American (44.3%; Table 1 ▶).

Housing status.

Forty percent of the respondents reported having been homeless for more than a year. Respondents had spent a mean number of 88 days living on the street or in a shelter in the previous year. One fifth (20.5%) reported spending most of the past year living on the street or in a shelter. In addition, 589 respondents (23.3%) reported spending at least 90% of the days in the past year living in a hotel and spending no nights on the street or in a shelter; thus, they were classified as marginally housed.

Crime and victimization.

Almost a quarter of the respondents (22.6%) reported ever having spent time in prison. Twenty-nine percent had been arrested in the previous year, and more than half (57.2%) had been a victim of crime in that period.

Mental illness and substance abuse.

Almost a quarter of the respondents reported a history of psychiatric hospitalization, and 41.7% reported ever having used injection drugs. Almost half (48.1%) considered themselves to have had a drug or alcohol problem in the past year.

Enabling Factors

Overall mean monthly income was $631. Almost 85% of respondents reported a formal source of monthly income, such as state general assistance (39.4%), Social Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance (28.0%), a job (19.9%), or veterans' benefits (2.3%). Of respondents with formal incomes, 41.4% also reported casual sources, including selling bottles and cans, help from family or friends, selling drugs, and sex work; 392 (15.0%) respondents had only casual sources of income. In all, 1322 respondents (52.2%) were medically uninsured; 35.2% had Medicaid or Medicare insurance, and 13.3% had veterans' insurance.

Need Factors

More than a quarter of the respondents (27.8%) reported having at least 1 of the 5 chronic health problems assessed (heart disease or stroke, high blood pressure, asthma, diabetes, or chronic bronchitis/emphysema). More than a third (34.8%) reported their health status as fair or poor. According to serological testing, 8.6% of the respondents were HIV positive.

Health Care Use

Emergency department use.

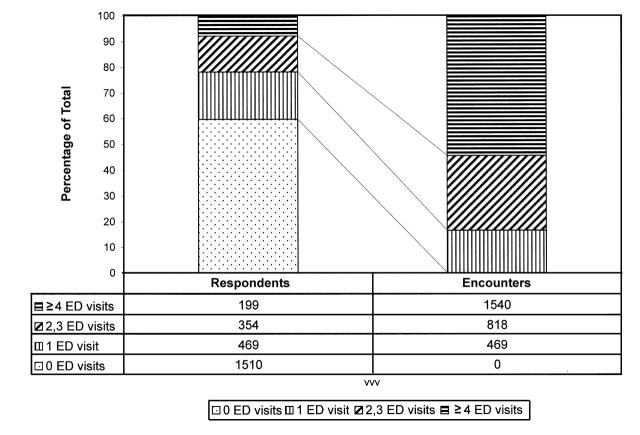

Among the respondents, 1022 (40.4%) reported that they had received care in an emergency department in the previous year (Table 2 ▶). Almost a fifth (18.5%) reported having had 1 emergency department visit in the past year, 14.0% reported 2 or 3 visits, and 7.9% reported 4 or more visits (Figure 1 ▶). In terms of exclusive use, 18.4% of all respondents reported receiving outpatient care only in an emergency department in the past year; 45.6% of all emergency department users were exclusive users.

TABLE 2—

Health Service Encounters in the Previous 12 Months Among Homeless and Marginally Housed Individuals (n = 2532): San Francisco, 1996–1997

| Encounter | Sample, No. (%) |

| Any ED use | 1022 (40.4%) |

| No. of ED visits | |

| 0 | 1510 (59.6) |

| 1 | 469 (18.5) |

| 2–3 | 354 (14.0) |

| ≥4 | 199 (7.9) |

| Any ambulatory (non-ED) care | 1171 (46.3) |

| Inpatient hospitalization for physical illness | 367 (14.5) |

Note. ED = emergency department.

FIGURE 1—

Frequency and volume of emergency department (ED) encounters in a 12-month period among homeless and marginally housed individuals (n = 2532): San Francisco, 1996–1997.

In a multivariate analysis of all respondents, factors associated with any use of an emergency department in the past year included the following: younger age, female sex, White ethnicity, less stable housing (being homeless as opposed to marginally housed), worse health status (having medical comorbidities or being in fair or poor health), Medicaid or Medicare insurance (as compared with no insurance), and involvement with crime (as either a victim or a perpetrator). There was a trend toward an association between a history of psychiatric hospitalization and emergency department use, but this relationship was not significant. Neither substance abuse nor HIV status was associated with emergency department use (Table 3 ▶).

TABLE 3—

Multivariate Factors Associated With Emergency Department (ED) Use in the Previous 12 Months Among Homeless and Marginally Housed Individuals: San Francisco, 1996–1997

| Any ED visits (n = 1022) | 4 or More ED Visits (n = 199)a | |||||

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P |

| Age (10-year increase) | 0.84 | 0.77, 0.92 | < .01 | 0.86 | 0.73, 1.01 | .06 |

| Male | 0.76 | 0.62, 0.94 | < .01 | 0.77 | 0.55, 1.09 | .14 |

| Ethnicity | < .01 | .33 | ||||

| White | . . . | . . . | ||||

| African American | 0.76 | 0.63, 0.92 | < .01 | 0.81 | 0.58, 1.14 | .23 |

| Latino | 0.47 | 0.31, 0.72 | < .01 | 0.62 | 0.29, 1.33 | .22 |

| Other | 0.68 | 0.51, 0.92 | .01 | 1.12 | 0.69, 1.84 | .64 |

| Marginally housed | 0.61 | 0.49, 0.76 | < .01 | 0.42 | 0.26, 0.69 | < .01 |

| Medicaid/Medicare insurance (reference: uninsured) | 1.24 | 1.02, 1.51 | .03 | 1.49 | 1.07, 2.07 | .02 |

| Medical Comorbidity | 1.94 | 1.59, 2.37 | < .01 | 2.57 | 1.86, 3.55 | < .01 |

| Health status fair/poor (reference: good to excellent) | 1.74 | 1.44, 2.1 | < .01 | 2.01 | 1.45, 2.78 | < .01 |

| Alcohol/drug problem in past 12 months | 1.10 | 0.92, 1.32 | .28 | 1.41 | 1.02, 1.94 | .04 |

| History of psychiatric hospitalization | 1.20 | 0.97, 1.48 | .09 | 1.53 | 1.10, 2.14 | .01 |

| Arrested in previous 12 months | 1.53 | 1.27, 1.86 | < .01 | 1.65 | 1.19, 2.28 | < .01 |

| Crime victim | 2.24 | 1.87, 2.68 | < .01 | 2.26 | 1.55, 3.28 | < .01 |

aReference is 3 or fewer ED visits.

Repeated use.

The 199 respondents (7.9%) who reported 4 or more emergency department visits in the previous year accounted for 55% of all visits reported (Figure 1 ▶). In a multivariate model comparing respondents with 4 or more visits and those with 3 or fewer visits in the previous year (Table 3 ▶), the following factors were associated with repeated use: younger age, female sex, less stable housing (homeless vs marginally housed), Medicaid or Medicare insurance (vs no insurance), poorer health status (comorbid illness or fair or poor health), involvement in crime (as either perpetrator or victim), mental illness (history of psychiatric hospitalization), and substance abuse (drug or alcohol problem).

Other encounters.

Almost half (46.3%) of the respondents reported at least 1 ambulatory care visit in the previous year. Among people who did not use the emergency department, fewer than half (40.7%) reported an ambulatory care visit. Among those with any emergency department use, more than half (54.4%) reported such a visit. Finally, among those exhibiting a high rate of use, 59.8% reported an ambulatory care visit. In a multivariate model examining factors associated with making at least 1 ambulatory care visit in the past year (n = 1171; model not shown), older persons, those with higher incomes, crime victims, those in fair or poor health, and those with medical comorbidities were more likely to have made at least 1 such visit. African Americans were less likely to have made an ambulatory care visit.

Whereas insurance status was associated with ambulatory episodes in the univariate analysis, there was no such association in the multivariate model. More than a third (34.6%) of the overall sample had had no contact with a physician (emergency department, ambulatory care, or inpatient care) in the past year. Overall, 361 (14%) respondents reported at least 1 inpatient stay for physical illness in the previous 12 months. Among the 199 respondents with 4 or more emergency department visits, 56.4% (n = 114) had been hospitalized at least once.

DISCUSSION

In this community-based sample of homeless and marginally housed persons, we found that 40% had used an emergency department at least once in the previous year, a rate 3 times the US norm.4 However, it was the persons classified as repeated users (i.e., 4 or more emergency department encounters in the past year)—less than 8% of the total sample—who accounted for the majority of the total emergency department use. Concerns about emergency department overcrowding have led to a focus on reduction of use among the homeless.9 Our study suggests that such efforts should be targeted specifically toward homeless individuals who exhibit repeated emergency department use, given that these individuals account for a disproportionate amount of emergency department use.

Predisposing and need factors—less stable housing, chronic medical illness, and victimization—predominated in our models of emergency department use. The majority of our respondents exhibited high levels of housing instability, spending, on average, 3 months a year on the street or in shelters. Respondents who were marginally housed, spending almost all of their nights in SRO hotels and none in the street, were significantly less likely to use the emergency department or to be repeated users. Previous research has linked housing instability with more use of ambulatory care and less use of acute care services.7,26,27 This study adds support to such findings. The effects of lack of housing, which include exposure to violence, problems in managing chronic medical conditions, and difficulty in planning for health care, may increase emergency department use.

Much has been written about the overrepresentation of homeless persons among users of emergency departments.9,28 Our study suggests that the homeless do access emergency departments in large numbers but that they may not have their medical needs met in other forums. Almost half of those who used an emergency department used it as their only source of health care, and half of those who received care in nonemergency ambulatory care settings also used the emergency department. This suggests that the features of, and services offered by, emergency departments (e.g., accessibility at all hours of the day, availability of care without an appointment, treatment of acute injuries and severe illnesses) may encourage greater use. The predominance of need factors in our models supports previous research suggesting that homeless people use emergency departments according to medical need.10

Acute injuries are an important predictor of emergency department use by the homeless.10 In the present study, victimization was highly associated with exclusive emergency department use, any use, and repeated use. Victimization is ordinarily considered a predisposing factor; if it is the proximate cause of emergency department use, however, it can also be considered a need factor.10 Injuries caused by victimization may not be amenable to treatment in the primary care setting, in that they demand urgent attention, may occur when primary care is not available, and may require services not available at nonemergency ambulatory care sites.

An important finding of our study was that public health insurance was associated with higher rates of emergency department use. Contrary to findings in an earlier national study of homeless persons,7 insurance was not independently associated with ambulatory care in the present study. The reason may be that San Francisco has an extensive system of health care for the uninsured and homeless. The city's network of federally funded community health centers and integrated system of public health care services include 13 clinics funded by the department of public health, a public nursing home, and a public hospital. There are also a variety of clinics and outreach services specifically targeted to homeless persons.

In our sample, in which there was a broader penetration of public insurance among disabled individuals, insurance may have been a marker for higher levels of physical and mental disability. Further work is needed to more fully explore the complex interaction of health insurance status, emergency department use, and ambulatory care use patterns in this population.

Homeless individuals with repeated emergency department use represent an extreme example of the complications of homelessness. Many of the same factors that are associated with any emergency department use are associated with repeated use: poorer health, less stable housing, and involvement in crime. In the present study, however, individuals exhibiting high use rates were more likely than the total population of homeless ED users to have substance abuse and mental health problems. Because psychiatric emergency department visits were included in our measure of use, it is possible that mental illness and substance abuse represent need factors and lead directly to use of emergency departments.

This study involved several limitations. All responses were self-reports without medical record validation. Previous studies have shown that homeless persons are not significantly less accurate in reporting health care use than the general population, although they may be less accurate in reporting frequency of use.27,29 We did not have information on frequency of ambulatory care visits or on whether these visits signaled the presence of a regular provider. It is possible that ambulatory care, as assessed in the present study, does not represent health care received from a primary care provider with whom a patient has a continuous relationship.

In addition, we had no way of assessing whether the emergency department visits that were reported represented appropriate use or whether problems could have been addressed in nonemergency settings. Because of its extensive range of available health care services for the uninsured and homeless, San Francisco may not be representative of other urban centers. Finally, this study was cross sectional; we do not know whether the associations we found are causal. The same factors that lead people to be more stably housed may enable them to access ambulatory care and decrease their use of emergency departments.

One of the strengths of our study was that respondents were drawn from a community sample, and we were able to gather information on both those with and those without access to the health care system. In addition, detailed information about residential history allowed us both to include and to differentiate between those who used residential hotels intermittently and those who lived stably in residential hotels.

This study raises questions about the limits of medical interventions (e.g., provision of insurance or ambulatory care) designed to decrease emergency department use among homeless persons. Addressing the needs of homeless individuals who exhibit repeated emergency department use represents a particular challenge but may lead to the greatest reductions in use. The high rates of hospitalization and comparatively extensive use of ambulatory care among those demonstrating repeated emergency department use support the hypothesis that need for services drives homeless individuals' use of emergency departments.

Interventions providing health insurance or ambulatory care alternatives may not, on their own, be able to decrease emergency department use. The finding that those who live stably in residential hotels use fewer emergency department services suggests that provision of housing, particularly to the small proportion of homeless individuals who exhibit repeated use, may help decrease reliance on emergency departments and improve health care outcomes. This policy option merits further exploration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant 55729 and National Institute of Mental Health grant 54907. David Bangsberg's work was supported in part by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Margot B. Kushel's work was supported in part by a faculty development grant (5f D08 HP 50109) from the US Department of Health and Human Services. The University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research approved the study.

We thank Marjorie Robertson, PhD, for acting as study director during the data collection period and for supervising work on study design and implementation, instrument development, field work implementation, and initial data management.

Peer Reviewed

M. B. Kushel was responsible for the study design; she participated in the analysis and was responsible for the interpretation of the data and the drafting and final revision of the manuscript. S. Perry was responsible for data management, conducted and assisted in the interpretation of the analysis, and participated in the revision of the manuscript. D. Bangsberg assisted with the study design, interpretation, and revision of the manuscript. R. Clark participated in the study design, in data collection, and in revision of the manuscript. A. R. Moss conceived of the study; supervised the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; and participated in revision of manuscript.

References

- 1.Richards JR, Navarro ML, Derlet RW. Survey of directors of emergency departments in California on overcrowding. West J Med. 2000;172:385–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derlet R, Richards J, Kravitz R. Frequent overcrowding in US emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyrance PH Jr, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. US emergency department costs: no emergency. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1527–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1999 Emergency Department Summary. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. Report 320.

- 5.Grumbach K, Keane D, Bindman A. Primary care and public emergency department overcrowding. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:372–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Medicaid Access Study Group. Access of Medicaid recipients to outpatient care. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1426–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA. 2001;285:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, et al. The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandelberg JH, Kuhn RE, Kohn MA. Epidemiologic analysis of an urban, public emergency department's frequent users. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:637–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padgett DK, Struening EL, Andrews H, Pittman J. Predictors of emergency room use by homeless adults in New York City: the influence of predisposing, enabling and need factors. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brickner PW, Scanlan BC, Conanan B, et al. Homeless persons and health care. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:405–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padgett DK, Struening EL. Victimization and traumatic injuries among the homeless: associations with alcohol, drug, and mental problems. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1992;62:525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang SW, Lebow JM, Bierer MF, O'Connell JJ, Orav EJ, Brennan TA. Risk factors for death in homeless adults in Boston. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1454–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. JAMA. 2000;283:2152–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O'Connell JJ, Lebow JM, Brennan TA. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hibbs JR, Benner L, Klugman L, et al. Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker DW, Stevens CD, Brook RH. Determinants of emergency department use: are race and ethnicity important? Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:677–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rask KJ, Williams MV, Parker RM, McNagny SE. Obstacles predicting lack of a regular provider and delays in seeking care for patients at an urban public hospital. JAMA. 1994;271:1931–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill JM, Mainous AG III, Nsereko M. The effect of continuity of care on emergency department use. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker DW, Stevens CD, Brook RH. Regular source of ambulatory care and medical care utilization by patients presenting to a public hospital emergency department. JAMA. 1994;271:1909–1912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGeary KA, French MT. Illicit drug use and emergency room utilization. Health Serv Res. 2000;35:153–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cherpitel CJ. Drinking patterns and problems, drug use and health services utilization: a comparison of two regions in the US general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;53:231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnam MA, Koegel P. Methodology for obtaining a representative sample of homeless persons: the Los Angeles Skid Row Study. Eval Rev. 1988;12:117–152. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34:1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duchon LM, Weitzman BC, Shinn M. The relationship of residential instability to medical care utilization among poor mothers in New York City. Med Care. 1999;37:1282–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Toole TP, Gibbon JL, Hanusa BH, Fine MJ. Utilization of health care services among subgroups of urban homeless and housed poor. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1999;24:91–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padgett DK, Brodsky B. Psychosocial factors influencing non-urgent use of the emergency room: a review of the literature and recommendations for research and improved service delivery. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelberg L, Siecke N. Accuracy of homeless adults' self-reports. Med Care. 1997;35:287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]