Abstract

Objectives. This study determined the age group for the case definition of early adolescent childbearing based on rates of adverse clinical outcomes.

Methods. We examined rates of infant mortality, very low birthweight (<1500 g), and very preterm delivery (<32 weeks) per 1000 live births for all US singleton first births (n = 768 029) to women aged 12 to 23 years in the 1995 US birth cohort.

Results. Rates of infant mortality, very low birthweight, and very preterm delivery were graphed by maternal age. In all 3 cases, the inflection point below which the rate of poor birth outcome is lower and begins to stabilize is at 16 years; therefore, mothers 15 years and younger were grouped together to determine the case definition of early adolescent childbearing. The inflection points were similar when outcomes were stratified by the 3 largest US racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Mexican American).

Conclusions. From this population-based analysis of birth outcomes, we conclude that early adolescent childbearing is best defined as giving birth at 15 years or younger.

Childbearing in early adolescence is considered socially problematic in most cultures. In addition, many people believe that young adolescent mothers are at high risk for poor health outcomes during pregnancy and childbirth.1 Despite these 2 important concerns, relatively little research has examined the experience and characteristics of the youngest mothers. Studies characterizing adolescent childbearing typically limit their scope to mothers aged 15 to 19 years, whereas information about childbearing at younger ages usually appears only in aggregate national statistics.2 The few studies including early teenagers have reached mixed conclusions regarding the risks associated with childbearing at young ages. This uncertainty may reflect small sample size or inconsistencies in the age groups used to define early adolescent childbearing.3

Young mothers are difficult to study, in part because they have been a poorly defined group. The youngest teenage mothers have been cataloged into a variety of age groups, ranging from younger than 18 years to 13 years or younger.4–10 The inconsistencies in defining early adolescent childbearing have made comparisons across studies difficult. For example, it is unclear whether 15-year-olds who bear children should be included with adolescents 14 years and younger or if they should be included with those 16 years and older. Better definition of age groups may help to determine what factors, whether biological or social, put early adolescent mothers at higher risk.

Using the national vital statistics database to analyze birth outcomes, we asked the question “Who should be included in the early adolescent childbearing age group?” Once a case definition based on a specific age group is established, with a rationale based on differences in outcomes between childbearing age groups, future studies will be better able to assess specific pregnancy risks as well as the social and health needs of these young mothers.

METHODS

The 1995 US birth cohort contains all birth certificate vital statistics for births in the United States in 1995. This data set is provided by the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Center for Health Statistics. We used this birth cohort because it was the most recent cohort available at the time of this analysis that links birth certificates with infant death certificates.

We limited our analysis to the birth certificate data from all US singleton first births to mothers aged 12 to 23 years at the time of delivery (n = 768 029). We did not include ages higher than 23 years because we were attempting to derive comparable age groups along a continuum. Ages 11 years and younger were excluded because of the rare occurrence of childbearing at these ages (32 such births in the United States in 1995).

In the data file, infant deaths, defined as deaths occurring any time within the first year after birth, are linked to their respective birth certificates (n = 5957). Very low birthweight was defined as a weight of less than 1500 g at birth (n = 10 656). Very preterm delivery was defined as a gestational age of less than 32 weeks at birth (n = 15 653). Birth outcomes by maternal age were stratified by the 3 largest US racial/ethnic groups: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Mexican American.

We assessed inadequate prenatal care use by using the R-GINDEX measure for prenatal care use, which takes into account the onset of prenatal care, number of prenatal visits, and gestational age at birth.11,12 Tobacco use during pregnancy and any alcohol use during pregnancy were analyzed as dichotomous variables. Low maternal weight gain was defined as weight gain of 20 pounds or less during the pregnancy. Maternal anemia during the pregnancy was defined as a hemoglobin count of less than 10.0 g/dL or a hematocrit of less than 30%. The type of delivery (cesarean or vaginal) was also abstracted from the birth certificate. Missing variables were not included in the analysis (prenatal care [3% missing], tobacco use [20% missing], alcohol use [15% missing], maternal weight gain [21% missing], maternal anemia [1% missing]).

Bivariate comparisons between maternal age and rates of very low birthweight, infant mortality, and very preterm delivery were calculated and graphed with their associated standard errors. All rates were calculated per 1000 live births in that age group. Maternal age categories were determined on the basis of the graphical information from this analysis. Rates of maternal risk factors, along with their 95% confidence intervals, were calculated for the following risk variables: inadequate prenatal care use, tobacco use, alcohol use, low maternal weight gain, maternal anemia, and cesarean deliveries. Statistical significance between groups was tested by analysis of variance with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons. SAS version 6.12 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

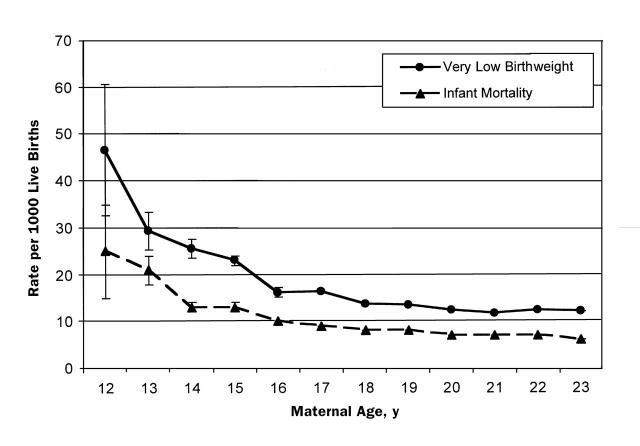

Rates of very low birthweight and infant mortality, along with their standard error bars, are shown in Figure 1 ▶. In the graph, 16 years of age is the inflection point at which the rates for both birth outcomes appear to stabilize at lower levels. The graph for very preterm delivery rates (not shown) also has an inflection point of 16 years. Together, these graphs show that 15-year-olds resemble younger adolescent mothers more closely than they resemble 16- to 19-year-old mothers. Taking this graphical information of medical outcomes into consideration, we propose that the age group definition for early adolescent childbearing be established as 15 years and younger. Using age groupings from this analysis, we found the rates of poor birth outcomes to be higher for those 15 years and younger (infant mortality = 13 per 1000 live births, very low birthweight = 24, very preterm delivery = 43) than for 16- to 19-year-olds (infant mortality = 8, very low birthweight = 15, very preterm delivery = 22) and 20- to 23-year-olds (infant mortality = 7, very low birthweight = 12, very preterm delivery = 16). These groups all differed significantly from one another (P < .01).

FIGURE 1.

—Rates of very low birthweight and infant mortality per 1000 live births.

Birth outcomes by maternal age were also stratified by the 3 largest racial/ethnic groups in the United States (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Mexican American). Although birth outcomes differed among these groups, the inflection point where the rates of infant mortality, very low birthweight, and very preterm delivery are lower and begin to stabilize is the same for each race/ethnicity: between ages 15 and 16 years (results not shown).

We next measured differences in traditional risk factors linked to poor birth outcomes and teenage childbearing among early adolescent mothers, older adolescent mothers (16–19 years old), and adult mothers (20–23 years old). Table 1 ▶ shows frequencies of inadequate prenatal care use, tobacco use, and alcohol use according to maternal age group. The mothers who were 15 years and younger had statistically higher rates of inadequate prenatal care use than both the 16- to 19-year-old mothers (P < .01) and the 20- to 23-year-old mothers (P < .01). The rate of tobacco use in the early adolescent group was statistically lower than the rate for older adolescents (P < .01). Further, the rate of low weight gain (<20 pounds during the pregnancy) was 16.8% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 16.4%, 17.2%) in the group 15 years and younger, 14.4% (95% CI = 14.3%, 14.5%) in the 16- to 19-year-old group, and 13.7% (95% CI = 13.6%, 13.9%) in the 20- to 23-year-old group. In regard to low weight gain, each of these groups differed significantly from one another (P < .01).

TABLE 1.

—Frequencies of Inadequate Prenatal Care Use, Tobacco Use, and Alcohol Use by Maternal Age Group

| Maternal Risk Factor, % (95% CI) | |||

| Maternal Age Group | Inadequate Prenatal Care Usea | Tobacco Useb | Alcohol Usec |

| ≤15 y (n = 40 388) | 22.7 (22.3, 23.1) | 10.2 (9.9, 10.5) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) |

| 16–19 y (n = 357 760) | 13.8 (13.7, 13.9) | 16.5 (16.4, 16.6) | 0.9 (0.9, 0.9) |

| 20–23 y (n = 369 881) | 9.3 (9.2, 9.3) | 13.9 (13.8, 14.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; n = total number of singleton first births in age category during 1995.

aInadequate prenatal care use is based on the R-GINDEX measure of prenatal care use.

bTobacco use during pregnancy.

cAlcohol use during pregnancy.

We also considered other medical risks often associated with teenage childbearing to determine whether they differed among the age groups. Childbearing among early adolescents was associated with higher frequencies of maternal anemia (3.0% [95% CI = 2.8%, 3.1%]) than among older adolescents (2.7% [95% CI = 2.6%, 2.7%]) and adults (2.0% [95% CI = 2.0%, 2.1%]). Cesarean delivery was less frequent among the early adolescents (13.2% [95% CI = 12.8%, 13.5%]) than among older adolescents (14.8% [95% CI = 14.7%, 14.9%]) and adults (19.0% [95% CI = 18.8%, 19.1%]). For all of these comparisons, differences were statistically significant (P < .01).

DISCUSSION

Our goal was to determine which maternal ages should be included in the definition of early adolescent childbearing on the basis of birth outcomes. We set out to determine whether there is a specific age cutpoint at which medical outcomes are worse for early adolescent mothers than for older adolescents and adults. Using the 1995 birth cohort, which includes all birth certificates linked to infant death certificates, we were able to establish an age group case definition for early adolescent childbearing based on rates of infant mortality, very low birthweight, and very preterm delivery. The analysis of birth outcomes by maternal age suggests that the definition of early adolescent childbearing should include mothers 15 years and younger at the time of the infant's birth, since the age at which poor birth outcome rates are lower and begin to stabilize is 16.

We considered alternative interpretations of the data. For example, looking at infant mortality in isolation, one might be tempted to suggest that another cutpoint exists between 13 and 14 years of age. When all 3 data sets are considered together, however, the best cutpoint appears to be between 15 and 16 years of age. On the basis of these associations with birth outcomes, it appears that adolescence encompasses at least 2 important maternal age groups. Although both adolescent age groups had poorer outcomes than the adult mothers in this study, the early adolescent childbearing age group (mothers 15 years and younger) had substantially higher rates of very low birthweight infants, very preterm infants, and infant deaths than the late adolescent age group (16- to 19-year-old mothers).

We chose to use infant mortality because it is a reliably measured birth outcome. In addition, birth certificate records have been established as reliable measures for birthweight.13 We used the variable very low birthweight instead of low birthweight because it is a more clinically significant outcome. Reporting of gestational age has been criticized as unreliable in vital statistics data,14 and there is the potential for more unreliable reporting for early adolescents since they have higher rates of inadequate prenatal care and possibly more irregularity to their menstrual cycles. However, the inflection point on the graph for rates of very preterm delivery is similar to those for rates of very low birthweight and infant mortality, which are not subject to the same reporting bias as gestational age. Using a database that includes the entire population from 1995 allowed us to consider these rare and clinically significant outcomes.

The reasons for higher rates of poor birth outcomes among young adolescents compared with older adolescents are not clear. We compared risks associated with childbearing to see if differences appeared between the early adolescent and the older adolescent mothers. Although the reliability in reporting these variables is questionable, the data suggest that early adolescent mothers have higher rates of both inadequate prenatal care use and inadequate weight gain than older teenage mothers. Obviously, there are many possible explanations for decreased prenatal care use and poor prenatal weight gain. Both of these risk markers have been associated with increased exposure to physical violence before and during pregnancy,15–17 and we need to investigate the importance of these risks in the early adolescent childbearing age group.

In contrast to the higher rates of inadequate prenatal care use, early adolescent mothers have lower rates of reported tobacco and alcohol use during pregnancy. This may surprise some investigators. Risk-taking behavior has been frequently associated with teenaged childbearing18; however, we know relatively little about risk-taking behavior in younger adolescent childbearing. It is not possible to draw conclusions about the rates of risk behaviors on the basis of vital statistics data; however, we should consider that the traditional risk factors associated with teenage childbearing might not be expressed with the same frequency or to the same degree in early adolescent mothers. Furthermore, other, as yet unappreciated risk factors in early adolescence may put these young mothers at higher risk for poor birth outcomes.

The risks associated with delivery also differ between early adolescent mothers and their older teenage counterparts. Early adolescent mothers had lower rates of cesarean delivery than older adolescent mothers and adults. Early adolescent mothers had higher rates of maternal anemia, which is probably associated with poor nutritional status.19 A theory of biological immaturity has been cited as a global explanation for the increased risk for poor birth outcomes in early adolescent mothers.6,9,20 If biological immaturity accounted for the greatest proportion of risk, however, we would expect the rates of cesarean delivery to be higher in this population because of a theoretical underdevelopment of the bony pelvis and uterus.21 Although biological immaturity may partly explain poor birth outcomes, biology alone seems inadequate to account for all of the associated increased risk. Because of the limited information available in national vital statistics data, this study focused mainly on infant outcomes, with only limited attention placed on maternal health outcomes, and therefore many questions are left unanswered. Differences in exposure to violence, socioeconomic status, stress, depression, and motivational characteristics cannot be assessed from birth certificate data.

Previous studies have inconsistently defined early adolescent childbearing and have rarely included a rationale for choosing specific ages to include in their analyses. The primary strength of this study is that we were able to ascertain an appropriate age group for the case definition of early adolescent childbearing based on meaningful birth outcomes from the inclusive 1995 US birth cohort. The age group definition established by this method provides a basis for further in-depth analysis.

With 40 000 births to adolescents 15 years and younger in the United States each year, a significant number of vulnerable mothers and children suffer the consequences of early adolescent childbearing. Characterizing and understanding the differences in risk profiles between early adolescent mothers and older adolescent mothers will allow us to develop more specific programs and policies to help these young women. In light of the knowledge that early adolescents do not have the same risk factors or outcomes as older adolescents, we should not expect the present programs targeting “teen pregnancy” to be the most effective way to help the youngest mothers. At this point, we do not know what specifically makes an early adolescent and her child at higher risk for poor birth outcomes; the circumstances surrounding conception, the prenatal course, and the postpartum situation in early adolescent mothers should be carefully and thoughtfully explored. If we are to improve the experiences of young mothers and their children, we must better understand the social, biological, and medical circumstances surrounding this high-risk age group. Adopting a standardized age group based on well-defined birth outcomes may facilitate future investigation.

Acknowledgments

M. G. Phipps completed this research while participating as a research fellow in the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program at the University of Michigan.

M. G. Phipps planned the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the report. M. F. Sowers contributed to the data analysis and the writing.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Luker K. Dubious Conceptions: The Politics of Teenage Pregnancy. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1996.

- 2.Ventura SJ, Mathews TJ, Curtin SC. Declines in teenage birth rates, 1991–1998: update of national and state trends. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 1999;47(26):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper LG, Leland NL, Alexander G. Effect of maternal age on birth outcomes among young adolescents. Soc Biol. 1995;42:22–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berenson AB, Wiemann CM, McCombs SL. Adverse perinatal outcomes in young adolescents. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:559–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown HL, Fan YD, Gonsoulin WJ. Obstetric complications in young teenagers. South Med J. 1991;84:46–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser AM, Brockert JE, Ward RH. Association of young maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1113–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horon IL, Strobino DM, MacDonald HM. Birth weights among infants born to adolescent and young adult women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;146:444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormick MC, Shapiro S, Starfield B. High-risk young mothers: infant mortality and morbidity in four areas in the United States, 1973–1978. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reichman NE, Pagnini DL. Maternal age and birth outcomes: data from New Jersey. Fam Plann Perspect. 1997;29:268–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoder BA, Young MK. Neonatal outcomes of teenage pregnancy in a military population. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Quantifying the adequacy of prenatal care: a comparison of indices. Public Health Rep. 1996;111:408–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kogan MD, Martin JA, Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M, Ventura SJ, Frigoletto FD. The changing pattern of prenatal care utilization in the United States, 1981–1995, using different prenatal care indices. JAMA. 1998;279:1623–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piper JM, Mitchel EF Jr, Snowden M, Hall C, Adams M, Taylor P. Validation of 1989 Tennessee birth certificates using maternal and newborn hospital records. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:758–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooperstock M. Gestational age-specific birthweight of twins in vital records. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1998;12:347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens-Simon C, McAnarney ER. Childhood victimization: relationship to adolescent pregnancy outcome. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18:569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dietz PM, Gazmararian JA, Goodwin MM, Bruce FC, Johnson CH, Rochat RW. Delayed entry into prenatal care: effect of physical violence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berenson AB, Wiemann CM, Rowe TF, Rickert VI. Inadequate weight gain among pregnant adolescents: risk factors and relationship to infant birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1220–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geronimus AT, Korenman S. Maternal youth or family background? On the health disadvantages of infants with teenage mothers. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gadowsky SL, Gale K, Wolfe SA, Jory J, Gibson R, O'Connor DL. Biochemical folate, B12, and iron status of a group of pregnant adolescents accessed through the public health system in southern Ontario. J Adolesc Health. 1995;16:465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olausson PO, Cnattingius S, Haglund B. Teenage pregnancies and risk of late fetal death and infant mortality. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duenhoelter JH, Jimenez JM, Baumann G. Pregnancy performance of patients under fifteen years of age. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]