Abstract

We describe an innovative approach for evaluating a men’s health center.

Using observation and interview, we assessed patient flow, referral patterns, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of the services’ usefulness. Student assistants designed evaluation tools, hired and trained research assistants, supervised data collection, interacted with city and center officials, analyzed data, and drafted a report.

To ensure patient confidentiality and anonymity, we designed an innovative observation system. The men had unique perceptions of family, requiring culturally sensitive approaches to engage them in the study. Of patients reporting to the center, 20.3% received referral services. Average satisfaction level was 5.2 (scale = 1–10).

Perceived benefits to the family for 23% of respondents included cost savings, improved access, and higher service quality.

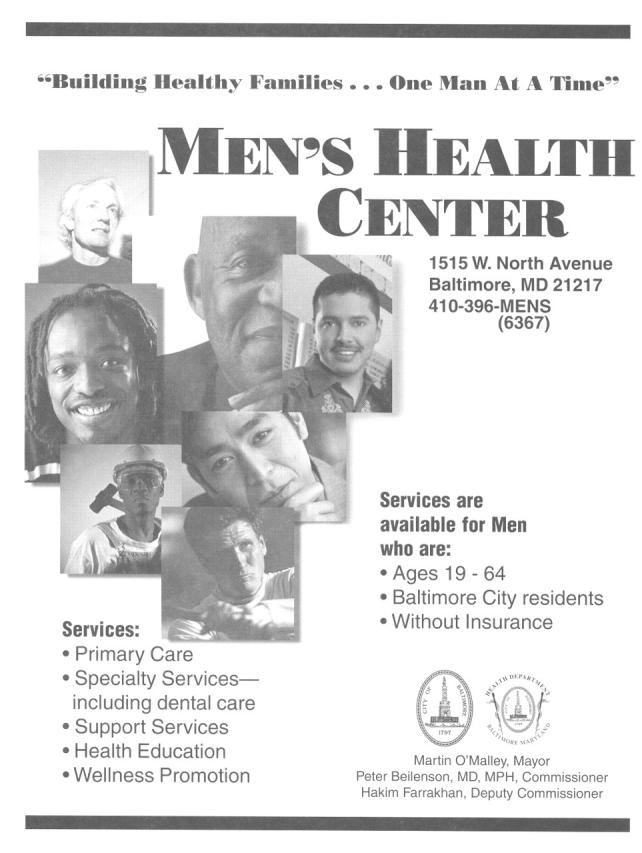

IN JANUARY 2000, THE Baltimore City Health Department conducted a survey of inner-city men, aged 18 to 64 years; it indicated that the 5 most-needed services were dental care, physical examinations, HIV testing, pharmacy services, and eye examinations. The survey also showed that 50.6% of respondents had no health insurance plans and 50% were unemployed. The Men’s Health Center was opened on April 3, 2000, under the oversight of a committee established by the Baltimore City Health Department and directed by its deputy commissioner of health (Figure 1 ▶). The center provides health screening, physical examinations, dental screening, referral services, health education, addictions counseling, HIV screening, prescription assistance, and social services, including services that provide employment assistance. Other services include smoking cessation programs, voter registration, and substance abuse counseling, and patient screening for such diseases as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and gout. Focus groups meet twice a week for counseling on domestic violence, unemployment, substance abuse, and debt leveraging for child support assistance.

FIGURE 1.

—English version of promotional flier of the Men’s Health Center (a Spanish version exists as well).

The center, which is linked to local institutions and service providers in substance abuse and laboratory services, receives funding assistance from the state and local governments as well as private philanthropic organizations for specific components of its services. For example, the Transitional Emergency Medical Housing Assistance (TEMHA) program was funded with assistance from the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, while substance abuse services are provided in collaboration with a local hospital, which uses the center as an outreach site. The center collaborates with the local Fathers Workforce and Family Development Center to provide components of family services designed to help the men reintegrate into their families.

The center provides services to men who would otherwise not qualify for funded services because they are either too old or too young. The men are either underemployed or unemployed; more serious still, some of them are unemployable men who have been passing through the penal system since they were young. As a result, many have truncated or poorly developed social, economic, and other functional skills, making them poorly prepared to join the workforce.

To evaluate program efficacy and quality with regard to patients, the Baltimore City Health Department commissioned the Morgan State University Public Health Program to do a time-and-motion study and a survey. We assessed patterns of patients’ arrival into the center, total time spent, time spent waiting, and time spent with service providers. Our survey assessed satisfaction level, referral types, and patients’ perceptions of how health information and services obtained from the center would be useful to their families.

We surveyed 338 men who entered the center and qualified for services. Management required that the center’s environment remain free of a research atmosphere and that the survey respect patients’ sensitivities and ensure confidentiality. The researchers therefore placed assistants at strategic sites throughout the center to track patients’ movement and progress through descriptions of their clothing. To determine flow patterns into the center, we recorded patient entry and exit times from each service point. Total times spent in the center waiting area and in each consultation room were recorded, stored in Microsoft Access 1997, and analyzed with Microsoft Excel 1997 (Microsoft Corp. Redmond, Wash). We collected survey data through face-to-face exit interviews. To measure satisfaction, we used a Likert scale of 1 to 10 (10 indicating highest level of satisfaction).

Using a combination of closed and open-ended questions, we recorded data on referral, usefulness, and impact of health education information and other services on family relationships. We performed descriptive statistical analyses of times recorded and domain analyses of survey interview responses related to family. Students obtained institutional review board approval, attended planning and briefing meetings with city health officials, and conducted familiarization sessions with center staff.

DISCUSSION AND EVALUATION

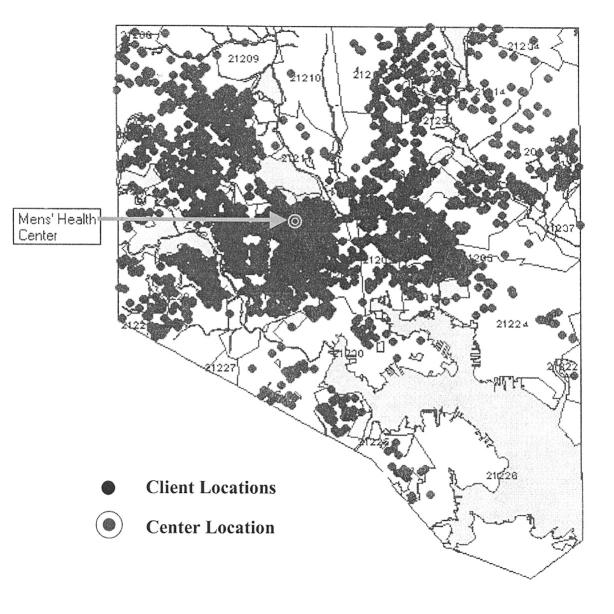

Patients from all parts of the city attended the center (Figure 2 ▶). The mean patient waiting time was 1 hour and 26 minutes (Table 1 ▶), similar to what researchers have found at other outpatient centers.1–6 The 3 most frequently made referrals were medical (24.6%), dental (20.3%), and ophthalmologic (11.6%). Approximately 22.7% of the respondents were most impressed by the knowledge that they could obtain access to care and receive quality services despite their insurance status. Over one third (37.9%) of the respondents shared center information with their families.

FIGURE 2.

—Distribution of clients of the Men’s Health Center in Baltimore City, Maryland.

Source. Map courtesy of Baltimore City Health Department.

TABLE 1.

—Time Respondents Spent in Men’s Health Center and Respondents’ Satisfaction Level

| Variable Measured | Finding |

| Time most patients entered center | 11:00–15:00 (75% of patients) |

| Mean total time spent in center | 2 h |

| Mean total time spent in waiting area | 1 h 26 min |

| Mean total time in service | 29 min |

| Overall service satisfaction level | 5.2 (Likert Scale 1–10) |

The Men’s Health Center is distinctive in several ways. It provides health care to a population with its own unique political, economic, demographic, cultural, and health needs. An innovative care environment is also provided for unemployed, underemployed, uninsured, and underinsured men. It provides a wide variety of services, including health education, addiction counseling, and referral services, to inner-city men aged 18 to 64 years.

This study indicates that men’s cultural sensitivity and competence needs are unique, and more study is required to align policy and programs to these needs. Although not yet thoroughly analyzed, our findings indicate that the way men define “family”4,7 may provide an opportunity to address wider societal issues related to family function (i.e., the social, structural, and functional dynamics of family) and the policies that impact these areas. The center project provided firsthand experience in public health leadership roles for students, especially in the area of program and project evaluation. The dynamics of survey implementation may require a balance between doctrinaire scientific research, time restraints, and the identified needs of the community. The goal will be to ensure scientific validity while maintaining cultural relevance.

KEY FINDINGS.

Patient services and patient satisfaction levels at the Men’s Health Center are comparable to those found elsewhere, and the most frequent referrals were medical, dental, and ophthalmologic.

Additional information is needed to determine the Baltimore inner-city African American male’s perception and definition of family.

The Men’s Health Center evaluation project offers unique opportunities for training in public health practice, while short-term, low-cost evaluations of this kind offer effective monitoring alternatives for program development and implementation in public health practice.

NEXT STEPS

To adequately assess whether information provided by the center assisted the men with their families, it is important to determine each patients’ unique functional and operational definition of family.8 Since the study was conducted during the center’s formative period, follow-up evaluation is needed to determine whether (1) the center continued to attract patients at the same rate, (2) utilization levels of center services and demographic and usage patterns have changed, (3) there were any changes in benefits to the family, and (4) real-time evaluation for program planning and implementation was useful for the program. It would also be useful to assess the program’s effectiveness, care quality, and validity through more focused evaluation of components of the program on a continuous basis.

The challenge will be to develop flexible, valid, reliable, low-cost evaluation tools9 for rapidly evolving programs in implementation. If proven effective, they will provide near real-time diagnoses and guidance for policy planners, administrators, and managers in community health, especially in minority populations. Finally, because of the low precision of the survey tools, we could not perform more rigorous analyses and modeling of the data we collected. Designing more precise quantitative and qualitative tools for evaluating programs of this type would provide more sensitive and specific guidance to planners, administrators, and managers.

Overall, the Men’s Health Center is a needed and useful program for addressing the unique health care needs of an otherwise disenfranchised and vulnerable population. Ongoing program and client population evaluation will assist such a program to improve its services and make them more responsive to the needs of the population it serves.

Acknowledgments

O. T. Ekundayo, project director and lead investigator, directed project activities and cowrote the report. Y. Bronner, project principal investigator, supervised the project, provided faculty instructional guidance and trained students in public health practice, and cowrote the report. W. L. Johnson-Taylor edited the report and provided guidance in writing the report and reporting quality assurance. N. Dambita, project overseer for the Baltimore City Health Department, provided statistical overview and quality assurance, edited the report for quality assurance, and made other significant contributions. S. Squire, project field coordinator, supervised field operations, performed extensive literature review, and made substantial contributions to the final report.

Human Participant Protection Institutional review board approval for this project was obtained from both the Baltimore City Health Department and Morgan State University.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Huang X. Patient attitudes towards waiting in an outpatient center. Health Serv Manage Res. 1994;7:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bamgboye E, Jarallah J. Long-waiting outpatients: target audience for health education. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;23:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rondeau K. Managing the center wait: an important quality of care challenge. J Nurs Care Qual. 1998;13(2): 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bronner Y, Dambita N, Ekundayo O, Squire S. Men’s Health Center Study. Final Report. Baltimore, Md: Baltimore City Health Department; July 2000: 1–19.

- 5.Linder-Pelz S, Streuning E. The multi-dimensionality of patient satisfaction with a center visit. J Community Health. 1985;10:42–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mckinnon K, Crofts P, Edwards R, Campion P, Edwards R. The outpatient experience. results of a patient feedback survey. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 1998;11:156– 160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman M, Ramirez-Walles J, Maton K. Resilience among urban African-American male adolescents: a study of protective effects of sociopolitical control on their mental health. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27:733–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitehead T, Peterson J, Kaljee J. The “hustle”: socioeconomic deprivation, urban drug trafficking, and low-income African-American male gender identity. Pediatrics. 1994;93(6 Pt 2):1050–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witte K, Donohue WA. Preventing vehicle crashes with trains at grade crossings: the risk seeker challenge. Accid Anal Prev. 2000;32:127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]