Abstract

Objectives. To improve tobacco control campaigns, we analyzed tobacco industry strategies that encourage young adults (aged 18 to 24) to smoke.

Methods. Initial searches of tobacco industry documents with keywords (e.g., “young adult”) were extended by using names, locations, and dates.

Results. Approximately 200 relevant documents were found. Transitions from experimentation to addiction, with adult levels of cigarette consumption, may take years. Tobacco marketing solidifies addiction among young adults. Cigarette advertisements encourage regular smoking and increased consumption by integrating smoking into activities and places where young adults' lives change (e.g., leaving home, college, jobs, the military, bars).

Conclusions. Tobacco control efforts should include both adults and youths. Life changes are also opportunities to stop occasional smokers' progress to addiction. Clean air policies in workplaces, the military, bars, colleges, and homes can combat tobacco marketing. (Am J Public Health. 2002;92:908–916)

Virtually all tobacco control programs emphasize primary prevention for children and teens or smoking cessation for adult smokers. Tobacco control efforts aimed at young adults (aged 18–24 years) are generally limited to cessation for pregnant women,1–8 military personnel,9–14 or college students.15–17 Despite the widely accepted view that smoking initiation occurs only before age 18, smoking frequently began during young adulthood in the early and mid-20th century and still does among some ethnic groups.18–21 Rates of current cigarette use among young adults increased steadily, from 34.6% in 1994 to 41.6% in 1998,20 and then declined slightly, to 39.7% in 1999 and to 38.3% in 2000.22 The prevalence of current smoking among college students increased from 22.3% in 1993 to 28.5% in 1998.23

The number of young people at moderate to high risk for established smoking increases throughout the teen years, with more people in the early stages of smoking initiation (open to smoking, experimenting, and nonregular smoking) at ages 14 to 19 than at 11 to 14.24 The number of 18- to 19-year-olds in the early stages of smoking initiation is more than twice the number of 18-year-old established smokers.24 These youths are at risk to become established smokers as young adults and thus are prime targets for interventions to make them nonsmokers again.

Since 1998, more than 40 million pages of previously secret tobacco industry documents have been made available to the public. Previous investigations with these documents concentrated on proving that tobacco industry marketing targeted youths.25–27 We analyzed the documents to find why and how the tobacco industry markets to young adults and drew 3 conclusions. First, the industry views the transition from smoking the first cigarette to becoming a confirmed pack-a-day smoker as a series of stages28–30 that may extend to age 25,31 and it has developed marketing strategies not only to encourage initial experimentation (often by teens) but also to carry new smokers through each stage of this process.28,32–36 Second, industry marketers encourage solidification of smoking habits and increases in cigarette consumption by focusing on key transition periods when young adults adopt new behaviors—such as entering a new workplace, school, or the military–and, especially, by focusing on leisure and social activities.33,37,38 Third, tobacco companies study young adults' attitudes, social groups, values, aspirations, role models, and activities and then infiltrate both their physical and their social environments.37,39–43 Understanding this process can help public health practitioners to develop better tobacco control programs and physicians to encourage nonsmoking among young adult patients.

METHODS

We searched tobacco industry document archives from the University of California–San Francisco's collection of R. J. Reynolds (RJR) and British American Tobacco marketing documents (http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco), tobacco industry document Web sites (Philip Morris: http://www.pmdocs.com; Brown and Williamson: http://www.brownandwilliamson.com; RJR: http://www.rjrtdocs.com' Lorillard: http://www.lorillarddocs.com), and Tobacco Documents Online (http://www.tobaccodocuments.org). Initial search terms included the following: young adults, younger adult, new smokers, marketing, advertising, college, bars, military, Generation X, industry terms for young adult smokers (such as “YAFS,” a Philip Morris abbreviation for Young Adult Female Smokers), lifestyle, motivation, strategy, and brand names.

Initial searches yielded thousands of documents. Applying standard techniques,44 we repeated and focused the searches. We also conducted further searches for contextual information on relevant documents by using their names, locations, dates, and reference (Bates) numbers. This analysis is based on a final collection of approximately 200 marketing research reports, questionnaires, memorandums, and plans. We found most of the documents in the Philip Morris, Lorillard, and RJR collections; these companies also own the brands most popular among young people (Marlboro, Camel, and Newport).22,45 Although the tobacco industry has used “younger adult smoker” as a code word to disguise efforts to recruit teenage smokers,46 we limited this analysis to tobacco industry documents that explicitly discussed 18- to 24-year-olds or young adult activities, such as military service, college, or going to bars.

RESULTS

Tobacco Industry Efforts to Encourage Smoking Span Youth and Adulthood

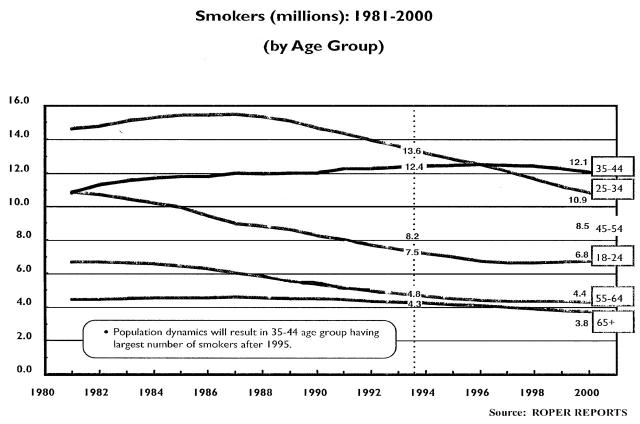

Tobacco marketers regard smoking initiation as a process that begins among teenagers but that must be cultivated among young adults. Not only does the tobacco industry encourage youths to start smoking, but its efforts to reinforce smoking continue well into adulthood.34 In contrast to public health's concentration on youth, the tobacco industry tracks smokers in every age group (Figure 1 ▶). Philip Morris's 1993 projections of the smoking population estimated that there would be 6.8 million young adult smokers in 2000—more than double the number of teen smokers in public health estimates.24,47

FIGURE 1.

—A 1993 Philip Morris document showing numbers of smokers by age group from 1981 to 2000 (projected).

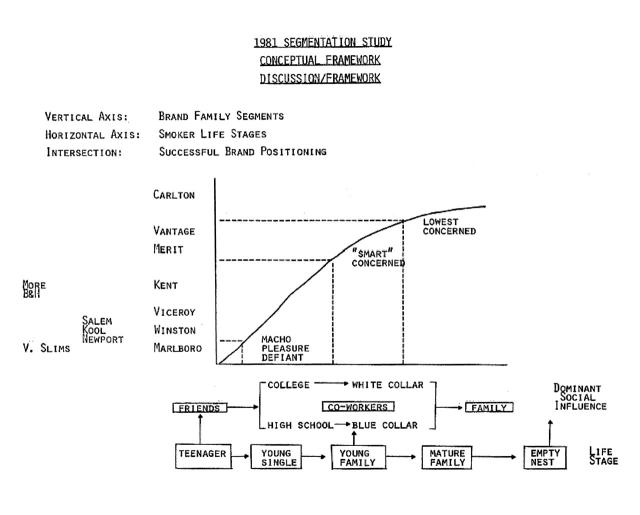

Like tobacco marketers, public health researchers portray smoking initiation as a progression of stages.45,48 For more than 30 years, tobacco industry researchers have also used models presenting the creation of an addicted smoker in a series of stages, each with different needs and motivations, and have developed marketing strategies to move people through this process. For example, in 1973, RJR strategist Claude Teague illustrated how the young smoker progresses from “pre-smoker” to “learner” to “confirmed smoker” in a model less sophisticated than but similar to later public health models (Figure 2 ▶). He advised that tobacco marketing should match each stage in this process.28

FIGURE 2.

—Comparison of tobacco industry model (1973 R. J. Reynolds document28) and public health model (1994 Surgeon General's Report45) of smoking initiation.

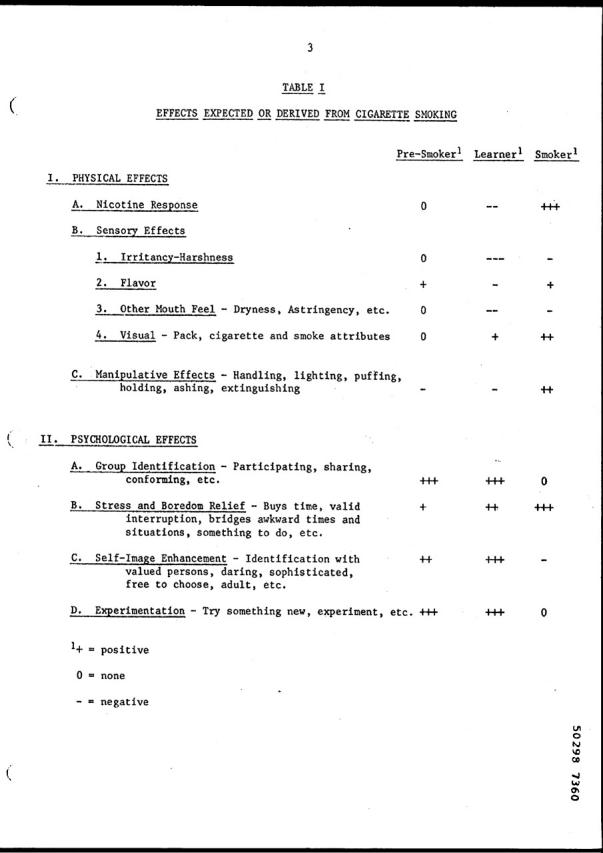

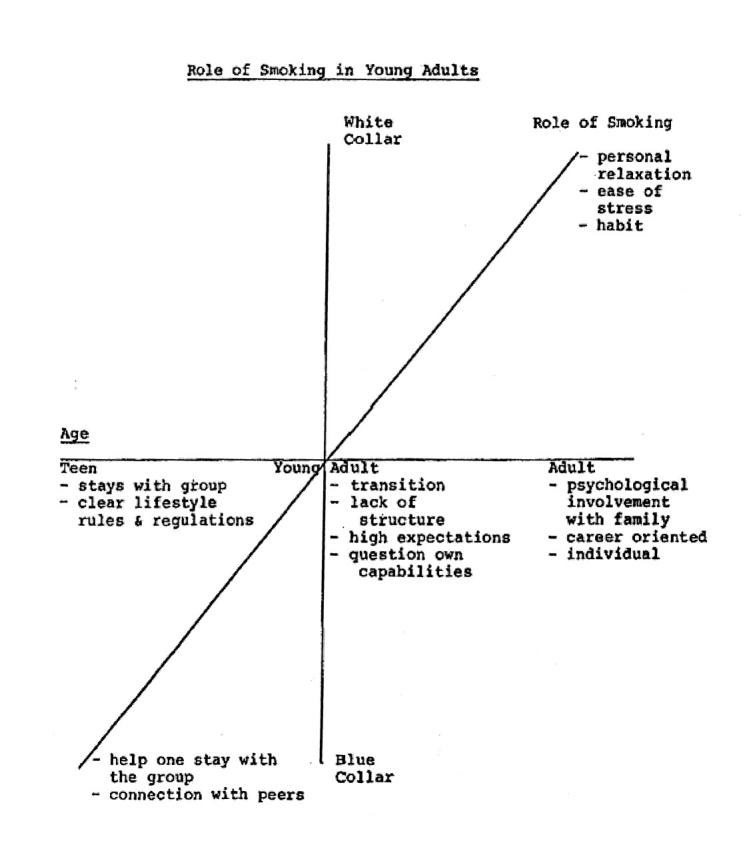

Another 1985 report written for RJR explained how smoking evolves from a social means of connecting with peers in the teenage years to become a habitual response to stress or boredom in adulthood (Figure 3 ▶).33 The report illustrates the changing role of smoking for young adults:

These years of transition represent a shift between the comfort of the high influence of the peer group, and relative structure in life, to the development of one's own personal, social and occupational goals. For some, smoking seems to fulfill the function during teens of uniting one with the all-important peer group. In adulthood, it may be used to ease the feelings of stress created by the pursuit of one's goals. Smoking, for a young adult, may fulfill both roles, providing a concrete balance at a time when life is chaotic and stressful. It represents both the ties with the “old days” and “old friends,” as well as the more mature instrument for relaxing.33

FIGURE 3.

—A 1985 R. J. Reynolds document illustrating different roles of smoking for teens, young adults, and adults.

Similar strategies based on stage models of smoking were developed by several tobacco companies and their consultants in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.30,32,34,37,39 One Philip Morris researcher noted in a 1981 report that “the overwhelming majority of smokers first begin to smoke while still in their teens. In addition, the ten years following the teenage years is the period during which average daily consumption per smoker increases to the average adult level.”29 Both RJR and Philip Morris developed cigarette brands for each stage of smoking, including these later stages.32,34,49 For example, in 1994, Philip Morris's advertising agency, Young & Rubicam, presented the following model to illustrate evolution of brand choice as the young adult smoker matures:

Choice of “starter” brand → youthful conformity/rebellion

“Break-away” brand → early maturation: individuation and self-assertion

Choice of “mature” brand(s) → later maturation: self-management/tradeoffs32

Young & Rubicam recommended that Philip Morris position Chesterfield to appeal to young adults who were approaching a life transition that involved increasing “individuation and self-assertion”:

Who Are We Talking To: Young Adult Male Smoking Enthusiasts, 18–24, who no longer want to be labeled as one of the crowd. They resist peer group pressure, and therefore are open to an alternative to Marlboro. As smokers, our target lives in a climate of exile and disapproval. They view smoking as part of their choice, their individuality, their self-expression. “Not Your First” capitalizes on our target's desire for individualistic style—and intense experiences—while dramatizing Chesterfield's superior smoking pleasure.32 [Emphasis in original]

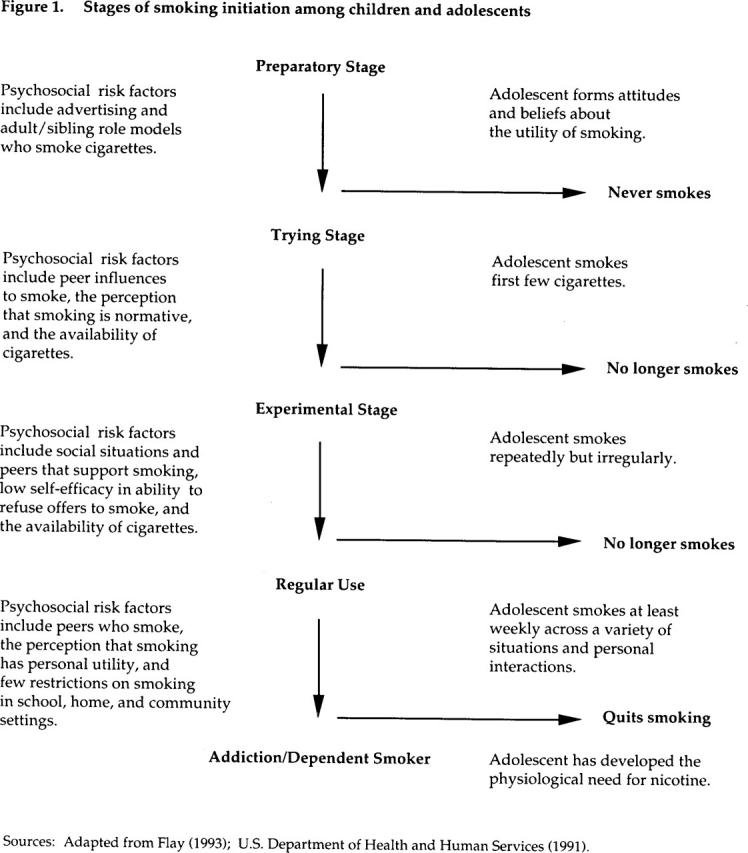

Not only is tobacco marketing designed to cultivate smokers throughout the process of smoking initiation; brands are also positioned for established smokers who are thinking seriously about quitting, such as those who are concerned about health and the financial costs of smoking.50,51 Examination of an RJR 1981 segmentation study presentation reveals how brands were positioned for each life stage (Figure 4 ▶).34 RJR attempted to match a brand image—such as “macho, strong and masculine” or “low tar, health concerned”—to the smoker's life stage.34

FIGURE 4.

—A 1981 R. J. Reynolds document that positions cigarette brands to match each stage of life.

Young Adulthood Provides Opportunities to Solidify Addiction

Young adults are particularly important to the industry for several reasons. First, the progression from “experimenter” to “mature” smoker is accompanied by an important increase in consumption.29 Second, young adults face multiple life transitions that provide opportunities for adoption and solidification of smoking as a regular part of new activities.36 Third, the stresses of these life transitions invite the use of cigarettes for the drug effects of nicotine.36

Tobacco marketers investigated how changes in friends, family, and work are linked to smoking among young adults. In 1982, a Philip Morris researcher described how changes in young people's lives make them more likely to switch brands and to increase cigarette consumption:

Life passages are major, milestone events in a person's life which can significantly affect the quality and content of the person's life from that day forward. One can imagine a young man or woman experiencing these changes as they age and mature. . . . a significant number of people are experiencing changes in their lives, and these people are volatile in their smoking behavior: They are more likely to switch and increase consumption.52

Each “life passage” provides an opportunity for the tobacco marketer to introduce and solidify smoking. As Philip Morris advertising consultants Young & Rubicam noted in 1994, “significant choice moments in cigarette smoking tend to coincide with critical transition stages in life.”32

In addition, tobacco marketers knew that such “life passages” were stressful and that these periods were an opportune time to take advantage of the pharmacological effects of nicotine. In young adulthood, smoking increasingly becomes a way to deal with the stresses of life:

A young adult is leaving childhood on his way to adulthood. He is leaving the security and regiment of high school and his home. He is taking a new job; he is going to college; he is enlisting in the military. He is out on his own, with less support from his friends and family. These situations will be true for all generations of younger adults as they go through a period of transition from one world to another. . . . Dealing with these changes in his life will create increased levels of uncertainty, stress and anxiety. . . . During this stage in life, some younger adults will choose to smoke and will use smoking as a means of addressing some of these areas.36

The tobacco industry has known since at least the 1960s that the pharmacological effects of nicotine are “most rewarding to the individual under stress”53 and that nicotine is “an addictive drug effective in the release of stress mechanisms.”54

A 1976 Philip Morris internal memorandum summarizing secondary sources of data on smoking initiation noted that stress may encourage nonsmokers to start smoking and may prompt occasional smokers to smoke more:

Stressful situations occurring in an environment favorable to smoking may contribute to the starting of the smoking habit, as well as to its continuation. For instance, some men begin smoking in the tense days of their first job. Smokers consistently report that they tend to smoke more when under tension.35

Tobacco company research has also shown that people use cigarettes “as a tranquilizer” during stressful times.30,35

While they are learning to smoke, young adults may increasingly use cigarettes in response to stress, a practice that invites higher consumption:

For young adults who smoke, the use of cigarettes is seen as a mechanism to help ease the stress of transition from teen years to adulthood. The psychological role smoking plays for these young adults can be compared and contrasted with its use for teens and also for adults.

Smoking is now used to help meet the stresses of daily life,

Many are smoking more cigarettes now than they did in their teens.33

Ironically, much of the stress that cigarettes relieve is caused by nicotine withdrawal; it is common for people who stop smoking, once they are past withdrawal, to feel less stress than they experienced while smoking.55 The use of smoking for “stress relief” as supported by tobacco marketing is really self-medication for nicotine withdrawal.

Importance of the Physical and Social Environment in Appeal to Young Adults

A 1993 study for Philip Morris elucidated the importance of the environment in promoting smoking among young adults. In this study, 1564 smokers aged 18 to 24 years were surveyed about their concerns, beliefs, norms, values, leisure activities, and socialization patterns. Participants' responses were analyzed to identify common behavioral groups and the major forces affecting smoking behavior.37 The report noted that for young smokers, activities may be more important “drivers” of behavior than attitudes:

For instance among youngsters, males or females indifferently, the high level of involvement in activities obviously constitutes the driver. No matter what they think, no matter how they are perceived, [young people] act first. The behavior overwhelmingly shapes values, so that norms do not even show up. The engagement in specific situations (parties, beach . . .) is the only thing which counts. As a result, the concept of goodness and badness is not even relevant at this age, which translates it as Fun and Sex vs the rest.37 [Emphasis in original]

The author of this report emphasized that activities are particularly important “in a new environment (away from where one grew up, in a larger city, at college, in the army…)” because although the old rules of childhood have ceased to operate, the young person has not yet developed a new set of rules to direct his or her behavior. At this time, the immediate environment is a powerful influence:

Briefly said, the role of the environment appears determinant since it leads to and designs behaviors, which by itself implies a certain type of socialization, a natural selection of whom smokers socialize with. Classically, repeated accidental marketing exposure would be very efficient at favoring contexts where those behaviors can then take place.37 [emphasis in original]

Tobacco marketers were also aware that social environments can encourage increased consumption; one researcher noted that the friendly social ambiance of a pub or social club “contributes a great deal to enjoyment of smoking and also encourages smokers to smoke more heavily than usual.”30 This understanding of young adult behavior helps to explain why tobacco marketing strategies for young adults emphasize integration with the activities and environments of young adults, including work, military service, college, and especially bars and nightclubs.33,38,56–59

Philip Morris, RJR, and Lorillard's studies of young adult smokers all emphasize smokers' social activities and leisure interests. For example, the profiles of young adult male smokers (“YAMS”) aged 18 to 24 years developed for Philip Morris in 1990 explored how smoking different cigarette brands corresponded to 46 different social activities and 22 kinds of music.43 Detailed tobacco industry studies of the goals, aspirations, activities, and psychology of young adult smokers were used to target advertising at groups with similar attitudes.51 In addition, tobacco industry advertising agencies have conducted extensive research on young adult trends, music, icons, language, media usage, politics, and purchasing habits for Philip Morris, RJR, and Lorillard.30,32,49,56,60–66

Integration of their products with young adult activities provides tobacco companies with critical currency among their target audience. RJR focused on music and social activities in its brainstorming efforts to reach 18- to 20-year-olds.67 A 1994 proposal for Lorillard for an advertising campaign aimed at young adults also acknowledged the importance of the physical environment in a list of concepts expected to elicit a positive response in the target audience:

Irreverence and sassiness. Fun, hip and honest communications that say “we know.” Communications must VIOLATE THE RULES.

Escapist fantasies. Travel and entertainment are key themes.

Instant gratification: they want what they want—NOW!

Interactivity: talk with them, not at them. 800# promotions do well with this group.

“Egonomics”—marketing to the “me,” which means that anything personalized or customized to the individual does very well; the implications for direct marketing and place-based marketing are clear. Brands must be where their audience is—physically as well as emotionally.61

Tobacco industry sponsorship of music and sporting events, bar promotions, and parties all work to associate smoking with normal adult life.38,59 A 1985 proposal written for Lorillard targeted young adult smokers in Boston through their physical environment and social activities by focusing on Kenmore Square, where the ballpark and nightclubs formed “a social nerve center for the target demographic.”63 Feedback from Newport smokers suggested to Lorillard that portrayal of realistic and aspirational activities in Newport advertisements would heighten their relevance to this audience.68

DISCUSSION

During the critical years of young adulthood, public health efforts dwindle at the same time that tobacco industry efforts intensify. Young adults are an important target for the tobacco industry, particularly because they face major changes in their lives. The industry studies young adult attitudes, lifestyles, values, aspirations, and social patterns with a view toward making smoking a socially acceptable part of young adults' new activities.

In spite of the industry's claim that it does not market to nonsmokers, the marketing plans for young adults enable the industry to recruit new smokers between the ages of 18 and 24 years and to encourage light, occasional, or experimenting smokers to smoke more regularly.28,33,34 Young adults are also the youngest legal marketing target in an industry that depends on beginning smokers,69 and they vastly outnumber teen smokers.22,24,29,47 Furthermore, young adult marketing promotes smoking to older teens, who see young adults as their primary role models.28,30,70

Beginning in the 1990s, the tobacco industry increased the use of age-specific promotions, such as bar promotions and sponsored activities aimed at young adults.38,59 It has also opposed smoke-free bars to protect bars as promotional venues71; in addition, the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (which resolved state lawsuits against the tobacco industry) included provisions that explicitly exempted marketing in “adult-only facilities” from its limitations on industry activities.72

These industry strategies suggest new directions for tobacco control. Young adult life events such as beginning a new job, going away to college, starting a family, entering the military, or starting to socialize in bars are opportunities for the tobacco industry to encourage smoking. These transitions are also opportunities for public health programs to intervene and block the process leading to creation of confirmed daily smokers. To date, however, the public health community has left tobacco marketing in these arenas largely unopposed. Most smoking prevention efforts for young adults have focused on pregnant women smokers, who make up less than 2% of young adults and less than 12% of young adult female smokers.22,73,74

Public health efforts should apply successful tobacco control strategies to match the tobacco industry's interest in young adults and should develop new interventions to discourage occasional or light smokers from progressing to addiction. Although not specifically targeted toward young adults, some of the regulatory interventions have affected this important group. For example, cigarette taxes also decrease smoking rates, and they have their greatest effect on teens and young adults.75,76 Smoke-free workplaces encourage smokers to quit or cut down77–79; they probably also prevent young-adult occasional smokers entering the workforce from progressing to addiction. Smoke-free bars and nightclubs can help to break the associations between adult social patterns, alcohol use, and smoking cultivated by tobacco promotions. Smoke-free campus housing is associated with lower smoking rates among college students.80 Smoke-free homes are associated with increased quitting, decreased relapse, and lighter cigarette consumption,79,81 particularly when a nonsmoking adult or a child resides in the home.82,83 Educating young adults about the dangers of secondhand smoke may be especially effective because they are starting new households and new families. Educating young adult parents (and parents-to-be) about the dangers of secondhand smoke not only will provide benefits for the new child (who will avoid the morbidity associated with involuntary smoking84) but also may prompt cessation among the adults.

Although our analysis concentrates on industry efforts to solidify the smoking habit among young adults, it does not dispute the worth of smoking cessation and addiction treatment among smokers of all ages. Tobacco control efforts should be tailored to each age, as are tobacco marketing efforts. Media campaign messages about secondhand smoke and tobacco industry manipulation are effective for adults and youths85 and have played an important role in reducing both smoking and heart disease death rates in California.86,87 Countermarketing campaigns developed with careful attention to the audience's underlying motivations, such as those used in the Florida and American Legacy Foundation truth campaigns,88 may also be useful in developing messages for adults. Media messages supporting clean air policies may also erode the social acceptability of smoking that tobacco companies so carefully work to build and protect.89,90

The tobacco industry has for many years appreciated the importance of the period of young adulthood in establishing the addicted pack-a-day smoker. Public health programs targeting children and adolescents may only delay smoking initiation,91,92 leaving these people vulnerable to industry marketing as young adults. The tobacco industry has long been aware that “anti-smoking attitudes the [children] have learned in school and elsewhere can be unlearned or replaced by pro-smoking norms held by others their own age or a little older.”70 Working to delay smoking initiation among youths while allowing it to continue among young adults has little long-term benefit. Although important, primary prevention is not the only way to reduce the damage tobacco causes; while never smoking is obviously the most desirable situation, stopping smoking before age 30 eliminates virtually all of the long-term mortality effects.93 It is time for the medical and public health communities to follow the tobacco industry's lead and develop individual and communitywide interventions to block the process of initiating and solidifying smoking among young adults. The same life situations that have proven so fruitful for the tobacco industry are equally promising targets for health interventions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant T32 MH-19105), and the National Cancer Institute (grant CA-87472).

All authors contributed to the conception and writing of the manuscript. P. M. Ling located most of the industry documents.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Orleans CT, Johnson RW, Barker DC, Kaufman NJ, Marx JF. Helping pregnant smokers quit: meeting the challenge in the next decade. West J Med. 2001;174:276–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ershoff DH, Mullen PD, Quinn VP. A randomized trial of a serialized self-help smoking cessation program for pregnant women in an HMO. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartmann KE, Thorp JM Jr, Pahel-Short L, Koch MA. A randomized controlled trial of smoking cessation intervention in pregnancy in an academic clinic. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:621–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gielen AC, Windsor R, Faden RR, O'Campo P, Repke J, Davis M. Evaluation of a smoking cessation intervention for pregnant women in an urban prenatal clinic. Health Educ Res. 1997;12:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Secker-Walker RH, Solomon LJ, Flynn BS, Skelly JM, Mead PB. Reducing smoking during pregnancy and postpartum: physician's advice supported by individual counseling. Prev Med. 1998;27:422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lando HA, Valanis BG, Lichtenstein E, et al. Promoting smoking abstinence in pregnant and postpartum patients: a comparison of 2 approaches. Am J Manage Care. 2001;7:685–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wisborg K, Henriksen TB, Jespersen LB, Secher NJ. Nicotine patches for pregnant smokers: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:967–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon LJ, Secker-Walker RH, Flynn BS, Skelly JM, Capeless EL. Proactive telephone peer support to help pregnant women stop smoking. Tob Control. 2000;9(suppl 3):III72–III74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurtado SL, Conway TL. Changes in smoking prevalence following a strict no-smoking policy in US Navy recruit training. Mil Med. 1996;161:571–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bushnell FK, Forbes B, Goffaux J, Dietrich M, Wells N. Smoking cessation in military personnel. Mil Med. 1997;162:715–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helyer AJ, Brehm WT, Gentry NO, Pittman TA. Effectiveness of a worksite smoking cessation program in the military. Program evaluation. AAOHN J. 1998;46:238–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpenter CR. Promoting tobacco cessation in the military: an example for primary care providers. Mil Med. 1998;163:515–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conway TL. Tobacco use and the United States military: a longstanding problem. Tob Control. 1998;7:219–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clements-Thompson M, Klesges RC, Haddock K, Lando H, Talcott W. Relationships between stages of change in cigarette smokers and healthy lifestyle behaviors in a population of young military personnel during forced smoking abstinence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:1005–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black DR, Loftus EA, Chatterjee R, Tiffany S, Babrow AS. Smoking cessation interventions for university students: recruitment and program design considerations based on social marketing theory. Prev Med. 1993;22:388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh MM, Hilton JF, Masouredis CM, Gee L, Chesney MA, Ernster VL. Smokeless tobacco cessation intervention for college athletes: results after 1 year. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:228–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christie-Smith D. Smoking-cessation programs need to target college students. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilpin EA, Lee L, Evans N, Pierce JP. Smoking initiation rates in adults and minors: United States, 1944–1988. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Differences in the age of smoking initiation between blacks and whites—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:754–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Summary of Findings From the 1998 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, Md: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; August 1999. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/oas/NHSDA/NHSDAsumrpt.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2001.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR CDC Surveillance Summaries. Surveillance for Selected Tobacco-Use Behaviors—United States, 1900–1994. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43:. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Summary of Findings From the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, Md: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; September 2001. Report No. SMA 01–3549. Available at: http://www.drugabusestatistics.samhsa.gov. Accessed November 1, 2001.

- 23.Wechsler H, Rigotti NA, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Increased levels of cigarette use among college students: a cause for national concern [published erratum appears in JAMA.1999; 281:136]. JAMA. 1998;280:1673–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.First Look Report 3. Pathways to Established Smoking: Results From the 1999 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Washington, DC: American Legacy Foundation; October 2000. Report No. 3.

- 25.Pollay RW. Targeting youth and concerned smokers: evidence from Canadian tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2000;9:136–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perry CL. The tobacco industry and underage youth smoking: tobacco industry documents from the Minnesota litigation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hastings G, MacFadyen L. A day in the life of an advertising man: review of internal documents from the UK tobacco industry's principal advertising agencies [see comments]. BMJ. 2000;321:366–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teague CE. Research planning memorandum on some thoughts about new brands of cigarettes for the youth market. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. February 2, 1973. Bates No. 502987357 -7368. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com, www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/mangini. Accessed December 1, 2000.

- 29.Johnston ME, Daniel BC, Levy CJ. Young smokers prevalence, trends, implications, and related demographic trends. Philip Morris USA. March 31, 1981. Bates No. 1000390803/0855. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed December 5, 2000.

- 30.Hugh Bain Research. The psychology and significant moments and peak experiences in cigarette smoking. British American Tobacco Company. November 1993. Bates No. 500237804–7890. Available at: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco. Accessed April 16, 2001.

- 31.Hall LW. Early warning system input—reasons for smoking, initial brand selection, and brand switching. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. October 25, 1976. Bates No. 501103147 -3150. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com. Accessed February 4, 2002.

- 32.Young & Rubicam. Chesterfield. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. March 24, 1994. Bates No. 2500086977/7024. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed June 7, 2001.

- 33.Business Information Analysis Corporation. RJR young adult motivational research. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. January 10, 1985. Bates No. 502780379 -0424. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com, www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/mangini. Accessed December 12, 2000.

- 34.Author unknown. 1981 segmentation study. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. 1981. Bates No. 501233021 -3038. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com. Accessed March 5, 2001.

- 35.Udow A. Why people start to smoke. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. June 2, 1976. Bates No. 2042789380/9387. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed December 15, 2000.

- 36.Harden RJ. A perspective on appealing to younger adult smokers. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. February 2, 1984. Bates No. 502034940 -4943. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com, www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/mangini. Accessed December 12, 2000.

- 37.Author unknown. Young adult male smokers and young adult female smokers. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. November 1993. Bates No. 2045180640/0775. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed August 30, 2000.

- 38.Sepe E, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Smooth moves: bar and nightclub tobacco promotions that target young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:414–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Author unknown. 1985 segment description study—aging issues. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. 1985. Bates No. 508550616–0667. Available at: http://galen.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/mangini/html/j/005/otherpages/allpages.html. Accessed August 17, 2000.

- 40.R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. RJRTC 1991–1995 strategic plan. August 1990. Bates No. 513330214 -0338. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com. Accessed August 24, 2000.

- 41.Fields TF. Working class vs apirational mindsets: influence of demographics. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. January 15, 1986. Bates No. 504098434. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com. Accessed July 26, 2001.

- 42.Harden RJ. First usual brand younger adult smoker media and promotion exploratory. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. February 20, 1985. Bates No. 507174907 -4951. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com. Accessed October 17, 2001.

- 43.Michael Normile Marketing. Young adult smokers opportunity profiles. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. August 1990. Bates No. 2043102805/2944. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed September 7, 2000.

- 44.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? [comment in: Tob Control.2000; 9:261–262]. Tob Control. 2000;9:334–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: US Dept of Health and Human Services; July 1994.

- 46.Cummings KM, Morley C, Horan J, Steger C, Leavell N. Marketing to America's youth: evidence from corporate documents. Tob Control. 2002;11(suppl 1):i5–i17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Author unknown. Conjoint simulation model. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. February 23, 1993. Bates No. 2045199142/9311. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed September 15, 2000.

- 48.US Dept of Health and Human Services. A model of smoking initiation: cigarette advertising as a shaping force of an adolescent's ideal self-image. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. 1994. Bates No. 2048711844. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed November 28, 2000.

- 49.Ansberry C, Oboyle T, Roberts J. Today's adult young male smoker. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. August 1992. Bates No. 2060127742/7919. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed August 24, 2000.

- 50.R. J. Reynolds. 1985 Segment Description Study. Overview Presentation. 1985. Bates No. 506203246 -3327. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com. Accessed January 28, 2001.

- 51.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Using tobacco industry marketing research to design more effective tobacco control campaigns. JAMA. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Fields TF. Correlation of brand switching with life passages. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. January 19, 1982. Bates No. 501745636 -5637. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com. Accessed December 3, 2000.

- 53.Wakeham H. Dr H. Wakeham R & D presentation to the board of directors (691126). Philip Morris USA. November 26, 1969. Bates No. 1000276678/6690. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed April 29, 2002.

- 54.Yeaman A. Implications of Battelle Hippo I & II and the Griffith Filter. Brown and Williamson Tobacco Company. July 17, 1963. Bates No. 1802.05. Available at: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/html/1802.05/index.html. Accessed October 12, 2001.

- 55.Parrott AC. Nesbitt's Paradox resolved? Stress and arousal modulation during cigarette smoking. Addiction. 1998;93:27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Himmelfarb S. Beyond “X”—a different look at 18–29s. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. November 1992. Bates No. 2045199377–9394. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed September 15, 2000.

- 57.Heironimus J. Impact of workplace restrictions on consumption and incidence. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. January 21, 1992. Bates No. 2045447779–7806. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed December 21, 2000.

- 58.Author unknown. Summary of segmentation among Marlboro smokers. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. No date [content suggests document date is 1984]. Bates No. 506190133–0139. Available at: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/mangini. Accessed November 30, 2000.

- 59.Sepe E, Glantz SA. Bar and club tobacco promotions in the alternative press: targeting young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:75–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Author unknown. Younger adult smoker opportunity. Purpose. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. April 1988. Bates No. 506653159 -3218. Available at: http://www.rjrtdocs.com. Accessed March 11, 2001.

- 61.Heller & Cohen. Proposal program concepts for Kent International. Lorillard Tobacco Company. April 5, 1994. Bates No. 93347305/7326. Available at: http://www.lorillarddocs.com. Accessed October 29, 2001.

- 62.Young & Rubicam. Brand X: a qualitative exploratory among young adult male smokers. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. February 1994. Bates No. 2040174998/5045. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed August 30, 2000.

- 63.Taylor Shain Inc. Proposal for a Boston tactical plan targeted for the young adult segment using the “tunnels of influence” strategic construct. Lorillard Tobacco Company. April 10, 1985. Bates No. 85003058/3074. Available at: http://www.lorillarddocs.com. Accessed October 29, 2001.

- 64.Bruce Eckman Inc. The viability of the Marlboro Man among the 18–24 segment. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. March 1992. Bates No. 2045060177/0203. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed October 13, 2000.

- 65.Brainreserve. Final presentation for Philip Morris USA. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. December 22, 1988. Bates No. 2044328997/9058. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed October 16, 2000.

- 66.Leo Burnett Agency. The young adult woman smoker. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. June 1991. Bates No. 2050900002/0115. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed September 6, 2000.

- 67.Nassar SC. Marlboro vulnerability—idea generation. R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. January 21, 1985. Bates No. 503043738–3746. Available at: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/mangini. Accessed November 30, 2000.

- 68.RIVA Market Research Inc. Final report on eight focus groups with black and white users of Newport, Salem, and Kool Cigarettes on issues related to Newport cigarettes and its advertising campaign. Lorillard Tobacco Company. January 1994. Bates No. 82875399/5507. Available at: http://www.lorillarddocs.com. Accessed May 2001.

- 69.Tindall J. Cigarette market history and interpretation and consumer research. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. February 13, 1992. Bates No. 2057041153/1196. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed July 5, 2001.

- 70.Friedman LR, Lazarsfeld PF, Meyer AS. Motivational conflicts engendered by the on-going discussion about cigarette smoking. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. January 1972. Bates No. 1003291740/1916. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Accessed December 15, 2000.

- 71.Magzamen S, Glantz SA. The new battleground: California's experience with smoke-free bars. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.National Association of Attorneys General. Master settlement agreement. 1998. Available at: http://www.naag.org/tobac/cigmsa.rtf. Accessed February 15, 2001.

- 73.Matthews TJ. Smoking during pregnancy in the 1990s. Natl Vital Stat Rep. August 28, 2001;49(7). [PubMed]

- 74.Ventura SJ, Mosher WD, Curtin SC, Abma JC, Henshaw S. Highlights of trends in pregnancies and pregnancy rates by outcome: estimates for the United States, 1976–96. Natl Vital Stat Rep. December 15, 1999;47(29). [PubMed]

- 75.Chaloupka FJ. Macro-social influences: the effects of prices and tobacco-control policies on the demand for tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(suppl 1):S105–S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Biener L, Aseltine RH Jr, Cohen B, Anderka M. Reactions of adult and teenaged smokers to the Massachusetts tobacco tax. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1389–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Smokefree workplaces substantially reduce smoking: a systematic review. BMJ. In press.

- 78.Chapman S, Borland R, Scollo M, Brownson RC, Dominello A, Woodward S. The impact of smoke-free workplaces on declining cigarette consumption in Australia and the United States. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1018–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Farkas AJ, Gilpin EA, Distefan JM, Pierce JP. The effects of household and workplace smoking restrictions on quitting behaviours. Tob Control. 1999;8:261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Rigotti NA. Cigarette use by college students in smoke-free housing. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pierce JP, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ. Can strategies used by statewide tobacco control programs help smokers make progress in quitting? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:459–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gilpin EA, White MM, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Home smoking restrictions: which smokers have them and how they are associated with smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1:153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Biener L, Cullen D, Di ZX, Hammond SK. Household smoking restrictions and adolescents' exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Prev Med. 1997;26:358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.National Cancer Institute. Health Effects of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke: The Report of the California Environmental Protectional Agency (Smoking and Health Monograph 10). Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute; 1999. NIH publication 88-4645. Available at: http://rex.nci.nih.gov/NCI_MONOGRAPHS/MONO10/MONO10.HTM. Accessed March 15, 2002.

- 85.Goldman LK, Glantz SA. Evaluation of antismoking advertising campaigns [see comments]. JAMA. 1998;279:772–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Association of the California Tobacco Control Program with declines in cigarette consumption and mortality from heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1772–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Controlling tobacco use. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1798–1799. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Healton C. Who's afraid of the truth? Am J Public Health. 2001;91:554–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wakefield M, Chaloupka F. Effectiveness of comprehensive tobacco control programmes in reducing teenage smoking in the USA. Tob Control. 2000;9:177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Institute of Medicine. State Programs Can Reduce Tobacco Use. Washington, DC: National Cancer Policy Board, Institute of Medicine, National Research Council; 2000.

- 91.Lynch BS, Bonnie RJ, Institute of Medicine (US), Committee on Preventing Nicotine Addiction in Children and Youths. Growing up Tobacco Free: Preventing Nicotine Addiction in Children and Youths. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [PubMed]

- 92.Kozlowski LT, Coambs RB, Ferrence RG, Adlaf EM. Preventing smoking and other drug use: let the buyers beware and the interventions be apt. Can J Public Health. 1989;80:452–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Doll R, Peto R. Mortality in relation to smoking: 20 years' observation on male British doctors. BMJ. 1976;2:1525–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]