Abstract

Philip Morris Companies, the world’s largest and most profitable tobacco seller, has changed its corporate name to The Altria Group. The company has also embarked on a plan to improve its corporate image.

Examination of internal company documents reveals that these changes have been planned for over a decade and that the company expects to reap specific and substantial rewards from them.

Tobacco control advocates should be alert to the threat Philip Morris’s plans pose to industryfocused tobacco control campaigns.

Company documents also suggest what the vulnerabilities of those plans are and how advocates might best exploit them.

PHILIP MORRIS COMPANIES, the nation’s largest and most profitable tobacco seller, announced in late 2001 that it would be changing its name to The Altria Group.1 As the maker of Marlboro, the world’s top-selling cigarette brand, Philip Morris is a familiar name. In recent years, tobacco control campaigns have focused effectively on the industry’s role in promoting tobacco use, and this familiar name has made a recognizable target. However, under the company’s new proposal, “Philip Morris” will only refer to the tobacco operating companies under the larger “Altria Group” corporate umbrella, thus insulating both the corporation and its other operating companies—notably, Kraft General Foods—from the taint of tobacco. Holding the company as a whole responsible for its role in tobacco-related death and disease will thus become more difficult.

In preparing this article, we searched the Philip Morris Incorporated Document Web site (http://www.pmdocs.com), which provides access to millions of corporate documents, released as a result of the settlement of the state attorneys general lawsuits. Using terms such as “image,” “corporate identity,” and “Altria,” as well as names of individuals and consulting companies in a “snowball” search strategy,2 we found more than 400 relevant documents dating back to the late 1980s. We also examined news articles following Philip Morris’s announcement.

ALTRIA

Changing the corporate name is a long-term strategy for the company, having been under discussion since 1989.3 This effort has involved several consulting groups and public relations firms over the past dozen years; extensive, repeated surveys of the public and opinion leaders; and high-level corporate meetings. Philip Morris executives believed that a name change might solve a multitude of problems. The company’s consultants, the Wirthlin Group, concluded in 1992 that Philip Morris had relatively low name recognition, given its dominance in the cigarette and food markets. That recognition was almost entirely negative, associated only with tobacco.4 Publicity would exacerbate the problem. That same year, a Worldwide Corporate Affairs Network workshop on “ways to win with” various constituencies suggested that financial analysts, state and local governments, retail consumers, and the general public would all respond positively to “a more neutral corporate name.”5 The Wirthlin Group concurred: “The name change alternative offers the possibility of masking the negatives associated with the tobacco business,”6 thus enabling the company to improve its image and raise its profile without sacrificing tobacco profits.

Philip Morris executives thought a name change would insulate the larger corporation and its other operating companies from the political pressures on tobacco. Previously, “Philip Morris” referred to the tobacco operating companies (Philip Morris USA and Philip Morris International), the Philip Morris Capital Corporation (an industrial leasing company), and the larger corporation, Philip Morris Companies, which also encompassed Kraft. Thus, tobacco control advocates could easily link the relatively uncontroversial food business to the cigarette industry through the parent company name. These connections were particularly useful for organizing boycotts (see http://www.infact.org).

Under a new name, however, those links will be much less obvious. “Philip Morris” will apply only to the tobacco companies. After establishing the new name, according to a 1993 meeting transcript, the company planned to tell pressure groups, “You should talk to our operating companies about specific issues.”7 The different names will distance the corporation and its other operating companies from negative publicity. The relationship will be similar to that of Lorillard and Loews. Although the tobacco company Lorillard is wholly owned by Loews, neither Loews nor its consumer subsidiaries, Bulova, Loews Hotels, and CNA Financial Services (see http://www.loews.com/A557CC/Loews.nsf/aboutloews.htm), have been a significant target of tobacco control efforts.

There are more tangible reasons for a name change as well. Philip Morris’s Corporate Affairs Five-Year Plan for 1990 to 1994 declared that image could affect the company’s marketing success, legislative success, financial ratings, and ability to hire and retain good employees.8 A concurring 1994 proposal from CS First Boston Bank asserted that Philip Morris stock was undervalued because Philip Morris was “perceived [italics in original]” to be a tobacco company. If Philip Morris did nothing about this, the bank warned, it would continue to suffer financially: “we do not believe the tobacco ‘taint’ will be short lived.”9

The name “Altria” was chosen out of many possibilities.10 Once it was announced, one brand consultant remarked that the name’s purpose was “to make [Philip Morris] invisible.”11 Another consultant implicitly agreed. “As a consumer brand name, Altria would be dreadful because you don’t know what it means. . . . But since the only thing you will be able to buy that is called Altria will be a share of stock,” he concluded that it didn’t matter.12 The actual meaning of “Altria” has been a matter of discussion in the media. Philip Morris claimed it was derived from the Latin “altus,” meaning “high,” representing the company’s desire to “ ‘reach higher’ to achieve greater financial strength and corporate responsibility.”13 Some commentators pointed out that the “r” in Altria suggests a derivation from “altruism.”14 Philip Morris denied that this was the intention.13

Company executives recognized that a name change had some potential hazards. One was that “[s]ome might well attack the move as running from tobacco.”15 Even worse was the fear that the company “will be instantaneously labeled a tobacco company as soon as we launch the repositioning. . . . No gain. . . . Lots of pain!”7 To counter this, Philip Morris had to “create a perception of change that is deeper than just a name change,” public relations firm Burson-Marsteller warned.3 Philip Morris management concurred: “This is critical to credibility.”7 If it turned out to be only a name change, “it’s doomed.”6,7

“CONSUMER PACKAGED GOODS”

Philip Morris executives also discussed new ways of formulating the company’s identity. Shortly after the acquisition of Kraft, Guy Smith, the vice president of corporate affairs, acknowledged that “for decades the company has spent enormous sums of money instilling in the public mind what it is—a tobacco company.” Consequently, “altering that perception is a formidable task.”16 Variations of “consumer packaged goods company” were used for this purpose throughout the early 1990s.4,7,8,17,18 The Wirthlin Group found in 1993 that “simply providing a full description of the company as a ‘leading consumer products company’ ” led people to rate the company much more favorably.19 And at a corporate meeting held in late 1993 to discuss “repositioning” Philip Morris, it was suggested that the company “explore redefining investor category of packaged consumer goods. . . . In other words, create a new category and name ourselves No. 1!”7 This phrase had another advantage: “Forty percent of the general public can’t even guess what a consumer packaged goods company is; the rest offer a wide variety of definition [sic].”17 Or, as someone wrote on the Wirthlin Group’s chart demonstrating this fact, the “term has no meaning to people.”20

Such repositioning had its own risks. Emphasizing Philip Morris’s size could bring a backlash. Philip Morris wanted the sheer number (more than 200) of food and beverage brands they owned to signify “choice” to consumers.17,21–23 But their consultants pointed out that it might instead suggest “high prices/less choice because it is monopolistic.” The consultants recommended that Philip Morris “avoid the big business association with greed/profit orientation.”4

WHAT’S AT STAKE

Philip Morris’s name change to The Altria Group will be a very expensive undertaking—indeed, it doubtless already has been—and the company expects to reap great rewards. Chief among these are increased stock value, greater credibility and favor among the public and opinion leaders, and concomitantly more political, legislative, and social influence. Underpinning all of these are the company’s hopes of acquiring a layer of insulation between the larger corporation and the legal and ethical consequences of being in the tobacco business.

Unless tobacco control activists take a strong, persistent, and consistent stand to combat Philip Morris’s new image campaign, it could well succeed. According to a national opinion survey sponsored by Philip Morris, the general public believed that Philip Morris could change its image by getting out of the cigarette business, being “honest (especially about the relationship between smoking and cancer),” or stopping tobacco advertising, especially that aimed at children. But some also responded that “The easiest way out would be to change their name.”4,19

This will be a struggle over image, and the company has a powerful advantage. Philip Morris has been in the business of marketing a product that is almost entirely image for over 150 years.24 The meaning of cigarettes lies entirely in their packaging and marketing—a brand’s actual qualities have little to do with the public’s perception of it. Yet each brand has a distinct identity and meaning of its own; even nonsmokers can name “differences” between Virginia Slims, Marlboro, and Benson & Hedges.

Philip Morris will be marketing its new image, “consumer packaged goods company,” and new name, Altria, which, like cigarettes, are empty vessels waiting to be filled with meaning. Tobacco control advocates should try to establish that meaning before the company can.

So far, Philip Morris has been extremely cagey. In news stories, company spokespeople have emphasized that the new name is for “clarity” and reflects Philip Morris’s “evolution.”1 But the company’s internal documents show that Altria, rather than clarifying, is intended to obscure the fact that Philip Morris’s main source of profits is still tobacco.13 Although numerous negative or sarcastic commentaries about the name have been published, Philip Morris has not responded.12,14,25–29 Steve Parrish, senior vice president for corporate affairs, denies that Philip Morris is attempting to distance itself from tobacco. “We are not lessening our commitment to the business,” he told the New York Times. “Philip Morris means tobacco.”30

He gives the impression of candor, but the reality is subtler. “Philip Morris” will continue to refer to tobacco, while Altria avoids the connotation. Philip Morris has been working on this change for more than a dozen years. Now that it has been announced, the company is prepared for the transition to take time.

Philip Morris wants to change its image without appearing to try. Like the class misfit trying to fit in with the cool kids, Philip Morris knows that the appearance of effort is fatal, drawing attention to why it shouldn’t be accepted by the community of “good corporate citizens.” Therefore, Philip Morris would have us believe that they have already made the necessary changes. The company is presenting the name and repositioning as the culmination of a “successful effort to improve the image of the Philip Morris family of companies.”1 This effort has included “Ask First/It’s the Law” (a program that stipulated company sanctions on retailers who sold cigarettes to minors)31 and the launch of the Philip Morris Web site in 1999.32 The Web site (http://www.philipmorris.com) acknowledges that smoking is addictive and causes cancer and other diseases.

Parrish described the Web site as part of program of “constructive engagement.”32 Although he claimed to the press that this was an effort to “open a dialogue,”33 his remarks in internal documents stress that the Web site is part of an “image enhancement effort.”32 Philip Morris’s support of anti–domestic violence programs is yet another part of this effort.30 The company has spent more on publicizing their philanthropy in this and other arenas than they spent on the good works themselves, which strongly suggests that image is more important than charity.34,35 Philip Morris claims that the company is already “viewed as changing for the better and becoming a more responsible corporate citizen.”1 Some tobacco control advocates have argued that the name change represents a change in direction from these image enhancement efforts.36 However, the documents make clear that they are all part of one well-planned and coordinated campaign.

WHAT CAN ADVOCATES DO?

Philip Morris changed its name to The Altria Group on January 27, 2003 (see http://www.altria.com). One of Philip Morris’s biggest fears was that change would be futile, since the new company would remain identified with tobacco. Therefore, advocates must spotlight and sustain public awareness of the Altria–tobacco link. Altria is being positioned as “responsible” and “open and responsive to evolving societal demands” (according to http://www.altria.com/about_altria/01_01_02_MessageChairman.asp). Advocates’ demand should be clear and unmistakable: stop marketing tobacco. Truly responsible business practice demands nothing less. Advocates should ask the company to respond publicly, meaningfully and responsibly to that demand, in keeping with the company’s own statements. Until that happens, “Altria means tobacco” should be a guiding principle for any antismoking campaign aimed at Altria.

Additionally, Philip Morris’s own research indicates that they are very unpopular with the public and with leaders.19,37–40 “Altria is Philip Morris” is another message advocates should work to deliver.

Advocates should also resist being sidelined to the Philip Morris operating company. The Wirthlin Group concluded that “The environment for the company is not favorable particularly if we are positioned narrowly” and that “fighting public battles over tobacco issues” was not an effective tactic and could even make influencing policy “more difficult . . . if linked to tobacco too directly [italics in original].”23 “Altria” is an effort to broaden the issues, to include food and beverages in the discussion, thereby diluting the tobacco issue. Thus, it is important to make Altria fight those battles. Force them to explain why “Altria” is different or should not be held accountable; this will keep the tobacco connections out in the open.

Philip Morris’s use of “choice” should be undermined in precisely the ways they fear. Contrast choice with addiction, and with the involuntary inhalation of secondhand smoke. Public health advocates could develop campaigns that contrast “choice” with “monopoly” as well. Philip Morris’s consultants warned that that the company “must avoid publicity and perceptions that dramatize its size, such as how much of the grocery shelf space/sales are controlled by P/M.”4

This may be a useful image for advocates to appropriate. It’s difficult to talk about the multitude of brands that Philip Morris owns, but emphasizing Philip Morris’s monopolistic tendencies might be a way around that problem. Rather than specifying each individual brand, advocates might talk about the company’s dominance of entire categories, such as cigarettes, cookies, and cereal. (For a complete list of Philip Morris products, see http://www.altria.com/download/pdf/investors_2001_AnnRpt_ProdList_Sect8.pdf).

Advocates could also work to undermine phrases such as “consumer packaged goods company.” Philip Morris is counting on the phrase’s meaninglessness to gloss over the content of their business. Tobacco control campaigns could encourage people to ask: What goods? What’s in the package? These questions can be framed to apply both to tobacco and to business practices such as aggressive marketing in developing countries and political contributions and campaigns.

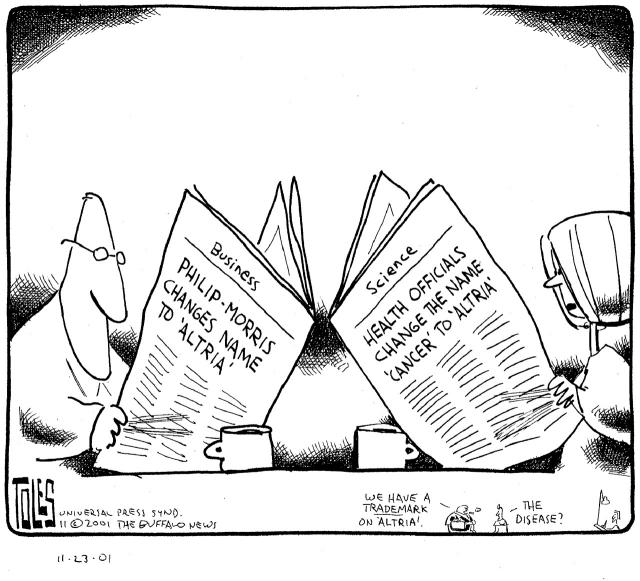

Anticipating attacks, Philip Morris has purchased Web domain names such as www.altriakills.com, www.altria-stinks.org, and www.altriasucks.net. (The authors have acquired www.altriameanstobacco.com, where a free presentation of information discussed in this commentary and helpful links are available.) Persistence is likely to be important. Humor may also be a useful tool in impressing on people the Altria–tobacco link (cartoon).

None of these strategies is new. However, they will be more important now Philip Morris has succeeded in changing its name to The Altria Group. This move is part of a campaign to boost Philip Morris’s visibility and reputation, while concealing its tobacco interests. It could be successful, particularly in combination with increasing attention to overseas markets, where tobacco control is not as well developed as in the United States. It is up to advocates to make sure that Altria does mean tobacco.

Figure .

TOLES (c)2001 The Buffalo News. Reprinted with permission of Universal Press Syndicate. All rights reserved.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Cancer Institute (grant CA090789).

We thank Larry Goldsmith and Naphtali Offen for their comments and suggestions.

Both authors contributed to conceptualization, data collection, and the writing of the manuscript.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Philip Morris Companies Inc. announces proposal to change name of parent company. 15November2001. Available at: http://www.philipmorris.com/pressroom/press_releases/pmcosincannouncment.asp. Accessed February 11, 2002.

- 2.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control. 2000;9:334–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burson-Marstellar. The corporate name. 16June1989. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023276803/6813. Accessed January 22, 2002.

- 4.Wirthlin Group. VISTA values in strategic assessment volume II. 12November1992. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2025415606/5731. Accessed February 1, 2002.

- 5.Hill & Knowlton. 920000 corporate affairs world conference workshop results draft executive summary. 1992. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023645195/5213. Accessed February 5, 2002.

- 6.Wirthlin Group. Building a strategic positioning with impact for the Philip Morris Companies. March1993. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023465153/5222. Accessed February 4, 2002.

- 7.[NewCo. outline]. 6December1993. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023437417/7455. Accessed January 16, 2002.

- 8.Philip Morris. Corporate affairs 900000–940000 five-year plan. 1990. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2070340891/0933. Accessed January 23, 2002.

- 9.CS 1st Boston. Materials prepared for discussion Philip Morris Companies, Inc. 13September1994. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2031593041/3086. Accessed January 22, 2002.

- 10.Landor Associates. Philip Morris identity development program. December1993. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023437377/7409. Accessed January 16, 2002.

- 11.Treanor J. Philip Morris buries past with Latin. Guardian.17November2001;City section:25.

- 12.Elliott S. If Philip Morris becomes Altria, its corporate image may lose some of the odor of stale smoke. New York Times.19November2001:C13.

- 13.Levin M. Philip Morris plans name change to Altria Group. Los Angeles Times.16November2001;Business section:1.

- 14.Lazarus D. Name change is an exercise in futility: so what’s in a name? Lots of spin. San Francisco Chronicle.5December2001:B1.

- 15.Fuller C. Corporate positioning and managing change. 30June1993. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023027613/7616. Accessed February 5, 2002.

- 16.Smith GL. A confidential assessment and discussion of objectives and direction for the corporate affairs department of Philip Morris Companies, Inc. 7May1989. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023276843/6860. Accessed January 23, 2002.

- 17.Hill & Knowlton. Philip Morris corporate affairs strategic plan for 930000. 3December1992. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023586677/6725. Accessed February 4, 2002.

- 18.PM image study initial findings. 1993. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2031599499/9501. Accessed January 29, 2002.

- 19.Philip Morris, Wirthlin Group. Philip Morris companies a national opinion survey—topline results. January1993. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2031599541/9584. Accessed February 4, 2002.

- 20.Wirthlin Group. Reasons why people change/do not change their ratings of Philip Morris and Kraft after discovering their relationship. July1993. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2031599304/9347. Accessed February 4, 2002.

- 21.A presentation to the committee on public affairs and social responsibility on marketing and defending the corporate brand in 930000. 12November1992. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023586662/6676. Accessed February 1, 2002.

- 22.Meeting report corporate identity program 910118. 18January1991. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2025417749/7752. Accessed January 16, 2002.

- 23.Wirthlin Group. Presentation to the committee on public affairs and social responsibility defending the corporate brand—tobacco 921216. 4December1992. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2024672254/2284. Accessed February 4, 2002.

- 24.Mahar M. The tobacco industry going up in smoke? The tobacco industry’s image grows increasingly tarnished. 9July1990. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2023028061A/8069. Accessed February 19, 2002.

- 25.Elliott S. Philip Morris identity crisis never seems to go away. New York Times.22November2001:C1.

- 26.Tobacco by any other name . . . Bangkok Post.20November2001.

- 27.Jackson DZ. Name change can’t vindicate Philip Morris: welcome to Altria Country. Boston Globe.21November2001:A23.

- 28.Skenazy L. Altria is really smokin’. New York Daily News.2December2001:39.

- 29.Kalson S. The more names change, the more things remain the same. Pittsburgh Post Gazette.28November2001;Lifestyle section:B1.

- 30.Schwartz J. Philip Morris to change name to Altria. New York Times.16November2001:C1.

- 31.Wollenberg S. Cigarette maker to battle sales to minors Philip Morris seeks to counter bad image. 28June1995. Fort Worth Star Telegram. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2044779664. Accessed January 29, 2002.

- 32.Parrish SC. Steven C. Parrish Top 70 PM-USA Landsdowne, VA 991103. 3November1999. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2070744708/4729. Accessed January 18, 2002.

- 33.Levin M. Philip Morris’ new campaign echoes medical experts tobacco: company tries to rebuild its image on TV and on line with frank health admissions about smoking and by publicizing its charitable causes. 13October1999. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2072366015A/6017. Accessed February 5, 2002.

- 34.Weiss T. Ad campaign filters image of Philip Morris. Hartford Courant.29May2001;Life section:D1.

- 35.Big tobacco’s latest smoke screen. San Francisco Chronicle.27November2000:A22.

- 36.Myers ML. Philip Morris changes its name, but not its harmful practices. Tob Control. 2002;11:169–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Continuous cigarette tracking study—900300 900400 company awareness module. April1990. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2060055417/5463. Accessed January 29, 2002.

- 38.Wirthlin Group. Philip Morris Companies a national opinion survey. December1992. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2025415379/5399. Accessed February 1, 2002.

- 39.Wirthlin Group. US image study—general public—topline results. December1992. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2031599430/9434. Accessed February 4, 2002.

- 40.Wirthlin Group. Corporate image and issues, a survey of the American public and opinion leaders. April1994. Available at: http://www.pmdocs.com. Bates no. 2031599097/9189. Accessed January 29, 2002.