Abstract

Objectives. This study examined changes in tobacco promotions in the alternative press in San Francisco and Philadelphia from 1994 to 1999.

Methods. A random sample of alternative newspapers was analyzed, and a content analysis was conducted.

Results. Between 1994 and 1999, numbers of tobacco advertisements increased from 8 to 337 in San Francisco and from 8 to 351 in Philadelphia. Product advertisements represented only 45% to 50% of the total; the remaining advertisements were entertainment-focused promotions, mostly bar–club and event promotions.

Conclusions. The tobacco industry has increased its use of bars and clubs as promotional venues and has used the alternative press to reach the young adults who frequent these establishments. This increased targeting of young adults may be associated with an increase in smoking among this group.

During the 1990s, bars and nightclubs became major promotional venues for the tobacco industry. Inside bars, patrons are exposed to a variety of advertisements, promotional items, and events, including logos on cocktail napkins, sale of cigarettes behind the bar, and sponsorship of live music events.1–7 These venues offer an agerestricted, young adult–focused environment where substance use (tobacco and alcohol) is legal and socially reinforced. Age restriction allows these promotional activities to continue with minimal criticism or surveillance from public health or tobacco control advocates because of public health's emphasis on smoking initiation among adolescents.8,9 This focus on adolescents ignores the fact that smoking initiation occurs over several periods, including young adulthood (the ages of 18 to 24 years).10–13

Young adulthood is an important time in the solidification of smoking patterns, because it is usually a period of transition from experimental smoking to nicotine addiction.11–13 Smoking patterns, including initiation, in young adults have not been static and are amenable to the influence of tobacco marketing. Indeed, smoking in this group has been increasing,14–16 with first-use rates approaching 8.6% in the mid-1990s.17

To quantify the changing role of tobacco product bar promotions, we examined the number and nature of tobacco industry–sponsored bar promotions advertised in the alternative press, which is heavily read by young adults.18–27 At the same time that the tobacco industry was increasing the use of bars as promotional venues, California implemented a law that required bars to be smoke free.28–30 To determine whether the presence of this law affected industry attempts to use bars as promotional venues, we compared bar-based tobacco promotions occurring in a city covered by the law (San Francisco) with those occurring in a similar city outside California where there were no restrictions on smoking in bars (Philadelphia). These 2 metropolitan areas have similar populations as well as similar percentages of young adults (ages 18–24 years) in their populations (8.6% in San Francisco and 8.4% in Philadelphia).

METHODS

We selected a random sample of 15 issues per year for the same weeks from each of 2 prominent alternative weekly newspapers, the San Francisco Bay Guardian and the Philadelphia City Paper, between January 1994 and December 1999. The samples were obtained from the San Francisco and Philadelphia public libraries or from street corner newspaper racks.

All print advertisements were coded for general characteristics, including size, placement in the publication, and brand of cigarette, and then classified into one of 5 specific categories: bar promotion, event promotion, product advertisement, paraphernalia, or antismoking advertisement (Table 1 ▶ describes these categories). The first author coded all of the samples.

TABLE 1.

—Descriptive Criteria for Classification of Tobacco Advertisements in the Alternative Press: San Francisco and Philadelphia, 1994–1999

| Type | Description–Criteria |

| Bar–club promotion | A small directory of local bars–clubs that contains a prominent cigarette logo and graphics |

| Event promotion | An event as the main focus of the advertisement; it contains the name, location, and description of the event; in most cases, the event is entertainment oriented |

| Product advertisement | Use of a combination of imagery and themes to create an advertisement for a particular cigarette brand without any mention of a bar–club or event |

| Paraphernalia | Miscellaneous items not printed in the pages of the publication but inserted loosely in the pages of an issue; examples include cocktail napkins, surveys for mailing lists |

| Antismoking advertisement | Use of different themes to educate the public regarding the dangers of smoking; the advertisements recorded were placed by public health advocates with support from the state of California |

Because random sampling resulted in an uneven distribution of samples from different quarters of each year, the individual samples were weighted by 13 (the number of weeks in a quarter), and divided by the number of issues in the sample in each quarter, and weighted frequencies (per quarter) were tabulated via the SPSS 8.0 and 9.0 frequencies and cross-tabulation functions (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). Chi-square analyses were used in comparisons between the 2 cities.

RESULTS

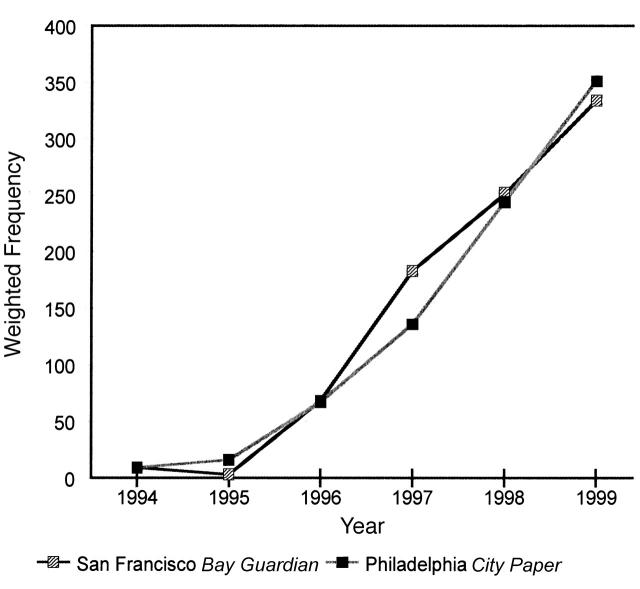

The frequency of advertisements, regardless of category, increased dramatically over the 5-year period we studied (Figure 1 ▶). In 1994, the San Francisco Bay Guardian contained only 8 advertisements. By 1999, this number had increased to 337. The Philadelphia City Paper showed a similar trend, with 8 advertisements in 1994 and 351 advertisements in 1999. Increases were seen across all 5 categories of analysis. The patterns of increase between the cities over the 5-year period were significantly different when cross tabulated with respect to year and publication (P = .007). The most notable difference occurred in 1997, when tobacco promotions in the San Francisco Bay Guardian exceeded those in the Philadelphia City Paper.

FIGURE 1.

—Changes in total advertisements over time: a comparison of the weighted frequencies of all tobacco advertisements recorded in a sample of the San Francisco Bay Guardian and the Philadelphia City Paper, 1994–1999.

The placement of advertisements also changed over time. In 1994 and 1995, no placement in entertainment sections was recorded. Beginning in 1996, the majority of advertisements were placed in the entertainment sections. In 1999, for example, advertisements in the San Francisco Bay Guardian were placed in entertainment sections 70% of the time; the corresponding rate for the Philadelphia City Paper was 65%.

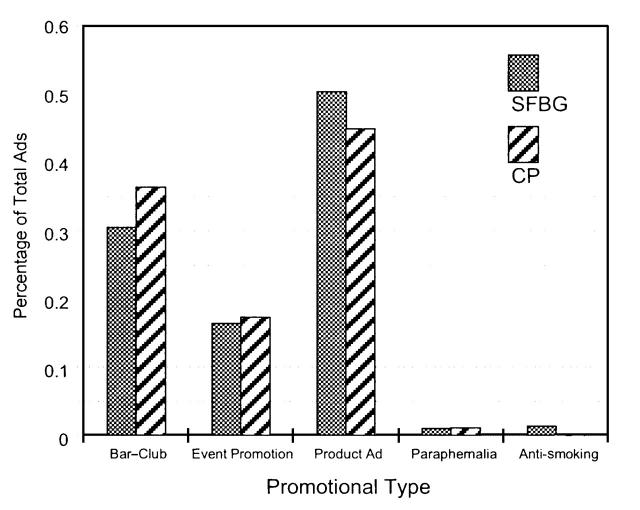

Figure 2 ▶ summarizes the proportions of advertisement types in each publication. Product advertisements were most frequent, but such advertisements represented only 50% of the total advertisements in the San Francisco Bay Guardian and 45% of the total advertisements in the Philadelphia City Paper. The remaining percentage of advertisements promoted sponsorship of bars or entertainment events.

FIGURE 2.

—Summary of promotional types as a percentage of total advertisements: San Francisco Bay Guardian (SFBG) and Philadelphia City Paper (CP), 1994–1999.

Bar and club promotions constituted 31% of the total advertisements analyzed in the San Francisco Bay Guardian and 36% of the total advertisements analyzed in the Philadelphia City Paper (Figure 2 ▶). Bar–club promotions began to appear in 1996 in both publications, with similar characteristics over time (P = .766). After their first appearance, bar–club promotions increased at a rate similar to that for total number of advertisements, averaging between 30% and 40% of the total from late 1996 through 1999. Bar–club promotions were more likely than any other advertisement to be placed in entertainment sections of the publications. More than 80% of bar–club promotions were placed in entertainment sections in both publications (86% in the San Francisco Bay Guardian and 80% in the Philadelphia City Paper).

Event promotions represented 17% of the total advertisements analyzed. Promotional events were subcategorized on the basis of type of event, the venue where it took place, and the presence of corporate citizenship. The most popular events were live music performances, which represented 68% of total promotional events in the San Francisco Bay Guardian and 65% in the Philadelphia City Paper; the remaining events were mostly sponsored parties. While most of these events occurred in bars or nightclubs (55% in San Francisco and 73% in Philadelphia), events were held in other venues as well, including arenas and resorts.

Tobacco companies often used event promotions to improve their corporate image. In many cases, this meant that a charitable donation would be made from the proceeds of the promotional event. Sixteen percent of the events in San Francisco and 23% in Philadelphia promoted a positive corporate image via charitable donations.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that the tobacco industry is increasing its use of bar and club venues in tobacco promotions aimed at young adults. This new strategy involves the use of entertainment to enhance industry promotions. The industry is using the alternative press, a medium that not only involves a heavy entertainment focus but also depends on young adults as a significant portion of its audience.18–27 Entertainment has been stressed in every detail of this new strategy. New types of advertisements have emerged that focus on entertainment venues (e.g., bars and clubs) or entertainment events (e.g., live music and sponsored parties). These advertisements are placed in parts of the publication that have the highest focus on entertainment, thereby increasing their visibility among young adult readers.

The tobacco industry appears to be successful in reaching this target audience of young adults aged 18 to 24 years. Members of this age group continue to be vulnerable to marketing of tobacco, because many of them are in the later stages of smoking initiation and, as a result, are still in the process of solidifying their addiction to tobacco.11,12 Young adults are not immune to “late” initiation of smoking (i.e., smoking their first cigarettes after the age of 18 years or 21 years). In the past, and among different ethnic groups, first use has been shown to occur after adolescence.31–39 Directed marketing toward young adults in social settings such as bars and nightclubs may raise the age at initiation toward what it was in the past. Current increases in young adult smoking, in terms of both overall prevalence and first use, suggest that this directed marketing is having an impact.14–16

This new marketing strategy may also have a political motivation. The patterns of development of this advertising in the 2 study cities, while generally similar, exhibited some differences. The main difference occurred in 1997, when the number of advertisements in the San Francisco Bay Guardian exceeded those in the Philadelphia City Paper by a weighted total of 47. This more intensive advertising in San Francisco may have been part of the tobacco industry's effort to counter the effects of California's smoke-free bar law, which was scheduled to go into effect in California in January 1998.30

The presence of these promotions in other states may help to impede the passage of smoke-free bar laws or create compliance problems. Similar studies that have quantified the emergence of bars as promotional venues may help to clarify any political motivations.40 In any event, the presence of the smoke-free bar law in California did not inhibit the tobacco industry's use of bars as promotional venues in San Francisco relative to Philadelphia.

During the decade of the 1990s, the public health community concentrated on making it politically difficult for the tobacco industry to target children, in the hope that if children did not begin to smoke before reaching the age of 18 years, they would never smoke. The tobacco industry appears to have responded to this situation by increasing its promotional efforts targeted to young adults. These efforts appear to be bearing fruit; smoking rates are increasing in this age group.14–16 It would be unfortunate if one result of the concentration on youth smoking of the past decade were simply that more people are smoking in young adulthood. The public health community needs to rethink its tobacco prevention strategies to account for these new industry strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant CA-61021 from the National Cancer Institute.

We thank Mamiko Hada for assistance in data collection.

Both authors participated in formulating the study, conducting the analysis, and writing and revising the manuscript. E. Sepe collected and coded the data.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Solomon C. Tobacco companies bankroll their own. Seattle Times. December 10, 1997:A1.

- 2.Scholtes PS. You're not invited. City Pages [serial online]. September 22, 1999.

- 3.Hwang SL. Tobacco companies enlist the bar owner to push their goods. Wall Street Journal. April 21, 1999:A1, A6.

- 4.Graham C. Tobacco companies heating up the nightclub scene. St. Petersburg Times. August 16, 1998:H1.

- 5.Gellene D. Joining the clubs: tobacco firms find a venue in bars. Los Angeles Times. September 25, 1997:D1, D3.

- 6.Davis HL. A party to die for? Buffalo News. July 27, 1998:A4–A5.

- 7.Carreon C. Joe Camel turns up in Portland nightclubs. The Oregonian [serial online]. July 31, 1998.

- 8.Glantz SA. Preventing tobacco use: the youth access trap. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:156–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy D, Cummings K, Hyland A. A simulation of the effects of youth initiation policies on overall cigarette usage. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1311–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi WS. Which adolescent experimenters progress to established smoking in the United States? Am J Prev Med. 1997;13:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flay BR, d'Avernas JR, Best JA, Kersell MW, Ryan KB. Cigarette smoking: why young people do it and ways of preventing it. Pediatr Adolesc Behav Med. 1983;10:132–183. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1994. [PubMed]

- 13.Sepe E, Ling P, Glantz S. Smooth moves: the targeting of young adults by the tobacco industry's bar and nightclub promotions Am J Public Health. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ehlinger EP. Boynton Health Service Announces Sharp Rise in Tobacco Use in University of Minnesota Students [press release]. Minneapolis: School of Public Health, University of Minnesota; 1999.

- 15.Emmons KM, Wechsler H, Dowdall G, Abraham M. Predictors of smoking among US college students. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:104–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wechsler H, Rigotti NA, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Increased levels of cigarette use among college students: a cause for national concern. JAMA. 1998;280:1673–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Dept of Health and Human Services. Incidence of initiation of cigarette smoking—United States, 1965–1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:837–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wizda S. Consider the alternative. Am Journalism Rev. November 1998:44.

- 19.Stein ML. Who's copying whom? (alternative papers believe mainstream papers are becoming more like them). Editor Publisher. 1998;131(8):3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnuer J. Older generations just don't get alternative lure. Advertising Age. April 20, 1998:S20.

- 21.Pollack J. Number of small publications continues to increase locally. St. Louis Journalism Rev. 1998;28:7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mollenkamp B. Alternative press goes corporate. St. Louis Journalism Rev. 1997;28:2. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giman W. Alternatives making inroads: consolidation among alternative newspapers is making them more than just a nuisance to many mainstream dailies in the battle for national ad dollars. Editor Publisher. 1997;130(22):3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giman W. “Sexier” and better looking: Association of Alternative Newsweeklies panelists say dailies are losing ground to their better packaged, more colorful weekly competitors. Editor Publisher. 1997;130(30):2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bates E. Chaining the alternatives. Nation. 1998;266:11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ardits SC. The alternative press: newsweeklies and zines. Database. 1999;22(3):15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alternative capitalism. Maclean'. February 23, 1998:13.

- 28.Macdonald HR, Glantz SA. The political realities of statewide smoking legislation. Tob Control. 1997;6:41–54.9176985 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magzamen SG. Turning the Tide: Tobacco Industry Political Influence and Tobacco Policy Making in California 1997–1999. San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco; 1999. Available at: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/ca9799. Accessed October 16, 2001.

- 30.Magzamen S, Glantz SA. The new battleground: California's experience with smoke-free bars. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 2000.

- 32.Gilpin EA, Lee L, Evans N, Pierce JP. Smoking initiation rates in adults and minors: United States, 1944–1988. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burns D, Lee L, Vaughn J, Chiu Y, Shopland D. Rates of smoking initiation among adolescents and young adults, 1907–81. Tob Control. 1995;4(suppl 1):S2–S8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novotny TE, Warner KE, Kendrick JS, Remington PL. Smoking by blacks and whites: socioeconomic and demographic differences. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1187–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Differences in the age of smoking initiation between blacks and whites—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:754–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giovino GA, Henningfield JE, Tomar SL, Escobedo LG, Slade J. Epidemiology of tobacco use and dependence. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17:48–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giovino GA, Schooley MW, Zhu BP, et al. Surveillance for selected tobacco-use behaviors—United States, 1900–1994. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1994;43(3):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Escobedo LG, Anda RF, Smith PF, Remington PL, Mast EE. Sociodemographic characteristics of cigarette smoking initiation in the United States: implications for smoking prevention policy. JAMA. 1990;264:1550–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauman K, Ennett S. Tobacco use by black adolescents: the validity of self-reports. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:394–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cruz T, Weiner M, Schuster D, Unger J. Growth of tobacco-sponsored bars and clubs from 1996–2000. Paper presented at: 128th Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; November 12–16, 2000; Boston, Mass.