Abstract

Objectives. This study examined the justice of decision-making procedures and interpersonal relations as a psychosocial predictor of health.

Methods. Regression analyses were used to examine the relationship between levels of perceived justice and self-rated health, minor psychiatric disorders, and recorded absences due to sickness in a cohort of 506 male and 3570 female hospital employees aged 19 to 63 years.

Results. The odds ratios of poor self-rated health and minor psychiatric disorders associated with low vs high levels of perceived justice ranged from 1.7 to 2.4. The rates of absence due to sickness among those perceiving low justice were 1.2 to 1.9 times higher than among those perceiving high justice. These associations remained significant after adjustment for behavioral risks, workload, job control, and social support.

Conclusions. Low organizational justice is a risk to the health of employees.

In today' rapidly changing work life, organizational justice may become increasingly important to employees.1,2 Justice includes a procedural component (the extent to which decision-making procedures include input from affected parties, are consistently applied, suppress bias, and are accurate, correctable, and ethical) and a relational component (polite, considerate, and fair treatment of individuals).3,4 Prior research shows that perceived justice is associated with people' feelings and behaviors in social interactions,5–8 but its effects on health are unknown. We therefore examined the contribution of procedural and relational justice to employee health.

METHODS

Study Sample

We used employers' records to identify all 5342 hospital employees (880 men and 4462 women) in the service of the 7 hospitals in 1 of the 23 health care districts in Finland in the beginning of 1998. Altogether, 4076 employees (76%; 506 men and 3570 women) responded to a questionnaire on justice and other variables. The mean age of the respondents was 42.6 years (range = 19–63); 7% were doctors (162 men and 142 women), 50% nurses (124 men and 1914 women), 14% x-ray and laboratory staff (21 men and 532 women), 12% administrative staff (49 men and 436 women), and 17% maintenance, cleaning, and other staff (150 men and 546 women).

Measures

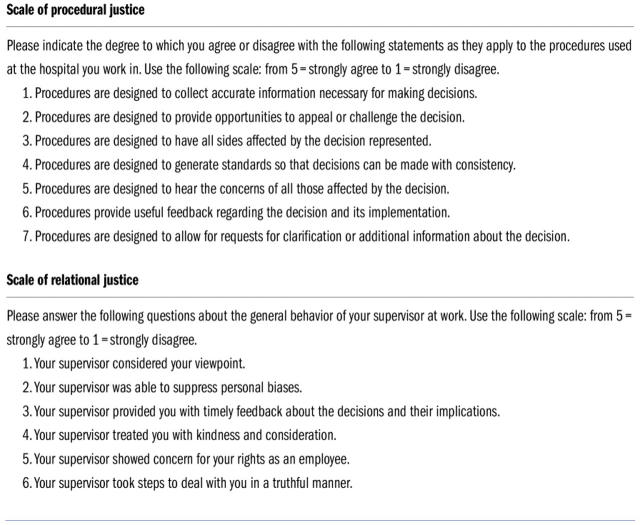

Scales of procedural justice (7 items; range of scale = 1–5; mean score of responses = 2.8; SD = 0.7; α = .90) and relational justice (6 items; range of scale = 1–5; mean score of responses = 3.5; SD = 0.9; α = .81) were adopted from Moorman7 (Figure 1 ▶). Both scales have been associated with organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and retaliation,6,8,9 and they were moderately interrelated (r = 0.30).

FIGURE 1.

—Scales used to rate levels of perceived organizational justice.

The outcome variables were self-rated health, minor psychiatric morbidity, and recorded absence due to sickness (sickness absence). Poor health was indicated by health ratings less than good (n = 766).10–12 Minor psychiatric morbidity was assessed with the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (α = .80); cases were those that scored 4 or higher on the questionnaire (n = 920).13–15 Self-certified and medically certified sick leaves in 1997 and 1998 were obtained from employers' registers. Self-certified sickness absences were 3 days or less, while medically certified absences, for which a physician' examination and a medical certificate were always required, were more than 3 days.16–18

We measured covariates by using the following standard criteria: age, sex, income, smoking status (never smoker, n = 2797; former smoker, n = 557; current smoker, n = 582), alcohol consumption19 (low consumption: 40 g or less of pure alcohol per week, n = 3090; high consumption: more than 280 g for men and more than 190 g for women, n = 396), sedentary lifestyle (less than half an hour of fast walking per week; n = 2135),20 and body mass index (<25 kg/m2, n = 3813; 25–30 kg/m2, n = 1179; >30 kg/m2, n = 350). Psychosocial factors were workload21,22 (4 items; range = 1–5; mean = 3.5; SD = 0.9; α = .85), job control23 (9 items; range = 1–5; mean = 3.6; SD = 0.7; α = .84), and social support24 (6 items; range = 0–30; mean = 12.0; SD = 5.3; α = .79).

Statistical Analysis

Justice and other psychosocial measures were divided into quartiles and treated as categorical variables. Associations of justice variables with self-rated health and minor psychiatric morbidity, determined by logistic regression analysis, were expressed as odds ratios. We studied associations of justice variables with sickness absences by using Poisson regression and rate ratios. Ninety-five-percent confidence intervals were calculated and adjustments were made for demographics, behavioral risks, and established psychosocial factors.

RESULTS

There were no differences between age groups or sexes in the evaluation of procedural justice (for men, mean = 3.62, SD = 0.93; for women, mean = 3.60, SD = 0.95) or relational justice (for men, mean = 2.7, SD = 0.82; for women, mean = 2.79, SD = 0.72), but employees with high income perceived significantly lower levels of procedural justice than other employees (χ23 = 46.10; P < .001).

Among men, low procedural justice was associated with a 2-fold risk of poor self-rated health and an almost 4-fold risk of minor psychiatric disorders, but the associations were not significant after adjustment for other psychosocial factors. Among women, associations between procedural justice, self-rated health, and minor psychiatric disorders were significant irrespective of adjustments (Table 1 ▶).

TABLE 1.

—Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) of Poor Self-Rated Health and Minor Psychiatric Disorders, by Level of Organizational Justice

| Poor Self-Rated Health, OR (95% CI) | Minor Psychiatric Disorders, OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Adjusted for Demographicsa | Adjusted for Demographics and Behavioral Risksb | Adjusted for Demographics, Behavioral Risks, and Other Psychosocial Factors c | Adjusted for Demographicsa | Adjusted for Demographics and Behavioral Risksb | Adjusted for Demographics, Behavioral Risks, and Other Psychosocial Factors c | |

| Men | ||||||

| Procedural justice | ||||||

| 1 (high) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1.62 (0.75, 3.47) | 1.61 (0.72, 3.63) | 1.21 (0.48, 3.07) | 2.27 (1.01, 5.12) | 2.55 (1.09, 5.99) | 2.35 (0.92, 6.01) |

| 3 | 1.75 (0.75, 3.49) | 1.81 (0.88, 3.74) | 1.39 (0.60, 3.19) | 2.50 (1.18, 5.29) | 2.38 (1.09, 5.21) | 1.66 (0.69, 3.99) |

| 4 (low) | 2.35 (1.18, 4.66) | 2.07 (1.00, 4.28) | 1.84 (0.81, 3.19) | 4.20 (2.04, 8.67) | 3.73 (1.74, 8.00) | 2.28 (0.96, 5.42) |

| Relational justice | ||||||

| 1 (high) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0.69 (0.33, 1.44) | 0.64 (0.29, 1.39) | 0.66 (0.28, 1.53) | 1.16 (0.55, 2.44) | 1.30 (0.59, 2.89) | 0.90 (0.38, 2.09) |

| 3 | 1.15 (0.55, 2.42) | 1.01 (0.45, 2.25) | 1.00 (0.40, 3.19) | 1.59 (0.74, 3.43) | 1.69 (0.73, 3.89) | 1.03 (0.42, 2.56) |

| 4 (low) | 1.80 (0.85, 3.82) | 1.43 (0.63, 3.18) | 1.30 (0.53, 3.19) | 2.38 (1.10, 5.14) | 2.46 (1.07, 5.69) | 1.40 (0.56, 3.46) |

| Women | ||||||

| Procedural justice | ||||||

| 1 (high) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1.54 (1.20, 1.99) | 1.69 (1.30, 2.21) | 1.76 (1.32, 2.35) | 1.40 (1.11, 1.78) | 1.41 (1.11, 1.81) | 1.32 (1.01, 1.73) |

| 3 | 1.51 (1.17, 1.95) | 1.63 (1.25, 2.15) | 1.56 (1.16, 2.08) | 1.96 (1.55, 2.47) | 1.94 (1.53, 2.46) | 1.84 (1.42, 2.39) |

| 4 (low) | 1.70 (1.29, 2.75) | 1.79 (1.35, 2.37) | 1.55 (1.13, 2.12) | 2.33 (1.83, 2.97) | 2.26 (1.76, 2.89) | 1.89 (1.44, 2.49) |

| Relational justice | ||||||

| 1 (high) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1.21 (0.93, 1.57) | 1.23 (0.94, 1.62) | 1.09 (0.83, 1.46) | 0.99 (0.79, 1.26) | 1.03 (0.81, 1.38) | 0.97 (0.75, 1.26) |

| 3 | 1.37 (1.03, 1.80) | 1.40 (1.05, 1.85) | 1.18 (0.87, 1.59) | 1.45 (1.15, 1.86) | 1.49 (1.15, 1.91) | 1.30 (1.01, 1.70) |

| 4 (low) | 1.74 (1.33, 2.27) | 1.66 (1.26, 2.22) | 1.24 (0.92, 1.68) | 2.05 (1.61, 2.60) | 2.10 (1.64, 2.68) | 1.65 (1.27, 2.15) |

aAge and income.

bSmoking, alcohol consumption and sedentary lifestyle, and body mass index.

cWorkload, job control, and social support.

Low relational justice was associated with about a 2-fold risk of poor self-rated health and minor psychiatric disorders, although in the fully adjusted models only the association with minor psychiatric disorders among women remained significant (Table 1 ▶).

Procedural justice and relational justice were significantly associated with selfcertified and medically certified sickness absence. The association of relational justice with medically certified sickness absence was significantly stronger among men than among women (P < .01). There were no interactions between sex and procedural justice (Table 2 ▶).

TABLE 2.

—Rate Ratios (RRs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) of Sickness Absence, by Level of Procedural and Relational Justice

| Self-Certified Sickness Absence, RR (95% CI) | Medically Certified Sickness Absence, RR (95% CI) | |||||

| Adjusted for Demographicsa | Adjusted for Demographics and Behavioral Risksb | Adjusted for Demographics, Behavioral Risks, and Other Psychosocial Factorsc | Adjusted for Demographicsa | Adjusted for Demographics and Behavioral Risksb | Adjusted for Demographics, Behavioral Risks, and Other Psychosocial Factorsc | |

| Men | ||||||

| Procedural justice | ||||||

| 1 (high) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1.40 (1.21, 1.77) | 1.44 (1.14, 1.82) | 1.75 (1.35, 2.27) | 1.48 (1.06, 2.07) | 1.60 (1.14, 2.23) | 1.61 (1.12, 2.32) |

| 3 | 1.31 (1.05, 1.62) | 1.19 (0.95, 1.49) | 1.46 (1.13, 1.87) | 1.31 (0.99, 1.78) | 1.35 (0.99, 1.85) | 1.29 (0.90, 1.83) |

| 4 (low) | 1.19 (0.96, 1.48) | 1.15 (0.93, 1.44) | 1.40 (1.08, 1.81) | 1.25 (0.92, 1.71) | 1.26 (0.91, 1.73) | 1.36 (0.95, 1.94) |

| Relational justice | ||||||

| 1 (high) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1.09 (0.87, 1.37) | 1.13 (0.89, 1.44) | 1.37 (0.91, 1.51) | 0.92 (0.66, 1.29) | 0.88 (0.62, 1.24) | 0.95 (0.66, 1.38) |

| 3 | 1.45 (1.15, 1.82) | 1.42 (1.12, 1.81) | 1.43 (1.10, 1.87) | 1.09 (0.78, 1.55) | 1.07 (0.75, 1.52) | 1.25 (0.85, 1.83) |

| 4 (low) | 1.91 (1.51, 2.41) | 1.91 (1.50, 2.43) | 1.92 (1.46, 2.51) | 1.82 (1.31, 2.53) | 1.68 (1.20, 2.35) | 1.83 (1.27, 2.65) |

| Women | ||||||

| Procedural justice | ||||||

| 1 (high) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1.20 (1.13, 1.28) | 1.21 (1.13, 1.28) | 1.20 (1.12, 1.29) | 1.17 (1.07, 1.28) | 1.19 (1.09, 1.31) | 1.19 (1.08, 1.32) |

| 3 | 1.28 (1.20, 1.36) | 1.28 (1.20, 1.36) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.33) | 1.19 (1.09, 1.30) | 1.21 (1.11, 1.33) | 1.20 (1.09, 1.33) |

| 4 (low) | 1.31 (1.24, 1.40) | 1.32 (1.24, 1.41) | 1.27 (1.18, 1.36) | 1.51 (1.38, 1.65) | 1.52 (1.39, 1.67) | 1.44 (1.30, 1.59) |

| Relational justice | ||||||

| 1 (high) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.02) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.03) | 0.94 (0.88, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.85, 1.02) | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) | 0.91 (0.83, 1.01) |

| 3 | 1.11 (1.05, 1.19) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) | 1.07 (1.00, 1.14) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.16) | 1.05 (0.95, 1.16) | 1.01 (0.91, 1.11) |

| 4 (low) | 1.20 (1.12, 1.28) | 1.15 (1.09, 1.24) | 1.07 (1.00, 1.14) | 1.38 (1.26, 1.51) | 1.30 (1.18, 1.42) | 1.18 (1.08, 1.31) |

aAge and income.

bSmoking, alcohol consumption and sedentary lifestyle, and body mass index.

cWorkload, job control, and social support.

DISCUSSION

Organizational justice was associated with health among both men and women across most of the health outcomes studied; this was true not only for those in the medical professions but also for those with administrative and maintenance jobs, after adjustment for other psychosocial factors.

Relational justice was a stronger predictor of sickness absence for men than for women. This difference, however, might reflect not only a difference between the sexes but also the fact that hospital occupations are gender related. For example, over 50% of the physicians were men, whereas over 93% of the nurses were women. Organizational justice may have different meanings for members of highly ranked occupations related to management than for shop-floor employees.25 The size differences between the male and female samples may also have affected the detected differences in significance between sexes.

Our results may shed light on the effects of other psychosocial models of organizational behavior. Hemingway and Marmot2 concluded that only about half of the studies they reviewed supported the role of workload and job control or social support in predicting coronary heart disease. Although organizational justice partly overlaps with these psychosocial factors, it also seems to tap additive elements associated with employee health18,26,27—for example, organizational consistency, accuracy, ethicality, managerial decision making, procedures used, and discrimination in organizations.28–30

The model of effort–reward imbalance31 suggests that high effort spent at work combined with low reward in terms of salary, esteem, or job security defines a state of distress that increases health problems. Our findings on procedural justice show that people seem to be affected not only by rewards as such but also by the procedures used to determine how they will be distributed.

Replications with prospective data and with other kinds of organizations and occupational groups are still needed to assess the causality and generalizability of the association between organizational justice and employee health.

Acknowledgments

This study project was supported by the Finnish Work Environment Fund (FWEF) (project no. 97316) and the participating hospitals. M. Elovainio' work is supported by the FWEF (project no. 96052), and M. Kivimäki' work is supported by the Academy of Finland (project no. 44968).

M. Elovainio, who was the principal author, designed the hypotheses, and conducted the data analysis, is the guarantor for the paper. M. Kivimäki, the coprincipal investigator, coordinated the project, designed and collated the data, helped in the data analysis, and contributed to the writing. J. Vahtera helped in the data analysis and advised in the interpretation and presentation of the results.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Hurrell JJ Jr. Are you certain? Uncertainty, health, and safety in contemporary work. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1012–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemingway H, Marmot M. Psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease: systematic review of a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 1999;318:1460–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bies RJ, Moag JS. Interactional justice: communication criteria of fairness. In: Lewicki RJ, Sheppard BH, Bazerman MZ, eds. Research on Negotiations in Organizations. Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press; 1986:43–55.

- 4.Kramer RM, Tyler TR. Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research. London, England: Sage; 1996.

- 5.Shapiro DL, Brett JM. Comparing three processes underlying judgements of procedural justice: a field study of mediation and arbitration. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:1167–1177. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg J. Organizational justice: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. J Manage. 1990;16:399–432. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moorman RH. Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? J Appl Psychol. 1991;76:845–855. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elovainio M, Kivimäki M, Helkama K. Organizational justice evaluations, job control and occupational strain. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86:418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scarlicki DP, Folger R. Retaliation in the workplace: the roles of distributive, procedural and interactional justice. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82:434–443. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Idler EL, Angel RJ. Self-rated health and mortality in the NHANES-I epidemiological follow-up study. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:446–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991;337:1387–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, Pasanen M, Urponen H. Self-rated health as a health measure: the predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:517–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg D. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. London, England: Oxford University Press; 1972.

- 14.Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, Puccinelli M, Gureje O, Rutter C. The validity of the two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med. 1997;27:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg D, Williams P. A User' Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Berkshire, United Kingdom: NFER–Nelson Publishing Co; 1988.

- 16.Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, Thomson L, Griffiths A, Cox T, Pentti J. Psychosocial factors predicting employee sickness absence during economic decline. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82:858–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vahtera J, Kivimäki M, Pentti J. Effect of organizational downsizing on health of employees. Lancet. 1997;350:1124–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, Pentti J, Ferrie JE. Factors underlying the effect of organisational downsizing on health of employees: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320:971–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Langinvainio H, Romanov K, Sarna S, Rose RJ. Genetic influences on use and abuse of alcohol: a study of 5638 adult Finnish twin brothers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1987;11:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kujala UM, Kaprio J, Sarna S, Koskenvuo M. Relationship of leisure-time physical activity and mortality. JAMA. 1998;279:440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PE. The Nurse Stress Index. Work Stress. 1989;3:335–345. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper CL, Mitchell S. Nurses under stress: a reliability and validity study of the NSI. Stress Med. 1990;6:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karasek RA. Job Content Questionnaire and User' Guide, Revision 1.1. Los Angeles: University of Southern California; 1985.

- 24.Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR. A brief measure of social support: practical and theoretical implications. J Soc Personal Relationships. 1987;4:497–510. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan GA. People and places: contrasting perspectives on the association between social class and health. Int J Health Serv. 1996;26:507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosma H, Marmot MG, Hemingway H, Nicholson AC, Brunner E, Stansfeld SA. Low job control and risk of coronary heart disease in the Whitehall II (prospective cohort) study. BMJ. 1997;314:558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson JV, Stewart W, Hall EM, Fredlund P, Theorell T. Long-term psychosocial work environment and cardiovascular mortality among Swedish men. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Firth-Cozens J. Sources of stress in women junior house officers. BMJ. 1990;301:89–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;9:70–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieger N. Embodying inequity: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv. 1999;29:19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1:27–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]