Abstract

Objectives. The purpose of the present study was to compare the associations of state-referenced and federal poverty measures with states’ infant and child mortality rates.

Methods. Compressed mortality and Current Population Survey data were used to examine relationships between mortality and (1) state-referenced poverty (percentage of children below half the state median income) and (2) percentage of children below the federal poverty line.

Results. State-referenced poverty was not associated with mortality among infants or children, whereas poverty as defined by national standards was strongly related to mortality.

Conclusions. Infant and child mortality is more closely tied to families’ capacity for meeting basic needs than to relative position within a state’s economic hierarchy.

During infancy1–5 and throughout childhood,2–6 poverty has been found to be an important predictor of risk for mortality from leading causes of death at these ages, including perinatal conditions,2,5 congenital anomalies,2,3 motor vehicle injuries,2,3 and homicide,2,3,5 as well as from all causes combined.1–6 Child poverty has usually been defined in relation to the federal poverty line, either directly through comparisons of reported income with established poverty thresholds7 or indirectly by assessments of eligibility for means-tested governmental assistance programs.

The federal poverty line, an absolute measure of childhood deprivation that provides a common standard for all US children, was originally designed to represent roughly 3 times the average cost of the least expensive nutritionally adequate food plan, as determined by the Department of Agriculture.8 The federal poverty standard has been criticized for its incorporation of outdated assumptions about economies of scale in food consumption and the cost of food relative to housing, as well as its failure to take into account taxes, job-related expenses, and the value of noncash benefits9,10; however, it remains the official benchmark for defining economic deprivation among both children and adults.7

Over the past 10 years, substantial research and policy interest has focused on the concept of “relative deprivation” and its implications for health.11 This approach suggests that, between and within rich countries, “relative” rather than absolute levels of income are most important in terms of influencing public health.12,13 This focus on relative deprivation has played out amid heightened interest in income inequality among children14 as well as among the population more generally,15,16 and the relative deprivation concept has informed the idea that poverty may be more appropriately conceptualized and measured relative to local rather than national conditions.

If relative deprivation occurs via psychosocial mechanisms involving perceptions of relative disadvantage, then this idea makes sense, in that individuals are perhaps more likely to perceive local conditions as most relevant to them. Indeed, Rainwater and colleagues argued that using a locally referenced poverty standard

brings the definition of a poverty line closer to the social reality of the lives of the people being studied . . . [and] takes into account variations in the cost of living, differences in consumption bundles, and relevant differences in social understanding of what consumption possibilities mean for social participation and social activities.17

Indexing child poverty to geographically proximate economic conditions may well be effective in capturing social exclusion relative to others living in a particular area; however, it is not clear how children’s poverty status, defined in this way, might be related to their health. In this study, we examined the association between state-level child and infant mortality rates and 2 measures of child poverty, one referenced to a local state standard and another referenced to the federally defined poverty standard.

METHODS

State-specific mortality data are included in the National Center for Health Statistics’ Compressed Mortality Files (available at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Wonder Web site18); we obtained data on state-specific all-cause mortality rates among infants younger than 12 months and children aged 1 to 14 years for the years 1995 through 1997. In the case of the 1- to 14-year group, we adjusted mortality rates for age by using the 2000 US age distribution divided into 1- to 4-year and 5- to 14-year ranges.

We defined child poverty rates in 2 ways. First, we obtained estimates of the percentage of children living below the federal poverty level in each state from the 1996 small-area income and poverty estimate files prepared by the US Bureau of the Census.19 In 1996, a family consisting of a couple and 2 children was considered to be living in poverty if their income was less than $15 911.20 In our analyses, we used the poverty rates that most nearly conformed to the child ages of interest. In the case of the 1- to 14-year age group, we used the percentage of children younger than 18 years living in poverty; for the infant mortality analyses, the closest available age-specific poverty rate was that among children younger than 5 years.

Second, we used state-referenced poverty rates for children calculated by Rainwater and colleagues.17 Rainwater et al. determined the percentage of children whose family incomes were less than one half of the median equivalent income in a given state, a strategy for defining poverty often used in comparative analyses.17,21 They combined Current Population Survey data for the years 1995 to 1997, using a set of specially produced weights to accurately estimate counts of children and an equivalence scale to take household size and family head’s stage in the life course into account. Because of small population sizes, Rainwater et al. combined some states into multistate groups of 2 to 4 units.

In our analyses, we assigned the overall poverty rate of each group to its component states. We used the state-specific poverty rates calculated by Rainwater et al. for children younger than 18 years in our child mortality analyses, and we used their rates for children younger than 6 years in our infant mortality analyses.

As an alternative to using conventional federal poverty rates in their comparisons, Rainwater and colleagues also computed the percentage of children in each state whose family incomes were less than half the national median equivalent. Because the nationally referenced poverty rates they produced by this method were highly correlated with standard, federally defined rates (r = 0.91), we decided to use the more familiar federal poverty line definition described earlier.

We also obtained median 1996 incomes for each state from the Census Bureau’s small-area income and poverty estimate files. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients to assess associations between child and infant mortality and poverty defined according to national and state-referenced poverty standards. We used multivariate ordinary least squares models to assess the associations of child and infant mortality with state-referenced child poverty rates and state median incomes.

RESULTS

Table 1 ▶ ranks states in terms of percentages of children younger than 18 years who were poor, according to state-referenced and federal poverty standards, during the study period. Clearly, the 2 poverty definitions produced very different state rankings. The 3 states with the highest state-referenced child poverty rates were New York, California, and Massachusetts; these states ranked 9th, 8th, and 37th, respectively, when the absolute federal standard was used. Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Jersey were also among the top 10 most impoverished states according to the local standard; in terms of the national poverty definition, however, they were far down on the list, at 36th, 25th, and 42nd, respectively.

TABLE 1—

US States Ranked According to State-Specific Child Poverty Standard, National Poverty Standard, and Median Income, 1996

| State | State Standard, % | State | Federal Standard, % | State | Median Income, $ |

| 1. New York | 26.3 | 1. Louisiana | 29.9 | 1. West Virginia | 25 760 |

| 2. California | 25.7 | 2. Mississippi | 29.9 | 2. Mississippi | 26 901 |

| 3. Massachusetts | 24.2 | 3. New Mexico | 29.8 | 3. New Mexico | 27 014 |

| 4. Arizona | 23.6 | 4. West Virginia | 29.8 | 4. Arkansas | 27 367 |

| 5. Louisiana | 22.8 | 5. Texas | 25.8 | 5. Oklahoma | 27 648 |

| 6. Connecticut | 22.7 | 6. Arkansas | 25.7 | 6. Montana | 28 714 |

| 7. Rhode Island | 22.7 | 7. Kentucky | 25.5 | 7. Louisiana | 28 921 |

| 8. New Jersey | 21.8 | 8. California | 25.3 | 8. Alabama | 29 618 |

| 9. Illinois | 21.7 | 9. New York | 25.2 | 9. South Dakota | 29 810 |

| 10. New Mexico | 21.6 | 10. Oklahoma | 25.1 | 10. Kentucky | 30 630 |

| 11. Florida | 21.2 | 11. Alabama | 25.0 | 11. North Dakota | 30 798 |

| 12. Texas | 20.7 | 12. Arizona | 24.5 | 12. Florida | 31 008 |

| 13. Kentucky | 20.5 | 13. South Carolina | 23.1 | 13. Tennessee | 31 097 |

| 14. Alabama | 20.3 | 14. Georgia | 23.0 | 14. Wyoming | 31 173 |

| 15. Michigan | 19.5 | 15. Florida | 22.3 | 15. Arizona | 32 708 |

| 16. Washington | 19.0 | 16. Tennessee | 21.7 | 16. South Carolina | 32 728 |

| 17. Mississippi | 18.9 | 17. Montana | 21.6 | 17. Texas | 32 773 |

| 18. Delaware | 18.8 | 18. Michigan | 19.0 | 18. Missouri | 32 947 |

| 19. Georgia | 18.8 | 19. North Carolina | 18.8 | 19. Maine | 33 002 |

| 20. Maryland | 18.8 | 20. Illinois | 18.4 | 20. Idaho | 33 279 |

| 21. Virginia | 18.8 | 21. Missouri | 18.4 | 21. Vermont | 33 352 |

| 22. Ohio | 18.6 | 22. South Dakota | 18.3 | 22. Nebraska | 33 562 |

| 23. West Virginia | 18.5 | 23. Hawaii | 17.9 | 23. Kansas | 33 610 |

| 24. Pennsylvania | 18.4 | 24. Oregon | 17.6 | 24. Iowa | 33 721 |

| 25. Tennessee | 18.2 | 25. Rhode Island | 17.5 | 25. Georgia | 33 763 |

| 26. South Carolina | 18.0 | 26. Maine | 17.0 | 26. Ohio | 34 198 |

| 27. Oklahoma | 17.6 | 27. Ohio | 17.0 | 27. North Carolina | 34 487 |

| 28. North Carolina | 17.2 | 28. Washington | 16.7 | 28. Pennsylvania | 35 109 |

| 29. Oregon | 16.2 | 29. Virginia | 16.6 | 29. Oregon | 35 144 |

| 30. Alaska | 16.1 | 30. Pennsylvania | 16.5 | 30. Indiana | 35 502 |

| 31. Hawaii | 16.1 | 31. Idaho | 15.9 | 31. New York | 35 696 |

| 32. Minnesota | 15.8 | 32. Delaware | 15.3 | 32. Utah | 36 360 |

| 33. Wisconsin | 15.1 | 33. North Dakota | 15.0 | 33. Rhode Island | 36 402 |

| 34. Arkansas | 14.1 | 34. Vermont | 14.9 | 34. Washington | 37 847 |

| 35. Idaho | 13.9 | 35. Alaska | 14.8 | 35. Nevada | 38 213 |

| 36. Montana | 13.9 | 36. Connecticut | 14.8 | 36. Michigan | 38 266 |

| 37. Wyoming | 13.9 | 37. Massachusetts | 14.7 | 37. Virginia | 38 510 |

| 38. Indiana | 13.8 | 38. Maryland | 14.4 | 38. Wisconsin | 38 598 |

| 39. Missouri | 13.8 | 39. Colorado | 14.3 | 39. California | 38 691 |

| 40. Maine | 13.7 | 40. Kansas | 14.3 | 40. Colorado | 38 923 |

| 41. New Hampshire | 13.7 | 41. Wyoming | 14.3 | 41. Illinois | 39 490 |

| 42. Vermont | 13.7 | 42. New Jersey | 13.8 | 42. Delaware | 39 701 |

| 43. Colorado | 13.1 | 43. Nevada | 13.7 | 43. Minnesota | 39 791 |

| 44. Nevada | 13.1 | 44. Indiana | 13.0 | 44. New Hampshire | 40 153 |

| 45. Utah | 13.1 | 45. Nebraska | 12.7 | 45. Massachusetts | 40 686 |

| 46. Iowa | 13.0 | 46. Iowa | 12.6 | 46. Hawaii | 43 677 |

| 47. Kansas | 13.0 | 47. Wisconsin | 12.2 | 47. Maryland | 44 196 |

| 48. Nebraska | 13.0 | 48. Minnesota | 11.7 | 48. Alaska | 44 797 |

| 49. North Dakota | 12.3 | 49. Utah | 11.3 | 49. Connecticut | 44 981 |

| 50. South Dakota | 12.3 | 50. New Hampshire | 7.8 | 50. New Jersey | 46 872 |

Note. State-specific poverty rates are 1995–1997 averages.

Table 1 ▶ also lists states according to 1996 median income, from lowest to highest. As would be expected, states with lower median incomes also tended to be those with higher poverty rates according to the absolute federal standard (r = –0.64, P < .0001). For example, the 5 states with the lowest median incomes were all among the top 10 in terms of federally defined poverty. In contrast, these same states ranked between 10th and 34th in regard to state-referenced poverty level. Overall, state-referenced poverty rates were not significantly associated with median income (r = 0.14, P = .33).

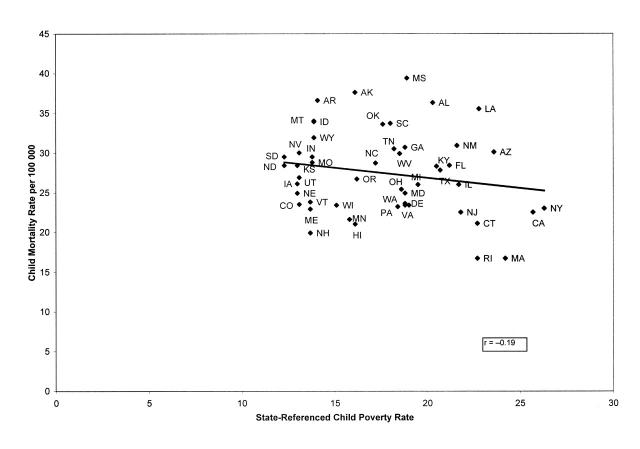

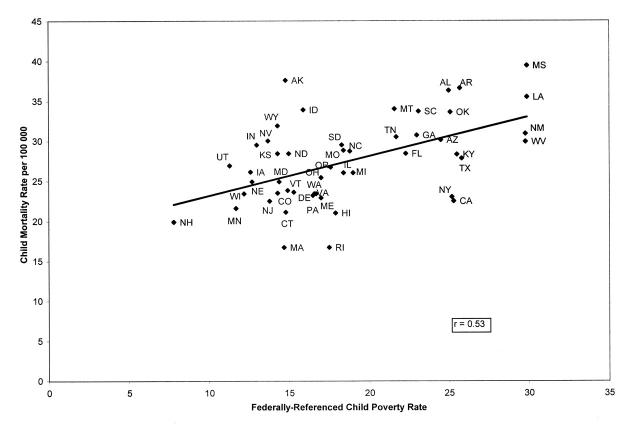

Figure 1 ▶ shows child mortality rates plotted against state-referenced child poverty levels. The association between mortality and state-referenced child poverty was negative, although the correlation of –0.19 was not statistically significant (P = .19). In contrast, Figure 2 ▶ indicates that the correlation was positive when child poverty was defined according to the absolute federal standard (r = 0.53, P < .0001); higher poverty rates were associated with increased child mortality. A similar pattern of results was seen in the case of infant mortality (data not shown). State-referenced poverty levels were not significantly associated with infant mortality rates (r = 0.21, P = .15), whereas a significant positive association (r = 0.47, P = .0005) was found between infant mortality and the federal poverty standard.

FIGURE 1—

Association between child mortality rates and state-referenced child poverty rates: US states, 1995–1997.

FIGURE 2—

Association between child mortality rates and federally referenced child poverty rates: US states, 1995–1997.

Regression analyses estimating mortality as a function of median income and statereferenced child poverty rates also indicated that absolute levels of economic resources were more strongly associated with mortality risk. Among children aged 1 to 14 years, state median income was significantly (P < .0001) and inversely related to child mortality. An increase in median income of 1 standard deviation observed across the 50 US states was associated with a reduction of 3.2 child deaths per 100 000 population, or approximately 10% of the average child mortality rate. Consistent with findings from the bivariate correlation analyses, state-referenced poverty rate was not significantly related to mortality in the multiple regression model. The analysis for infants younger than 12 months yielded comparable findings. These results indicate that once absolute level of resources is taken into account, variation in relative economic position within states does not appear to be associated with children’s mortality risk.

DISCUSSION

Whereas the concept of relative deprivation may have value for certain age groups and certain health outcomes, the present results show that if we are interested in understanding differences in child mortality across the United States, we need to use indicators of absolute rather than relative poverty. Consistent with previous research,1–3 our results indicate that state child and infant mortality rates are significantly associated with states’ levels of child poverty when that poverty is defined with respect to an absolute standard of need relevant for all US children: the federal poverty line. Our findings showed that child poverty relative to a more local, state-based standard is not associated with child mortality. Children’s survival prospects appear to be more closely tied to their families’ capacity for meeting basic needs than to the position at which their families find themselves within their state’s economic hierarchy.

In some cases, defining poverty solely by relative position with regard to state median income obscures substantial underlying deprivation. For example, according to the state-referenced poverty standard, Arkansas and Montana appear comparatively well off, ranking 34th and 36th in terms of child poverty levels. The bottom fifth of families in these 2 states, however, have average incomes of only $10 771 and $10 762, respectively.22 In contrast, Connecticut has the sixthhighest child poverty rate according to the state-referenced standard, whereas the average income among the bottom fifth of the state’s families is more than 50% higher, at $17 615.22

It has recently been suggested that lower relative position in the local economic distribution can have adverse effects on health. For example, Wilkinson12 has argued that negative perceptions of social rank, as indicated by relative income, adversely affect individual health through psychoneuroendocrine mechanisms and stress-related behaviors and exert a negative impact on societal well-being through reduced social interaction and civic participation. Studying US states, Kennedy and colleagues23,24 found that poorer self-rated health and elevated mortality risks among adults were associated with increased state-level income inequality; these authors proposed psychosocial processes, including perceptions of relative social deprivation, as an important mechanism in determining health outcomes.

The measure of relative deprivation used here focused on the proportion of children below a locally determined income cutoff point. As a result, our measure is not directly comparable with income inequality measures such as the Gini coefficient, in that our measure does not consider the total income distribution and may not have the same relationship to absolute material hardship. Thus, although our results may not be directly comparable with those of studies focusing on the effect of income inequality on health, they clearly show that “relative” child poverty, as defined by a locally referenced cutoff point, is not associated with infant and child mortality.

One possible reason for this finding is that the proportion of children whose family incomes are less than half the median income for their state has little to do with how rich that state is on average (as indicated by median income). If indeed perceptions of relative poverty are operating to influence child health, our data could be interpreted to suggest that they do so in terms of national rather than more local comparisons. An alternative interpretation, one that we favor, is that child mortality is much more closely linked to gaps in meeting basic needs and services, as indexed by the federally defined poverty standard.

Our findings also underscore the importance of monitoring levels of material resources available to disadvantaged families with children across states. The welfare reform legislation of 199625 discontinued entitlements to cash assistance and greatly expanded state latitude in the design and implementation of benefit programs for families. Subsequently, there has been increasing variation and instability among states and localities in monetary support for programs related to child welfare26 and an unparalleled decrease in the total number of children receiving public benefits.27 These changes may have important implications for infant and child health.27,28

In a political climate of devolution of programmatic and financial decisionmaking to the states, an important role remains for federally defined standards that can be applied to every infant and child residing in the United States. In view of the association demonstrated here between child deprivation levels and mortality risk, failure to identify and ameliorate conditions in which families possess inadequate resources may have serious consequences for children’s health and for their life chances.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Association of Schools of Public Health agreement S1091.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for this study.

M. M. Hillemeier, J. Lynch, and S. Harper contributed to conceptualization of the study, analysis of the data, and the writing of the article. T. Raghunathan contributed to analysis of the data and to the writing of the article. G. A. Kaplan contributed to the writing of the article.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Gortmaker SL. Poverty and infant mortality in the United States. Am Sociol Rev. 1979;44:280–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson MD Jr. Socioeconomic status and childhood mortality in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1131–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nersesian WS, Petit MR, Shaper R, Lemieux D, Naor E. Childhood death and poverty: a study of all childhood deaths in Maine, 1976 to 1980. Pediatrics. 1985;75:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh GK, Yu SM. Infant mortality in the United States: trends, differentials, and projections, 1950 through 2010. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:957–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wise PH, Kotelchuck M, Wilson ML, Mills M. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in childhood mortality in Boston. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh GK, Yu SM. US childhood mortality, 1950 through 1993: trends and socioeconomic differentials. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:505–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalaker J, Proctor BD. Poverty in the United States, 1999. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 2000. Current Population Reports, Series P60-210.

- 8.Fisher GM. The development and history of the poverty thresholds. Soc Secur Bull. 1992;55(4):3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauser RM. Measuring socioeconomic status in studies of child development. Child Dev. 1994;65:1541–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iceland J. Poverty Among Working Families: Findings From Experimental Poverty Measures. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 2000. Current Population Reports, Series P23-203.

- 11.Lynch JW, Davey Smith G, Kaplan GA, House JS. Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ. 2000;320:1200–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson RG. Unhealthy Societies—The Afflictions of Inequality. London, England: Routledge; 1996.

- 13.Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch et al. BMJ. 2001;322:1233–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Acs G, Gallagher M. Income Inequality Among America’s Children. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2000.

- 15.Danziger S, Gottschalk P. America Unequal. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1995.

- 16.Ryscavage P. Income Inequality in America: An Analysis of Trends. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe; 1999.

- 17.Rainwater L, Smeeding TM, Coder J. Poverty across states, nations, and continents. In: Vleminckx K, Smeeding TM, eds. Child Well-Being, Child Poverty and Child Policy in Modern Nations: What Do We Know? Bristol, England: Policy Press; 2001:33–74.

- 18.CDC WONDER [search program]. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/#aboutWonder. Accessed November 14, 2002.

- 19.US Bureau of the Census. Small area income and poverty estimates, state and county estimates. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/saipe/estimatetoc.html. Accessed October 9, 2002.

- 20.US Bureau of the Census. Poverty thresholds: 1996. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/poverty/threshld/thresh96.html. Accessed October 9, 2002.

- 21.Atkinson AB, Gardiner K, Lechene V, Sutherland H. Comparing poverty rates across countries: a case study of France and the United Kingdom. In: Jenkins SP, Kapteyn A, van Praag BMS, eds. The Distribution of Welfare and Household Production: International Perspectives. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1998:50–74.

- 22.Bernstein J, McNichol EC, Mishel L, Zahradnik R. Pulling Apart: A State-by-State Analysis of Income Trends. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; 2000.

- 23.Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Glass R, Prothrow-Stith D. Income distribution, socioeconomic status, and self rated health in the United States: multilevel analysis. BMJ. 1998;317:917–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lochner K, Pamuk E, Makuc D, Kennedy BP, Kawachi I. State-level income inequality and individual mortality risk: a prospective, multilevel study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:385–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, Pub L No. 104-193 (1996).

- 26.Bess R, Leos-Urbel J, Geen R. The Cost of Protecting Vulnerable Children II: What Has Changed Since 1996? Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2001.

- 27.Smith LA, Wise PH, Chavkin W, Romero D, Zuckerman B. Implications of welfare reform for child health: emerging challenges for clinical practice and policy. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1117–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudman J, Starfield B. Children and welfare reform: what are the effects of this landmark policy change? In: Wallace HM, Green G, Jaros KJ, Paine LL, Story M, eds. Health and Welfare for Families in the 21st Century. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 1999:115–133.