Abstract

Purpose

To determine the incidence of glaucoma following cataract surgery in children and to identify surgically modifiable risk factors that may influence the development of glaucoma in these eyes.

Methods

All lensectomies performed in patients 18 years old or younger over a 7-year period (1995 through 2001) were identified by conducting a database search. A retrospective chart review was performed for every patient identified. Data extraction included patient’s age at surgery, intraocular lens implantation at cataract extraction, date of glaucoma onset, and length of follow-up. Statistical methods included risk ratio calculations and Kaplan-Meier analyses for the “time to glaucoma” for eyes undergoing lensectomy.

Results

We identified 116 eyes of 79 children in whom lensectomy was performed. The median age at cataract surgery was 178 days (~6 months). Mean follow-up time was 2.7 years. The overall incidence of glaucoma was 11%. Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that eyes operated on at less than 30 days of age were statistically more likely to develop glaucoma than eyes operated on at age 30 days or older (P < .001). For those operated on at less than 30 days of age, the risk ratio was 11.8 for subsequent glaucoma development compared with those operated on at 30 days of age or older. Forty-nine eyes (42%) had primary intraocular lens implantation, and none of these developed glaucoma (P = .001).

Conclusions

Timing of surgery at less than 30 days of age and lack of implantation of an intraocular lens at lensectomy were both associated with an increased risk of subsequent glaucoma. Knowledge of modifiable risk factors is essential to allow ophthalmic surgeons to make cogent decisions regarding the care of children with cataracts.

INTRODUCTION

Early detection and surgical treatment of pediatric cataracts have greatly improved the visual prognosis in children with this congenital and/or developmental condition over the past several decades.1 Despite these advances, the development of subsequent glaucoma remains one of the most frequent serious complications following lensectomy in children, with reported incidence rates varying between 0 and 32% of eyes.2–18 Aphakic glaucoma in infants and children may present early in the postoperative course after lensectomy, or it may present years later. This condition can be difficult to manage, and parents should be counseled about the risk of developing this complication and its consequences.

Reported risk factors for the development of pediatric aphakic glaucoma include ocular morphologic findings such as microphthalmia, persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, small corneal diameter, and type of cataract.9,17 Other risk factors, relating to the surgical procedure itself, have also been reported and include the timing of surgery (patient’s age at surgery)7,8,11,14 and lack of implantation of an intraocular lens.19–21

Whereas the occurrence of glaucoma following cataract extraction has long been recognized,22 the study of factors that are modifiable by the ophthalmic surgeon deserves further evaluation. Knowledge of “best practices” has the potential to result in improved visual outcomes for these children. We undertook this study to determine the overall incidence of glaucoma following cataract surgery in a cohort of children, and to identify and quantify surgeon-modifiable risk factors that might influence the development of glaucoma in these eyes.

METHODS

SUBJECTS

Approval of the Fairview University Medical Center Institutional Review Board was obtained before initiation of the study. All cataract extractions performed in patients 18 years old or younger over a 7-year period from January 1995 through December 2001 by surgeons in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota were identified by database search for all procedures with CPT codes 66840, 66850, 66983, 66984, and 66940. A chart review was performed for every case identified. Eyes with traumatic cataract, preexisting glaucoma, and other serious ocular malformations, including anterior segment dysgenesis, Lowe syndrome, and persistent fetal vasculature, were excluded.

Data extraction included patient age at surgery, intraocular lens implantation at cataract extraction, date of glaucoma onset, and length of follow-up. We designated cases as having glaucoma on the basis of the attending ophthalmologist’s recorded decision to start long-term glaucoma medications, perform glaucoma surgery, or refer to a glaucoma specialist.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Lensectomies were performed through a standard limbal or pars plana incision. Posterior capsulotomies and anterior vitrectomies were performed with automated vitrectomy instrumentation. Forty-nine eyes (42%) had intraocular lens implantation at the time of lensectomy. Topical corticosteroids were routinely used postoperatively. For those without intraocular lens implantation, contact lens fitting was usually performed 1 week postoperatively.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to evaluate the time to glaucoma for all eyes in the study. The analysis was also stratified by the patient’s age at surgery (<30 days, ≥30 days) and intraocular lens implantation. These subgroups were compared using the log-rank test, and a P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Risk ratios were calculated for the following variables: age at surgery, gender, and intraocular lens implantation at the time of lensectomy. Only patients followed for more than 12 months were included for calculation of risk ratios.

RESULTS

The data from 116 lensectomies in 79 patients were included in this study. All surgeries were performed for congenital or developmental cataracts. Thirty-six patients (46%) were male, and the median age at cataract surgery was 178 days (~6 months). Mean follow-up time was 2.7 years. Forty-nine eyes (42%) underwent primary intraocular lens implantation. Thirteen eyes developed glaucoma, for an overall incidence of glaucoma of 11%.

Table 1 shows the clinical features of each of the 13 eyes that developed subsequent glaucoma. Ten of the 13 eyes with glaucoma underwent lensectomy at less than 30 days of age. None had intraocular lens implantation at initial lensectomy. Eight of 13 eyes required at least one glaucoma surgery, and of those, three required three glaucoma surgeries. (Glaucoma surgeries included trabeculotomies, goniotomies, trabeculectomies, and shunt procedures.) The final recorded visual acuity in eyes that developed subsequent glaucoma ranged from 20/20 to no light perception (due to enucleation). Two eyes had final visual acuities better than 20/60, two eyes had visual acuities between 20/60 and 20/180, five eyes had visual acuities between 20/200 and 20/3000, three eyes did not have vision recorded in the chart, and one eye was eventually enucleated.

TABLE 1.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF EYES THAT DEVELOPED SUBSEQUENT GLAUCOMA

| EYE | OD or OS | UNILATERAL OR BILATERAL CATARACT | TIMING OF LENSECTOMY (PATIENT’S AGE IN DAYS) | IOL | GLAUCOMA ONSET (DAYS AFTER LENSECTOMY) | GLAUCOMA SURGICAL TREATMENT (NO.) | MOST RECENT VISUAL ACUITY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | OS | B | 9 | N | 26 | Y (2) | 20/710 (OU) |

| 2 | OD | U | 17 | N | 82 | Y (3) | NA |

| 3 | OS | U | 16 | N | 254 | N | Enucleated |

| 4 | OD | B | 18 | N | 1,871 | Y (1) | 20/20 |

| 5 | OD | U | 19 | N | 90 | Y (2) | NA |

| 6 | OD | U | 20 | N | 148 | Y (1) | 20/200 |

| 7 | OD | U | 21 | N | 50 | N | NA (phthisis) |

| 8 | OD | U | 23 | N | 1,942 | N | 20/25 |

| 9 | OD | B | 26 | N | 56 | N | 20/360 (OU) |

| 10* | OD | B | 27 | N | 8 | Y (3) | 20/710 (OU) |

| 11 | OS | U | 48 | N | 62 | Y (3) | 20/3000 |

| 12 | OS | U | 213 | N | 183 | Y (1) | 20/125 |

| 13 | OD | U | 503 | N | 1,308 | N | 20/125 |

B = bilateral

IOL = intraocular lens implantation at the time of lensectomy

N = no

NA = not available

OD = right eye

OS = left eye

U = unilateral

Y = yes

Eyes 1 and 10 belong to same patient.

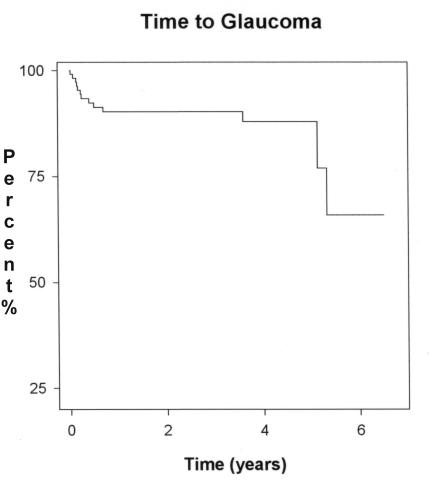

In our series, the earliest diagnosis of glaucoma was 8 days after lensectomy (Table 1, eye 10); the latest diagnosis was made 1,942 days after surgery in the middle of the fifth year (Table 1, eye 8). The mean time between cataract surgery and the detection of glaucoma was 468 days (~1 year, 3 months). The Kaplan-Meier curve of time to glaucoma for the overall pediatric lensectomy cohort is shown in Figure 1. By 5 years after lensectomy, approximately 70% of the cohort remained “glaucoma-free.”

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of glaucoma incidence of overall pediatric lensectomy cohort (n = 116 eyes).

TIMING OF LENSECTOMY

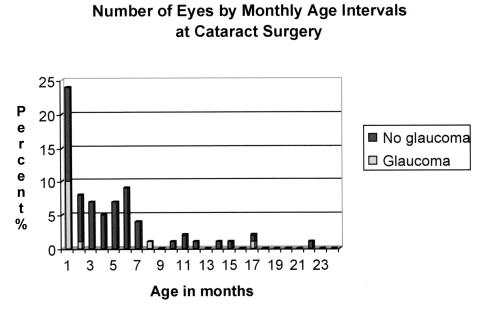

The timing of lensectomy in our series ranged from 4 days to 17.5 years of age. The median age at surgery was 21 days for those that developed glaucoma and 208 days (~7 months) for those that did not develop glaucoma. All eyes that subsequently developed glaucoma were operated on within the first 24 months of life. The number of eyes undergoing lensectomy, by month, for the first 2 years of life is shown in Figure 2. Of the eyes operated on during the first month of life, 42% (10 of 24) developed glaucoma.

FIGURE 2.

Number of eyes undergoing lensectomy, by month, for the first 24 months of life. All 13 eyes that subsequently developed glaucoma were operated on within this time period. Of the 24 eyes operated on within the first month of life, 10 (42%) subsequently developed glaucoma.

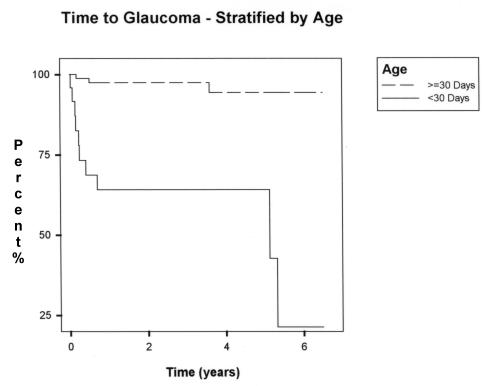

Risk factor analysis is shown in Table 2. The total number of eyes with at least 1 year of follow-up was 86. Eyes that underwent lensectomy when the infant was less than 30 days of age were 11.8 times more likely to develop glaucoma than eyes that underwent surgery when infants were more than 1 month of age (P < .001). The Kaplan-Meier analysis of glaucoma incidence stratified by timing of surgery, shown in Figure 3, also showed a statistically significant difference in events (P < .001). By 5 years after surgery, approximately one fourth of eyes operated on within the first month of life were “glaucoma-free.”

TABLE 2.

RISK FACTOR ANALYSIS FOR GLAUCOMA DEVELOPMENT (N = 86)

| RISK FACTOR | CASES OF GLAUCOMA (N = 13) | CASES WITHOUT GLAUCOMA (N = 73) | RISK RATIO | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOL implantation | 0 (0%) | 34 (46.6%) | Undefined | .001 |

| Age at surgery (<30 days) | 10 (76.9%) | 9 (12.3%) | 11.8 | <.001 |

| Gender | 7 (53.8%) | 34 (46.6%) | 1.3 | .629 |

IOL = intraocular lens.

P value was determined from the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of glaucoma incidence stratified by age at surgery (P value of the log-rank test: <.001).

PRIMARY INTRAOCULAR LENS IMPLANTATION

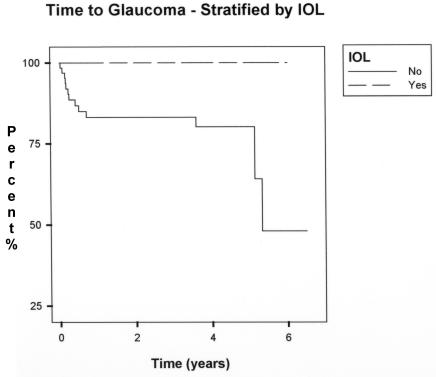

Intraocular lens implantation at the time of lensectomy was performed in 49 eyes (42%). The median age at surgery for the pseudophakic group was 4.53 years, with a range of 37 days to 17.5 years. No cases of lensectomy with primary intraocular lens implantation developed glaucoma.

Sixty-seven eyes (58%) had no intraocular lens implanted at the time of lensectomy. The median age at surgery for the aphakic group was 88 days (~3 months), with a range of 4 days to 6.1 years.

Risk factor analysis for primary intraocular lens implantation is shown in Table 2. In no cases of lensectomy with primary intraocular lens implantation did glaucoma develop. Because of this, the risk ratio was undefined; however, intraocular lens implantation appeared to have a protective effect (P = .001). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a statistically significant difference in glaucoma incidence by 5 years postoperatively (P = .002), as shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of glaucoma incidence stratified by intraocular lens implantation at the time of lensectomy (P value of the log-rank test: .002).

RELATIVE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE TREATMENT FACTORS

To determine which of the two factors, either timing of surgery or implantation of an intraocular lens, had more impact on the occurrence of glaucoma, we separated the eyes into subgroups defined by these two variables. (A factorial analysis could not be performed because no cases of glaucoma occurred in pseudophakic eyes.) Table 3 shows the subgroup analysis of the incidence of glaucoma in aphakic eyes that underwent surgery at 30 days of age or older (9.1%) and in those that had surgery at less than 30 days of age (39.1%). The rate of glaucoma in the subgroups was compared using the chi-square test and was statistically significantly different between the subgroups (P = .016). Both treatment variables appeared to have a substantial effect, but timing of surgery seemed to have a larger impact on glaucoma rates.

TABLE 3.

SUBGROUP ANALYSIS FOR GLAUCOMA DEVELOPMENT: IOL IMPLANTATION VERSUS TIMING OF SURGERY IN EYES THAT DEVELOPED GLAUCOMA

| SUBGROUP | TREATMENT VARIABLES | GLAUCOMA INCIDENCE |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | IOL and age ≥30 days | 0/49 (0%) |

| 2* | No IOL and age ≥30 days | 4/44 (9.1%) |

| 3* | No IOL and age <30 days | 9/23 (39.1%) |

IOL = intraocular lens.

The pairwise comparison between subgroups 2 and 3 was statistically significant (P value of the chi-square: .016).

DISCUSSION

The current study is a retrospective analysis of childhood cataract surgery performed at our institution over a 6-year period. It is limited by variable follow-up of patients and incomplete data available in the medical records. Multiple surgeons performing somewhat different lensectomy techniques may also compromise the data. Microphthalmia, microcornea, extent of pupillary dilation at the time of surgery,10 type of cataract,9 amount of residual lens tissue, and gonioscopic findings,23 although previously reported to be risk factors for glaucoma, were inconsistently documented in our medical records and thus were not included in our data collection. Despite these limitations, our series represents one of the only studies to focus on surgeon-modifiable variables.

We analyzed our data to determine whether two treatment variables determined by the ophthalmologist’s treatment plan—timing of surgery and intraocular lens implantation—showed statistical significance for the development of glaucoma. Both of these modifiable factors showed significant impact on glaucoma incidence.

The relative risk ratio for development of glaucoma in children undergoing surgery before the age of 1 month was 11.8. This supports previously published reports showing a significantly higher rate of glaucoma in patients undergoing surgery at younger ages. The series reported by Keech and coworkers in 19897 showed an overall glaucoma incidence of 11% and age less than 8 weeks to be a significant risk factor. Magnusson and colleagues8 reported a Swedish cohort with a 12% glaucoma incidence and age at lensectomy of less than 10 days to be a significant risk factor. Early surgery was also shown to be a significant risk factor in a series reported by Vishwanath and associates11 from the Great Ormond Street Hospital in London, leading them to pose the question, “Should we delay congenital cataract surgery until four weeks old?” In contrast, Watts and coworkers,14 using classification and regression trees analysis, found a higher incidence of glaucoma among infants operated on between 13.5 days and 43 days of life than among those operated on under 14 days of age. They concluded that the first 2 weeks of life were the most favorable time to perform lensectomy. In our series, seven eyes were operated on during the first 2 weeks of life, one of which developed glaucoma, so our data do not confirm a “safe window” with respect to glaucoma development within the first 2 weeks of life. Of the eyes that developed subsequent glaucoma, however, 9 of 13 (69%) were operated on between 16 and 27 days of life Other studies reporting no association with age at surgery included fewer patients who underwent early surgery or did not analyze data regarding timing of surgery.5,9,24

Timing of surgery can have a major impact on long-term visual prognosis in eyes with congenital cataracts. Surgery performed after 6 to 8 weeks of age may result in deprivation of visual stimuli and less favorable visual outcomes.25–27 It is now generally accepted practice that lensectomy in the pediatric population be performed as early as possible to maximize visual functioning and minimize the effects of amblyopia and nystagmus. With the mounting evidence that timing the lensectomy within the first few weeks of life may lead to a higher incidence of glaucoma, perhaps pediatric ophthalmologists should consider delaying surgery until 30 days of life. A randomized, prospective study may be optimal to reduce the inherent biases of retrospective analyses and, may help to determine if it is the timing of the surgery per se that leads to the increased rate of glaucoma, or if the increased rate of glaucoma is due to intrinsic factors associated with eyes that are brought to surgery earlier.

Our study also demonstrated that primary intraocular lens implantation during lensectomy may be associated with a significantly decreased risk of subsequent glaucoma development. Asrani and colleagues28 recently reported a retrospective analysis of two large databases from multiple centers in the United States that suggested a reduced incidence of glaucoma in the primary pseudophakic eyes (0.3%), compared with those that were left aphakic (11.3%). In contrast, Lambert and coworkers20 compared outcomes in children with and without primary intraocular lens implantation in lensectomies performed within the first 6 months of life. They found that the intraocular lens group had higher rates of complications requiring reoperation, including two of 12 that required glaucoma surgery. Our study lends more evidence to confirm Asrani and coworkers’ suggestions that primary intraocular lens implantation may be protective for the development of glaucoma.

Possible biases that may confound the findings of our study include detection bias and selection bias. Infants are more likely to be operated on earlier when their cataract is detected and referred earlier, such as when there is a family history of congenital cataract. Are we preferentially selecting infants with worse disease or those that may have a known familial genetic predisposition for the group that has a higher incidence of glaucoma? Do infants who are diagnosed earlier have more involvement of a single disease process that involves the trabecular outflow channels and hence the higher rate of glaucoma? Although it is tempting to propose a single disease entity that would account for both congenital cataract and glaucoma, other investigators have felt that the glaucoma appears to develop only if, and after, lensectomy is performed.29,30 Our study excluded eyes in which a diagnosis of glaucoma had been made prior to the lensectomy and thus does not shed new light on this question.

The pathogenesis of pediatric aphakic glaucoma is not well understood. In very young, small eyes, with a smaller pupil, perhaps the surgery is more difficult and may lead to more retained lens material and hence greater postoperative inflammation. The role of postoperative use of corticosteroids should also be considered.11 The finding that aphakic glaucoma is detected, in some cases, years after lensectomy and discontinuation of corticosteroids, with the intervening period documented by normal intraocular pressures and no uveitis, would make this cause unlikely for most cases.

Perhaps the cause is some aspect of the actual surgery, in combination with an early period of sensitivity that lasts about 30 days. It is possible that a structural change in the trabecular meshwork, or its supporting beams, may occur during the surgery or afterwards, when the lens is removed. The lack of structural rigidity in very young eyes may lead to either collapse or stretching of the trabecular meshwork during surgery, causing permanent physiologic damage or disrupted maturation of the meshwork. The role of the stretch of the zonular fibers, and hence the ciliary processes, when an intraocular lens is inserted, and the lack thereof in aphakic eyes, should also be considered. The role of vitreous chemical components has also been suggested.19

In conclusion, we found that lensectomy performed during the first 30 days of life was associated with a higher risk of subsequent glaucoma than surgery performed later. In our series, the implantation of an intraocular lens at the time of lensectomy was associated with a lower rate of subsequent glaucoma. The independent contribution of each of these treatment variables could not be determined in this study, but both factors appear to exert an effect. Although it may be tempting to delay cataract surgery until after 30 days of age and to consider primarily implanting an intraocular lens in very young infants, prospective randomized studies will be needed to corroborate or refute these findings and, may help to elucidate mechanisms of the pathogenesis of this challenging disease. Knowledge of modifiable risk factors is essential to allow pediatric ophthalmic surgeons to make cogent decisions regarding the care of children with cataracts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bruce Lindgren, Director of the Biostatistics Consulting Lab, Division of Biostatistics at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, for his invaluable biostatistics advice.

Footnotes

This project was supported in part by an unrestricted grant to the University of Minnesota, Department of Ophthalmology, from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc, New York, New York.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biglan A. Outcome of treatment for bilateral congenital cataracts. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1992;90:194–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crouch ER, Crouch ER, Jr, Pressman SH. Prospective analysis of pediatric pseudophakia: myopic shift and postoperative outcomes. J AAPOS. 2002;6:277–282. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2002.126492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pressman SH, Crouch ER. Pediatric aphakic glaucoma. Ann Ophthalmol. 1983;5:568–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francois J. Glaucoma and uveitis after congenital cataract surgery. Ann Ophthalmol. 1971;3:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chrousos GA, Parks MM, O’Neill JF. Incidence of chronic glaucoma, retinal detachment and secondary membrane surgery in pediatric aphakic patients. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1238–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Keefe MO, Mulvihill A, Yeoh PL. Visual outcome and complications of bilateral intraocular lens implantation in children. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:1758–1764. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00561-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keech RV, Tongue AC, Scott WE. Complications after surgery for congenital and infantile cataracts. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108:136–141. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magnusson G, Abrahamsson M, Sjostrand J. Glaucoma following congenital cataract surgery: an 18-year longitudinal follow-up. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:65–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078001065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parks MM, Johnson DA, Reed GW. Long-term visual results and complications in children with aphakia: a function of cataract type. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:826–841. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mills MD, Robb RM. Glaucoma following childhood cataract surgery. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1994;31:355–360. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19941101-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vishwanath M, Cheong-Leen R, Russell-Eggitt I, et al. Is early surgery for congenital cataract a risk factor for glaucoma? Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:905–910. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.040378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robb RM, Peterson RA. Outcome of treatment for bilateral congenital cataracts. Ophthalmic Surg. 1992;23:650–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen TC, Bhatia LS, Walton DS. Complications of pediatric lensectomy in 193 eyes. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2005;36:6–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watts P, Abdolell M, Levin AV. Complications in infants undergoing surgery for congenital cataract in the first 12 weeks of life: Is early surgery better? J AAPOS. 2003;7:81–85. doi: 10.1016/mpa.2003.S1091853102420095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon JW, Mehta N, Simmons ST, et al. Glaucoma after pediatric lensectomy/vitrectomy. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:670–674. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyahara S, Amino K, Tanihara H. Glaucoma secondary to pars plana lensectomy for congenital cataract. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:176–179. doi: 10.1007/s00417-001-0419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egbert JE, Wright MM, Dahlhauser KF, et al. A prospective study of ocular hypertension and glaucoma after pediatric cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1098–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30906-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson CP, Keech RV. Prevalence of glaucoma after surgery for PHPV and infantile cataracts. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1996;33:14–17. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19960101-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asrani SG, Wilensky JT. Glaucoma after congenital cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:863–867. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30942-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert SR, Buckley EG, Plager DA, et al. Unilateral intraocular lens implantation during the first six months of life. J AAPOS. 1999;3:344–349. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(99)70043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plager DA, Yang S, Neely D, et al. Complications in the first year following cataract surgery with and without IOL in infants and children. J AAPOS. 2002;6:9–14. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2002.121169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandler PA. Surgery of the lens in infancy and childhood. Arch Ophthalmol. 1951;45:125–138. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1951.01700010130001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walton DS. Pediatric aphakic glaucoma: a study of 65 patients. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1995;93:403–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phelps CD, Arafat NI. Open-angle glaucoma following surgery for congenital cataracts. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:1985–1987. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450110079005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elston JS, Timms C. Clinical evidence for the onset of the sensitive period in infancy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:327–328. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.6.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birch EE, Stager DR. Prevalence of good visual acuity following surgery for congenital unilateral cataract. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:40–43. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130046025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellemberg D, Lewis TL, Mauer D, et al. Spatial and temporal vision in patients treated for bilateral congenital cataracts. Vis Res. 1999;39:3480–3489. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asrani S, Freedman S, Hasselblad V, et al. Does primary intraocular lens implantation prevent “aphakic” glaucoma in children? J AAPOS. 2000;4:33–39. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(00)90009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phelps CD, Arafat NI. Open-angle glaucoma following surgery for congenital cataracts. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:1985–1987. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450110079005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mori M, Keech RV, Scott WE. Glaucoma and ocular hypertension in pediatric patients with cataracts. J AAPOS. 1997;1:98–101. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(97)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]