Abstract

The history of health determinants in Canada influenced both the direction of data gathering about population health and government policies designed to improve health. Two competing movements marked these changes.

The idea of health promotion grew out of the 1974 Lalonde report, which recognized that determinants of health went beyond traditional public health and medical care, and argued for the importance of socioeconomic factors. Research on health inequalities was led by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research in the 1980s, which produced evidence of health inequalities along socioeconomic lines and argued for policy efforts in early child development.

Both movements have shaped current information gathering and the policies that have come to be labeled “population health.”

IN CANADA, THE NOTION OF determinants of health was derived from the work of Thomas McKeown, who influenced 2 somewhat different movements that together are now referred to as “population health.” Health promotion, the earlier of these movements, was first articulated by Hubert Laframboise in the widely circulated Lalonde report of 1974.1 The second, research focusing on inequalities in health, grew out of the efforts of Fraser Mustard and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.2 Both have had a strong effect on how health information is gathered and disseminated in Canada, but they have had a more limited influence on health policy. Here we attempt to describe these movements and their information and policy consequences.

McKeown was a professor of social medicine at the University of Birmingham in England during the establishment of Britain’s National Health Service. The service’s original promise of universal health care coverage to improve population health and eventually reduce demand on services was not fulfilled; increased access to medical services resulted in increased demand. McKeown argued that there were a large number of influences on health apart from traditional public health and medical services and that these influences should be considered in framing health policy and in any efforts to improve the health of the population.3

HEALTH PROMOTION

The Lalonde report marked the first stage of health promotion in Canada. It used McKeown’s ideas to develop a framework labeled “the health field concept” and applied this concept to an analysis of the then current state of health among Canadians. It concluded with a large number of health policy recommendations formulated in line with this new approach.

Determinants of Health

To the best of our knowledge, McKeown was the first to use the term “determinants of health.”4 The Lalonde report identified 4 major components of the health field concept: human biology, health care systems, environment, and lifestyle.1(pp31–34) In addition, it proposed health education and social marketing as the tools to persuade people to adopt healthier lifestyles.

Health promotion advocates quickly recognized that an excessive emphasis on lifestyle could lead to a “blame the victim” mentality. Smoking, for example, was not merely a matter of personal choice but also a function of one’s social environment. As a result, physical and social environments were differentiated, with growing emphasis placed on the latter. By 1996, as more distinctions and additions occurred, the 4 determinants of health described in the Lalonde report had grown to 12.5

The Lalonde report called attention to the existing fragmentation in terms of responsibility for health. “Under the Health Field Concept, the fragments are brought together into a unified whole which allows everyone to see the importance of all factors including those which are the responsibility of others.”1(pp33–34) The report was ahead of its time in identifying the need for intersectoral collaboration and recognizing that multiple interventions—a combination of research, health education, social marketing, community development, and legislative and healthy public policy approaches—are needed to properly address the determinants of health.

Policy Response

As did earlier movements, health promotion promised to prevent illness and reduce the ever-increasing demands for and costs of health care services: “If the incidence of sickness can be reduced by prevention then the cost of present services will go down, or at least the rate of increase will diminish.”1(p37) Governments, concerned by the escalating costs of health care, gratefully received and largely adopted the recommendations of the Lalonde report.6(p8) Table 1 ▶ presents a list of important dates in the development of health promotion in Canada.

TABLE 1—

Important Events in the Development of Health Promotion in Canada

| 1971 | Health Canada Long-Range Planning Branch established |

| 1974 | New Perspective on the Health of Canadians (the Lalonde report) published |

| 1978 | Health Promotion Directorate formed within Health Canada, which initiates a series of government policies to apply the recommendations of the Lalonde report |

| 1982 | Cabinet approves a permanent health promotion policy and program, resulting in specific initiatives dealing with, for example, tobacco, alcohol, drugs, and nutrition; developmental work in core programs, including school and workplace health, heart health, and child health; and establishment of a national health promotion survey |

| 1984 | “Beyond Health Care” conference sponsored by the Toronto Board of Health, the Canadian Public Health Association, and National Health and Welfare; 2 key health promotion concepts initiated: healthy public policy and the healthy city |

| 1986 | The Epp report, Achieving Health for All: A Framework for the Health of Canadians, is published |

| 1986 | The First International Conference on Health Promotion is held in Ottawa in collaboration with the World Health Organization and the Canadian Public Health Association; the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion is issued |

Information Systems

A graphic display of data about causes of death among Canadians by sex and age was included in the Lalonde report. This was a forerunner of the Report on the Health of Canadians.7 Later, Statistics Canada instituted risk factor surveys such as the National Population Health Survey, and the National Longitudinal Survey on Children and Youth was developed as well. The growing emphasis on wellness rather than disease led to the inclusion of such indicators as self-reported health status. The first large linked databases in Canada were established at the Manitoba Center for Health Policy in the early 1970s.

Comments

Multiple interventions in the area of Canadian health promotion, including public policies and legislation, had positive outcomes:

As a result of health education messages and restrictions on advertising, the national smoking rate dropped from approximately 50% to approximately 25%.8

New legislation increased the use of seat belts8 and bicycle and motorcycle helmets.9

Drunk driving decreased in response to both education efforts and stricter enforcement of laws prohibiting impaired driving.8

Diets changed; people began to consume less red meat, more fish, less fat, and more fruits and vegetables.8

Physical exercise increased in response to various healthpromoting publications (e.g., the Canada Food Guide10) and programs (e.g., the “Participaction” program,11 established by the government of Canada to support health priorities, particularly the promotion of healthy, active living, in unique and innovative ways).

During the late 1980s, the health promotion movement adopted a “settings” approach focused on improving health in schools, workplaces, and communities. “Empowerment” became a central concept in the promotion of good health. This approach emphasized processes more than outcomes, and while it enjoyed a certain degree of success (notably in the healthy communities and cities movements, which continue to function in some jurisdictions), the lack of measurable outcomes and means of evaluating program effectiveness attracted substantial criticism.

During the early 1990s, when increasing health care expenditures led governments to seek ways to cut health care spending, health promotion came under negative scrutiny. First, health promotion policies did not generate the anticipated savings in health care costs because new therapeutic and diagnostic technologies inexorably drove costs up. Second, health promotion messages were better received among the more advantaged sectors of society, and consequently inequities in certain risk behaviors (e.g., tobacco use8) actually worsened.

Third, other unexpected developments resulted in new problems. Although people exercised more, they also spent more time watching television and driving in vehicles, and while the nature of their diet improved, they ate more. Similarly, after an initial decline, smoking rates leveled off at about 25%.7 Finally, there was a growing perception that health promotion delivered inadequate “bang for the buck,” especially as certain programs (e.g., Participaction), after initial successes, failed to make continued improvements. Price Waterhouse was hired to evaluate the federal health promotion program in 1989. They drew the negative conclusion that “the paradigm which envisages health as the product of ‘anything and everything’ does not readily lend itself to being actioned.”12

INEQUALITIES IN HEALTH RESEARCH

Health inequities along social class lines have been an ongoing feature of epidemiological studies. Many health outcomes can be seen as gradients when they are plotted against an array of socioeconomic determinants; for example, in the 19th century Edwin Chadwick’s mortality tables indicated that child mortality could be correlated with paternal occupation level.13 In the case of cancer and heart disease, better health status has been closely correlated with socioeconomic variables.14

Similar to Laframboise and his staff, Fraser Mustard and researchers at CIAR were influenced by Thomas McKeown. McKeown had argued that health gains achieved in the 19th and 20th centuries were largely attributable to reduced family sizes and better nutrition. CIAR and others extended this analysis to identify social and economic factors that had powerful effects on the health of individuals and communities or nations.15

The authors of Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not?2 used epidemiological evidence to explain how different factors influence health, and they concluded that social and economic environments have a far stronger impact on health than individual behaviors. Several other studies reached similar conclusions.

The Whitehall study14,16 showed that the pronounced differences in disease incidence and mortality rates evident across income and social groups were caused not only by lifestyle and genetic makeup. The authors argued that decisionmaking power and control are important mediators of health inequalities.16

Economic development and the distribution of wealth in a society are important determinants of population health.17

Aspects of the workplace environment, both from a physical perspective and in terms of decisionmaking latitude (control), are important health determinants.14

Early development is extremely important in regard to a child’s future schooling, employment, and health.18 It is also critical in terms of the development of future coping skills.19

The term population health, introduced by Mustard and CIAR, was for some time the subject of debate. In the end, Health Canada and many provincial governments assumed the term for a large part of their health promotion activity, although the main emphasis was not on reducing inequalities in health. Recently, researchers focusing on health inequalities have attempted to incorporate many of the principles of health promotion, and population health is increasingly being used to refer to a more unified approach. These researchers argue that not all determinants of health are of equal importance; for instance, Marmot and others emphasize a subset of determinants that link such areas as control over work to health status.14

Policy Response

The health promotion movement stressed that intersectoral collaboration was necessary if policies were to deal with the many determinants of health. In Canada, there are initiatives that can be traced to these combined ideas regarding population health. Many of them have been initiated through the Canadian system of joint federal provincial/territorial committees.

All of the Canadian provinces have set health goals that encompass the varied determinants of health.20 Their objectives include improvements in working and living conditions, health behaviors, early child development, access to effective health care services, and aboriginal health.

All provinces with the exception of Ontario have regionalized the delivery of health services21 (a policy recommended in the Lalonde report) and focus more on addressing the broad determinants of health.5 Regional health care managers are engaging in intersectoral activities designed to address these determinants. As examples, Edmonton is working with the board of education to address obesity,22 and Montreal’s health department is collaborating with universities23 and municipal officials to translate research knowledge about child and family poverty into action.

Funding for research on population health has increased considerably. In 1999, the Canadian Population Health Initiative received $20 million to fund further research over a 4-year period. More recently, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research included population health as one of its 4 “pillars,” which also include biomedical, clinical, and health services research. Of the 13 institutes, 5 focus clearly on populationrelated areas: population and public health, aboriginal health, gender and health, aging and health, and child development. Human Resources Development Canada has provided $70 million to aid in assessing income supplementation for unemployed single parents through a randomized controlled social experiment.24

The child tax benefit illustrates the government’s recognition of the effects of poverty on children and families.25 The importance of early child development has been addressed through the Children’s Agenda, which attracted $2 billion in federal funding in 2000.26 Quebec has introduced a subsidized day care program with the specific objective of making professional early childhood education available to all children.27,28 Several jurisdictions are monitoring the adequacy of children’s early development by means of development indicators.29,30

Programs that have broadened their strategies to accommodate a population-based approach have experienced some success. An example is tobacco use reduction programs, which have incorporated restrictions on advertising, package warnings, restrictions on sales to minors, and restriction of smoking in public. The Canadian smoking rate has dropped to 20%, and rates are even lower in British Columbia and Ontario.31 Several academic institutions have responded to these positive changes by establishing institutes or centers for population health research.

Information Systems

Regular reports on population health and the determinants of health are now published at the regional, provincial, and national levels (e.g., the Capital Health annual report,32 the annual report on the health of British Columbians,33 the report on the health of Canadians,7 and the Maclean health reports34). In addition, several large, linked (and, in some cases, longitudinal) databases have been established nationally as well as in British Columbia, Manitoba, and Quebec, providing powerful sources for population health research. The Canadian Community Health Survey (formerly the National Population Health Survey) has been enhanced to provide more locally relevant data. The National Longitudinal Study on Children and Youth, funded by Human Resources Development Canada, is another important source of data for understanding population health and developing new policies. Finally, the Canadian Institute for Health Information, in partnership with Statistics Canada, has developed a population health indicators framework, as shown in Figure 1 ▶.

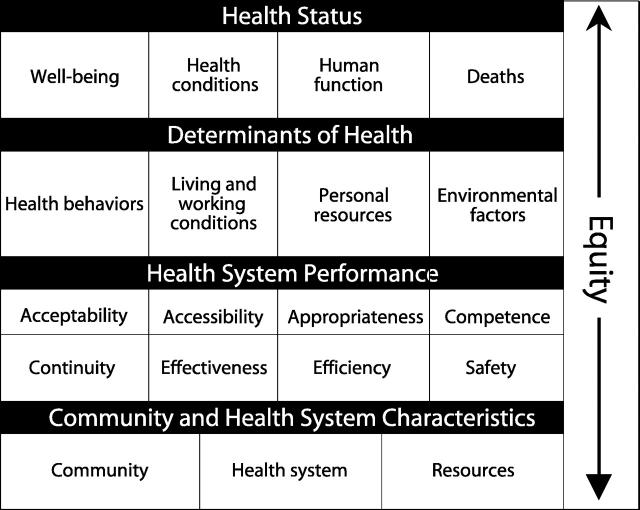

FIGURE 1—

Health indicators framework.

Note. The framework clusters 19 indicators into 4 categories, according to which data may be collected. This framework thus serves as a benchmark against which Canadian data collection practices can be measured. The degree of equity in a society is a characteristic of all indicators.

Data are now available to support some 80 to 90 indicators across all 4 domains of this framework and have been included in the Report on the Health of Canadians7 and in Health Care in Canada.21 These data, because they are standardized, support the development of reports on population health and the health care system across Canada at both the regional and provincial levels. They also allow for international comparisons of the health of the Canadian population and the performance of the Canadian health care system.

Comments

There is a great deal of interest, activity, and resources being deployed in pursuit of population health concepts. To some extent, this is due to the “bandwagon” effect that has surrounded the term population health. Despite several modest successes (e.g., in the areas of tobacco use and child development), however, the population health approach, while providing a deeper understanding of socioeconomic gradients in health status, has not yet resulted in adequate corresponding policy development to effectively reduce inequalities in health.

In the mid-1970s to mid-1980s, during the period of the Lalonde report and the Ottawa charter, Canada was among the countries leading the world in health promotion. Over the past decade, as the public dialogue has been dominated by concerns about the costs and delivery of health care services, inadequate attention has been paid to important emerging health issues, especially those that relate to inequalities. For example, family poverty, epidemic obesity, early childhood development, and aboriginal health are major health issues for which there is no coordinated national plan. In the meantime, countries such as the United Kingdom and Sweden have developed plans to address many of these issues and others such as teenage pregnancy, education, unemployment, access to health care, housing, and crime. These plans have been achieved through the involvement of other government departments such as education, justice, economic development, finance, housing, and social security.

Recently several Canadian health commissions35–38 have emphasized the importance of addressing the determinants of health and incorporating population health concepts and approaches into the health care system so as to improve the health of individuals and communities and reduce inequities. The Commission on the Future of Health Care38 will soon release its recommendations for improving the public health care system. This should clear the way for the public and policymakers to turn their attention toward some of the neglected health issues mentioned here. With effective political leadership, collaborative efforts between different sectors (government, the private sector, voluntary organizations), and the development of policies based on the best available evidence, Canada may once again join the countries leading the way in health promotion and population health.

S. Glouberman researched and wrote the sections on determinants of health and policy responses. J Millar wrote the sections on information systems. The authors collaborated on historical aspects and on the comments sections.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Lalonde M. A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Minister of Supply and Services; 1974.

- 2.Evans RG, Barer ML, Marmor TR, eds. Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not?: The Determinants of Health of Populations. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1994.

- 3.McKeown T. The Role of Medicine: Dream, Mirage or Nemesis? Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell; 1979.

- 4.McKeown T. An interpretation of the modern rise in population in Europe. Popul Stud. 1972;26:345–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nickoloff B, Health Canada. Towards a Common Understanding: Clarifying the Core Concepts of Population Health: A Discussion Paper. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Health Canada; 1996.

- 6.Glouberman S. Towards a New Perspective on Health Policy. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Policy Research Networks; 2001.

- 7.Report on the Health of Canadians. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Federal Provincial and Territorial Advisory Committee on Population Health; 1996.

- 8.Groff P, Goldberg S. The Health Field Concept Then and Now: Snapshots of Canada.; 2000.

- 9.Statistical Report on the Health of Canadians. Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada: Federal, Provincial and Territorial Advisory Committee on Population Health; 1999.

- 10.Canada’s Food Guide to Healthy Eating. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Health Canada; 1994.

- 11.Participaction: Our History and Evolution; 1971–. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Health Canada; 1989.

- 12.Discussion Paper on Phase I of a Study of Healthy Public Policy at Health and Welfare Canada. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Policy, Planning and Information Branch, Program Evaluation Division; 1992.

- 13.Chadwick E. Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. London, England: W Clowes; 1842.

- 14.Marmot MG, Bosma H, Heminway H, Brunner E, Stansfeld S. Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet. 1997;350:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKay L. Health Beyond Health Care: Twenty Five Years of Federal Health Policy Development. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Policy Research Networks; 2000.

- 16.Marmot MG, Kogevinas M, Elston MA. Social/economic status and disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 1987;8:111–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson RG. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. London, England: Routledge; 1996.

- 18.Jenkins J, Keating D. Risk and Resilience in Six and Ten Year-Old Children. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto; 1999.

- 19.Keating DK, Hertzman C, eds. Developmental Health and the Wealth of Nations. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999.

- 20.Toward a Healthy Future: Second Report on the Health of Canadians. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Federal, Provincial and Territorial Advisory Committee on Population Health; 1999.

- 21.Health Care in Canada 2000: A First Annual Report. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2000:72.

- 22.Capital Health. The supersize generation: responding to the obesity epidemic. Paper presented at: Strategic Planning Workshop, June2001, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

- 23.Department of Public Health, Montreal-Centre. Paper presented at: Launching the Metropolitan Monitoring Centre on Social Inequality and Health seminar, May2001, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

- 24.Morris P, Michaelopoulos C. The Self-Sufficiency Project at 36 Months: Effects on Children of a Program That Increases Parental Employment and Income. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Social Research and Demonstration Corp; 2000.

- 25.Equality, Inclusion and the Health of Canadians. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Council on Social Development; 2001.

- 26.Investing in Children and Youth: A National Children’s Agenda. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: National Children’s Alliance; 1998.

- 27.Rapport d’enquete sur les besoins des familles en matière de services de garde éducatifs. Quebec, Quebec, Canada: Institut de la Statistique Quebec; 2001:108.

- 28.Social Inclusion Through Early Childhood Education and Care. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Laidlaw Foundation; 2002.

- 29.Helping Communities Give Children the Best Possible Start. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Human Resources Development Canada; 1999.

- 30.Ministry of Children and Family Development Service Plan 2002/2003 to 2004/2005. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development; 2002.

- 31.Tracking Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2001.

- 32.Report of the Medical Officer of Health: How Healthy Are We? Edmonton, Alberta, Canada: Capital Health; 2002.

- 33.A Report on the Health of British Columbians. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: British Columbia Ministry of Health; 1999.

- 34.The Maclean’s Health Reports. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Maclean Hunter Publishing Ltd; 1999.

- 35.Fyke KJ. Caring for Medicare: Sustaining a Quality System. Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada: Commission on Medicare; 2001.

- 36.Emerging Solutions: Report and Recommendations. Quebec, Quebec, Canada: Clair Commission; 2001.

- 37.The Health of Canadians—The Federal Role. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; 2001.

- 38.Romanow R. Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002.