Abstract

Licensed hairdressing facilities are prevalent in communities nationwide and represent a unique and promising channel for delivering public health interventions. The Rhode Island Smokefree Shop Initiative tested the feasibility of using these facilities to deliver smoking policy interventions statewide. A statewide survey of hairdressing facilities was followed by interventions targeted to the readiness level (high/low) of respondents to adopt smoke-free policies.

THE RHODE ISLAND SMOKEfree Shop Initiative (SSI) involved a 2-phase effort. First, a questionnaire was mailed to 1319 licensed hairdressing facilities to determine their smoking policies; 349 facilities responded. Among respondents, 44% (n = 152 349) reported having a total smoking ban already in place. Multiple logistic regression analyses revealed that responding facility owners who were current smokers were 16% less likely to work in a shop with a restrictive smoking policy (odds ratio [OR] = .16; 95% confidence interval [CI] = .06, .44), and respondents who believed that environmental tobacco smoke harms health were 88% more likely to work in a shop with a restrictive smoking policy (OR = 1.88; 95% CI = 1.11, 3.20).

To build the smokefree shop policy initiative, responses to 1 item on the mailed questionnaire were used to categorize the respondent's readiness to offer a more restrictive smoking policy. Thirty-eight percent of respondents without a total ban already in place (75/197) were not interested in adopting a more restrictive smoking ban and were categorized as having “low” readiness; 62% of respondents (122/197) were interested in or thinking about adopting a more restrictive smoking policy and were categorized as having “high” readiness.

In the project's second phase, a smoking policy intervention was developed and tailored to shop owner self-reported readiness level (high or low) and then delivered by trained professionals according to a tested protocol. A Smokefree Shop Initiative advisory board was recruited and organized during the planning phase to help the research team understand how to work best with beauty industry representatives. Advisory board members included shop owners, hairstylists, distributors of hair products, instructors from the local beauty schools, the president of the statewide professional trade association, and consumers. Together, board members reviewed all program plans, questionnaire results, and intervention materials. Articles were placed in a quarterly trade newsletter describing the initiative's aims, resources, and upcoming events. Advisory board members were invaluable spokespersons for the initiative and offered guidance and support for all aspects of the program. Selected hairdressing facility owners from Massachusetts pretested the intervention materials before implementation in Rhode Island.

The intervention was tailored to the level of owner readiness to adopt a more restrictive smoking policy. Facility respondents who reported that a total smoking ban was already in place at baseline received a congratulatory letter, a framed certificate, and free mirror stickers promoting their smoke-free status. Low-readiness facilities received a personalized cover letter, printed facts about the negative effects of smoke on beauty and health, a description of the initiative, and information about resources available if they became interested in going smoke-free at some future time. High-readiness facilities were sent all of the same materials as those with low interest and received a phone call offering a free on-site consultation with a trained member of the research team about how to go smoke-free. All high-readiness facilities also received the Smokefree Policy Guide.

RESULTS

At 12 months postintervention, follow-up phone calls were made to a randomly selected sample of high-readiness (n = 38) and low-readiness (n = 43) sites that were exposed to the intervention. Seventy-seven percent of low-interest sites (33/43) and 61% of highinterest sites (23/38) completed the follow-up phone surveys. Among the responding high-readiness facilities contacted at the 12-month follow-up, 22% reported making a change to a more restrictive policy within the preceding 12 months. Forty-eight percent of these respondents reported adopting a total smoking ban. When respondents were asked about the primary motivation for adopting these changes, the personal health of the respondent was cited most frequently, followed by employee health and customer or employee satisfaction.

Among the low-readiness sites at the 12-month follow-up, 12% reported that their smoking policy had changed in the preceding 12 months. Thirty percent of those respondents were either taking action to make their policy more restrictive or had already developed a total ban on smoking. Among those who did not change to a more restrictive policy and were not interested in doing so, 56% cited concern about losing customers as the main reason for not implementing a more restrictive policy at the 12-month follow-up.

KEY FINDINGS

Hairdressing facility owners were interested in the link between beauty, health, and smoking.

Facility owners who were offered a minimal intensity, readiness-matched policy intervention were willing to consider adopting a more restrictive smoking policy.

Facility owners were more likely to have a restrictive policy if the owner was a nonsmoker and believed that environmental tobacco smoke harms health.

DISCUSSION

Several novel intervention efforts have used hairdressing facilities to address issues of hypertension, alcohol use, condom use, and breast and prostate cancer screening.1–8 This study represents the first effort to evaluate the feasibility of using hairdressing facilities to address smoke-free policies at work. Addressing the issue of smoke in the workplace can be sensitive, but results from the statewide questionnaire demonstrated reasonable interest among hairdressing facility owners in going smoke-free. Respondents who were exposed to the intervention also demonstrated improved knowledge about the health and beauty risks of smoking and secondhand smoke.

In this feasibility study, respondents were more likely to be interested in health-related issues than were nonrespondents, which may limit the generalizability of the study findings. Given the vast number of licensed hairdressing facilities in any given community, region, or state, however, reaching owners who report some degree of readiness to go smoke-free and moving them into action probably will create health benefits for the public and for employees who work in these facilities. In fact, with a very minimal intervention, we achieved some success in convincing facilities to adopt a smoke-free policy over a 12-month period.

Rhode Island Project ASSIST invested approximately $32 000 in the Smokefree Shop Initiative over 2 years—a fairly small sum in relation to the large public health impact of smoke exposure among owners, their employees, and members of the public who frequent hairdressing facilities on a regular basis. Interventions in hairdressing facilities offer the possibility of reach and reinforcement of tobacco control messages, as well as a wide range of other health messages that link beauty and health.

NEXT STEPS

Raising awareness about the health risks of secondhand smoke among hairdressing facility owners, employees, and customers may motivate customers and employees to advocate for smoke-free workplaces and public places. Interventions that capitalize on the unique relationship between stylist and customer are promising avenues for engaging interested hairstylists to deliver brief motivational interventions that address health behaviors with links to beauty (e.g., sun exposure, physical activity, diet). Hairdressing facilities also remain an important channel for recruiting women into other health-related programs or studies. We intend to explore these issues in our ongoing research, in partnership with licensed cosmetologists and community leaders.

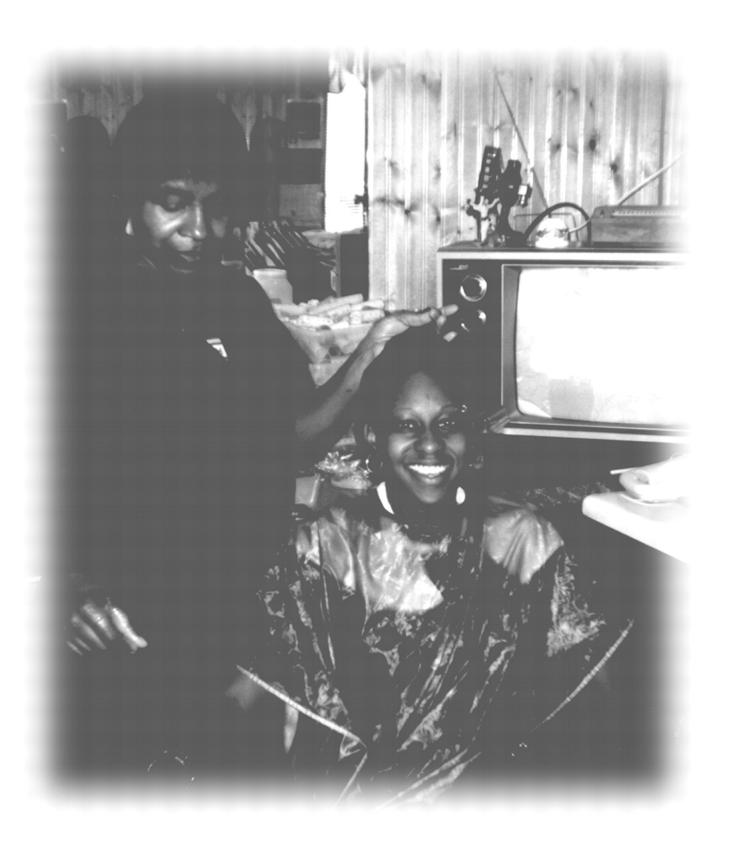

Figure .

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Rhode Island Project ASSIST, especially the late Dr. Judith Miller; partners from the Rhode Island hair salon industry and the Smokefree Shop Initiative Advisory Board; intervention staff (Mary Lynne Hixson, Suzanne Moriarty, Sheila Jacobs); data manager Mary Roberts; and Annice Kim for helpful edits on the final version of the manuscript.

L. A. Linnan was the principal investigator for the study, led the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. K. M. Emmons and D. B. Abrams consulted on all aspects of the project and edited several versions of the manuscript.

Resource

SSI Smokefree Policy Guide, a manual adapted from the Liberty Mutual Smoking Policy Guide developed by researchers at the Dana–Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Mass.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Delgado M. Alcoholism services and community settings: Latina beauty parlors as case examples. Alcoholism Treatment Q. 1998;16:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinrich SP, Boyd MD, Bradford D, Mossa MS, Weinrich M. Recruitment of African Americans into prostate cancer screening. Cancer Pract. 1998;6: 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kong BW. Community-based hypertension control programs that work. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1997;8: 409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green-Bishop JE. Condom machines going into hair salons. Baltimore Business Journal. April 8, 1996:12.

- 5.Key SW, Marble M. Trip to beauty parlor means more than haircut. Cancer Weekly Plus. October 28, 1996:7.

- 6.Sadler GR, Thomas AG, Dhanjal SK, Gebrekristos B, Wright F. Breast cancer screening adherence in African American women: Black cosmetologists promoting health. Cancer Supplement. 1998;3:1836–1839. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howze EH, Broyden RR, Impara JC. Using informal caregivers to communicate with women about mammography. Health Communication. 1992;4: 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forte DA. Community-based breast cancer intervention program for older African American women in beauty salons. Public Health Rep. 1995;110:179– 183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]