Abstract

Purpose

To determine the utility (quality-of-life weight) associated with adult strabismus.

Methods

Time tradeoff utility values were measured in physician-conducted interviews with 140 adult patients with strabismus in a private practice setting. Patients also completed a questionnaire containing six items that rated the following aspects of disability: specific health problems, problems with tasks of daily living, problems with social interaction, self-image problems, concerns about the future, and job-related problems. Patients were characterized as presurgical or nonsurgical, and their diplopia and asthenopia were rated by the physician on a four-level scale.

Results

About 60% of all patients indicated willingness to trade part of their life expectancy in return for being rid of strabismus and its associated effects. The median utility was 0.93 (interquartile range, 0.83 to 1.0). A significantly smaller proportion (44%) of the nonsurgical patients (N = 41) appeared willing to trade time compared with surgical patients (68%; P = .009). Median utility in the presurgical patients was 0.90. Strong relationships were found between utility and the level of diplopia (P < .0001), and between utility and the level of asthenopia (P < .0001). Utility was correlated with all six disability ratings (all P ≤ .00062).

Conclusion

A majority of the patients interviewed would trade a portion of their life expectancy in return for being rid of strabismus and its associated effects. These results were validated by significant associations with diplopia, asthenopia, and disability.

INTRODUCTION

Strabismus in adults has recently become an increasing focus of attention. Although the management of adult strabismus has traditionally been regarded as difficult, good clinical and functional outcomes have been reported.1–9 A recent report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology10 concluded that surgical treatment of strabismus in adults is generally safe and effective. Also, several reports have shown that strabismus in adults is associated not only with functional deficits but also with psychosocial problems.9,11–15 These results suggest that the health value inherent in the treatment of strabismus in adults may be determined by a complex equation weighing cost not only with functional benefits but also with a variety of subjective, psychosocial improvements.

In modern health care, such patient-centered outcomes are increasingly recognized as important measures in decision making and policymaking. Cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analyses often include the effects of health management on the patients’ quality of life. Although it is widely appreciated that quality of life is a multidimensional trait, it is desirable for the purpose of cost-effectiveness analysis to capture quality of life in a single number: the “quality-of-life weight” or “utility,” defined on a continuous scale from 0 (corresponding to death) to 1 (corresponding to perfect health). In cost-utility analyses, the outcomes of interventions are thus evaluated by offsetting the cost with the utility gained. More specifically, the utility values associated with relevant health states are multiplied by the length of time that the patient spends in each health state to arrive at quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). The QALY has become the common currency for a wide variety of health outcomes and, by virtue of the numeric scale, can be used to compare outcomes not only within but also across diseases.16 Although such comparisons are not without problems,16,17 the use of utilities has become an accepted means of expressing quality of life for the purpose of different types of value analyses. In the field of ophthalmology, utilities have been measured for health states associated with a variety of conditions18–22 and have been used successfully for cost-utility analyses.23–27 Cost-utility analyses form the basis of value-based medicine, which takes evidence-based medicine to the next level by incorporating cost and effectiveness measures (including utility) into its analyses. For a snapshot overview of published cost-utility analyses in ophthalmology, see a recent extensive literature review by Brown and colleagues.28

In this study, we used a time tradeoff method 29 to assess the quality-of-life weight (utility) in adult patients with strabismus and validated the results by comparing utility values with both patient-perceived disability ratings and clinical ratings of diplopia and asthenopia.

METHODS

Consecutive adult patients with strabismus who visited our private practice setting were invited to participate. Participants were categorized as presurgical if they were scheduled (or planned to be scheduled) to undergo strabismus surgery; as postsurgical if they had recently undergone strabismus surgery; or as nonsurgical otherwise. For the analyses presented here, the results from postsurgical patients were excluded. The data in this study were obtained from 140 patients, mean age (± SD) 48 ± 17 years (range, 18 to 85 years), of whom 99 were presurgical and 41 were nonsurgical. (Five additional patients agreed to participate but declined to answer the time tradeoff question or were not able to produce a meaningful answer.)

Of the 140 patients, 69 had long-standing or recurring strabismus stemming from childhood, whereas 71 patients had strabismus that was acquired after childhood. (For the purposes of this study, childhood ends when vision is assumed to have reached maturity: around age 9 years.30) Participants were further characterized by ratings (performed by the treating physician, G.R.B. or D.R.S.) of their level of diplopia and asthenopia, each on a four-point Likert scale. Patients signed a written informed consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Participating patients were interviewed by the physician following a scripted protocol, asking the patient to estimate his or her own life expectancy (number of life years remaining). If no useful estimate was obtained, the patient’s life expectancy was estimated using gender-specific life tables31 instead. The patient was then asked if he or she would be willing to trade in a portion of the estimated life expectancy (off the end of his or her life) in return for being rid of strabismus and all its associated effects, and if so, how many years he or she would be willing to trade under those hypothetical conditions (the time tradeoff question). Time tradeoff utility was calculated according to the following:

Note that this equation yields the value 1 if the number of years traded is zero: the patient is not willing to trade any portion of the life expectancy and presumably values his or her current quality of life equal to that of perfect health. The utility decreases with increasing number of years traded, eventually approaching zero if the patient should indicate willingness to trade all of his or her life expectancy.

Participating patients also completed a six-item written questionnaire (see Appendix)32 in which they were asked to rate the severity of problems associated with their strabismus in the following aspects: specific health problems, problems with tasks of daily living, problems with social interaction, concern or doubts about the future, self-image problems, and job-related problems. All severity ratings were performed on a Likert scale from 1 (corresponding to no problems) to 10 (severe problems). In addition, gender, race, and the presence of comorbidities (defined as “other health problems that influence [the patient’s] quality of life”) were collected.

All data analyses were performed in STATISTICA (Statsoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma) using nonparametric statistics because of the nonnormal distribution of the utility values and the discrete nature of the rating scales for disability, diplopia, and asthenopia.

RESULTS

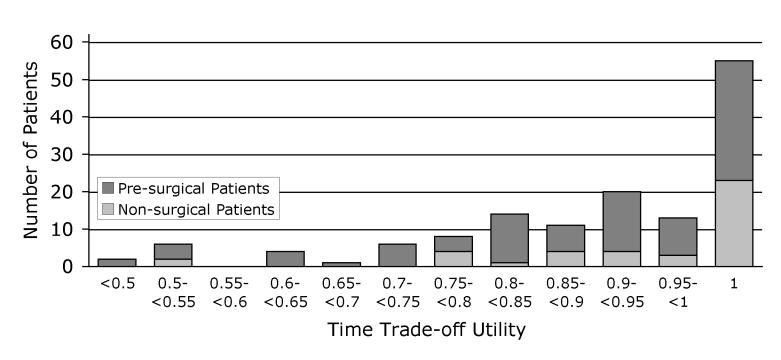

Overall, under the hypothesized condition outlined in the time tradeoff question, 85 patients (61%) indicated to be willing to trade in part of their life expectancy in return for being rid of strabismus and its associated effects. The distribution of time tradeoff utility values (Figure 1) had a median value of 0.93 (interquartile range, 0.83 to 1.0).

FIGURE 1.

Histogram showing the overall distribution of time tradeoff utility values in 140 consecutive adults with strabismus. The median of this distribution equals 0.93 (interquartile range, 0.83 to 1.0). A total of 85 patients (61%) indicated that they would be willing to trade part of their life expectancy in return for being rid of strabismus and all its associated effects. The remaining 55 patients returned a time tradeoff utility of 1 (ie, not willing to trade part of their life expectancy). Dark and light portions of each bar indicate the proportion of presurgical and nonsurgical patients, respectively

When analyzed separately by subgroups of patients, a larger proportion of the surgical patients than of the nonsurgical patients appeared willing to trade in part of their life expectancy (67 patients [68%] versus 18 patients [44%], respectively; P = .0009, z test for proportions). Also, the utility values returned by the surgical patients were lower than those returned by the nonsurgical patients (median, 0.90 versus 1.0, respectively; P = .013, Mann-Whitney U test). Between subgroups of patients with long-standing or acquired strabismus, no significant differences were found in the proportions of patients willing to trade time (41 patients [58%] versus 44 patients [64%]; P = .47, z test) or in the utility values (0.95 versus 0.92; P = .73, Mann-Whitney U test). These comparisons are summarized in Table 1, which also shows that no differences were found in time tradeoff utility between patients with and without comorbidities or between male and female patients.

TABLE 1.

OVERVIEW OF TIME TRADEOFF UTILITY RESULTS IN CONSECUTIVE ADULT PATIENTS WITH STRABISMUS

| GROUP | N | PATIENTS (%) INDICATING WILLINGNESS TO TRADE TIME* | PVALUE† | MEDIAN UTILITY (INTERQUARTILE RANGE) | PVALUE‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 140 | 85 (61%) | 0.93 (0.83–1.0) | ||

| Surgical | 99 | 67 (68%) | .009 | 0.90 (0.82–1.0) | .013 |

| Nonsurgical | 41 | 18 (44%) | 1.0 (0.88–1.0) | ||

| Long-standing | 69 | 44 (64%) | .47 | 0.92 (0.83–1.0) | .73 |

| Acquired | 71 | 41 (58%) | 0.95 (0.82–1.0) | ||

| Comorbidities | 58 | 36 (62%) | .78 | 0.90 (0.75–1.0) | .17 |

| No comorbidities | 82 | 49 (60%) | 0.95 (0.87–1.0) | ||

| Male | 67 | 38 (57%) | .35 | 0.96 (0.88–1.0) | .08 |

| Female | 73 | 47 (64%) | 0.90 (0.80–1.0) |

Number of patients willing to trade part of their life expectancy in return for being rid of strabismus and its associated effects, under the hypothesized conditions outlined in the time tradeoff method.

Differences between proportions were evaluated using the z test.

Group differences were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test

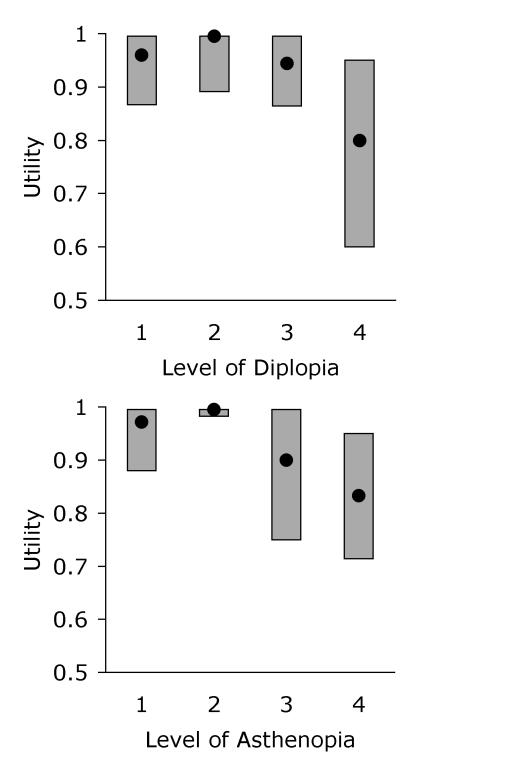

Figure 2 shows the relationship between utility values and the clinical ratings of the levels of diplopia and asthenopia. Significant effects of the level of diplopia (P = .048) and especially of the level of asthenopia (P < .0001) on utility were found (Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance). Linear trend analysis confirmed that higher (worse) levels of diplopia and asthenopia were associated with lower (worse) utility values (both P values < .0001).

FIGURE 2.

Box plots showing the relationship between time tradeoff utility in adults with strabismus and the physician ratings of each patient’s level of diplopia (top: 1 = None, 2 = In side gaze and/or upgaze only, 3 = In primary gaze and/or downgaze, 4 = Constant) and asthenopia (bottom: 1 = None, 2 = With prolonged effort, 3 = With minimal effort, 4 = Constant). In each box plot, the filled circle corresponds to the median utility, and the box spans the interquartile range (25th percentile to 75th percentile).

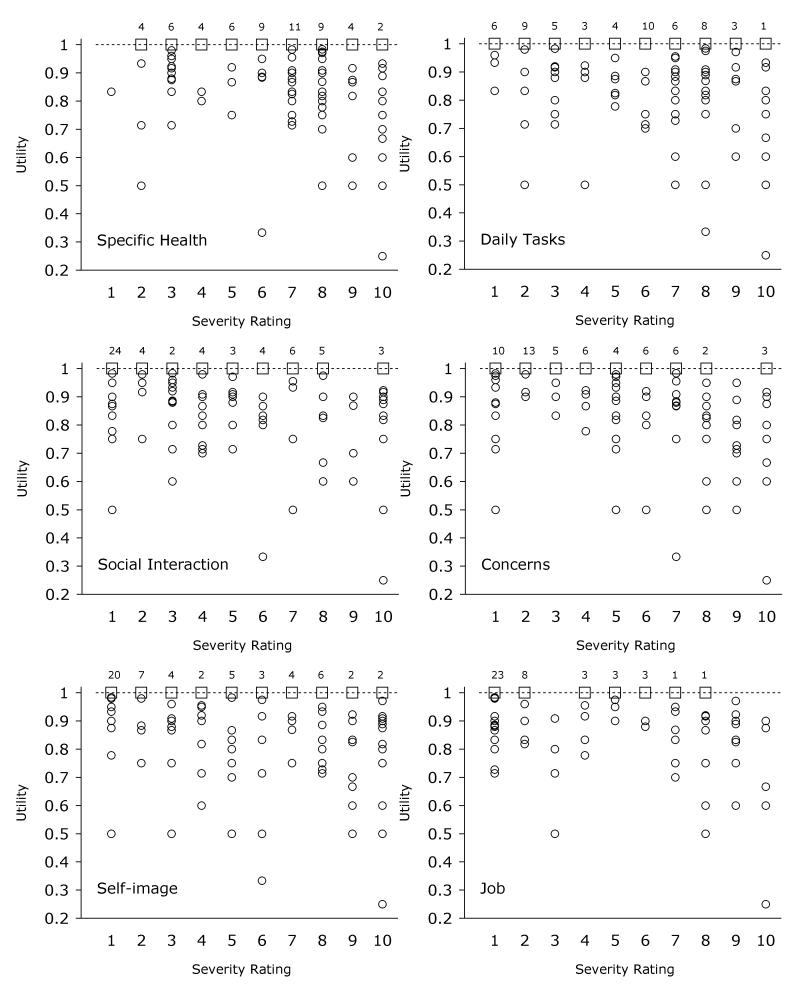

An overview of the severity ratings from the disability questionnaire is presented in Table 2, with specific health problems rated highest (median, 7 on the 10-point scale) and job-related problems lowest (median, 3 on the 10-point scale). The relationships between utility values and the patient-perceived disability ratings are also given in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 3. Strong correlations were found between utility and each of the six severity ratings (rs ranging from –0.29 to –0.42, all P values ≤. 00062; Spearman rank correlation).

TABLE 2.

MEDIAN DISABILITY RATINGS FOR SIX ASPECTS OF DISABILITY AND THE ASSOCIATIONS WITH TIME TRADEOFF UTILITY IN ADULTS WITH STRABISMUS

| DISABILITY (QUESTIONNAIRE ITEM) | MEDIAN SEVERITY (INTERQUARTILE RANGE) | ASSOCIATION WITH UTILITY (SPEARMAN RANK CORRELATION, RS) |

|---|---|---|

| Specific health | 7 (5–8) | −0.32 (P = .00013) |

| Daily tasks | 6 (3–8) | −0.29 (P = .00062) |

| Social interaction | 4 (1.75–7) | −0.31 (P = .00021) |

| Concerns | 5 (2–8) | −0.42 (P < .0001) |

| Self-image | 5 (2–8) | −0.37 (P < .0001) |

| Job | 3 (1–7) | −0.31 (P = .00017) |

FIGURE 3.

Scatter plots showing the relationships between time tradeoff utility values and each of the six severity ratings of patient-perceived disability in adults with strabismus. For clarity, multiple overlapping data points at 1.0 utility were replaced by single open squares with labels indicating the number of overlapping points in the original database. For utility values less than 1.0, open circles represent individual patients.

DISCUSSION

The utility associated with strabismus was measured in a large group of adult patients, and the results correlated strongly with both patient-perceived and clinical measures of disability. These data confirm the substantial decrement in quality of life—in terms of both disability and utility—caused by the disease strabismus. It is unknown whether these data will translate effectively to strabismus in children. A reasonable presumption may be that the quality of life decrements imposed by strabismus in children are equal to or exceed those of adults.

Results from patients who are meant to undergo surgical treatment (median utility, 0.90) are comparable to those reported in the literature for other ophthalmic conditions: The mean utility associated with untreated unilateral amblyopia (visual acuity 20/80 in the amblyopic eye, 20/20 in the sound eye) was shown to be 0.83.26 Patients with diabetic retinopathy and visual acuity between 20/20 and 20/25 in the best-seeing eye reported utility of 0.86.22 The same study found that age-related macular degeneration with visual acuity between 20/20 and 20/25 in the best-seeing eye corresponded to a mean utility of 0.84.22 For a wider comparison, the compilation by Bell and coworkers16 includes the following patient-based utilities (obtained with time tradeoff or standard gamble methods, or both) for health states associated with nonophthalmic conditions: mild stroke, 0.85; post–myocardial infarction, 0.88; angina with no chest pain symptoms, 0.87; partially controlled seizures, 0.79 (patients taking lamotrigine and having two to nine seizures per month), or 0.91 (less than two seizures per month while taking lamotrigine). (This compilation of utility data,16 organized by categories of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9], and references to the original studies can be found at http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/cearegistry.)

Utility was higher among participants who were not planning to have strabismus surgery than in the presurgical patients. The fact that more than half of the nonsurgical patients indicated no willingness for trading part of their life expectancy caused the median utility in this group to equal 1.0. Nonetheless, a sizeable minority (44%) of the nonsurgical patients returned a utility less than 1 (see the light bars in the histogram of Figure 1.)

Crucial in any cost-utility analysis of a treatment strategy is the utility differential between treated and untreated health states, rather than the absolute values of the utilities associated with these health states. Therefore, in the case of adult strabismus, long-term postoperative data are necessary to evaluate the utility gain. This gain (expressed in QALYs), when offset against the cost of treatment, can then be compared with cost-effectiveness (cost-utility) analyses of other conditions and treatments. Value-based medicine may thus form the basis for calculating the economic consequences and contributions of medical interventions in the treatment of strabismus and may be compared to other medical conditions and interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Ann Stout, MD, Casey Eye Institute, Portland, Oregon, for devising and letting us use the rating scales for diplopia and asthenopia.

APPENDIX: WRITTEN DISABILITY QUESTIONNAIRE (6 ITEMS) ADMINISTERED TO CONSECUTIVE STRABISMUS PATIENTS OLDER THAN 18 YEARS OF AGE

| Item | Wording | Rating | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instructions | Please indicate on a scale from 1 to 10 the degree to which your strabismus (eye misalignment) affects your life in the ways described. Foreachof the questions, answer '1' means 'no effect,' while '10' means 'severe effect.' | ||||||||||

| Rating scale |

1 (None) |

2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

10 (Severe) |

|

| Specific Health | Specific health problems—including poor vision, double vision, headaches/eyestrain, decreased field of vision, decreased depth perception, etc | ||||||||||

| Daily Tasks | Difficulty with non-work-related tasks of daily living—including walking, driving, reading, sports, etc | ||||||||||

| Social Interaction | Social interaction problems—including inability to maintain eye contact, decreased ability to communicate, social confusion, difficulty establishing and/or sustaining relationships, etc | ||||||||||

| Concerns | Concerns/doubts about the future—including worry about possible blindness, inability to work, read, etc | ||||||||||

| Self-image | Problems of self-image—including diminished self-confidence, self-esteem, and feelings of self-worth | ||||||||||

| Job | Job-related problems—including being hired, retained, and/or promoted | ||||||||||

REFERENCES

- 1.Wortham E, 5th, Greenwald MJ. Expanded binocular peripheral visual fields following surgery for esotropia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1989;26:109–112. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19890501-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kushner BJ, Morton GV. Post-operative binocularity in adults with long-standing strabismus. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:316–319. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball A, Drummond GT, Pearce WG. Unexpected stereoacuity following surgical correction of long-standing horizontal strabismus. Can J Ophthalmol. 1993;28:217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris RJ, Scott WE, Dickey CF. Fusion after surgical alignment of longstanding strabismus in adults. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31703-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kushner BJ. Binocular field expansion in adults after surgery for esotropia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:639–643. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090170083027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lal G, Holmes JM. Postoperative stereoacuity following realignment for chronic acquired strabismus in adults. J AAPOS. 2002;6:233–237. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2002.123399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beauchamp GR, Black BC, Coats DK, et al. The management of strabismus in adults—I. Clinical characteristics and treatment. J AAPOS. 2003;7:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(03)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mets MB, Beauchamp C, Haldi BA. Binocularity following surgical correction of strabismus in adults. J AAPOS. 2004;8:435–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fawcett SL, Felius J, Stager DR., Sr Predictive factors underlying the restoration of the macular binocular vision reflex in adults with acquired strabismus. J AAPOS. 2004;8:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mills MD, Coats DK, Donahue SP, et al. Strabismus surgery for adults. A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1255–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke JP, Leach CM, Davis H. Psychosocial implications of strabismus surgery in adults. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1997;34:159–164. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19970501-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satterfield D, Keltner JL, Morrison TL. Psychosocial aspects of strabismus study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1100–1105. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090080096024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menon V, Saha J, Tandon R, et al. Study of the psychosocial aspects of strabismus. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2002;39:203–208. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-20020701-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olitsky SE, Sudesh S, Graziano A, et al. The negative psychosocial impact of strabismus in adults. J AAPOS. 1999;3:209–211. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(99)70004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coats DK, Paysse EA, Towler AJ, et al. Impact of large angle horizontal strabismus on ability to obtain employment. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:402–405. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell CM, Chapman RH, Stone PW, et al. An off-the-shelf help list: a comprehensive catalog of preference scores from published cost-utility analyses. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:288–294. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnesen T, Trommald M. Are QALYs based on time trade-off comparable? A systematic review of TTO methodologies. Health Econ. 2005;14:39–53. doi: 10.1002/hec.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, et al. Utility values and diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:324–330. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown GC, Sharma S, Brown MM, et al. Utility values and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:47–51. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, et al. Quality of life associated with unilateral and bilateral good vision. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:643–647. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00635-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jampel HD, Schwartz A, Pollack I, et al. Glaucoma patients' assessment of their visual function and quality of life. J Glaucoma. 2002;11:154–163. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, et al. Quality of life with visual acuity loss from diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:481–484. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S, et al. Incremental cost effectiveness of laser photocoagulation for subfoveal choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1374–1380. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma S, Brown GC, Brown MM, et al. The cost-effectiveness of photodynamic therapy for fellow eyes with subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:2051–2059. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S, et al. Incremental cost-effectiveness of laser therapy for visual loss secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2002;9:1–10. doi: 10.1076/opep.9.1.1.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Membreno JH, Brown MM, Brown GC, et al. A cost-utility analysis of therapy for amblyopia. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:2265–2271. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.König HH, Barry JC. Cost effectiveness of treatment for amblyopia: an analysis based on a probabilistic Markov model. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:606–612. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.028712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown GC, Brown MM, Sharma S, et al. Value-based medicine and ophthalmology: an appraisal of cost-utility analyses. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2004;102:177–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torrance GW. Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal. J Health Econ. 1986;5:1–30. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(86)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott WE, Kutschke PJ, Lee WR. Adult strabismus. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1995;32:348–352. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19951101-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arias E. United States life tables, 2001. National vital statistics reports. Vol 52, No. 14. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. [PubMed]

- 32.Beauchamp GR, Black BC, Coats DK, et al. The management of strabismus in adults—III. The effects on disability. J AAPOS 2005. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]