Abstract

The efficacy of two different unconditioned stimuli (US) in producing conditioned taste aversion (CTA) was tested in rats after bilateral ibotenic acid (IBO) lesions of the gustatory nucleus of thalamus (TTAx) and the medial and lateral parabrachial nuclei (mPBNx, lPBNx). An initial study determined an equivalent dose for the two USs, LiCl and cyclophosphamide (CY), using non-lesioned rats. Subsequently, using a separate set of lesioned animals and their sham controls (SHAM), injections of CY were paired 3 times with one of two taste stimuli (CSs), 0.1 M NaCl for half the rats in each group, 0.2 M sucrose for the other half. After these conditioning trials, the CS was presented twice more without the US, first in a 1-bottle test, then in a 2-bottle choice with water. The acquisition and test trials had 2 intervening water-only days to assure complete rehydration. Two weeks later, the same rats were tested again for acquisition of a CTA using LiCl as the US and the opposite CS as that used during the CY trials. The SHAM and TTAx groups learned to avoid consuming the taste associated with either CY or LiCl treatment. The two PBNx groups failed to learn an aversion regardless of the US.

Keywords: Cyclophosphamide, Lithium chloride, Parabrachial nucleus, Thalamic taste area, Taste

1. Introduction

Lesions of the parabrachial nuclei (PBN) disrupt the acquisition of conditioned taste aversions (CTA) [1–5]. In contrast, lesions one synapse further on in the thalamic taste relay have little if any effect on the same task [6]. The generality of these effects has been tested with a variety of gustatory conditioned stimuli (CS) but with few unconditioned stimuli (US) other than lithium chloride (LiCl). The experiments summarized here compare the efficiency of the standard US, LiCl, with that of the cytotoxic agent cyclophosphamide (CY) in normal rats and rats with PBN and thalamic lesions.

Although it serves as an effective US in a CTA, cyclophosphamide is used primarily in studies of conditioned immune responses [CIR, 7]. The neural bases for CIR are less understood than for CTA, but evidence suggests that the two associative processes are partially separable [8]. This made cytotoxins interesting candidates for investigating the neural substrates for CTA USs because the same agent might require different neural substrates to support associative learning of different responses, i.e. behavior and the immune system. We chose CY because it was the most commonly used US in studies of CIR.

The regimen for CIR is essentially the same as that for CTA. Although the parameters can vary, the major difference is in the category of both the unconditioned (UR) and conditioned responses (CR). With CTA, the UR is licking the fluid CS, the UR is either less licking of the CS, refusal to lick at all, or rejection if the stimulus contact is forced. With CIR, the UR is the cell mediated and humoral immune responses to a standard dose of antigen, the CR is a depression of that response in the face of an identical challenge.

In the present case, we were interested in determining whether CY supported a CTAvia the same gustatory and visceral afferent pathways required when LiCl was the US. In most studies of CIR, the parameters differ from those of our standard CTA regimen. These differences made it necessary to conduct pilot studies using our standard paradigm to determine a CY dose that was roughly equivalent to that of our standard LiCl US.

After the dose determination, we used another set of animals to test whether the nature of the US had any effect on acquisition of a CTA in rats with ibotenic acid lesions in the PBN, the gustatory thalamus, or in sham controls. Ascending taste and vagal visceral afferent pathways are parallel, at least through the medulla and pons [9,10]. It is now clear that lesions of the PBN can block CTA in at least two ways. Medial or gustatory PBN damage prevents taste and visceral afferent associations [11,12]. Lateral or vagal PBN lesions appear to interfere with the visceral afferent activity produced by the LiCl US [3,4]. These differences prompted us to prepare separate groups of animals—one with PBN lesions centered medially, the other with lesions centered laterally. If LiCl and CY produced their effects via the same visceral afferent mechanisms, then we would predict that both the medial and the lateral PBN lesions would block acquisition of a CTA regardless of the US. If CY supported CTA via different mechanism, the medial PBN lesions might still block a learned aversion, but lateral damage probably would not.

All animals used in this study were treated in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the Penn State College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the experimental protocols.

2. Experiment 1: cyclophosphamide conditioned taste aversion and extinction

The rats in this pilot experiment had prior experience with sucrose in a CTA, so we substituted Polycose as the CS because they were naïve to this glucose polymer. Although normally highly preferred by rats, other experiments indicate that Polycose fails to generalize to sucrose [13–15].

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Animals

Twelve, adult male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) weighed between 400–600 g at the start of the experiment. They were individually housed in hanging, wire-mesh, stainless steel cages in a colony room with automatically controlled temperature (21 °C), humidity, ventilation, and light cycle (12:12-h light–dark, lights on at 0700 h). Behavioral testing was conducted in the home cage during the light phase. The rats had access to standard laboratory diet (Rodent Diet W 8604; Harlan Teklab, Madison, WI). Water was available ad libitum except as noted. Rats were assigned into 4 groups of three each by matching body weight (Groups A–D).

2.1.2. Chemicals and solutions

The CS was a 0.03 M glucose-polymer solution (Polycose®, Ross Products Division, Abbot Laboratories, Columbus, OH). Cyclophosphamide (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) dissolved in sterile water for injection at a concentration of 25 mg/ml [16] or 0.15 M LiCl served as the US. Distilled, deionized water (dH2O) or Polycose was available in a 100-ml inverted graduated cylinder with a silicone stopper and stainless steel spout mounted on the front of the cage.

2.1.3. Baseline training

The rats were adapted to a deprivation schedule in which they had access to dH2O for 15 min every morning (0900–0915 h) and for 1 h every afternoon (1400–1500 h). Food was available ad libitum except during the morning 15-min intake tests. When dH2O intake stabilized, after about 2 weeks, baseline intake was recorded for an additional 7 days. (See Table 1 for naming conventions, time lines, and procedures for each group). Fluid intakes were measured to the nearest 0.5 ml.

Table 1.

Experiment 1 – Groups, numbers of subjects, and timeline

| LiCl [0.15 M] | Cyclophosphamide [CY, 25 mg/ml]

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US: Injection(s) | 85 mg/kg | 5 mg/kg | 15 mg/kg | 45 mg/kg |

| Subjects/group | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| ||||

Fluids: conditioned stimulus (CS) 0.03 M Polycose (P) and deionized, distilled water (w). Arrows indicate intraperitoneal injection of unconditioned stimulus (US) 15 min after CS intake.

For statistical analysis, baseline AM water intake for each groups was calculated from the last 3 days (Pre-ACQ) before the first acquisition trial.

n-ACQ, nth acquisition trial; 1-B, one-bottle test; 2-B, two-bottle test.

2.1.4. CTA acquisition and test procedure

The details of CTA training have been described elsewhere [17]. Briefly, the rats were given three conditioning trials and two test trials as follows. On day 1 (AM) of the trial period, all rats received 15 min access to the CS, 0.03 M Polycose, instead of dH2O. Within 15–30 min of the CS removal, the rats were injected intraperitoneally (ip) with the standard US, 85 mg/kg (1.33 ml/100 g) of 0.15 M LiCl (Group A) or with 5, 15, or 45 mg/kg of CY (25 mg/ml; Groups B, C, and D, respectively). The same procedure was repeated twice more (Days 4 and 7). On the 2 mornings intervening between trials, all rats had 15 min access to dH2O. On the first test trial (Day 10), all rats were again given 15 min access to the CS solution but no injection followed. The second test (Day 13) consisted of a 15 min, 2-bottle choice between the CS and dH2O, again without any subsequent injections. As during training, throughout the trial period all rats had 1-h access to dH2O in the afternoon.

2.1.5. Extinction procedure

After the initial 2-bottle trial, another 3-day cycle was instituted for extinction. On Days 1 and 2, all rats had 15 min, morning access to the Polycose CS alone. On Day 3, the 2- bottle choice between the CS and dH2O was offered in the morning. As previously, all rats had dH2O in the afternoon. This morning cycle was repeated until intake of the CS and dH2O on the choice day was statistically equivalent. On the choice days, bottle positions were alternated.

2.1.6. Data analysis

All data are presented as mean±standard error (SEM) and were analyzed by standard analyses of variance (ANOVAs; Statistica ver. 6.0, StatSoft® Inc., Tulsa, OK). When appropriate, paired comparisons were performed using the post hoc Newman–Keuls procedure. The extinction test data required two-factor (Groups×Cycles) ANOVAs. Statistical rejection was set at p<0.05.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. CTA acquisition and testing

At the two higher doses (15 and 45 mg/kg), cyclophosphamide produced a CTA to Polycose in one trial that was equivalent to the LiCl-induced aversion (Fig. 1A, C, and D; [F (3,8)=16.99, p<0.001]). The lowest dose of CY (5 mg/kg) did not affect CS intake across trials (Fig. 1B). Post hoc assessment indicated that, with trial by trial comparisons, no significant differences existed between the LiCl, 15-mg/kg CY, and 45-mg/kg CY groups (all ps>0.05), but that these 3 groups differed from the 5-mg/kg group on trials 2–5 (all ps<0.01). During baseline (Fig. 1A–D, before Trial Day 1), morning dH2O intake was equivalent across all groups [F(3,8)=0.87, p>0.05] and remained so on the intervening 2-day dH2O trials between CS–US trials [F(3,8)=3.74, p>0.05]. Although intake of 0.03 M Polycose by the 5-mg/kg group (Fig. 1B) tended to increase across trials, this trend was not significant (all ps>0.05).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of a conditioned taste aversion (CTA) in rats induced by the unconditioned stimuli (US) cyclophosphamide (CY) and lithium chloride (LiCl). Morning 15-min fluid intakes (mean±SEM) for the last 3 days of water baseline (Pre-ACQ) and the 14-day experimental period (Days 1 to 14). The solutions were deionized, distilled water (dH2O) and 0.03 M Polycose, the conditioned stimulus (CS). Illness was induced by intraperitoneal (ip) injections of 0.15 M LiCl at the dose of 1.33 ml/100 g (85 mg/kg, Panel A), or 25-mg/ml CYat doses of 5, 15, and 45 mg/kg (Panels B, C, and D, respectively). The CS was followed by US injections on 3 acquisition trials (Days 1, 4, and 7). Day 10 was a one-bottle test (1-B) with the CS but no US; Day 13, a two-bottle test (2-B) with the CS, dH2O, and no US. In each panel, open squares (□) equal intake of 1-B dH2O during 15 min AM access; half-closed square (◨) equals intake of 2-B dH2O. Closed-triangles (▴) equal intake of 1-B CS Polycose trials and test; semi-closed triangle (◭) equals intake of the CS in a 2-B test. (***, p<0.001).

During the morning 15-min, 2-bottle intake test (CS vs. dH2O), none of the LiCl rats (Group A) drank detectable amounts of Polycose. The smallest quantity ingested by a 5-mg/kg CY rat (Group B) was 2.0 ml; the average was 10.67 ml. The 5-mg/kg CY group drank significantly more than the other 3 groups (all ps<0.05), which did not differ significantly from one another (ps<0.05). During the afternoon, water intake did vary. The 45-mg/kg CY group drank the most (11.9 ml) and the LiCl group, the least (5.6 ml).

2.2.2. Extinction

In the 2-bottle trials, the 5.0-mg/kg CY rats, which failed to exhibit a CTA, rapidly developed a preference for the Polycose CS compared with dH2O ([F(9,36)=4.01, p<0.01]; Fig. 2B). Post hoc assessment revealed that Polycose intake was significantly different from dH2O by the 3rd cycle, i.e. Day 9, of the extinction sequence (p<0.01). Their 2-bottle CS intake differed from the CS intake of the other 3 groups [F(3,8)= 19.96, p<0.001] and tracked their 1-bottle licking of Polycose throughout the 30 day period.

Fig. 2.

Three day extinction cycles of the conditioned taste aversions (CTA) induced by cyclophosphamide (CY) and lithium chloride (LiCl). Morning 15-min fluid intake (mean±SEM) of the 0.03 M Polycose conditioned stimulus (CS), and deionized, distilled water (dH2O). These 3-day cycles consisted of 2 days exposure to the CS alone (1-B), then a one-day 2-bottle (2-B) choice between dH2O and the CS. Cycles began the day after the first 2-B preference test. Closed (▲) and half-closed (◭) triangles represent the CS intake in 1-B and 2-B tests, respectively; semi-closed squares (◨) denote the intake of dH2O in the 2-B tests (**, first significant difference in 2-B tests, p<0.01; ns, first no significant difference in 2-B tests).

The LiCl rats extinguished their aversion to Polycose by the 5th cycle, i.e. Day 15: the first day on which their intake of the CS and dH2O was statistically equivalent ([F(9,36)=24.53, p<0.001], post hoc p=0.43; Fig. 2A). The Polycose CTAs resulting from the two higher doses of CY, however, required 10 cycles (30 days) to reach the same criterion (15 mg: [F(9,36)= 4.00, p<0.01], post hoc p=0.19 and 45 mg: [F(9,36)=4.76, p<0.001], post hoc p=0.91; Fig. 2C and D, respectively).

2.3. Discussion

As expected, an injection of LiCl shortly after sampling a distinctive taste, 0.03 M Polycose, produced a dramatic reduction in intake of this fluid on subsequent exposure. The 15-mg and 45-mg doses of cyclophosphamide had similar effects, but a 5-mg dose did not alter intake even after 3 pairings with the CS. In the next set of experiments, we chose the 15-mg/kg dose for the following reasons. This dose approximated the acquisition curve produced with our standard dose of LiCl. The higher dose of CY produced a transient rash beginning the day after the second injection. It disappeared a few days after the last injection. Finally, although difficult to confirm statistically due to the small groups (n=3 in each), the higher dose appeared to induce a more extreme aversion to the CS.

The extinction data demonstrated clearly that using just the acquisition rate of a CTA is not adequate for comparing the efficacy of different USs, presumably due to a floor effect. Although the acquisition curves are virtually identical, a CTA produced with the 15-mg dose of CY required twice as long to extinguish as one elicited by LiCl. This also was true of the 45-mg dose of CY but, in extinction, it delayed the initial sampling of the CS by a week compared with the 15-mg dose (CS-only days in Fig. 2C and D).

3. Experiment 2: central gustatory lesions and conditioned taste aversions

Once an appropriate dose of CY was established, we tested whether lesions of brainstem and thalamic relays would affect the efficacy of this US in the same manner as LiCl. In separate groups of animals, bilateral, electrophysiologically guided, ibotenic acid (IBO) lesions were aimed at the parvicellular tip of the ventroposteromedial nucleus of the thalamus (thalamic taste area; TTAx), the pontine medial parabrachial region (mPBNx), and the lateral PBN (lPBNx).

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Animals

Twenty-four, experimentally naïve, male SD rats, weighing 400–500 g and approximately 120 days old at the beginning of the CTA experiment, were obtained from the same source and housed under the same conditions as in the Experiment 1.

3.1.2. Surgery

The rats were assigned to one of four groups (n=6) defined by the location of their lesions (TTAx, mPBNx, lPBNx, and SHAM). The SHAM was a control group identical to those with lesions except that instead of 150-nl infusions of IBO, they received an equal volume of phosphate buffer saline (PBS), the IBO vehicle. The surgical procedures closely follow those used elsewhere [12,17]. Briefly, the rats were food deprived overnight. Approximately 15 min prior to surgery, each rat was weighed and injected with atropine (0.1 mg, ip) and Gentamicin (4.0 mg, ip). The rat was then anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg, ip) and mounted in a stereotaxic apparatus equipped with blunt ear bars (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Supplemental doses of barbiturate (5.0 mg, as needed) maintained the surgical level of anesthesia throughout the procedure.

With the skull exposed and leveled, ~2.0 mm diameter holes were trephined over the intended injections sites. For the medial and lateral PBN, these holes were centered 1.8 mm lateral to the midline and 11.5 mm posterior to bregma (β). Both the recording electrode and the IBO pipette were angled 20° rostral-caudally with the tip rostral. For the thalamus, the corresponding coordinates were 1.2 mm lateral and 3.5 mm posterior with the probes vertical. Gustatory responses were identified in either the pons or the thalamus by advancing a glass insulated tungsten microelectrode in 100–200 μm steps and stimulating the anterior tongue with 0.3 M NaCl and dH2O. When the sapid NaCl produced an unequivocal neural response, the coordinates were noted and the process repeated on the contralateral side. Subsequently, the recording electrode was replaced with an injection pipette that was glued onto the tip of a Hamilton 1.0-μl syringe and filled with ibotenic acid (20 μg/μl in PBS; Research Biochemicals International, Natick, MA). For the mPBN and the TTA, the pipette was positioned using the coordinates established during recording. The position for the lPBN was 0.4 mm anterior and lateral to the recording coordinates lowered to the same depth. In most instances, it was possible to record via the pipette to confirm the presence of taste responses in the mPBN and TTA and their absence in the lPBN. Once in place, IBO (150 nl) was infused over 10 min. The pipette was removed 15 min after the end of the infusion.

3.1.3. Baseline training and CTA procedure

After 2 weeks for recovery, the rats were placed on the same water deprivation regimen used in Experiment 1, i.e. 15 min AM access and again for 1 h PM. Once intake was stable for 7 days, the rats had two rounds of CTA training, each following the protocol from Experiment 1, i.e. 3 CS–US pairings, one 1-bottle test, and one 2-bottle test with 2 AM water days between each trial. The first sequence used CY (15 mg/kg) as the US; the second, LiCl (85 mg/kg). The CSs were 0.2 M sucrose and 0.1 M NaCl. These were counterbalanced within groups and across the USs.

3.1.4. Histology

After completion of all behavioral experiments, the animals were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg ip), then perfused intracardially first with heparinized PBS (5 min), followed by 4% (w/v) buffered paraformaldehyde (25 min). The brains were removed and postfixed for 24–48 h in a solution of 30% (w/v) sucrose plus 4% paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, they were blocked, frozen, and sectioned coronally at 50 μm on a freezing microtome. Alternate series of sections were stained for the specific neuronal protein NeuN using standard immunohistochemical techniques [18,19]. Appropriate sections were digitized and the stored images further analyzed (Optimas®, Bioscan, Edmonds, WA). The adequacy of the lesions was judged by comparing the areas without neurons with similar sections from the control brains and descriptions in the literature [9,20].

3.1.5. Data analyses

The data were analyzed using analysis of variance (GLM procedure, Statistica 6.0, StatSoft®). When appropriate, post hoc assessments were conducted with the Newman–Keuls Test. The criterion for statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Anatomical

Histological analysis revealed that 5 TTAx, 5 mPBNx, and 6 lPBNx rats had bilateral lesions that included most or all of the target area (Fig. 3). The thalamic lesions were large but quite uniform with extensions that spread laterally along the dorsal edge of the medial lemniscus, medially to join across the midline, and dorsally up the pipette track just lateral to the habenula. In addition to destroying the thalamic gustatory relay, these lesions involved the central medial and parafascicular nuclei, and the mediodorsal complex. In 4 of the mPBNx rats, the lesions included all of the medial nucleus and most of the lateral subnuclei dorsal to the brachium conjunctivum (BC), but spared varying amounts of the lateral subnuclei that extend rostrolateral to the BC. In these rats, cell loss extended into the supratrigeminal area and the locus coeruleus. In the fifth mPBN rat, the damage was confined to the medial nucleus and the lateral nuclei above the ‘waist area’ of the BC. It was complete on the right but, on the left, some cell sparing occurred. This damage corresponded closely with the electrophysiologically identified gustatory area of the PBN [21].

Fig. 3.

Photomicrographs of bilateral coronal sections from the brains of rats stained for neurons with NeuN immunohistochemistry. Panels A and B show the bilateral electrophysiologically guided ibotenic acid (IBO) lesions made at the thalamic taste area (TTAx). Panels C and D, a similar level through the TTA in a sham control rat (SHAM). Panels E and F, IBO lesions aimed at the medial parabrachial nuclei (mPBNx). Panels G and H, IBO lesions aimed at the lateral parabrachial nuclei (lPBNx). Panels I and J, the PBN in a SHAM rat. Arrows point to the target area of the lesion, black dots outline the extent of complete neuronal degeneration. Scale bar=0.5 mm. (BC, brachium conjunctivum; CP, cerebral peduncle; fr, fasiculus retroflexus; LC, locus coeruleus; lPBN, lateral parabrachial nuclei; ml, medial lemniscus; MoV, Motor neuron of trigeminal nerve; mPBN, medial parabrachial nuclei; pf, parafascicular nucleus; STA, supratrigeminal area; VPM, ventroposteromedial thalamic nuclei; 3V, third ventricle).

All six of the lPBNx rats had bilateral damage to the anterior lateral nuclei and, with one exception, the lesions spared much or all of the medial, gustatory areas. In the exception, the entire PBN was destroyed on both sides. What sparing of the lateral nuclei that did occur was posterior and medial. In most instances, the damage extended into the reticular formation rostral to the trigeminal motor nucleus. In fewer cases, the principal and motor trigeminal nuclei were included, but never bilaterally. Thus, five TTAx, five mPBNx and six lPBNx rats, together with six SHAM-lesioned subjects, provided the behavioral data analyzed below.

3.2.2. CTA acquisition

The performance of the four groups of rats during the two conditioning rounds is summarized in Fig. 4. Baseline morning water intake was stable across groups and across both CTA sequences [F(18, 240) =0.81; p <0.69]. Separate ANOVAs indicated that the CS moiety failed to influence the CTA, so the data have been combined (main effect of CS [F(1,42)=0.10, p = 0.75]; USs × Trial (1–4) interaction, [F(3, 126) = 0.62, p<0.60]). The two CSs were counterbalanced between the two USs. The six SHAM rats learned to avoid the CS after one pairing with LiCl (Fig. 4A; [F(9,54)=5.30, p<0.001], post hoc p<0.001). The TTAx rats also learned the task, although they needed two trials to reach complete avoidance, (Fig. 4B, p<0.001). Neither the mPBNx nor the lPBNx groups learned an aversion to the CS (Fig. 4C and D; all ps>0.05).

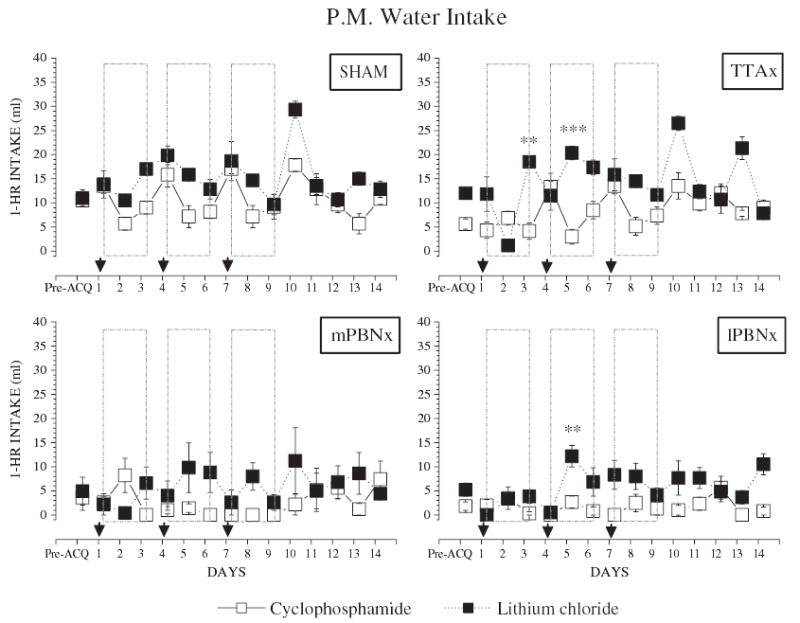

Fig. 4.

Comparison of conditioned taste aversion (CTA) induced by the unconditioned stimuli (US) cyclophosphamide (CY) and lithium chloride (LiCl) paired with conditioned stimuli (CSs) in rats with central gustatory lesions and their sham controls. Group means (±SEM) of 15-min AM fluid intake during the last 3 days of water baseline (Pre-ACQ) and the 14-day experimental period (Days 1 to 14). On the three acquisition trials (Days 1, 4, and 7), the CS was followed by an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of the US. Day 10 was a 1-bottle (1-B) test with the CS but no US. Day 13 was a two-bottle (2-B) test with the CS, dH2O, and no US. In the first round the US was 15-mg/kg CY (bottom panels); in the second, 85-mg/kg LiCl (top panels). The two CSs were 0.1 M NaCl and 0.2 M sucrose. They were counterbalanced across the groups and USs, but the results are collapsed here. Top panels (A–D); LiCl US. Bottom panels (E–H); cyclophosphamide US. Open squares (□) equal 1-B dH2O intake during the 15-min AM access periods. Closed triangles (▴) equal 1-B CS intake in 1-B tests. Half-closed squares (◨) equal dH2O intake in the 2-B test; semi-closed triangles (◭), equal CS intake in the 2-B test. (**, p<0.01; and ***, p<0.001).

When cyclophosphamide was the US, the results were essentially identical to those produced by LiCl; only subtle differences were evident (see Fig. 4E–H). Both the SHAM and TTAx animals learned the CTA, albeit more slowly than with the LiCl US, (see Fig. 4E and F vs. A and B; [F(9,54)=13.40, p<0.001]). Both PBNx groups again failed to learn an aversion (mPBNx, [F(3,9)=1.67, p =0.24]; lPBNx, [F(3,12)=0.45, p=0.72]). When the CY was effective, i.e. with the sham controls and TTAx rats, morning dH2O intake decreased the day after a trial, but rebounded on the 2nd intertrial day (see Fig. 5 for detailed comparison of the afternoon 1-hr dH2O intake). This pattern was not as evident when these rats received LiCl as the US and it was absent in all of the PBNx rats.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of afternoon water intake of rats with central gustatory lesions and their sham controls. Group means (±SEM) represent 1-h PM deionized, distilled water (dH2O) intake during the last 3 days of water baseline (Pre-ACQ) and the 14-day experimental period (Days 1 to 14). The three acquisition trials were performed in the morning on Days 1, 4, and 7 (arrows). Day 10 was a 1-bottle (1-B) test with the CS but no US. Day 13 was a two-bottle (2-B) test with the CS, dH2O, and no US. Closed squares (▪), LiCl; open squares (□), cyclophosphamide. (**, p<0.01; and ***, p<0.001).

4. Discussion

Bilateral lesions of the parabrachial nuclei prevent the acquisition of a conditioned taste aversion [22]. Data support two interpretations of this effect. Lesions of the medial (gustatory) PBN appear to disrupt the association of a taste CS with the malaise produced by the US, even though the animal can use both sensory events in other contexts, such as a conditioned flavor preference [11,12]. Lesions of the lateral PBN apparently block the visceral sensory activity that constitutes the malaise from reaching the forebrain [3,4]. The blockade produced by medial PBN lesions is broad but not complete. Taste and some olfactory stimuli fail to become aversive even after 3 pairings with LiCl. When a CS, such as capsaicin, is mediated by the trigeminal system, the same lesions do not interfere with learning an aversion [11]. The spectrum of US stimuli rendered ineffective by lateral PBN damage is less well studied. The standard is LiCl, but one study used scopolamine, ethanol, and intragastric hypertonic NaCl. In single trial tests, lateral PBN lesions blocked the effects of the first three USs, but not of intragastric saline [23].

We compared a cyclophosphamide US with LiCl across medial PBN, lateral PBN, and thalamic lesions because the cytotoxic agent is commonly used in studies of conditioned immune responses [16], and these lesions can have differential effects on CTAs. Using our standard paradigm, the nature of the US made little difference. With one exception, the medial and lateral PBN lesions prevented the acquisition of the CTA regardless of the CS or the US used. Rats with thalamic gustatory damage learned both CTAs essentially the same as did the controls. The exception was a mPBNx rat that had a relatively small lesion with some ipsilateral neural sparing within the gustatory area. This animal failed to learn a CTA to a sucrose CS when paired 3 times with CY, but subsequently reduced its intake of 0.1 M NaCl when that CS was paired with LiCl injections. Even this learning was relative because the initial intake of the NaCl CS was nearly double the baseline dH2O consumption, i.e. 31 vs. 17.5 ml. After 3 US–CS pairings, the rat was still drinking ~10 ml of NaCl.

Although CY appears to be processed similarly to LiCl in CTA, some differences do exist. In the pilot experiment, the 15-mg/kg dose of CY produced a one trial CTA equivalent to that with our standard dose of LiCl, but extinction of the former took twice as long as the latter. In the main experiment, however, the controls required up to three CY pairings to get CS intake to near zero, but LiCl only one. This difference resulted from a founder effect. In the first and second experiment, the first pairing of 15-mg/kg CY, decreased subsequent CS intake by 11.4 and 11.7 ml, respectively. The difference was in the initial CS intake, 14.0 ml in the first experiment, 19.5 in the second. Thus, in the Experiment 1, trial 2 CS intake was only 2.7 ml, but in Experiment 2, it was 5.1 ml higher, i.e. 7.8 ml. In any event, the difference is not critical because both CSs failed to support a CTA after PBN lesions even after 3 CS–US trials.

This difference in US efficacy was also reflected in another measure between the responses to CY and LiCl morning water intake on the days between pairings. The two water trials intervening between the CS–US pairing were designed to permit rehydration. In the control and TTAx groups, after pairings with LiCl, subsequent AM water intake was similar to pre-pairing baseline (Fig. 4A and B; [F(9,36)=1.76, p=0.11] and [F(9,27)=2.07, p=0.07], respectively). After pairings with CY, the same rats depressed their AM water intake on the first day [F(9,36)=11.37, p<0.001], then tended to recover on the second [F(9,36)=2.13, p=0.052]. These data prompted two hypotheses. First, the CY induced a particularly long lasting malaise that depressed water intake the next morning. Second, the nature of the CY malaise was such that it produced a short-lived generalization to the morning test circumstances and this depressed water intake. Both hypotheses imply that CY is more effective on some dimension than LiCl. This possibility is supported by the CY extinction data from Experiment 1, but not by the slower rate of aversion learning produced by the cytotoxin in Experiment 2.

A third possible reason for the depression of morning water intake the day after a CY injection arises from the potent antidiuresis activity of this compound that is not shared by LiCl. This results in dilutional hyponatremia, i.e. increased water reabsorption [24]. The effect is mediated by direct action of CY or its metabolites on the renal tubule, begins 4 to 12 h after injection, and lasts as long as 12 h [24–26]. This suggests that the next morning the CY-treated rats were relatively less dehydrated and, consequently, drank less during their 15 min access than the LiCl-treated group (Fig. 4A, B, E and F). This difference cannot be explained by increased PM water intake the preceding day, because the controls and TTAx rats actually drank less afternoon water during CY trials than after LiCl injections (6.66±1.80 vs. 12.07±3.64 ml; [F(1,36)=35.20, p<0.001]).

Although TTAx rats displayed CY-induced depression of morning water intake, medial and lateral PBNx rats did not (Fig. 4F, G and H). This is consistent with the role of the PBN, but not the TTA, in the regulation of fluid intake in response to physiological challenges [6,27,28]. For instance, subcutaneous injection of angiotensin II or isoproterenol stimulates water drinking. This effect is greatly augmented following lesions of the PBN [27]. Moreover, injections of a serotonergic antagonist into the PBN augments water intake under conditions of 24 h water deprivation or diuresis (i.e. furosemide induced urinary water and sodium loss; 27). One interpretation of the present data is that the PBN also plays a role in the regulation of water intake during conditions that involve expansion of the extracellular fluid space.

The differences in water intake reflect the fact that the two US chemicals have a number of effects that only partially overlap [29,30]. Most unconditioned stimuli in the CTA literature produce nausea and even vomiting in humans [31,32]. This is true of both LiCl and CY. Stimuli that evoke nausea typically activate vagal afferent fibers, the area postrema, or both. Both of these afferent systems have axons that relay in the PBN [10,33], so it is not surprising that lesions there block the ability of both compounds to support CTA learning. In order for this learning to occur, some relevant neural signals must reach the forebrain, because chronic decerebrate rats cannot acquire or retrieve a CTA [34].

Although LiCl and CY share the potential for inducing nausea, they do differ in other aspects. Perhaps their most prominent difference is the ability to suppress immune function—CY does, LiCl does not [7,16]. It is now well established that immune suppression also can be classically conditioned and this often is accomplished using a gustatory CS [35]. As a follow up to the current study, it would be interesting to determine if PBN damage would block the acquisition of both a CTA and a conditioned immune response as has been shown with lesions of the gustatory cortex [8].

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DC 00240 and DC 05435. We thank Dr. Han Li for assistance with the lesions, Kathy J. Matyas and Nellie Horvarth for assistance with histology. The authors also thank Anne E. Baldwin for comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Spector AC, Norgren R, Grill HJ. Parabrachial gustatory lesions impair taste aversion learning in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:147–61. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto T, Fujimoto Y, Shimura T, Sakai N. Conditioned taste aversion in rats with excitotoxic brain lesions. Neurosci Res. 1995;22:31–49. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00875-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reilly S, Trifunovic R. Lateral parabrachial nucleus lesions in the rat: long- and short-duration gustatory preference tests. Brain Res Bull. 2000;51:177–86. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reilly S, Trifunovic R. Lateral parabrachial nucleus lesions in the rat: aversive and appetitive gustatory conditioning. Brain Res Bull. 2000;52:269–78. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reilly S, Trifunovic R. Lateral parabrachial nucleus lesions in the rat: neophobia and conditioned taste aversion. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55:359–66. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00517-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scalera G, Grigson PS, Norgren R. Gustatory functions, sodium appetite, and conditioned taste aversion survive excitotoxic lesions of the thalamic taste area. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:633–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ader R, Cohen N. Behavioral conditioned immunosuppression. Psychosom Med. 1975;37:333–40. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197507000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacheco-Lopez G, Niemi M-B, Kuo W, Harting M, Fandrey J, Schedlowski M. Neural substrates for behaviorally conditioned immunosuppression in the rat. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2330–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4230-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundy Jr RF, Norgren R. Gustatory system. In: Paxinos G, Mai J, editors. The rat nervous system. 3rd ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2004. p. 891–921.

- 10.Saper CB. Central autonomic system. In: Paxinos G, editor. The rat nervous system. 3rd ed. New York: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. p. 761–96.

- 11.Grigson PS, Reilly S, Shimura T, Norgren R. Ibotenic acid lesions of the parabrachial nucleus and conditioned taste aversion: further evidence for an associative deficit in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:160–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reilly S, Grigson PS, Norgren R. Parabrachial nucleus lesions and conditioned taste aversion: evidence supporting an associative deficit. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:1005–17. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feigin MB, Sclafani A, Sunday SR. Species differences in polysaccharide and sugar taste preferences. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1987;11:231–40. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(87)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sclafani A, Nissenbaum JW. Taste preference thresholds for Polycose, maltose, and sucrose in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1987;11:181–5. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(87)80024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehnberg BG, MacKinnon BI, Hettinger TP, Frank ME. Analysis of polysaccharide taste in hamsters: behavioral and neural studies. Physiol Behav. 1996;59:505–16. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ader R. Conditioned taste aversions and immunopharmacology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;443:293–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb27080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scalera G, Spector AC, Norgren R. Excitotoxic lesions of the parabrachial nuclei prevent conditioned taste aversions and sodium appetite in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1995;109:997–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development. 1992;116:201–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jongen-Rêlo AL, Feldon J. Specific neuronal protein: a new tool for histological evaluation of excitotoxic lesions. Physiol Behav. 2002;76:449–56. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hajnal A, Norgren R. Taste pathways that mediate accumbens dopamine release by sapid sucrose. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:363–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norgren R, Pfaffmann C. The pontine taste area in the rat. Brain Res. 1975;91:99–117. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grigson PS, Shimura T, Norgren R. Brainstem lesions and gustatory function: III. The role of the nucleus of the solitary tract and the parabrachial nucleus in retention of a conditioned taste aversion in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:180–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cubero I, Lopez M, Navarro M, Puerto A. Lateral parabrachial lesions impair taste aversion learning induced by blood-borne visceral stimuli. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;69:157–63. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson GL, Berl T. Pathophysiology of water. In: Brenner BM, Rector FC, editors. The kidney, 4th ed., vol. 1. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1991. p. 677–736.

- 25.Bode U, Seif SM, Levine AS. Studies on the antidiuretic effect of cyclophosphamide: vasopressin release and sodium excretion. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1980;8:295–303. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950080312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell DM, Atkinson A, Gillis D, Sochett EB. Cyclophosphamide and water retention: mechanism revisited. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000;13:673–5. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2000.13.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menani JV, De Luca LA, Jr, Johnson AK. Lateral parabrachial nucleus serotonergic mechanisms and salt appetite induced by sodium depletion. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R555–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.2.r555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards GL, Johnson AK. Enhanced drinking after excitotoxic lesions of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R1039–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.4.R1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peck JH, Ader R. Illness-induced taste aversion under states of deprivation and satiation. Anim Learn Behav. 1974;2:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seeley RJ, Blake K, Rushing PA, Benoit SC, Eng J, Woods SC, et al. The role of CNS GLP-1-(7-36) amide receptors in mediating the visceral illness effects of lithium chloride. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1616–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01616.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernstein IL. Taste aversion learning: a contemporary perspective. Nutrition. 1999;15:229–34. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(98)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Logue AW, Ophir I, Strauss KE. The acquisition of taste aversions in humans. Behav Res Ther. 1981;19:319–33. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(81)90053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norgren R. Projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract in the rat. Neuroscience. 1978;3:207–18. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(78)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grill HJ, Norgren R. Chronic decerebrate rats demonstrate satiation but not bait shyness. Science. 1978;201:267–9. doi: 10.1126/science.663655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ader R, Cohen N. Conditioning and immunity. In: Ader R, Felten DL, Cohen N, editors. Psychoneuroimmunology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. p. 3–34.