Abstract

Violence is a public health problem that can be understood and changed. Research over the past 2 decades has demonstrated that violence can be prevented and that, in some cases, prevention programs are more cost-effective than other policy options such as incarceration.

The United States has much to contribute to—and stands to gain much from—global efforts to prevent violence. A new World Health Organization initiative presents an opportunity for the United States to work with other nations to find cost-effective ways of preventing violence and reducing its enormous costs.

ON OCTOBER 3, 2002, THE World Health Organization (WHO) released the milestone World Report on Violence and Health.1 This report examines what is known about the epidemiology and prevention of violence from research and programs throughout the world. It addresses several types of violence, including child abuse and neglect by caregivers, youth violence (violence by adolescents and young adults aged 10 to 29 years), intimate partner violence, sexual violence, elder abuse, self-inflicted violence, and collective violence (the use of violence by one group against another to achieve political, social, or economic objectives; for example, war or terrorism). The report discusses how the different types of violence are related and also contains recommendations for advancing efforts to prevent violence at the global, national, and local levels. The report is the result of 3 years of work, during which WHO drew on the knowledge of more than 160 experts from more than 70 countries.

The release of this report marks the beginning of a worldwide WHO campaign that will include global and national events with decisionmakers, the media, and the general public. The campaign will focus on discussing how the report’s recommendations might be implemented. As we embark on this global campaign, it is useful for the US public health community to consider its role in global efforts to prevent violence.

VIOLENCE IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT

On an average day more than 4500 people worldwide die violent deaths (i.e., those related to suicide, homicide, and war).1 About half of the estimated 1.7 million violent deaths that occurred in the world in 2000 were the result of suicide, about one-third resulted from homicide, and one-fifth were from warrelated injuries (Table 1 ▶).

TABLE 1.

—Estimated Global Violence-Related Deaths, 2000

| Type of Violence | Numbera | Age Adjusted Rate per 100 000 Population | Proportion of Total (%) |

| Homicide | 520 000 | 8.8 | 31.3 |

| Suicide | 815 000 | 14.5 | 49.1 |

| War-related | 310 000 | 5.2 | 18.6 |

| Totalb | 1 659 000 | 28.8 | 100.0 |

| Country income level | |||

| Low to middle | 1 510 000 | 32.1 | 91.1 |

| High | 149 000 | 14.4 | 8.9 |

Note. Data are from the WHO Global Burden of Disease Project for 2000, Version 1.

aRounded to the nearest 1000.

bIncludes 14 000 intentional injury deaths resulting from legal intervention. Consequently the numbers, rates, and percentages in this table do not add up to the exact figures in the total row.

Violence disproportionately impacts adolescents and young adults. Suicide, interpersonal violence, and war-related deaths are the 4th, 5th, and 10th leading causes of death, respectively, among 15- to 44-year-olds in the world. Together, they account for about 13.6% of deaths among males and 7.1% of deaths among females in this age group, although rates vary considerably by region, country, and areas within countries.

The United States has very high rates of homicide- and firearmrelated death, compared with other high-income countries throughout the world.2–4 The US violent death rate in 2000 was about twice as high as the estimated rate for other high-income countries in 2000.1 However, when one considers the entire world, many nations and regions face far higher rates of violent death than the United States.5

The US age-adjusted homicide rate of 6.2 per 100 000 in 2000 was lower than the global estimated rate of 8.8 per 100 000.1,6 Moreover, estimated homicide rates for the WHO regions of Africa and the Americas were about 3 times those for the United States. Similarly, the US age-adjusted suicide rate of 10.6 per 100 000 in 2000 was lower than the global estimated suicide rate of 14.5 per 100 000.1,6 Estimated suicide rates for 2000 in the WHO regions of Europe and the Western Pacific were about twice those of the United States. In 2000, the United States suffered very few war-related deaths, in contrast to the African region, where more than half of the world’s estimated 310 000 war-related deaths occurred that year and where war-related deaths outnumber homicides and suicides.

Although the United States fares better than most of the world in the absolute rate of violent death, homicide and suicide are relatively more important as causes of death in the United States than in many other parts of the world. Throughout the world, suicide is estimated to have been the 13th leading cause of death in 2000 and homicide the 22nd leading cause.1 In contrast, in the United States suicide was the 11th leading cause of death and homicide the 14th in 2000.6

Fatal injuries represent only a small fraction of the health burden of violence. Nonfatal violence between intimate partners, for example, compromises the health of millions of women throughout the world. Population-based studies conducted in 48 countries have revealed that 10% to 69% of women report having been physically assaulted by an intimate partner during their lifetimes.7 In the United States, this figure is 22.1%.8 In cities that have conducted population-based studies, the proportion of women reporting an attempted or completed sexual assault by an intimate partner sometime during their lifetime ranges from 6.2% in Yokohama, Japan, to 46.7% in Cuzco, Peru.9 The lifetime prevalence in the United States is 7.7%.8 The percentage of female adolescents reporting that their first sexual intercourse was forced ranges from 7% in New Zealand to 47.6% in a 9-country study in the Caribbean.9 In the United States, this prevalence is reported to be 9.1%.9

Maltreatment has a severe impact on the health of children and the elderly. Limited research has shown that in some countries nearly half of children report they have been hit, kicked, or beaten by their parents,10 and about 20% of women and 5% to 10% of men report having suffered sexual abuse as children.11,12 Furthermore, 4% to 6% of the elderly have experienced some form of abuse in their homes in the previous year.13–17 These estimates are based largely on studies conducted in the United States and other developed countries.

Youth violence, suicidal behavior, and war also have significant consequences for the morbidity of many populations around the world. The proportion of 13-year-olds that report engaging in bullying once a week ranges from 1.2% in England and Sweden to 9.7% in Latvia.18 The comparable US proportion is 7.6%.18 The ratio of fatal to nonfatal suicidal behavior in the United States is estimated to be approximately 1:2–3 among persons over age 65; among people under age 25, the ratio may reach 1:100–200.19,20 These findings are comparable to parts of the developed world, but data for less developed countries are not readily available. And, although the exact figures may never be determined, huge numbers of people—very often women and children—suffer injuries and permanent disability as a result of wars and other forms of collective violence in many parts of the world.21

The health and social consequences of violence are much broader, however, than death and injury. They include very serious consequences for the physical and mental health and development of victims. Studies indicate that exposure to maltreatment and other forms of violence during childhood is associated with risk factors and risk-taking behaviors later in life (depression, smoking, obesity, high-risk sexual behaviors, unintended pregnancy, alcohol and drug use) as well as some of the leading causes of death, disease, and disability (heart disease, cancer, suicide, sexually transmitted diseases).22–30

In many nations and communities, violence and war also increase the costs of services related to health and security, thereby reducing productivity and property values, disrupting human services, and undermining governance. Between 1996 and 1997, the Inter-American Development Bank sponsored studies on the economic impact of collective and interpersonal violence in 6 Latin American countries. Expenditures just for health services related to such violence amounted to about 1.9% of the gross domestic product in Brazil, 5% in Colombia, 4.3% in El Salvador, 1.3% in Mexico, 1.5% in Peru, and 0.3% in Venezuela.31 The threat of interpersonal violence and war destabilizes the economies of nations and regions by threatening the establishment and viability of businesses and, hence, the prospects for economic growth.

LEARNING FROM THE REST OF THE WORLD

Increasingly, violence is becoming a global problem. This is clearly the case in wars and other forms of collective violence that frequently transcend geographic and physical boundaries. Interpersonal violence and suicidal behavior also can cross international borders. Recent immigrants, for example, may bring cultural values or norms that make them more or less vulnerable to interpersonal violence or suicidal behavior than people who were born in the United States or who have lived there for many years.

Even where violence itself does not cross borders, some factors that influence it do. For example, illicit drug markets may be accompanied by violence in countries involved in the production, distribution, and sale of illegal drugs.32 Industries such as small arms trade and sexual slavery also have implications that transcend national borders.33–35 Other issues that may be more difficult to assess but are cause for concern include increased penetration of global media markets by violent programming and, in some cases, the apparent glorification of violence in sports and computer games.18

One important insight gained from looking at violence as a global problem is the importance of cultural context. Cultural tradition is sometimes used to justify social practices that perpetrate violence.1 Such practices include violence against women, female genital mutilation, and the use of severe physical means to punish children, including at school.

Cultural norms must be dealt with sensitively and respectfully in all research and prevention efforts—sensitively, because of people’s often passionate attachment to their traditions, and respectfully, because culture is often a source of protection against violence (for example, long-held traditions may promote equality of women or respect for the elderly). Prevention programs as well as mechanisms for promoting them must be tailored to their target populations. The United States will need to increase its understanding of its own cultural diversity in order to improve efforts at preventing violence domestically.

Cross-national studies show that the quality of a government—as reflected in the efficiency and reliability of its criminal justice institutions and the existence of programs that provide economic safety nets—is associated with lower rates of homicide.36–38 In Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, for example, one study concluded that dissatisfaction with the police, the justice system, and prisons increased the use of unofficial modes of justice.39 In the United States, these institutions are often taken for granted, but in examining the problem of violence globally, one becomes increasingly aware that these institutions are the first line of defense against higher rates of interpersonal and collective violence. From the perspective of violence prevention, maintaining a fair and efficient criminal justice system and basic supports for individuals and families in dire economic circumstances should remain an important priority in the United States.

In examining preventive responses to violence around the world, one is struck by the nature and resourcefulness of many of the strategies adopted in lowincome communities. For example, in some communities in India, the practice of dharna—public shaming and protest done in front of the house or workplace of abusive men—has been used as a strategy to prevent the recurrence of intimate partner violence.40 And in the Kapchorwa district of Uganda, the Reproductive, Education, and Community Health Program enlists the support of elders in incorporating alternative practices to female genital mutilation that uphold the original cultural traditions.41 Although the effectiveness of these approaches has yet to be definitively demonstrated, they are inexpensive and build on the unique nature of the communities in which they were implemented—something that is needed in low-income US communities as well, where violence is more common and prevention resources scarce.

One risk factor that appears to be universally associated with interpersonal and collective violence is income inequality.36,42 Poverty itself does not appear to be consistently associated with violence, but the juxtaposition of extreme poverty with extreme wealth appears to be a key ingredient in the recipe for violence. Given that income inequality has been growing in recent decades in many wealthy countries, it may be wise to closely examine its potential contribution to higher rates of violence in the United States and be more proactive in finding strategies to reduce its influence on violence.

CONTRIBUTING TO PREVENTION WORLDWIDE

The United States can contribute significantly to preventing violence worldwide. For example, US research-funding institutions can continue to invest in research to better understand the etiology and prevention of violence. This research investment should be extended to include cross-cultural and international research, especially on the social, economic, and policy factors that transcend national borders.

The lessons learned from US progress in building violence prevention programs at the federal and state levels can help other countries establish their own programs. Violence prevention work within the Department of Health and Human Services has greatly expanded over the past 20 years. Twenty years ago, for example, fewer than 5 people worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on violence as a public health problem. Now the CDC has more than 70 people working full-time on violence prevention in its Division of Violence Prevention within the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, making this the largest organized collection of experts in the world fully devoted to preventing injuries and deaths associated with violence. The division budget has grown from less than $500 000 to more than $90 million during this time.

The field of violence prevention has grown in the United States along with the CDC’s program. Two decades ago, few, if any, state or local health departments had activities addressing violence. US public health schools did not teach their students about violence prevention, and scientific articles about violence did not appear in leading medical and public health journals. Today, most US state and large city health departments have some activities focused on violence prevention. Almost every school of public health in the United States has added courses on the epidemiology of violence and its prevention or has at least integrated this issue into its existing coursework. And scientific articles on violence are regularly seen in leading journals.

The concepts, principles, and methods underlying the growth of the field of violence prevention in the United States may also be useful in establishing violence prevention programs in other countries. US public health institutions and foundations can also help stimulate and support the development of international organizations that will in turn advance evidence-based violence prevention policies and programs in other parts of the world and help nations learn from one another.

Finally, the United States should consider its role, direct or indirect, in influencing conditions that contribute to violent political conflict in many parts of the world. The United States should similarly consider how it influences globalization patterns that are associated with violence.

CONCLUSION

Twenty year ago, the words “violence” and “prevention” were rarely used in the same sentence. Today, the idea that violence can be prevented is more widely recognized, thanks to the traditions and concepts of public health: a commitment to prevention, the application of the tools of science to achieve this goal, and the firm belief that effective public health actions require collaboration and cooperation across scientific disciplines, civic organizations, societal sectors, and political entities at all levels. The application of these traditions and concepts to violence is inspiring policymakers, advocates, civic leaders, youth, students, researchers, teachers, and others in many parts of the world to take actions they may have never previously contemplated to reduce the profound physical and psychological consequences of violence.

Violence is a problem that can be understood and changed, not an inevitable consequence of the human condition. The United States has much to gain from and to contribute to global efforts to prevent violence. Policymakers and the public health community in the United States should embrace this opportunity to contribute to improving the health and quality of life of people throughout the world through violence prevention.

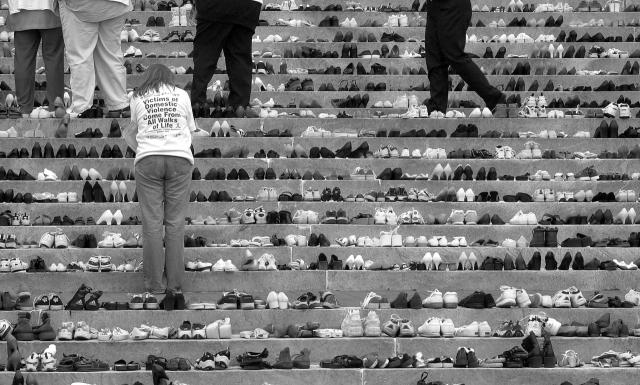

Figure 1.

A woman stands amid hundreds of pairs of shoes placed on the steps of the Kentucky state capitol on October 15, 2002, to bring attention to victims of domestic violence. Last year, Kentucky's 17 domestic violence programs sheltered more than 4600 women and children, according to officials. (AP Photo/Ed Reinke)

Figure 2.

A sculpture of a gun with a tied-up barrel, symbolizing a gun-free South Africa, is seen at the entrance to the Victoria and Albert waterfront shopping center in Cape Town, South Africa, in 1999. The government unveiled stringent new gun control legislation that year. The law stiffens sentences, obliges gun owners to reregister firearms every five years, and gives police more powers to investigate suspected owners of illegal weapons. (AP Photo/Obed Zilwa)

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, eds. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002.

- 2.Fingerhut L, Kleinman JC. International and interstate comparisons of homicide among young males. JAMA. 1990;263:3292–3295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Powell KE. Firearm- and non-firearm-related homicide among children: an international comparison. Homicide Stud. 1998;2(1):83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krug EG, Powell KE, Dahlberg LL. Firearm-related deaths in the United States and 35 other high- and upper-middle-income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reza A, Mercy JA, Krug E. Epidemiology of violent deaths in the world. Inj Prev. 2001;7:104–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars. Accessed November 1, 2002.

- 7.Heise L, Garcia-Moreno C. Violence by intimate partners. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, eds. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002:87–121.

- 8.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000. Publication No. NCJ 183781.

- 9.Jewkes R, Sen P, Garcia-Moreno C. Sexual violence. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, eds. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002:147–181.

- 10.Hahm HC, Guterman NB. The emerging problem of physical child abuse in South Korea. Child Maltreatment. 2001;6:169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelhor D. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Neglect. 1994;18:409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelhor D. Current information on the scope and nature of child sexual abuse. Future Children. 1994;4:31–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pillemer K, Finkelhor D. The prevalence of elder abuse: a random sample survey. Gerontologist. 1988;28:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Podnieks E. National survey on abuse of the elderly in Canada. J Elder Abuse Neglect. 1992;4:5–58. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivelä SL, Kongas-Saviaro P, Kesti E, Pahkala K, Ijas ML. Abuse in old age: epidemiological data from Finland. J Elder Abuse Neglect. 1992;4:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogg J, Bennett GCJ. Elder abuse in Britain. BMJ. 1992;305(6860):998–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Comijs HC, Pot AM, Smit JH, Bouter LM, Jonker C. Elder abuse in the community: prevalence and consequences. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:885–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercy JA, Butchart A. Farrington D, Cerda M. Youth violence. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, eds. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002:23–56.

- 19.McIntire MS, Angle CR. The taxonomy of suicide and self-poisoning: a pediatric perspective. In: Wells CF, Stuart IR, eds. Self-Destructive Behavior in Children and Adolescents. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1981:224–249.

- 20.McIntosh JL, Santos JF, Hubbard RW, Overholser JC. Elder Suicide: Research, Theory and Treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1994.

- 21.Zwi AB, Garfield R, Loretti A. Collective violence. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, eds. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002:213–239.

- 22.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999;282:1652–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dietz PM, Spitz AM, Anda RF, et al. Unintended pregnancy among adult women exposed to abuse or household dysfunction during their childhood. JAMA. 1999;282:1359–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: a retrospective study. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addict Behav. 2002;27:713–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti VJ. Body weight and obesity in adults and selfreported abuse in childhood. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buvinic M, Morrison A. Technical Note 4: Violence as an Obstacle to Development. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank; 1999.

- 32.Briceño-León R, Zubillaga V. Violence and globalization in Latin America. Curr Sociol. 2002;50(1):19–37. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richard AO. International Trafficking in Women to the United States: A Contemporary Manifestation of Slavery and Organized Crime. Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Intelligence; 2000.

- 34.Boutwell J, Klare MT, Reed LW, eds. Lethal Commerce: The Global Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons. Cambridge, Mass: American Academy of Arts and Sciences; 1995.

- 35.Graduate Institute of International Studies. Small Arms Survey 2002: Counting the Human Cost. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002.

- 36.Fajnzylber P, Lederman D, Loayza N. Inequality and Violent Crime. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 1999.

- 37.Pampel FC, Gartner R. Age structure, socio-political institutions, and national homicide rates. Eur Sociol Rev. 1995;11:243–260. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Messner SF, Rosenfeld R. Political restraint of the market and levels of criminal homicide: a cross-national application of institutional-anomie theory. Soc Forces. 1997;75:1393–1416. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noronha CV, Machado EP, Tapparelli G, Cordeiro TR, Laranjeira DH, Santos CA. Violência, etnia e cor: um estudo dos diferenciais na região metropolitana de Salvador, Bahia, Brasil [Violence, ethnic group, and skin color: a study of disparities in the metropolitan region of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil]. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1999;5:268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitra N. Best Practices Among Response to Domestic Violence: A Study of Government and Non-Government Response in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women; 1999.

- 41.Reproductive health effects of gender-based violence. In: United Nations Population Fund. Annual Report 1998; 1998:20–21. Available at: http://www.unfpa.org/about/report/report98/ppgenderbased.htm. Accessed November 1, 2002.

- 42.Gartner R. The victims of homicide: a temporal and cross-national comparison. Am Sociol Rev. 1990;55:92–106. [Google Scholar]