Abstract

South Korea is one of the world’s most rapidly industrializing countries. Along with industrialization has come universal health insurance. Within the span of 12 years, South Korea went from private voluntary health insurance to government-mandated universal coverage.

Since 1997, with the intervention of the International Monetary Fund, Korean national health insurance (NHI) has experienced deficits and disruption. However, there are lessons to be drawn for the United States from the Korean NHI experience.

SOUTH KOREA ACHIEVED universal health insurance in 12 years. This remarkable achievement started modestly in 1977 when the government mandated medical insurance for employees and their dependents in large firms with more than 500 employees. In 1989, national health insurance (NHI) was extended to the whole nation. Most Western analysts were surprised. Many predicted Korean NHI would falter financially, but trends in financial receipts and disbursements from 1990 to 1995 showed no sign of financial instability. Everything went smoothly in both administration and financing in the first half of the 1990s. However, with the advent of the economic crisis of 1997 throughout southeast Asia, Korean NHI began to run a financial deficit. At the end of 1997, despite some Korean resistance, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) intervened in Korean financial affairs, causing a dramatic increase in the NHI’s deficit, which then grew each year until 2002.

When the government announced that NHI would separate reimbursement for pharmaceuticals from medical care in July of 2000, Westernized medical practitioners closed their clinics and refused to treat patients. This policy of separating reimbursement for pharmaceuticals from medical care is regarded as the most significant factor in disrupting the financial structure of Korean NHI.

NATIONAL MEDICAL INSURANCE IN KOREA

How did Korea succeed in providing health insurance to the whole nation within 12 years? Before 1977, Korea had only voluntary health insurance. In 1977, President Park Chung-Hee and the legislature passed a law that mandated medical insurance for employees and their dependents in large firms with more than 500 employees (Table 1 ▶). Gradually health insurance coverage was expanded to different groups in the society: in 1979 to government employees, private school teachers, and industrial workplaces with more than 300 employees, and in 1981 to industrial workplaces with more than 100 employees. In the late 1980s, health insurance expansion became regionally based, first to rural residents in 1988 and then to urban residents in 1989. Each of these expansions was mandated by government.

TABLE 1—

A Chronology of Events in South Korean National Health Insurance

| Year | Main action |

| 1963 | Medical insurance law enacted permitting voluntary health insurance |

| 1977 | Medical insurance for employees and their dependents in large firms (more than 500 employees) is mandatory |

| 1979 | Medical insurance for government employees and private school teachers and employees is mandatory |

| 1979 | Medical insurance for industrial workplaces with more than 300 employees is mandatory |

| 1981 | Medical insurance for industrial workplaces with more than 100 employees is mandatory |

| 1981 | Regional medical insurance of 3 geographic areas is implemented on a demonstration basis |

| 1988 | Regional medical insurance for rural residents is mandatory |

| 1989 | Regional medical insurance for urban residents becomes mandatory |

| 1997 | Regional medical insurance societies and medical insurance societies for government employees and private school teachers and employees are merged organizationally (not financially) into one society |

| 1999 | The Unified Health Insurance Act is implemented |

Clearly, South Korea had adopted Japan’s health insurance system as a model. Given the overall impact of the Japanese model of industrialization on the socioeconomic development of Korea, it is not surprising that the Japanese health insurance system became a prototype for Korean NHI. This in spite of the fact that American medicine had a dominant influence on the development of Korean medicine after 1945. However, the American model was not an ideal model for the Korean health insurance system because the United States had failed to achieve compulsory, universal health insurance.

The Japanese model’s influence in shaping Korean health insurance was most notable in 3 areas: (1) the administrative structure of the system, (2) the choice about who would be covered, and (3) the policy for mobilizing financial resources for the system. While Japanese health insurance was a dual system in the 1970s, consisting of employer- and employee-financed health insurance and governmentsponsored NHI, at the outset Korea adopted only the former scheme of employer–employee health insurance in firms with more than 500 employees. According to the legislation, as in the Japanese model, the employer and the employee each paid half the premium. There was some government subsidy, not for the beneficiary but for the operating budgets of “medical insurance societies.” Premiums were determined by multiplying the standard monthly salary by the health insurance contribution rate, which ranged from 3% to 8% of wages.

The insurers, as the agents in charge of managing the program, consisted of 2 types of medical insurance societies. The class 1 medical insurance society was made up of the employers and class 1 employees. The class 2 medical insurance society consisted of any resident within regional jurisdiction of the medical insurance society who wanted to join. To provide health insurance for the uninsured, the minister of health and social affairs could order a medical insurance society to join the Central Federation of Medical Insurance Societies (CFMIS). The major role of CFMIS was to ensure stable insurance financing and to manage medical and welfare institutions. Both medical insurance societies and the CFMIS were regulated by the rules established in civil law.

Why did the Park government choose the medical insurance society as the administrative organ responsible for implementing NHI? What are the policy implications for the country of this choice? The issue of whether or not to have a decentralized medical insurance society–based administrative system has been a hotly debated policy issue in Korea. Several factors favored the choice of decentralized administration, implicit in the organization of medical insurance societies.

First, this was essentially the structure of the Japanese health insurance system. Second, the Park government considered the decentralized health insurance system as an intermediate step between a completely private voluntary health insurance system (e.g., health maintenance organizations) that would emphasize cost containment and a state-administered health insurance system (e.g., single-payer NHI) that might place substantial financial burdens on the state. Third, the bureaucratic machinery to administer an NHI system just did not exist within the Korean government in 1977, when President Park decided to mandate health insurance for large employers. Therefore, medical insurance societies appeared to be the best vehicle for gradually extending health insurance to the whole nation.

THE ARITHMETIC OF HEALTH CARE REFORM

Since 1977, when the Park government endorsed decentralized medical insurance societies, there has been a continual political and policy struggle between those favoring unification of the medical insurance societies under a national system and those opposed to unification, preferring decentralization without government regulation. This struggle has shaped the unique development of the Korean national health care system.

The battleground between those for medical insurance unification and those against it has encompassed 3 policy debates. The first debate focuses on the reduction of income inequality between rich and poor. Those for unification insist that unification will reduce the income disparities that exist between industrial employees and the self-employed. Those for decentralization argue that unification will result in transferring insurance premiums paid by industrial employers and their employees to the selfemployed, whose premiums are inadequate to cover their expenses. While those for unification argue that unification will help create a spirit of solidarity among all classes of workers, resembling the foundation of the Western welfare state, those for decentralization believe that unification scheme will result in a “Korean unique case,” organizationally incompatible with the decentralized administrative model of NHI developed by the Japanese, French, and Germans.

The second policy debate centers around the issue of government financial assistance to the NHI system. Kim Dae-Jung, once a political prisoner and then a Nobel Peace Laureate, when he became Korea’s president, used the issue of NHI administration to consolidate his power. President Kim chose unification not because he agreed with its policy objectives, but because he felt that it would more effectively empower the political base of his government. However, in spite of the Kim administration’s initial promise to financially back 50% of the total expenditures of regional health insurance, ultimately the government decided to limit its contribution to $700 million.

The third policy debate involves how to equitably impose insurance premiums on the workforce throughout the nation. Korean workers are represented by 2 different labor organizations, which take opposite positions in this debate. The Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, representing the progressive wing of the labor movement, is strongly opposed to decentralization. The Federation of Korean Trade Unions endorses decentralization, declaring that the insurance premiums paid by employees should not be pooled (centralized) with the insurance premiums paid by the self-employed. The Federation of Korean Trade Unions argues that an equitable health insurance premium “tax” on all workers is impossible because 53% of the self-employed do not pay any income tax.

THE FINANCIAL CRISIS IN KOREAN HEALTH CARE

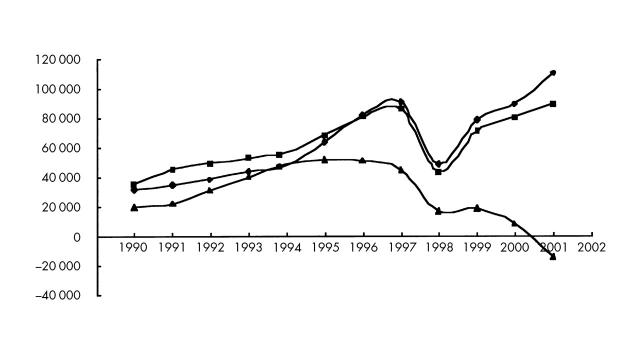

After 1996, Korean NHI began to develop significant deficits (Figure 1 ▶). From 1996 to the present, total health expenditures have exceeded total income. During the economic crisis of 1997, when the Korean economy was controlled by the IMF, NHI’s financial deficit grew worse. In addition, the financial structure of Korean NHI was disrupted by the separation of reimbursement for medical care and reimbursement for pharmaceutical services in July 2000. Although government continually raised the mandatory insurance premiums to make up for the deficit, many health policy experts predicted that increased governmental funding would not solve the problem.

FIGURE 1—

Trends in financial receipts and disbursements of Korean national health insurance.

Source. Data from Choi.1

Note.Numbers on the y-axis represent thousands of US dollars. Diamonds represent total disbursements; squares, total receipts; triangles, total reserve.

Korean NHI has been unable to control health care expenditures.2,3 The Korean government, on the one hand, has assumed exclusive control over medical care financing without including the medical profession in the policymaking process. Organized medicine has complained that only 65% of customary medical care costs are reimbursed by current health insurance. Korean physicians blame the government, claiming that it has developed a universal health insurance system at the expense of their professional incomes and autonomy.4

Korean medical professionals, on the other hand, have practiced without any public accountability. Government has never tried to intervene in the clinical autonomy of medical doctors. These laissez-faire practices have resulted in some appalling health care statistics—excessive overuse of antibiotics, more magnetic resonance imaging machines per million population than anywhere else in the world, and cesarean delivery rates of about 40% of live births.5

While the Korean government has begun to show interest in controlling health insurance costs, it has done little public monitoring and regulating of health care services provided by doctors and pharmacists. As a result of this unbalanced governmental approach, the Korean people have been exposed to excessive and sometimes harmful health services.

This structural problem derives from 3 interrelated weaknesses in the Korean health care system. First, medical specialists make up more than 80% of practicing medical doctors in Korea. In addition, one fourth of Korean medical doctors have 2 or more specialties. In most Western industrialized countries, medical specialists constitute no more than 50% of all practicing physicians. Korean medical care costs have escalated because medical specialists generate high-tech, expensive tests and treatments in highly commercialized university hospitals. This, in turn, has exacerbated the financial deficit of NHI. The Korean government has developed no policy tools with which to discourage Korean medical doctors from becoming specialists.

Second, the private medical care sector currently consumes about 90% of total health care resources, particularly in terms of hospital beds. Korean governments have had little interest in expanding the public health care delivery sector, except for community public health centers known as Bogeunso. The other publicly owned institutions are the National Medical Center, built by the US Army during the Korean War in 1950, and provincial medical centers built by Japanese colonizers. These public institutions provide only 10% of total health care services. Almost all the rest of Korean health care facilities are for-profit. This private sector–dominated health care system is another stimulus for the increased use of highly expensive medical care.6As in the case of the oversupply of medical specialists, the Korean government has not been able to formulate any policy alternatives to the private sector–dominated delivery system.

Third, pharmaceutical expenditures have consumed about 30% of total health expenditures. Before the policy of separating medical care reimbursement from pharmaceutical reimbursement was implemented in July 2000, Korean pharmacists were free to sell antibiotics and other potent biomedical drugs to customers without a doctor’s prescription. Government has never prevented pharmacists from serving as primary health care practitioners. This factor has contributed to NHI’s financial crisis. To make matters worse, shortly after the separation policy was implemented, pharmaceutical expenditures began to rise rapidly because of the intense lobbying by multinational pharmaceutical companies to allow marketing of high-cost drugs. When the minister of health and welfare was replaced in July 2002, he blamed the government for playing into the hands of the multinational pharmaceutical industry.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REFORM IN THE UNITED STATES

The United States can learn 4 lessons from the Korean experience with health care reform. The first centers on the question, Is decentralization or unification more desirable for the initiation of an NHI program in the United States? In Korea, neither of these 2 administrative systems has proven to be more efficient and effective than the other. Progressive policy experts and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) insist that unification is logically preferable. However, even in a small country such as Korea, there have been serious problems after unification. Given the larger size of the United States, in both population and geography, it will be even more difficult to launch a unified administrative system in the United States.

The second lesson focuses on the newly recognized role of governmental policies in regulating the supply side of the market. Cost containment–centered government policies had worked effectively in Korea for 20 years until the IMF intervened in 1997. The Korean case shows that governmental cost containment in the absence of enhanced capacities for regulating the supply side of the market is no longer effective in controlling health care expenditures.

Korea’s success in developing NHI over 2 decades can be attributed to this policy of tightened cost controls by government. However, the Korean government failed to recognize the significance of the supply-side aspects of cost containment in maintaining the financial stability of NHI. The following examples of government failure to regulate the supply side of the market have resulted in excessively high health care expenditures in both Korea and the United States: (1) a laissez-faire approach to practices by medical specialists, (2) private sector–centered hospitals and clinics’ overuse of high medical technology, and (3) multinational pharmaceutical enterprises’ campaigns promoting the use of expensive antibiotics and other drugs. Without successful regulation on the supply side, little financial stability in health insurance is possible, whether the insurance is nationalized or private.

The third lesson emphasizes the balance of power between the state and civil society. In Pharmacracy, Thomas Szasz writes, “The United States is the only country explicitly founded on the principle that, in the inevitable contest between the private and public realms, the scope of the former should be wider than that of the latter.”7(pXXX) If the United States wants to establish any public system such as an NHI program, the state must, first of all, transform the current private-centered health care system into a public-centered one.

The last lesson stresses the role of NGOs. Many Korean NGOs, including progressive labor unions and health care–related professional organizations, aggressively called for government intervention in health care reform in response to the failure to regulate the supply side of the market. They asserted that market-driven health care reform in Korea weakened the financial structure of NHI.8As Beauchamp argues in Health Care Reform and the Battle for the Body Politic, “the purpose of reform is not simply to solve the health care crisis, but also to reconstruct the disorganized public.”9(p41) Given the strong interest-group influence, NGOs remain the only sector that can empower the public to demand a financially stable national health program, in Korea as well as in the United States. Furthermore, Korean and American NGOs should share their experiences in health care reform in order to strengthen their unique position in the health care system, independent of both governmental dominance and medical professional autonomy.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Choi BH. Financial crisis and policy agenda of health security [in Korean]. In: Proceedings of the 2001 Annual Meeting, Korean Social Security Association. 2001:7–59.

- 2.Anderson GF. Universal health care coverage in Korea. Health Aff (Millwood). 1989;8(2)24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peabody JW, Lee SW, Bickel SR. Health for all in the Republic of Korea: one country’s experience with implementing universal health care. Health Policy. 1995;31:29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JC, ed. Great Debates on Health Care in Korea [in Korean]. Seoul, Republic of Korea: Sonamu; 2000.

- 5.Kim BY. Korean experiment for the unification of multiple medical insurers: a road to success or failure. In: International Symposium on National Health Insurance, Korea Health and Welfare Forum. 2000:3–39.

- 6.Flynn ML, Chung YS. Health care financing in Korea: private market dilemmas for a developing nation. J Public Health Policy. 1990;11(2):238–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szasz T. Pharmacracy: Medicine and Politics in America. Westport, Conn: Praeger Publishers; 2001.

- 8.Cho BH. The role of NGOs in the process of health care reform [in Korean]. Health Social Sci. 2001;10:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beauchamp DE. Health Care Reform and the Battle for the Body Politic. Philadelphia, Pa: Temple University Press; 1996.