Abstract

Purpose

Choroidal and retinal biopsies are often the investigation of last resort in evaluating patients with uveitis, because of the possible morbidity of the procedure. The most common indication is atypical uveitis, in which a diagnosis of malignancy or infection may be suspected. Here, we describe our experience at the Casey Eye Institute.

Methods

This was a retrospective case series from January 2000 through October 2004. Cases labeled as “retinal or choroidal biopsy” were drawn from the pathology database at the Casey Eye Institute, and the pathology and clinic charts were reviewed. In all cases, the retinal and choroidal biopsies were obtained via an internal approach with a three-port pars plana vitrectomy.

Results

Eight cases of atypical uveitis were found for which choroidal biopsies were performed. Five patients had had previous vitrectomies, in which examination of the vitreal sample had been inconclusive. Five patients had a definitive diagnosis after the biopsy and a good response to tailored therapy. In one case, diagnosis was made after biopsy, but clinical improvement was minimal despite appropriate treatment. One case had an inconclusive biopsy that enabled the exclusion of malignancy and infection with good response to immune suppression. In another case, choroidal biopsy was inconclusive and the eventual diagnosis was made only after enucleation.

Conclusion

Retinal and choroidal biopsies can be extremely useful in the diagnosis and further management of atypical, aggressive presentations of uveitis. In this small series, risk of complications was low. However, in patients with an inconclusive biopsy, an additional biopsy or enucleation should be considered in cases that progress or behave atypically on treatment based on the initial biopsy findings.

INTRODUCTION

Choroidal and retinal biopsies are often the investigation of last resort in evaluating patients with uveitis, because of the possible morbidity of such procedures. The most common indication for these biopsies is atypical uveitis, when a diagnosis of malignancy or infection may be suspected. In these situations, a definitive diagnosis is required prior to initiating treatment for presumed autoimmune noninfectious uveitis, because the consequences of immunosuppression in cases of infection or malignancy could be disastrous.

Previous case studies1–3 and, more recently, case series4–6 have illustrated the potential role of chorioretinal biopsies obtained via an internal approach. Here, we describe our experience with eight cases over a 4-year period at the Casey Eye Institute.

METHODS

Cases were obtained by a retrospective review of the Christensen Eye Pathology database at the Casey Eye Institute from January 2000 through October 2004. Cases labeled as “retinal or choroidal biopsy” were identified, and the corresponding case charts from the Casey Eye Institute were reviewed. Oregon Health Sciences University Institutional Review Board permission was granted for the conduct of this study.

In all cases, the retinal and choroidal biopsy specimens were obtained via an internal approach with a three-port pars plana vitrectomy. In all cases, a sample of undiluted vitreous was collected for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the vitreal washings from the rest of the operation used for cytologic and immunologic analysis. After a core vitrectomy and peripheral trim, the area for biopsy was selected, typically at the border of an active edge of the inflammatory mass in the retina or choroid. After the intraocular pressure was raised to 90 mm Hg, endodiathermy was used to necrose the retina, retinal pigment epithelium, and choroid down to sclera and thereby delineate the area for biopsy. The isolated tissue was then removed with vertical and horizontal scissors. Next, the superotemporal sclerostomy was enlarged to enable the removal of the biopsy specimen from the eye. Once hemostasis was achieved with further diathermy, the intraocular pressure was gradually lowered. Endolaser was then used to secure the edges of the retinotomy, and an air-fluid exchange was performed prior to the closure of wounds.

All retinal and choroidal specimens were fixed in buffered formalin for light microscopy and immunohistochemical evaluation. In three cases, a separate specimen was also sent fresh for immediate flow cytometry. In all cases, a dry vitreous tap was performed at the beginning of the procedure and was sent with the vitreal washings for PCR testing for Herpesviridae (Proctor Laboratory, University of California, San Francisco) and standard microbial and fungal microscopy and culture. In cases where a malignant etiology was strongly suspected, samples were also sent for immunophenotyping and gene rearrangement studies. Other investigations were ordered as clinically appropriate.

RESULTS

Eight cases (six female, two male) of atypical uveitis were identified for which choroidal biopsies were performed (Table 1). The average age of the patients at presentation was 55 years (range, 16 to 73 years), and mean duration of follow-up was 40.5 months (range, 10 months to 7 years). Visual acuity prior to the biopsy was generally poor; four patients had acuity of count fingers at 1 foot or worse. The other four patients had visual acuities ranging from 20/25 to 20/100 preoperatively. Six to 12 months after biopsy, visual acuity remained unchanged in four patients, improved 2 Snellen lines in one, and worsened in three by 1 to 3 Snellen lines (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

DEMOGRAPHICS, SYMPTOMS, AND SIGNS OF EIGHT PATIENTS WITH ATYPICAL PRESENTATIONS OF UVEITIS PRIOR TO PROCEEDING TO A RETINAL OR CHOROIDAL BIOPSY

| PATIENT | AGE AT PRESENTATION (YR) | GENDER | PAST MEDICAL HISTORY | SYMPTOMS | SIGNS | DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 68 | F | Unremarkable | Progressive loss of vision OD | Retinal pallor and intraretinal hemorrhage at the posterior pole, 2+ AC and vitreal cell | Intraocular lymphoma, viral retinitis |

| B | 16 | F | Painless loss of vision OS with retinitis and fibrosis; stabilized after short course oral prednisone treatment | Floaters and painless loss of vision OD 6 years later | Panuveitis with 2+ AC and vitreal cell, retinitis, and intraretinal hemorrhage | ARN, subretinal fibrosis, uveitis syndrome |

| C | 28 | F | Unremarkable | Rapid bilateral loss of vision with ocular pain and injection; no response to prednisone, MTX, and CSA | Bilateral panuveitis with 1+ AC cell and dense vitritis precluding view of fundus | ? Sarcoidosis |

| D | 48 | F | Unremarkable | Fluctuating visual loss OD | Remitting/relapsing creamy choroidal infiltrates, no AC cell, trace vitreal cell | ? AMPPE

? Lymphoma |

| E | 83 | M | Testicular lymphoma diagnosed and treated 5 years prior, in remission | Sudden onset painless loss of vision OS | 1 to 2+ AC cell with widespread hemorrhagic retinitis | ARN, CMV, lymphoma |

| F | 66 | F | Cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma, systemic chemotherapy; in remission for 2 years before ocular presentation | Gradual painless loss of vision over 2 weeks | 3+ vitreal cell and haze, extensive inferior creamy, placoid, subretinal lesions | Intraocular lymphoma |

| G | 61 | F | Stage 4 large B-cell lymphoma, systemic chemotherapy, in full remission 1 year prior to developing ocular symptoms | Blurred vision OS | Subretinal infiltrates OS, no cell | Intraocular lymphoma |

| H | 73 | M | Unremarkable | Bilateral floaters and blurred vision | No AC or vitreal cells, yellow subretinal lesions at posterior pole; resolved completely with oral prednisone before recurring | ? Intraocular lymphoma or unusual vitelliform dystrophy |

AC = anterior chamber; AMPPE = acute multifocal posterior placoid pigment; ARN = acute retinal necrosis; CMV = cytomegalovirus; CSA = cyclosporin A; MTX = methotrexate.

TABLE 2.

OUTCOMES BEFORE AND AFTER CHORIORETINAL BIOPSY IN EIGHT PATIENTS WITH ATYPICAL PRESENTATIONS OF UVEITIS

| PATIENT | VA (PREBIOPSY) | DURATION OF FIRST SYMPTOMS BEFORE BIOPSY | DIAGNOSTIC VITRECTOMY RESULT (IF DONE PRIOR TO RETINAL BIOPSY) | RETINAL/CHOROIDAL BIOPSY RESULT | ENUCLEATION RESULT | DIAGNOSIS | FINAL VA | DURATION OF FOLLOW-UP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | LP | 2 weeks | Negative cytology and flow cytometry; viral PCR and microbial cultures negative | Necrotic retina with destruction of normal retina, atypical lymphocytic infiltrate | N/A | Intraocular lymphoma; CNS lymphoma, diagnosed soon after | LP | 5 years |

| B | NLP OS

20/30 OD |

7 years | N/A | OS: Metaplastic changes in choroid and RPE with bone, fibrosis, and mild lymphocytic infiltrate. No retinal inflammatory infiltrate. Viral PCR and staining negative | N/A | Uveitis and subretinal fibrosis | NLP OS

20/20 OD |

9 years |

| C | NLP OD

LP OS |

56 weeks | N/A | OD: Granulomatous inflammation of the choroids and retina; staining for AFB, fungi negative, PCR for viruses and Toxoplasma negative | N/A | Sarcoid | NLP OU | 7 years |

| D | 20/25 | 94 weeks | Negative cytology and flow cytometry for malignancy | Dense choroidal infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Immunophenotying: Monoclonal B-cell infiltrate consistent with low-grade B-cell lymphoma of MALT type with plasmacytic differentiation | N/A | Intraocular lymphoma | 20/70 | 25 months |

| E | 20/100 OS

20/30 OD |

20 weeks | Negative cytology and flow cytometry for malignancy; negative viral PCR | OS: Chronic inflammation with mild necrosis of retina with minimal inflammatory cell infiltrate, moderate lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrate in choroid. Flow cytometry negative for malignancy | Diffuse infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes in the sub-RPE space. Flow and immunophenotyping positive | Diffuse large B-cell intraocular lymphoma | 20/50 OD

Prosthesis OS |

15 months |

| F | CF | 4 weeks | Negative cytology and flow cytometry for malignancy | Sub-RPE atypical lymphocytes positive CD20+ and Ki-67 immunohistology stains | N/A | Intraocular lymphoma | CF | 14 months |

| G | 20/50 | 1 week | N/A | Choroidal infiltrate of large atypical cells, cell marker studies confirm relapse of large cell lymphoma (CD 20 and CD 45 positive) | N/A | Intraocular lymphoma | 20/60 | 10 months |

| H | 20/80 | 18 weeks | Negative cytology and flow cytometry for malignancy | Choroidal lymphocytic infiltrate containing large cells with large atypical nuclei. | N/A | Intraocular lymphoma | 20/40–2 | 44 months |

AFB = acid-fast bacteria; CF = count fingers; CNS = central nervous system; LP = light perception; MALT = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; N/A = not applicable; NLP = no light perception; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; RPE = retinal pigment epithelium; VA = visual acuity.

Prior to the biopsy, symptoms had been present for an average of 66 weeks (range, 1 week to 7 years). Seven patients had received oral, topical, or periocular corticosteroids prior to surgery, and one (patient C) had been treated with other forms of immunosuppression (methotrexate plus cyclosporin). Two patients had been treated with systemic antiviral medication (oral valacyclovir) (patients B and E), and another patient had been treated with intravitreal foscarnet (patient A).

Of the eight biopsies, five had prior vitrectomies, with an inconclusive examination of the vitreal sample. Five patients had a definitive diagnosis after the biopsy. This enabled more appropriate and targeted therapy, with good results. Another patient also had a definitive diagnosis based on biopsy results, but had minimal clinical and visual improvement despite appropriate treatment. In one case, results of choroidal biopsy were inconclusive and diagnosis was made only after enucleation. In the final case, biopsy was also inconclusive but was nonetheless sufficient to exclude malignancy and infection, thus enabling the continuation of aggressive immunosuppression with good results (Table 2).

One patient (patient H) initially presented with unusual choroidal infiltrates that had been present for several months prior to developing intraocular inflammation (patient H). The seven other patients presented with panuveitis associated with atypical retinal or choroidal lesions. Three of these patients were initially thought to have a viral retinitis (eg, acute retinal necrosis, cytomegalovirus retinitis) and therefore received prolonged systemic antiviral treatment or intravitreal foscarnet, or both. In one of these cases (patient B), biopsy revealed areas of fibrosis and no retinitis and the patient later did well with immunosuppression. In another of these cases, biopsy revealed diffuse B-cell lymphoma and the patient was therefore treated with chemotherapy and intravitreal methotrexate. In the third case, biopsy showed areas of retinal necrosis but no evidence of lymphoma (Figure 1) . Antiviral treatment was therefore continued, with no improvement, and a diagnosis of lymphoma was eventually made after a diagnostic enucleation.

FIGURE 1A.

Color fundus photograph of the left eye of patient E, an 83-year-old man who presented with sudden, painless loss of vision in the left eye associated with 1 to 2+ anterior chamber cell and widespread hemorrhagic retinitis, as seen here.

FIGURE 1B.

Color fundus photograph of the right eye of patient E, an 83-year-old man who presented with sudden painless loss of vision in the left eye due to hemorrhagic retinitis that failed to respond to antiviral treatment. This picture was taken subsequent to the choroidal biopsy of the left eye.

FIGURE 1C.

Color fundus photograph of the right eye of patient E, an 83-year-old man with progressive hemorrhagic retinitis of the left eye that failed to respond to antiviral treatment. This picture was taken prior to a diagnostic enucleation of the left eye and shows retinal findings in the right eye similar to those that were seen initially in the left eye.

Three patients had a history of systemic lymphoma that predated the onset of uveitis and choroidal lesions by several years. In all of these cases, the systemic lymphoma was considered to be in remission at the time of the ocular presentations, but lymphoma was eventually found to be the cause of the atypical uveitis. In all eight cases, the biopsy site chosen was the leading, active edge of inflammation and the posterior pole was spared. No intraoperative or postoperative complications (eg, retinal detachment) were seen in any of the eight cases.

CASE STUDIES

PATIENT C

A previously healthy woman first presented in 1997 at the age of 28 with a history of bilateral severe panuveitis. Symptoms consisted of bilateral ocular injection, severe photophobia, and progressively decreasing vision despite frequent topical prednisolone acetate (Allergan, Irvine, California) eye drops. Systems review failed to elicit any symptoms consistent with an underlying systemic illness.

Examination revealed a best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of hand movements in the right eye and count fingers at 10 cm in the left. Intraocular pressures were 8 and 9 mm Hg, respectively. One plus cell and two plus flare were noted in both anterior segments with extensive posterior synechia. Bilateral nuclear (2+) and posterior subcapsular (2 to 3+) cataract was noted. Because of the nearly secluded pupils, fundus examination of both eyes was significantly limited, although a hazy view on the left revealed vitreous haze, optic nerve swelling, scattered areas of retinal whitening, subretinal infiltrates, and multiple peripheral chorioretinal scars.

Investigations included a chest x-ray, complete blood cell count, inflammatory markers, complete metabolic panel, and syphilis serology, all of which were normal. Further management consisted of oral prednisone, 40 mg per day, plus cyclosporine, 200 mg twice a day, and methotrexate, 17.5 mg per week.

When the intraocular inflammatory disease remained refractory to triple immunosuppression, oral famciclovir (500 mg three times a day) was added because of the presence of presumed retinitis, but this also failed to have effect. Owing to the severe and refractory nature of the inflammation and the atypical and poorly visualized fundus findings, it was decided to proceed to a lensectomy, vitrectomy, and choroidal biopsy in the right eye 4 months after starting immunosuppression. Intraoperative findings included a dense fibrinous membrane covering the posterior pole associated with peripheral chorioretinal scars and areas of subretinal fibrosis. No evidence of active retinitis was seen. Vitreal samples were sent for viral and bacterial PCR and culture (including mycobacteria), and the chorioretinal biopsy specimen was sent for histology and immunostaining.

Histologic examination revealed marked noncaseating granulomatous inflammation of the choroid and, to a lesser extent, retina, which was consistent with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Figure 2). The famciclovir was therefore discontinued, and the patient’s immunosuppression was augmented with monthly intravenous pulse methylprednisolone and periocular triamcinolone injections. Despite this, the patient’s inflammation and retinitis continued to progress, resulting in eventual bilateral phthisis and no perception of light in either eye 2 years later. A computed tomographic scan of the chest performed during this time revealed mild adenopathy and interstitial lung disease, thereby confirming the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

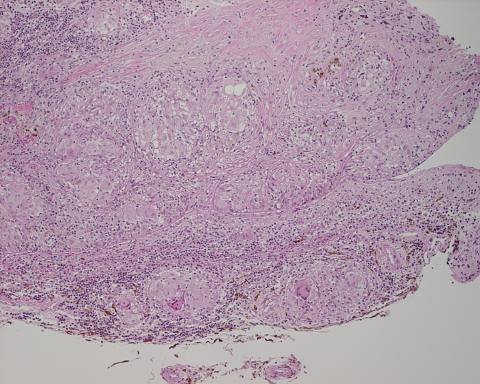

FIGURE 2.

Histologic section of the choroidal biopsy from patient C, a 28-year-old woman who presented with bilateral severe panuveitis that progressed despite aggressive immunosuppression. Biopsy revealed areas of noncaseating, granulomatous inflammation (hematoxylineosin, original magnification ×20).

PATIENT D

A previously healthy 48-year-old woman first presented in 2003 with fluctuating visual loss in the right eye. Examination at the time revealed a BCVA of 20/50 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. Further examination revealed no anterior chamber or vitreal cell. Fundus examination revealed multiple subretinal creamy lesions inferior to the optic disc and macula. Examination of the left eye showed no abnormalities. Review of systems and routine laboratory investigations, including a chest x-ray, were normal.

A provisional diagnosis of acute multifocal posterior placoid pigment epitheliopathy was made and appeared to be correct when the lesions faded and were replaced with pigmentary changes over a period of 4 weeks. BCVA also improved to 20/20. Two months later, although the patient remained asymptomatic, the subretinal lesions were noted to recur with trace vitreous cell and areas of subretinal fluid (Figure 3). These lesions were then noted to completely resolve with pigmentary changes 8 weeks later. This waxing and waning course continued over 10 more months before the creamy deposits and subretinal fluid were noted to increase in size and distribution, resulting in a mild decrease in the patient’s BCVA to 20/30.

FIGURE 3A.

Color fundus photograph of the right eye of patient D, a 48-year-old woman, 2 months after presenting with a long history of fluctuating visual loss in the right eye associated with remitting and relapsing creamy choroidal infiltrates. Retinal pigment epithelium pigmentation is seen in the areas of older, regressed lesions.

FIGURE 3B.

Color fundus photograph of the right eye of patient D, a 48-year-old woman, 2 months after presenting with a long history of fluctuating visual loss in the right eye associated with remitting and relapsing creamy choroidal infiltrates. Creamy subretinal deposits inferonasal to the optic nerve head.

Because of the possibility of intraocular lymphoma, a diagnostic vitrectomy was performed, but analysis of the vitreal biopsy and washings (cytology and flow cytometry) was inconclusive. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and abdominal imaging were also negative.

A choroidal biopsy was therefore performed soon after and revealed low-grade B-cell lymphoma (Figure 4). Further treatment consisted of focal external beam radiotherapy targeted to the right eye and optic nerve (30 Gy in 15 fractions), resulting in complete regression of the choroidal lesions, leaving residual chorioretinal atrophy (Figure 5). Thus far, the patient has remained asymptomatic with no other systemic involvement and a final BCVA of 20/100 in the right eye.

FIGURE 4.

Histologic section of chorioretinal biopsy of patient D, a 48-year-old woman who presented with fluctuating visual loss in the right eye associated with remitting and relapsing creamy choroidal infiltrates. Biopsy revealed a diffuse infiltrate of mature lymphocytes throughout the choroid. Immunophenotyping was consistent with MALT-type lymphoma (hematoxylineosin, original magnification ×20)

FIGURE 5.

Healed chorioretinal biopsy site inferonasal to the optic nerve in patient D, a 48-year-old woman who presented with fluctuating visual loss in the right eye associated with remitting and relapsing creamy choroidal infiltrates due to a low-grade B-cell lymphoma. Further treatment consisted of external beam radiotherapy, resulting in marked regression of these subretinal infiltrates, leaving chorioretinal scars.

DISCUSSION

Before the advent of modern techniques for endoresection,7,8 diagnostic techniques for inflammatory diseases predominantly affecting areas of the posterior segment at or near the posterior pole were largely limited to analysis of intraocular fluids, such as aqueous and vitreous, and a tissue diagnosis was possible only in more anterior lesions with a transscleral biopsy.5,9,10 With endoresection, retinal and choroidal biopsies have now been used at an increasing frequency to provide a more definitive histologic diagnosis for atypical posterior segment diseases, particularly for atypical presentations of posterior uveitis.

Several case studies and a few case series have highlighted the usefulness of histologic diagnosis in such presentations, with the final diagnoses ranging from malignant B-cell lymphoma to infectious diseases such as cytomegalovirus retinitis, acute retinal necrosis, and toxoplasmosis.4–6,11,12 In all of these cases, a definitive or working diagnosis was achieved after the biopsy with successful further treatment. Postoperative complications have largely been limited to cataract,5,6 although secondary proliferative vitreoretinopathy and traction retinal detachment have also been described in patients who already had a retinal detachment from their disease prior to surgery.6,11

Although the advent of PCR and improved culture techniques have increased the yield in the diagnosis of many different diseases, such as toxoplasmosis and viral retinitis, from the analysis of intraocular fluids alone,13–18 our experience has shown that there is still a place for choroidal or retinal biopsies, as in five of the eight cases, diagnostic vitrectomy proved to be conclusive. The indications for biopsy should therefore include (1) progressive, sight-threatening choroidal/retinal lesions unresponsive to therapy based on clinical findings, (2) suspicion of malignancy, (3) sight-threatening involvement of the second eye despite treatment, and (4) negative vitreous analysis after diagnostic vitrectomy in the setting of any of the above.

Overall, in seven of the eight cases, the biopsy either provided a diagnosis or excluded infective or malignant diagnoses that enabled the successful tailoring of therapy. In five of these cases, malignant B-cell lymphoma was diagnosed, prompting a change of treatment from local or oral corticosteroid to either systemic chemotherapy or intravitreal methotrexate, with good response. In two cases (patients B and C), infective and malignant possibilities were excluded on the basis of histology and negative viral PCR and microbial and fungal cultures.

However, we have also shown that this technique is not infallible. In one case, despite an adequate biopsy in an area considered to be the active inflammatory edge of retinitis, the diagnosis was not successfully made until enucleation of the affected, nonseeing eye. The biopsy specimen was evaluated by two experienced eye pathologists with the specific diagnosis of lymphoma in mind. Despite immunophenotyping and gene rearrangement studies, a diagnosis of lymphoma could not be made on the basis of the biopsy results. In this case (patient E), the biopsy was misleading, such that a definitive diagnosis was made and appropriate therapy instituted only after enucleation when the fellow eye became involved. This is in contrast to other series4–6 reporting that a definitive diagnosis was not always obtained from the biopsy, but that other possibilities, such as malignancy and infection, could be excluded, resulting in appropriate therapy.

The possibility of toxoplasmosis was not considered likely in any of the cases on the basis of the patients’ clinical presentations. As a result, neither PCR to detect Toxoplasma nor Witmer coefficient testing was performed on any of the biopsy samples. Although identification of the Toxoplasma parasite on microscopy of retinal biopsy samples has been reported, the sensitivity of this method is far lower than other techniques, such as PCR.12 Therefore, it is possible, but unlikely, that the diagnosis of toxoplasmosis could have been missed with the approach used in the processing of our biopsies in the one case (patient B) without a definitive diagnosis.

Risks of endoresection include cataract, retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, choroidal hemorrhage, and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Although no postoperative complications were observed in any of our cases, the numbers in our case series are insufficient to conclude that this procedure has no morbidity.

Several investigators have recommended obtaining a retinal biopsy (via either a transscleral or an internal approach) in cases where malignancy or infection is being considered, largely because of the markedly different treatment that these conditions require in comparison to autoimmune uveitis.5,6 Chan and colleagues4 further suggested that a retinal biopsy be considered when the presenting condition was predominantly within the choroid and retina, with very little anterior chamber or vitreal inflammation. With the results from our series using an internal approach, we concur with these recommendations. However, it is important to realize that in cases where no definitive diagnosis is established and the disease process fails to respond to treatment based on the initial biopsy, or the vision in the other eye also becomes threatened, then a repeated biopsy, or enucleation (if the eye has no visual potential), is recommended.

On this note, retinal and choroidal biopsies are therefore best classified as being conclusive or inconclusive, rather than “positive” or “negative.” A conclusive biopsy is therefore one in which a definitive diagnosis can be made, and an inconclusive biopsy is where only nonspecific findings are observed, such as chronic inflammation with a polyclonal immunophenotype, or fibrosis.

In summary, we have found that retinal and choroidal biopsies can be extremely useful in the diagnosis and further management of atypical, aggressive presentations of uveitis. In this small series, we found the procedure to have a low risk of complications. Retinal and choroidal biopsies could be considered as a valid investigation earlier in the management of such cases, in which an early diagnosis may preserve visual function in the affected or contralateral eye. However, when biopsy results are inconclusive, an additional biopsy or enucleation should be considered if the disease process progresses or behaves atypically with treatment based on the initial biopsy findings.

Footnotes

Supported by unrestricted funds from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc, New York, New York, and the Stan and Madelle Rosenfeld Family Trust, Portland Oregon. Dr Rosenbaum is a Senior Scholar supported by Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ormerod LD, Puklin JE. AIDS-associated intraocular lymphoma causing primary retinal vasculitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 1997;5:271–278. doi: 10.3109/09273949709085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai LJ, Chen SN, Kuo YH, et al. Presumed choroidal atypical tuberculosis superinfected with cytomegalovirus retinitis in an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patient: a case report. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2002;46:463–468. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(02)00500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittra RA, Pulido JS, Hanson GA, et al. Primary ocular Epstein-Barr virus-associated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a patient with AIDS: a clinicopathologic report. Retina. 1999;19:45–50. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan CC, Palestine AG, Davis JL, et al. Role of chorioretinal biopsy in inflammatory eye disease. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1281–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston RL, Tufail A, Lightman S, et al. Retinal and choroidal biopsies are helpful in unclear uveitis of suspected infectious or malignant origin. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2002.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutzen AR, Ortega-Larrocea G, Dugel PU, et al. Clinicopathologic study of retinal and choroidal biopsies in intraocular inflammation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119:597–611. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peyman GA, Juarez CP, Raichand M. Full-thickness eye-wall biopsy: long-term results in 9 patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 1981;65:723–726. doi: 10.1136/bjo.65.10.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peyman GA, Raichand M, Schulman J. Diagnosis and therapeutic surgery of the uvea—Part I: Surgical technique. Ophthalmic Surg. 1986;17:822–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin DF, Chan CC, de Smet MD, et al. The role of chorioretinal biopsy in the management of posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:705–714. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunduz K, Shields JA, Shields CL, et al. Transscleral choroidal biopsy in the diagnosis of choroidal lymphoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;43:551–555. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman WR, Wiley CA, Gross JG, et al. Endoretinal biopsy in immunosuppressed and healthy patients with retinitis. Indications, utility, and techniques. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1559–1565. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moshfeghi DM, Dodds EM, Couto CA, et al. Diagnostic approaches to severe, atypical toxoplasmosis mimicking acute retinal necrosis. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:716–725. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bou G, Figueroa MS, Marti-Belda P, et al. Value of PCR for detection of Toxoplasma gondii in aqueous humor and blood samples from immunocompetent patients with ocular toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3465–3468. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3465-3468.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Figueroa MS, Bou G, Marti-Belda P, et al. Diagnostic value of polymerase chain reaction in blood and aqueous humor in immunocompetent patients with ocular toxoplasmosis. Retina. 2000;20:614–619. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Short GA, Margolis TP, Kuppermann BD, et al. A polymerase chain reaction–based assay for diagnosing varicella-zoster virus retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham ET, Jr, Short GA, Irvine AR, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome–associated herpes simplex virus retinitis. Clinical description and use of a polymerase chain reaction–based assay as a diagnostic tool. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:834–840. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140048006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knox CM, Chandler D, Short GA, et al. Polymerase chain reaction–based assays of vitreous samples for the diagnosis of viral retinitis. Use in diagnostic dilemmas. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)71127-2. discussion 44–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox GM, Crouse CA, Chuang EL, et al. Detection of herpesvirus DNA in vitreous and aqueous specimens by the polymerase chain reaction. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:266–271. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080020112054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]