Abstract

Objectives. This study estimated national prevalence rates of medication noncompliance due to cost and resulting health problems among adults with disabilities.

Methods. Analyses involved 25 805 respondents to the Disability Follow-Back Survey, a supplement to the 1994 and 1995 National Health Interview Surveys.

Results. Findings showed that about 1.3 million adults with disabilities did not take their medications as prescribed because of cost, and more than half reported health problems as a result. Severe disability, poor health, low income, lack of insurance, and a high number of prescriptions increased the odds of being noncompliant as a result of cost.

Conclusions. Prescription noncompliance due to cost is a serious problem for many adults with chronic disease or disability. Most would not be helped by any of the current proposals to expand Medicare drug coverage.

Medicare prescription drug insurance is a recurrent focus of American health policy,1 and a combination of rapidly escalating drug costs2 and insurance industry trends3,4 have again thrust the issue to center stage. One of the more compelling rationales offered for expanding drug coverage is that affordability problems have clinical as well as economic consequences; that is, patients who have difficulty paying for medications are less likely to take them and can suffer adverse health effects as a result of noncompliance.5,6 Although this argument has intuitive appeal, no national data are available on cost-associated noncompliance, leading commentators to question both the scope of affordability problems and the remedies proposed to address them.7 In the present study, we sought to illuminate a critical aspect of the policy debate by developing the first national prevalence estimates of prescription noncompliance due to cost and resulting health problems among adults with disabilities, a population known to be heavy users of health care,8,9 including prescription drugs.9–11

Medicare recipients with drug coverage are more likely to fill their prescriptions than those without coverage.12–14 Total and out-of-pocket drug costs are heavily skewed toward individuals with poor health or chronic conditions, even among recipients with drug coverage.15 Noncompliance with prescription regimens is a widely recognized clinical problem,16 particularly in the case of treatment of chronic illnesses such as hypertension,17 and it has been identified as an important predictor of emergency room visits18 and hospital admissions.19,20 Numerous studies have linked rates of noncompliance to (1) sociodemographic factors, including age,21–23 sex,17 and race/ethnicity24; (2) socioeconomic factors, including insurance coverage25 and out-of-pocket costs18,19; and (3) treatment factors, including type26 and number of drugs prescribed27 and complexity of drug regimen.21 We examined the relative influences of these factors on self-reported noncompliance due to cost.

METHODS

Data Source

The Disability Supplement and the Disability Follow-Back Survey (DFS) are special supplements to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), a continuing probability survey of households representative of the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the United States.28 The Disability Supplement was administered to all respondents at the same time they completed the 1994 and 1995 NHIS core surveys. The DFS was administered 6 to 18 months later to respondents who reported impairments, functional limitations, chronic conditions, or receipt of disability benefits in the core NHIS surveys or the Disability Supplement.29 We used data from the adult supplement, which was administered to 25 805 respondents 18 years or older with disabilities (about 17% of the NHIS sample).

Adults selected for the DFS differed from the general population selected for the NHIS in predictable ways. They were older (according to weighted estimates, 35% of DFS adult respondents were 65 years or older, compared with 13% of NHIS adult respondents), had lower incomes (19% of DFS respondents had incomes at or below the poverty level, compared with 12% of NHIS respondents), and were in worse health (69% of DFS adult respondents rated their health as fair or poor, compared with 34% of NHIS respondents).

Data Analysis

We used a case–control design to examine risk factors associated with prescription noncompliance due to cost. We weighted all data so that they would be generalizable to the overall US population. SUDAAN statistical software was used to account for the clustered sample design of the NHIS and the lack of independence in the error terms.30 Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for demographic (age, sex, race/ethnicity), socioeconomic (income, health insurance coverage), and health and disability (self-assessed health status, severity of activity limitations, number of prescriptions) factors. Respondents who were not prescribed any medications and those who reported that they did not take their medications as prescribed for reasons other than cost were omitted from comparisons.

RESULTS

Almost 70% of the disabled adult population—about 28 million people—reported having been prescribed 1 or more medications (Table 1 ▶), and more than 85% of this group indicated that they always used their medications as prescribed. However, an estimated 3.8 million adults reported that they did not always use their medications as prescribed. These respondents were asked to select 1 or more of 8 reasons for their noncompliance (Table 2 ▶). About 1.3 million adults with disabilities cited 1 or more concerns related to cost (i.e., they did not get their prescription filled, did not fill their prescription completely, did not refill their prescription, or used their medicine less often than prescribed because of cost). This subset of noncompliant respondents was the focus of all subsequent analyses.

TABLE 1.

—Self-Reported Number of Prescriptions and Compliance Rates Among US Adults With Disabilities

| Estimated No. (%) | |

| Medications prescribed | |

| None | 12 161 (30.0) |

| 1–2 | 12 400 (30.6) |

| 3–5 | 10 846 (26.8) |

| 6–9 | 3 961 (9.8) |

| ≥10 | 1 139 (2.8) |

| Take medicine(s) as prescribeda | |

| All of the time | 24 762 (86.8) |

| Most of the time | 2 576 (9.0) |

| Some of the time | 793 (2.8) |

| Rarely | 210 (0.7) |

| Never | 194 (0.7) |

Note. Data are population estimates in 1000s derived from the National Center for Health Statistics. 29

aAbout 2% of people who had one or more prescriptions (317 respondents) selected the “don't know” response and were omitted from subsequent analyses.

TABLE 2.

—Reasons Given by Adults With Disabilities for Noncompliance

| Estimated No. (%) | |

| Affordability | 1280 (33.9) |

| Did not refill when ran out owing to cost | 898 (23.7) |

| Use less often than prescribed to stretch out owing to cost | 853 (22.6) |

| Did not get when first prescribed owing to cost | 767 (20.2) |

| Did not get entire prescription filled owing to cost | 741 (19.5) |

| Other | 2483 (65.8) |

| Sometimes forget to use | 1789 (47.4) |

| Don't use as prescribed because of side effects | 926 (24.5) |

| Don't use because of perceived lack of need | 826 (22.0) |

| Cannot pick up from drug store or get delivered | 125 (3.3) |

| Total noncomplianta | 3798 (100) |

Note. Data are population estimates in 1000s derived from the National Center for Health Statistics.29

aCurrently prescribed one or more medications and does not always take as prescribed.

Table 3 ▶ identifies specific factors associated with prescription noncompliance due to cost. Persons with incomes below the poverty level were at higher risk for cost-associated noncompliance than were persons with incomes above the poverty level (OR = 1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.3, 2.0). Uninsured adults were nearly 4 times as likely to be noncompliant owing to cost as their counterparts with private insurance (OR = 3.9; 95% CI = 3.0, 5.1). Adults with private and public health insurance (i.e., supplemental Medicare coverage) exhibited relatively low rates of cost-associated noncompliance (OR = 0.7; 95% CI = 0.5, 1.0).

TABLE 3.

—Factors Associated With Prescription Noncompliance due to Cost Among Adults With Disabilities

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

| Estimated No.a(n = 25 836) | Noncompliant due to Cost, % | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–34 | 2 787 | 20.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 35–44 | 3 342 | 10.8 | 0.99 | 0.77, 1.27 | 0.95 | 0.73, 1.25 |

| 45–54 | 4 022 | 7.1 | 0.62 | 0.49, 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.45, 0.78 |

| 55–64 | 4 413 | 3.6 | 0.30 | 0.23, 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.20, 0.38 |

| 65–74 | 5 733 | 2.1 | 0.17 | 0.13, 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.14, 0.32 |

| ≥75 | 5 539 | 0.9 | 0.08 | 0.05, 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.07, 0.16 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 10 118 | 4.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 15 718 | 5.4 | 1.30 | 1.10, 1.53 | 1.20 | 0.99, 1.44 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 20 481 | 4.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Hispanic | 1 695 | 3.7 | 0.75 | 0.57, 0.99 | 0.45 | 0.32, 0.64 |

| Black | 2 999 | 6.4 | 1.32 | 1.05, 1.67 | 0.87 | 0.65, 1.15 |

| Other | 662 | 4.1 | 0.84 | 0.47, 1.50 | 0.80 | 0.43, 1.47 |

| Income at or below poverty levelb | ||||||

| No | 19 137 | 4.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 4 167 | 8.8 | 2.34 | 1.94, 2.82 | 1.59 | 1.26, 2.02 |

| Health insurancec | ||||||

| Private only | 6 993 | 5.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Public only | 7 787 | 5.3 | 1.02 | 0.83, 1.26 | 1.02 | 0.77, 1.34 |

| Mix of private and public | 9 409 | 1.6 | 0.30 | 0.23, 0.39 | 0.70 | 0.49, 0.98 |

| Uninsured | 1 548 | 21.3 | 4.90 | 3.87, 6.20 | 3.90 | 3.02, 5.05 |

| Health status | ||||||

| Excellent–good | 13 863 | 7.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Fair–poor | 11 782 | 6.0 | 1.53 | 1.31, 1.80 | 1.39 | 1.13, 1.72 |

| Severity of disabilityd | ||||||

| No activity limitations | 11 282 | 4.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Activity limit only | 3 416 | 7.7 | 1.91 | 1.54, 2.37 | 1.93 | 1.48, 2.50 |

| Assistance needed | 11 138 | 4.9 | 1.18 | 0.98, 1.43 | 1.28 | 1.01, 1.63 |

| No. of prescriptions | ||||||

| 1–2 | 11 112 | 4.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 3–5 | 9 970 | 4.8 | 0.98 | 0.82, 1.17 | 1.37 | 1.11, 1.71 |

| ≥6 | 4 751 | 10.6 | 1.03 | 0.81, 1.32 | 1.62 | 1.19, 2.19 |

Note. Data are population estimates in 1000s derived from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).29 OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

aTotal includes adults with disabilities who always took their medications as prescribed, plus adults with disabilities who did not take their medications as prescribed owing to cost concerns (respondents who were noncompliant solely for other reasons, as well as those who were not prescribed any medications, were omitted from this analysis).

bFamily income data were missing for an estimated 9.8% of respondents and deleted in the multivariate model.

cHealth insurance status based on NCHS recode; ambiguous categories (“private/unknown if public” and “public/unknown if private”) coded as “private only” or “public only.”

dActivity limitation was assessed in 15 domains: bathing, dressing, eating, toileting, transferring, walking, getting outside, light housework, heavy housework, transportation, meal preparation, shopping for groceries, managing medications, managing money, and using the telephone.

Individuals who described their health as fair or poor were more likely to be noncompliant than were those who rated their health as good, very good, or excellent (OR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.7). The relationship between severity of disability and cost-associated noncompliance appeared to be curvilinear, with the highest level of noncompliance among moderately impaired adults who were limited in, but did not require assistance with, 1 or more activities of daily living (OR = 1.9; 95% CI = 1.5, 2.5). Disabled adults who were prescribed 3 or more medications were more likely than those who were prescribed 1 or 2 medications to report cost-associated noncompliance (3–5 medications: OR = 1.4; 95% CI = 1.1, 1.7; 6 or more medications: OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.2, 2.1).

Sex and race/ethnicity appeared to be only modestly related to cost-associated noncompliance, but there was a strong negative relationship between age and noncompliance: younger adults (those aged 18–34 years) were nearly 10 times more likely to be noncompliant as a result of cost than were members of the oldest cohort (those 75 years or older; OR = 0.1; 95% CI = 0.1, 0.2). However, members of younger cohorts were also less likely to be prescribed medications.

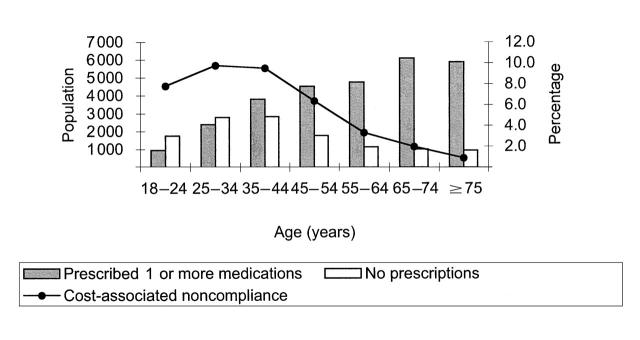

To clarify this relationship, we plotted the number of adults with prescriptions and the proportions reporting cost-associated noncompliance according to age group. Figure 1 ▶ shows that prescription rates increased with age: only 35% of disabled adults aged 18 to 24 years were prescribed medications, in comparison with 86% of adults aged 65 years or older. Among disabled adults with prescriptions, rates of cost-associated noncompliance peaked at about 10% for those aged 25 to 44 years and declined sharply in older age cohorts. Only about 2% of adults aged 65 to 74 years reported cost-associated noncompliance, and this rate dropped to below 1% among adults 75 years or older.

FIGURE 1.

—Number of disabled adults who had prescriptions and proportions noncompliant owing to cost, by age group.

All noncompliant respondents were asked whether they had experienced any adverse health consequences (Table 4 ▶). Among those who were noncompliant owing to cost, more than half identified 1 or more resulting health problems. The most common problems involved exacerbation of conditions or symptoms; for example, nearly 350 000 people reported pain or discomfort resulting from cost-associated noncompliance. A relatively small proportion of respondents reported that noncompliance problems led directly to additional health care use: an estimated 66 000 people had to visit a doctor's office or emergency room, and about 46 000 had to be hospitalized.

TABLE 4.

—Reported Health Problems Attributed to Medication Noncompliance due to Cost Among Adults With Disabilities

| Estimated No. (%) | |

| Experienced one or more problems owing to noncompliance | 672 (52.5) |

| Pain or discomfort | 349 (27.2) |

| Condition for which medicine prescribed got worse | 267 (20.9) |

| Dizziness or fainting | 159 (12.4) |

| Change in blood pressure, breathing, or other vital signs | 154 (12.0) |

| Disorientation | 93 (7.3) |

| Had to go to the doctor or emergency room | 66 (5.2) |

| Other condition(s) got worse | 64 (5.0) |

| Had to be admitted to the hospital | 46 (3.6) |

| Overdose or withdrawal | 37 (2.9) |

| Drug reaction | 35 (2.8) |

| Other | 152 (11.9) |

| Total noncompliant owing to cost | 1280 (100) |

Note. Data are population estimates in 1000s derived from the National Center for Health Statistics.29

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that about 1.3 million adults with disabilities reported that the cost of the medicine(s) they were prescribed was so high that they could not afford to fill or refill their prescriptions or to take their medication as prescribed. More than half of this group identified 1 or more potentially serious and costly health problems that they attributed to noncompliance. These prevalence figures are impressive; for several reasons, however, they probably underestimate the true scope of drug affordability problems among people with disabilities.

First, our data did not allow us to estimate the number of people who take their medications as prescribed but do so at great personal cost. For some people with disabilities or chronic illnesses, limited incomes force a monthly choice between medication and food.31 Second, although only recently released to the research community, the surveys we examined are somewhat dated. Drug costs have skyrocketed in the period since the data were collected,2 potentially threatening the health and economic security of many more adults with and without disabilities.6,32,33 Third, all compliance data were self-reported and thus subject to biases associated with such survey methods.34 Indeed, underreporting of noncompliance is such a widely recognized problem26 that many researchers use independent verification strategies such as pill counts35 and electronic monitoring.36

Despite these limitations, our analysis raises some provocative research and policy questions. As might be expected, income and insurance status were strong predictors of noncompliance due to cost. The magnitude of the insurance differences, however, was striking; after other risk factors had been controlled, disabled adults without insurance were nearly 4 times more likely than those with private insurance to report medication noncompliance due to cost.

The finding that people who were in poorer health or who took more medications were also at higher risk of cost-associated noncompliance was consistent with previous research. However, the curvilinear relationship found between severity of disability and noncompliance due to cost merits further investigation. The relatively lower rate of noncompliance among Hispanic adults with disabilities was unanticipated, and additional research is clearly needed to verify this relationship.

Our most remarkable finding from a public policy perspective was that cost-associated noncompliance was concentrated primarily in younger cohorts. This result seems to contradict much of the recent political commentary on drug affordability, although other studies have also revealed a negative relationship between age and compliance.21,22 Additional research is needed, however, before we would concur with the conclusion of Park et al. that, in terms of medication compliance, “older is wiser.”23

Indeed, at least for the population of adults with disabilities, the more appropriate adage might be “younger is poorer” (or, at least, “younger is less likely to be insured”). Most of the 1.3 million disabled adults identified in this study would not be helped by any of the current proposals to expand Medicare drug coverage, because only 27% received Medicare. If this population were included in the policy debate and ways were found to increase prescription drug coverage for all adults with chronic illnesses and disabilities, much of the exacerbation of symptoms and conditions found in this study—and many of the associated health care expenditures—could be avoided.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported in part by a fellowship from the National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research (grant H133F990001) and by a grant from the Mary Jane Neer Fund at the University of Illinois. The Disability Follow-Back Survey adult data were provided by the National Center for Health Statistics, and prevalence data on prescription drug use among adults with disabilities were first presented by John Hough (of the Division of Birth Defects, Child Development, Disability and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) at the 1999 Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association.

Note. The analyses, interpretations, and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Center for Health Statistics, the National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research, Washington State University, or the University of Illinois.

J. Kennedy designed the study, conducted the analyses, and wrote the article. C. Erb conducted the literature review, collaborated in analysis design and interpretation, and contributed to the writing of the article.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Long SH. Prescription drugs and the elderly: issues and options. Health Aff. 1994;13(2):157–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hard to Swallow: Rising Prices for America's Seniors. Washington, DC: Families USA; 1999.

- 3.Moran DW. Prescription drugs and managed care: can ‘free-market detente’ hold? Health Aff. 2000;19(2):63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClellan M, Spatz ID, Carney S. Designing a Medicare prescription drug benefit: issues, obstacles, and opportunities. Health Aff. 2000;19(2):26–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Disturbing Truths and Dangerous Trends: The Facts About Medicare Beneficiaries and Prescription Drug Coverage. Washington, DC: National Economic Council; 1999.

- 6.Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Inadequate prescription-drug coverage for Medicare enrollees—a call to action. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:722–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frogue J. How to Provide Prescription Drug Coverage Under Medicare. Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation; 1999.

- 8.Chrischilles EA, Foley DJ, Wallace RB, et al. Use of medications by persons 65 and over: data from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. J Gerontol. 1992;47:M137–M144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaPlante MP, Rice DP, Wenger BL. Medical Care Use, Health Insurance, and Disability in the United States. Washington, DC: National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research; 1995.

- 10.Max W, Rice DP, Trupin L. Medical Expenditures for People With Disabilities. Washington, DC: National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research; 1995.

- 11.Mueller C, Schur C, O'Connell J. Prescription drug spending: the impact of age and chronic disease status. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1626–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis M, Poisal J, Chulis G, Zarabozo C, Cooper B. Prescription drug coverage, utilization, and spending among Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff. 1999;18(1):231–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poisal JA, Murray LA, Chulis GS, Cooper BS. Prescription drug coverage and spending for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev. 1999;20(3):15–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuart B, Grana J. Ability to pay and the decision to medicate. Med Care. 1998;36:202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinberg EP, Gutierrez B, Momani A, Boscarino JA, Neuman P, Deverka P. Beyond survey data: a claims-based analysis of drug use and spending by the elderly. Health Aff. 2000;19(2):198–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sackett DL, Haynes RB, eds. Compliance With Therapeutic Regimens. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1976.

- 17.Costa FV. Compliance with antihypertensive treatment. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1996;18:463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olshaker JS, Barish RA, Naradzay JF, Jerrard DA, Safir E, Campbell L. Prescription noncompliance: contribution to emergency department visits and cost. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:909–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Col N, Fanale JE, Kronholm P. The role of medication noncompliance and adverse drug reactions in hospitalizations of the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:841–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maronde RF, Chan LS, Larsen FJ, Strandberg LR, Laventurier MF, Sullivan SR. Underutilization of antihypertensive drugs and associated hospitalization. Med Care. 1989;27:1159–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey JE, Lee MD, Somes GW, Graham RL. Risk factors for antihypertensive medication refill failure by patients under Medicaid managed care. Clin Ther. 1996;18:1252–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faulkner DL, Young C, Hutchins D, McCollam JS. Patient noncompliance with hormone replacement therapy: a nationwide estimate using a large prescription claims database. Menopause. 1998;5:226–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park DC, Hertzog C, Leventhal H, et al. Medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis patients: older is wiser. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Avorn J. Compliance with antihypertensive therapy among elderly Medicaid enrollees: the roles of age, gender, and race. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1805–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bazargan M, Barbre AR, Hamm V. Failure to have prescriptions filled among black elderly. J Aging Health. 1993;5:264–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McElnay JC, McCallion CR, al-Deagi F, Scott M. Self-reported medication non-compliance in the elderly. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;53:171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Botelho RJ, Dudrak RD. Home assessment of adherence to long-term medication in the elderly. J Fam Pract. 1992;35:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massey JT, Moore TF, Parsons VL, Tadros W. Design and estimation for the National Health Survey, 1985–94. Vital Health Stat 2. 1989;No. 110.

- 29.Data File Documentation, National Health Interview Survey on Disability, Phase 1 and Phase 2, 1994. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1998. CD-ROM series 10, No. 9.

- 30.Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data (SUDAAN), Version 7.5. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1998.

- 31.Chubon SJ, Schulz RM, Lingle EW Jr, Coster-Schulz MA. Too many medications, too little money: how do patients cope? Public Health Nurs. 1994;11:412–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thornton D. By the numbers: the rising costs of prescription drugs. Healthplan. 1999;40(5):71–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogowski J, Lillard LA, Kington R. The financial burden of prescription drug use among elderly persons. Gerontologist. 1997;37:475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Babbie E, Wagenaar T. Practicing Social Research. 3rd ed. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth Publishing Co; 1983.

- 35.Larrat EP, Taubman AH, Willey C. Compliance-related problems in the ambulatory population. Am Pharmacy. 1990;30(2):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park DC, Morrell RW, Frieske D, Kincaid D. Medication adherence behaviors in older adults: effects of external cognitive supports. Psychol Aging. 1992;7:252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]