Abstract

Objectives. This study examined knowledge about prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening among African Americans and Whites. Because PSA screening for prostate cancer is controversial, professional organizations recommend informed consent for screening.

Methods. Men (n = 304) attending outpatient clinics were surveyed for their knowledge about and experience with screening.

Results. Most men did not know the key facts about screening with PSA. African Americans appeared less knowledgeable than Whites, but these differences were mediated by differences in educational level and experience with prostate cancer screening.

Conclusions. Public health efforts to improve informed consent for prostate cancer screening should focus on highlighting the key facts and developing different approaches for men at different levels of formal education and prior experience with screening.

Screening for prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is controversial because it is not clear whether it reduces mortality and whether the potential benefits of screening and early detection outweigh the risks.1–5 These risks include unnecessary worry and the side effects of common treatments for prostate cancer (e.g., impotence and urinary leakage from surgery or radiation therapy) particulary if early, localized prostate cancer is found.1–5 Until randomized controlled trials determine whether regular screening with PSA reduces mortality,5–9 professional organizations have issued different guidelines10–15 for prostate cancer screening. Many, including the US Preventive Services Task Force,11 recommend informing men about the known risks and potential benefits of screening.10–15

Despite professional recommendations10–15 to promote informed consent or “informed decisionmaking”16–18 for screening, knowledge about prostate cancer and screening is low.19–26 Because PSA testing has become widespread,27–30 highlighted in the mass media,31–33 and encouraged by mass screenings and advertised through a movement to create postage stamps,35–37 promoting informed consent has become an ethical issue in public health.

Although African American men have a higher incidence of prostate cancer, are more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage, and have higher mortality rates compared with Whites,38–41 they are generally less knowledgeable about the disease.24,42,43 The gap between what men know and what they ought to know in order to make an informed decision about screening has the potential to widen, particularly for African American men.

In previous studies assessing knowledge, investigators determined whether men knew facts about prostate cancer, screening, and treatment.19–25,42–43 These studies were based on facts drawn from patient education material,20,22,45 from what the investigators considered important,21,23,24,42,43,47 or from a literature review.25,42

We hypothesized that most men do not know the facts needed to provide informed consent for prostate cancer screening with PSA. In contrast to previous studies,19–25,42–47 we assessed knowledge relative to the reasonable-person standard of informed consent, using a survey based on results from a prior study by 1 of the authors.48 That study identified facts that experts in prostate cancer and African American and White couples believed men ought to know to make an informed decision about screening. Those facts formed the proposed content of informed consent by the reasonable-person standard, a legal standard defined by what a hypothetical person would need to know in order to make an informed decision.49–51

We hypothesized that there would be differences in knowledge about prostate cancer, screening, and treatment by race/ethnicity. In contrast to previous studies,23,42,43 we examined racial/ethnic differences in knowledge while controlling for educational level. Because a man’s experience with PSA screening might modify the association between race/ethnicity and knowledge, we also examined potential effect modifiers related to experience. As a result, we were more fully able to characterize differences in knowledge by race/ethnicity.

METHODS

Study Setting and Study Population

We recruited men attending the general internal medicine outpatient practices at Kelsey-Seybold Clinic (KSC) in Houston and The University of Texas–Houston (UT–H). KSC is a multispecialty practice; UT–H is a multispecialty university practice. Men attending KSC were scheduled for a periodic health maintenance examination. Men attending UT–H were scheduled for a nonurgent care visit. At UT–H, visits are not specified as periodic health maintenance examinations. At KSC in 2001, 43% of the patients were enrolled in health maintenance organizations, 29% in fee-for-service plans, 22% in preferred provider plans, 5% in Medicare, and 0.5% in Medicaid. At UT–H in 2001, 37% of the patients were enrolled in health maintenance organizations, 33% in preferred provider plans, 17% in Medicaid, 11% in Medicare, and 2% in fee-for-service plans.

We attempted to recruit 150 men from each clinic. Over 9 months in 2001, we approached 503 men aged 50 years or older on-site at KSC and UT–H who had just visited their physicians. These men were potential candidates for screening and, as clinic attendees, would have a greater opportunity to be screened than the general population. To be eligible, men had to have no prior history of prostate cancer and at least a sixth-grade education. Of the 503 men approached, 124 refused to participate, leaving 379 for whom we determined eligibility. At KSC, 9 were ineligible, and at UT–H, 66 were ineligible. This left us with 152 men at KSC and 152 men at UT–H, each of whom was paid $10 for completing a self-administered survey instrument on-site. Because nearly 90% of the respondents were either White or African American, we excluded 24 Hispanics and 9 men of other ethnicities from the analysis. This gave us 185 Whites and 86 African Americans, for a total of 271 study participants.

Survey Instrument

In 1995 a national panel of 12 experts in prostate cancer, 6 focus groups of African American and White couples, and a multidisciplinary group of physicians, patients, and ethicists arrived at facts that they believed men ought to know in order to make an informed decision about PSA testing.48 In March 2000 we surveyed the original panelists; most agreed that the facts were still accurate and relevant to informed decisionmaking.

We developed a survey to assess knowledge about prostate cancer, screening, and treatment on the basis of those facts. The survey had 3 subsections of knowledge: 9 questions about prostate cancer, 13 about screening, and 14 about treatment, for a total of 36 questions. We posed questions about knowledge as factual statements to which respondents could respond “agree,” “disagree,” or “don’t know.” The survey also included demographic questions and questions about experience with prostate cancer screening to which respondents could respond “yes,” “no,” or “don’t know.”

We pilot-tested the survey on 40 eligible men at our clinics and made revisions. On average, patients completed the survey within 15 minutes.

Study Variables

The main dependent variable was global knowledge about prostate cancer, screening, and treatment. Other dependent variables were each of the 3 subsections of knowledge: prostate cancer, screening, and treatment. We computed a mean global knowledge score for African Americans and Whites according to a total of 36 possible correct responses. Scores could range from 0 to 36. We computed a mean score for each subsection of knowledge on the basis of the total number of possible correct responses to questions about prostate cancer (9 questions), screening (13 questions), and treatment (14 questions)

The main independent variable was race/ethnicity (African American, White). Other independent variables included age (continuous variable), educational level (less than a college education, college education or higher), household income (less than $50 000, $50 000 or greater), marital status (married, not married), family history of prostate cancer (positive, negative) and clinic site (KSC, UT–H). We measured experience variables with the questions shown in Table 1 ▶.

TABLE 1.

—Experience With Prostate Cancer Screening by Race/Ethnicity: University of Texas–Houston Clinic and Kelsey-Seybold Clinic, Houston, Tex, 2001

| White, No. Responses (% Yes) | African American, No. Responses (% Yes) | |

| Did your doctor discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test with you? | 157 (38) | 54 (46) |

| Did you have the PSA test today or do you plan on having the PSA test later today or within the next week? | 155 (55) | 54 (56) |

| Have you ever heard of a PSA test? | 182 (87) | 85 (65)* |

| Have you ever been told by a doctor that you should have a PSA blood test? | 158 (88) | 55 (71)* |

| Have you ever had a PSA test? | 158 (85) | 55 (73)* |

| Note. χ2 tests were used to compare experiences between groups. No. is the number of respondents to each question. | ||

| *P ≤ .05 (χ2 test). | ||

Data Analysis

We combined data from KSC and UT–H for our analysis by race/ethnicity because there were no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics between study participants at these sites with χ2 and analysis of variance. For 33 questions for which the correct response was “agree,” we combined responses of “don’t know” and “disagree” into a single category. For 5 questions for which the correct response was “disagree,” we combined responses of “don’t know” with “agree.” In effect, “don’t know” was scored as an incorrect response.

We compared the mean global and mean subsection knowledge scores for each demographic and experience variable with the Student t test. To explore racial/ethnic differences in global knowledge scores in more detail, we compared the distribution of responses among African Americans and Whites for each knowledge question with χ2 tests.

In bivariate analyses with linear regression, we compared scores on the global and subsection knowledge scales by demographic characteristics, including race/ethnicity and experience with prostate cancer screening. We also examined interaction terms for race/ethnicity relative to global knowledge scores for each of the following potential effect modifiers related to experience with PSA: had heard of the PSA test, had been told to have a PSA test, had ever had a PSA test, had been told of the potential risks and benefits of PSA testing, and had had a PSA test at a clinic today or in the past week.

After bivariate analyses, we entered those variables and interaction terms that were statistically significant at P ≤ .25 into a stepwise linear regression model.52 We repeated this analysis for each subscore (i.e., cancer, screening, and treatment). All statistical analyses were performed with Stata 6.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Tex). Associations were considered statistically significant at P < .05.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

The mean age of respondents was similar for Whites and African Americans (Table 2 ▶). Whites had higher educational levels and household incomes and were more likely to be married than were African Americans.

TABLE 2.

—Characteristics of Study Participants by Race/Ethnicity: University of Texas–Houston Clinic and Kelsey-Seybold Clinic, Houston, Tex, 2001

| Characteristic | White (n = 185) | African American (n = 86) |

| Age, y (mean ± SD) | 61.8 ± 8.0 | 60.7 ± 9.4 |

| Educational level, %* | ||

| Less than high school | 4 | 17 |

| High school/GED | 8 | 21 |

| Some college | 22 | 27 |

| College degree | 66 | 34 |

| Household income, %* | ||

| < $15 000 | 4 | 9 |

| $15 000–$24 999 | 4 | 13 |

| $25 000–$34 999 | 6 | 14 |

| $35 000–$49 999 | 14 | 22 |

| ≥ $50 000 | 71 | 36 |

| Marital status, %* | ||

| Married | 84 | 72 |

| Not currently married | 16 | 28 |

| Family history, % | ||

| Brother or father with prostate cancer | 11 | 16 |

| Clinic site, % | ||

| Kelsey-Seybold Clinic | 46 | 52 |

| UT–H Clinic | 54 | 48 |

Note. χ2 and analysis of variance were used to test for differences in demographic characteristics between racial/ethnic groups. GED = general equivalency diploma; UT–H = University of Texas–Houston.

*P ≤ .05.

Knowledge Scores for Prostate Cancer, Screening, and Treatment by Race/Ethnicity

For less than 10% of the 36 questions assessing global knowledge, 13% of the responses were “don’t know”; for 10% to 20% of the questions, 27% of the responses were “don’t know”; and for more than 20% of the questions, 60% of the responses were “don’t know.”

African Americans had a mean global knowledge score of 17 out of 36 total points; Whites scored 21 (P < .001). For each knowledge component (i.e., prostate cancer, screening, and treatment), mean scores for African Americans were lower than mean scores for Whites. For questions about cancer, African Americans scored 5 out of 9 total points; Whites scored 6 (P < .01). For questions about screening, African Americans scored 6 out of 13 total points; Whites scored 7 (P < .001). For questions about treatment, African Americans scored 6 out of 14 total points; Whites scored 8 (P < .001). Mean global and mean subsection knowledge scores for the demographic variables are shown in Table 3 ▶.

TABLE 3.

—Mean Global and Subsection Knowledge Scores for Demographic and Experience Variables: University of Texas–Houston Clinic and Kelsey-Seybold Clinic, Houston, Tex, 2001

| Global Knowledge | Cancer Knowledge | Screening Knowledge | Treatment Knowledge | |

| Score 0–36 | Score 0–9 | Score 0–13 | Score 0–14 | |

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 17.4 ± 5.7 | 5.4 ± 2.1 | 5.8 ± 2.5 | 6.2 ± 2.5 |

| White | 20.6 ± 5.8*** | 6.1 ± 2.8** | 6.9 ± 2.4*** | 7.6 ± 2.8*** |

| Median age, y | ||||

| < 60 | 18.9 ± 6.6 | 5.7 ± 2.2 | 6.1 ± 2.6 | 7.1 ± 2.8 |

| ≥ 60 | 19.2 ± 5.6 | 5.7 ± 1.8 | 6.6 ± 2.5 | 6.9 ± 2.8 |

| Education | ||||

| ≥ College | 21.0 ± 5.9 | 6.2 ± 1.8 | 6.9 ± 2.4 | 7.8 ± 2.7 |

| ≤ High school | 16.7 ± 5.6*** | 5.1 ± 2.0*** | 5.6 ± 2.5*** | 6.1 ± 2.6*** |

| Household income, $ | ||||

| ≥ 50,000 | 20.5 ± 5.8 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 6.7 ± 2.4 | 7.6 ± 2.7 |

| < 50,000 | 16.9 ± 5.9*** | 5.1 ± 2.1*** | 5.8 ± 2.6** | 6.1 ± 2.6*** |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 19.4 ± 5.8 | 5.8 ± 1.9 | 6.5 ± 2.4 | 7.1 ± 2.7 |

| Not currently married | 17.6 ± 7.2 | 5.4 ± 2.3 | 5.7 ± 2.9 | 6.5 ± 3.0 |

| Family history | ||||

| Brother or father with PC | 20.7 ± 5.2 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 6.9 ± 2.5 | 7.8 ± 2.7 |

| No brother or father with PC | 18.9 ± 6.2 | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 6.3 ± 2.6 | 6.9 ± 2.8 |

| Clinic site | ||||

| Kelsey-Seybold Clinic | 18.9 ± 5.5 | 5.7 ± 1.9 | 6.3 ± 2.4 | 6.9 ± 2.5 |

| UT–H Clinic | 19.2 ± 6.7 | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 6.4 ± 2.7 | 7.1 ± 3.1 |

| Experience variables | ||||

| Ever heard of PSA test | ||||

| Yes | 20.3 ± 5.5 | 6.0 ± 1.8 | 6.9 ± 2.2 | 7.3 ± 2.8 |

| No or unknown | 14.5 ± 5.9*** | 4.6 ± 2.2*** | 4.1 ± 2.5*** | 5.7 ± 2.5*** |

| Ever been told to have PSA test | ||||

| Yes | 20.3 ± 5.5 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 6.9 ± 2.3 | 7.4 ± 2.7 |

| No or unknown | 15.8 ± 6.3*** | 5.1 ± 2.1*** | 4.9 ± 2.6*** | 5.9 ± 2.7*** |

| Ever had a PSA test | ||||

| Yes | 20.7 ± 5.4 | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 7.0 ± 2.2 | 7.6 ± 2.7 |

| No or unknown | 15.5 ± 5.9*** | 4.9 ± 2.1*** | 4.9 ± 2.6*** | 5.8 ± 2.6*** |

| Been told of pros, cons of PSA | ||||

| Yes | 19.6 ± 5.5 | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 6.4 ± 2.2 | 7.3 ± 2.9 |

| No or unknown | 18.7 ± 6.5 | 5.6 ± 2.1 | 6.3 ± 2.7 | 6.8 ± 2.7 |

| PSA test today or past week | ||||

| Yes | 19.9 ± 5.6 | 5.8 ± 1.8 | 6.8 ± 2.3 | 7.3 ± 2.6 |

| No or unknown | 18.3 ± 6.6* | 5.7 ± 2.2 | 5.9 ± 2.7** | 7.2 ± 3.0 |

Note. PSA = prostate-specific antigen; PC = prostate cancer; UT–H = University of Texas–Houston.

*P < .05 by Student t test; **P < .01; *** P < .001.

Knowledge About Specific Facts by Race/Ethnicity

Mean global knowledge scores for African American and White men showed that both groups knew approximately 50% of the facts. However, neither group knew the following facts, which have made PSA screening controversial and informed decisionmaking important to professional organizations: Ninety percent of African American and 97% of White men believed that regular prostate cancer screening lowers mortality from prostate cancer, even though this association is unproven. Seventy-six percent of African American and 81% of White men believed that doctors are sure that the PSA test is a useful test for prostate cancer, even though professional organizations remain uncertain about the test. An appendix showing the distribution of responses by race/ethnicity is available from the first author.

Neither group knew other facts about prostate cancer screening and treatment. Only 36% of African American and 42% of White men knew that screening for prostate cancer is most appropriate for men with at least a 10-year life expectancy. Less than 50% of African American and White men understood that false-positive and false-negative PSA test results can occur. Eighty-eight percent of African American and 91% of White men believed that treating early-stage prostate cancer would prolong life, even though it is unclear whether treatment for early, localized prostate cancer is better than watchful waiting.8

For other facts, African American and White men differed in knowledge. Compared with 60% of African American men, only 37% of White men knew that the risk of getting prostate cancer is higher in African Americans. Whereas 22% of African Americans agreed that the digital rectal examination is a blood test for prostate cancer, only 9% of Whites agreed with this incorrect response. African Americans were generally less knowledgeable than Whites about treatment options for early prostate cancer.

Experience With Prostate Cancer Screening by Race/Ethnicity

Even though less than 50% of African Americans and Whites reported that their physician had discussed with them the advantages and disadvantages of the PSA test, more than 50% of both groups reported having heard of the PSA test, being told by a physician that they should have a PSA test, or having had a PSA test. Whites were more likely than African Americans to report these 3 conditions (Table 1 ▶). Mean global and mean subsection knowledge scores for the experience variables appear in Table 3 ▶.

Stepwise Linear Regression Model for Global Knowledge Scores

In stepwise linear regression analyses, the following variables and interaction terms were significantly associated with global knowledge scores after control for covariates: educational level, having heard about the PSA test, the interaction of race/ethnicity with having heard about the PSA test, and the interaction of race/ethnicity with having had a PSA test. After controlling for the effects of other covariates, we did not find a significant association between race/ethnicity and knowledge.

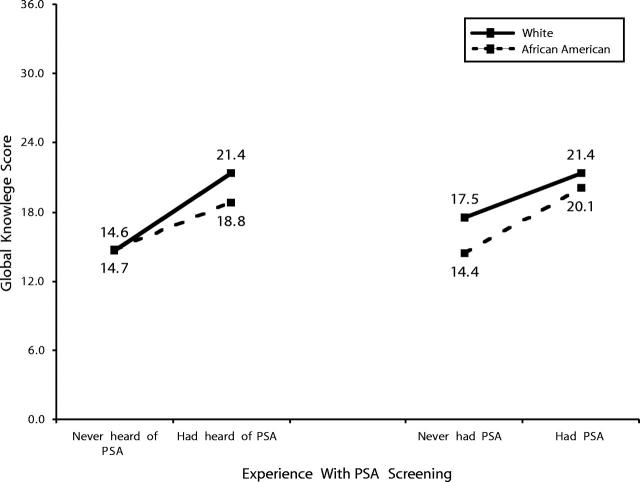

The relationship between each of the 2 effect modifiers and race/ethnicity on global knowledge scores is depicted in Figure 1 ▶. Men of both racial/ethnic groups who had heard of the PSA test were more knowledgeable than men who had not. However, among men who had heard about the PSA test, African Americans had a significantly lower mean global knowledge score (18.8 ± 5.0) compared with Whites (21.4 ± 5.3) (Student t test, P < .01). There were no significant racial/ethnic differences in knowledge among men who had never heard of PSA testing.

FIGURE 1.

—Interaction between race/ethnicity and experience with prostate specific antigen acreening on global knowledge about prostate cancer screening: University of Texas–Houston Clinic and Kelsey-Seybold Clinic, Houston, Tex, 2001

Men of both racial/ethnic groups who had had a PSA test were more knowledgeable than men who had not (Figure 1 ▶). In multivariate analyses, ever having had a PSA test had no statistically significant main effect on global knowledge. Furthermore, no significant racial/ethnic difference in mean global knowledge scores was found among men who had had a PSA test (Student t tests, P < .05). Among men who had never had PSA screening, African Americans had a significantly lower mean global knowledge score (14.4 ± 5.0) compared with Whites (17.5 ± 6.1) (Student t test, P < .05) (Figure 1 ▶).

Stepwise Linear Regression Models for Subsection Knowledge Scores

In stepwise linear regression analysis, educational level and having heard about the PSA test were significantly associated with knowledge about prostate cancer after we controlled for covariates. Educational level and having had a PSA test were significantly associated with knowledge about prostate cancer treatment. In contrast, educational level was not significantly associated with knowledge about prostate cancer screening. The following variables were significantly associated with knowledge about prostate cancer screening: having heard of the PSA test; having had a PSA test; the interaction of race/ethnicity and having heard of the PSA test; and the interaction of race/ethnicity and having had a PSA test.

Men of both racial/ethnic groups who had heard about the PSA test had a higher mean screening knowledge score than men who had never heard about the test. Among men who had heard about the PSA test, African Americans had a lower mean screening knowledge score (6.42 ± 2.21) compared with Whites (7.30 ± 2.08) (Student t test, P < .05). There were no statistically significant racial/ethnic differences in screening knowledge among men who had never heard of PSA testing.

Men of both racial/ethnic groups who had ever had a PSA test had higher screening knowledge scores than men who had not. There were no significant racial/ethnic differences in screening knowledge among men who had had a PSA test. In contrast, among men who had never had PSA screening, African Americans had a lower mean screening knowledge score (4.46 ± 2.37) compared with Whites (5.40 ± 2.73) (Student t test, P < .05).

DISCUSSION

Our findings have implications for public health promotion of informed consent for prostate cancer screening with PSA. A previous study48 identified facts that experts and couples believed men ought to know to make an informed decision about screening. The most important facts were that (1) it is unclear whether regular screening with PSA reduces mortality from prostate cancer, (2) false-positive PSA test results can occur, and (3) false-negative PSA test results can occur. We found that although African American and White men knew approximately 50% of the facts that form the proposed content of informed consent for screening with PSA48 by the reasonable-person standard, most did not know these 3 key facts.

More than 90% of African American and White men agreed that regular screening would help lower the number of deaths from prostate cancer. Although it seems reasonable that the general public would believe that early detection through screening leads to a decrease in cancer mortality, for PSA testing this belief is unproven.1–9 For some tests and cancers, studies53,54 have shown the assumption to be untrue. The fact that it is unclear whether regular PSA testing reduces mortality should be emphasized in public health campaigns and by health care providers because it provides a justification for requiring informed consent. Because it is unclear whether PSA testing reduces mortality from prostate cancer, men ought to learn the risks and benefits of testing before making a decision to screen.

More than 75% of African American and White men in our study believed that doctors are sure that the PSA test is a useful test. If men believe that screening with PSA reduces mortality and that doctors are sure that PSA testing is useful, it is unlikely that men would be motivated to learn the facts that would help them make an informed decision about screening.

Although 3 studies23,42,43 showed that African American men are less knowledgeable than White men about prostate cancer screening, none controlled for educational level. The authors42,43 concluded that educational efforts ought to be targeted to African Americans. In contrast, we found no differences in global knowledge between African American and White men after controlling for educational level and other covariates; however, we found that educational level was significantly associated with global knowledge after we controlled for other covariates. When we explored this association further by examining subsection knowledge scores, we found that educational level was significantly associated with knowledge about prostate cancer and treatment but not with knowledge about screening. This finding demonstrates that men are lacking in knowledge about prostate cancer screening regardless of their formal educational level or race/ethnicity. Our finding suggests that educational efforts ought to be targeted at men with less formal education regardless of race/ethnicity to increase knowledge and promote informed decisionmaking about screening.

We found that the experience of having heard about PSA testing modified the association between race/ethnicity and knowledge. Of men who had heard about PSA testing, African Americans were less knowledgeable than Whites, even after controlling for covariates. Among men who had been told by their physicians to have a PSA test or among those whose physicians had discussed the advantages and disadvantages of the PSA test, there were no differences in global knowledge between African American and White men. To reconcile these seemingly inconsistent findings, we suggest that White men may be learning about prostate cancer screening from sources other than their physicians. In studies examining knowledge among men participating in prostate cancer screening programs, Whites heard about screening from reading the newspaper,24,42 whereas African Americans heard about screening though radio42 or television.24 When listening to the radio or television, the audience is exposed to the information only once, often in summary; with print media, in contrast, readers can keep the information for later reference. It is also possible that people may remember certain facts more clearly after discussing them with people other than their physicians. Federman and colleagues19 found that of men who reported having had a PSA test, 38% reported that a wife, family member, or other person had influenced their decision. These hypotheses should be evaluated in future research studies.

We found that the experience of undergoing PSA testing modified the association between race/ethnicity and knowledge. The experience of undergoing PSA testing may involve health care provider–patient interactions that lead to improved knowledge regardless of race/ethnicity. This explanation would be consistent with previous studies42,43 showing that before an educational intervention, African Americans were less knowledgeable about prostate cancer screening than Whites and that afterward, knowledge was equivalent. But in contrast to such studies,42,43 which did not control for educational level, we found that even after we controlled for educational level, African Americans who reported never having had a PSA test were less knowledgeable than were Whites. It is possible that some White men may be using knowledge about PSA testing to make an informed decision not to screen. Although we tend to associate knowledge with making a “positive” decision to screen, it is just as appropriate to associate knowledge with making a “negative” decision against screening. In a study involving predominantly White men, Wolf and colleagues55 found that men who were given a scripted narrative about prostate cancer screening were less interested in PSA testing than were men who were given a single sentence.

Future studies may help assess the generalizability of our findings from a clinic-based population to other settings and populations, such as men attending mass screening programs. Future studies also may reveal the best way to promote informed decisionmaking for PSA testing. A public health campaign could begin with a rationale for informed decisionmaking by highlighting that it is not clear whether regular prostate cancer screening with PSA reduces mortality. Different approaches may need to be developed for people at different educational levels and may need to consider cultural factors and different sources of information. Such comprehensive public health efforts will become increasingly important for other screening tests. As technology improves and leads to the detection of disease at earlier stages, patients may be required to participate in informed decisionmaking more frequently. Weighing known risks against potential benefits will rest more on individual values, rather than on population-based data. As a result, public health campaigns will need to promote informed decisionmaking.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Cancer Institute grant K08-CA78615, awarded to Dr. Chan as a clinical scientist award, and by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Association of Schools of Public Health grant S1171–19/20. Additional technical support was provided by National Institutes of Health grant M01-RR02558 to the Clinical Research Center at The University of Texas–Houston.

This article was presented at the national meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, May 3, 2002.

E. C. Y. Chan conceived of the study, supervised all aspects of its implementation, and wrote the article. S. W. Vernon assisted with study conception by contributing to the study design and developing the analysis plan and reviewed drafts of the article. C. Ahn assisted with the analysis plan and completed the analyses. F. T. O’Donnell assisted with data collection and preliminary analysis. A. Greisinger and D. W. Aga assisted with the data collection. All authors helped to interpret findings and reviewed drafts of the article.

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the institutional review board of The University of Texas–Houston Health Sciences Center in Houston.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Burack RC, Wood DP Jr. Screening for prostate cancer. The challenge of promoting informed decision making in the absence of definitive evidence of effectiveness. Med Clin North Am. 1999;83:1423–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coley CM, Barry MJ, Fleming C, Fahs MC, Mulley AG. Early detection of prostate cancer, II: estimating the risks, benefits, and costs. American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:468–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coley CM, Barry MJ, Fleming C, Mulley AG. Early detection of prostate cancer, I: prior probability and effectiveness of tests. The American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:394–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolf SH. Screening for prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen: an examination of the evidence. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1401–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brawley OW. Prostate cancer screening: a note of caution. In: Thompson IM, Resnick MI, Klein EA, eds. Prostate Cancer Screening. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2001:175–185.

- 6.Gohagan JK, Prorok PC, Kramer BS, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial of the National Cancer Institute. J Urol. 1994;152:1905–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prorok P. The National Cancer Institute Multi-Screening Trial. Can J Oncol. 1994;4(suppl 1):98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroder FH. The European Screening Study for Prostate Cancer. Can J Oncol. 1994;4(suppl 1):102–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroder FH, Kranse R, Rietbergen J, et al. The European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC): an update. Eur Urol. 1999;35:539–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Urological Association. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) best practice policy. Oncology. 2000;14:267–272, 277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:915–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Family Physicians. Introduction to AAFP summary of policy recommendations for periodic health examination. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/x10601.xml. Accessed July 10, 2002. [PubMed]

- 13.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Von Eschenback AC, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:8–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coley CM, Barry MJ, Mulley AG. Screening for prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(6):480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prostate Cancer (PDQ): Screening. National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancerinfo/pdq/screening/prostate/HealthProfessional. Accessed January 30, 2003.

- 16.Braddock CJ III. Informed consent. In: Sugarman J, ed. Ethics in Primary Care. 20 Common Problems. New York: McGraw-Hill Health Professions Division; 2000:239–254.

- 17.President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Making Health Care Decisions: a Report on the Ethical and Legal Implications of Informed Consent in the Patient-Practitioner Relationship. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1982.

- 18.Katz J. The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. New York: Free Press; 1984.

- 19.Federman DG, Goyal S, Kamina A, Peduzzi P, Concato J. Informed consent for PSA screening: does it happen? Eff Clin Pract. 1999;2:152–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agho AO, Lewis MA. Correlates of actual and perceived knowledge of prostate cancer among African Americans. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24:165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mainous AG III, Hagen MD. Public awareness of prostate cancer and the prostate-specific antigen test. Cancer Pract. 1994;2:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Dell KJ, Volk RJ, Cass AR, Spann SJ. Screening for prostate cancer with the prostate specific antigen test. Are patients making informed decisions? J Fam Pract. 1999;48:682–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diefenbach PN, Ganz PA, Pawlow AJ, Guthrie D. Screening by the prostate-specific antigen test: what do patients know? J Cancer Educ. 1996;11:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demark-Wahnefried W, Strigo T, Catoe T, et al. Knowledge, beliefs, and prior screening behavior among blacks and whites reporting for prostate cancer screening. Urology. 1995;46:346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price JH, Colvin TL, Smith D. Prostate cancer: perceptions of African-American males. J Natl Med Assoc. 1993;85:941–947. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson SB, Ashley M, Haynes MA. Attitudes of African Americans regarding screening for prostate cancer. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88:241–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran WP, Cohen SJ, Preisser JS, Wofford JL, Shelton BJ, McClatchey MW. Factors influencing use of the prostate-specific antigen screening test in primary care. Am J Managed Care. 2000;6:315–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKnight JT, Tietze PH, Adcock BB, Maxwell AJ, Smith WO, Nagy MC. Screening for prostate cancer: a comparison of urologists and primary care physicians. South Med J. 1996;89:885–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawson DA, Simoes EJ, Sharp D, et al. Prostate cancer screening: a physician survey in Missouri. J Community Health. 1998;23:347–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fowler FJ Jr, Bin L, Collins MM, et al. Prostate cancer screening and beliefs about treatment efficacy: a national survey of primary care physicians and urologists. Am J Med. 1998;104:526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grove A. Taking on prostate cancer. Fortune. May 13, 1996:55–72.

- 32.Okie S. Annual PSA tests? Maybe not. Washington Post. May 28, 2002:HE03.

- 33.Weiss R. Controversy surrounds marketing of PSA test. Washington Post. May 23, 1995; special Health section:Z9.

- 34.Men’s Health Network. Prostate Cancer Stamp Resource Center. Available at: http://www.menshealthnetwork.org/prostate.html. Accessed March 28, 2003.

- 35.The Prostate Cancer Research Stamp Act of 1997. HR 2545. 105th Congress (1997).

- 36.Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. The US Postal Service and cancer screening—stamps of approval? N Engl J Med. 1999;340:884–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedrich MJ. Issues in prostate cancer screening. JAMA. 1999;281:1573–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 1999. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:8–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powell IJ. Prostate cancer and African American men. Oncology. 1997;11:599–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brawn PN, Johnson EH, Kuhl DL, et al. Stage at presentation and survival of white and black patients with prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;72:2569–2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Natarajan N, Murphy GP, Mettlin C. Prostate cancer in blacks: an update from the American College of Surgeons’ patterns of care studies. J Surg Oncol. 1989;40:232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barber KR, Shaw R, Folts M, et al. Differences between African American and Caucasian men participating in a community-based prostate cancer screening program. J Community Health. 1998;23:441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abbott RR, Taylor DK, Barber K. A comparison of prostate knowledge of African-American and Caucasian men: changes from prescreening baseline to postintervention. Cancer J Sci Am. 1998;4:175–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weinrich SP, Weinrich MC, Boyd MD, Atkinson C. The impact of prostate cancer knowledge on cancer screening. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:527–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashford AR, Albert SM, Hoke G, Cushman LF, Miller DS, Bassett M. Prostate carcinoma knowledge, attitudes, and screening behavior among African-American men in Central Harlem, New York City. Cancer. 2001;91:164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins M. Increasing prostate cancer awareness in African American men. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith GE, DeHaven MJ, Grundig JP, Wilson GR. African-American males and prostate cancer: assessing knowledge levels in the community. J Natl Med Assoc. 1997;89:387–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chan ECY, Sulmasy DP. What should men know about prostate specific antigen screening before giving informed consent? Am J Med. 1998;105:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994.

- 50.Faden RR, Beauchamp TL. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1986.

- 51.Sprung CL Winick BJ. Informed consent in theory and practice: legal and medical perspectives on the informed consent doctrine and a proposed reconceptualization. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:1346–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000.

- 53.Parkin DM, Moss SM. Lung cancer screening: improved survival but no reduction in deaths—the role of “overdiagnosis.” Cancer. 2000;89:2369–2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woods WG, Gao RN, Shuster JJ, et al. Screening of infants and mortality due to neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1041–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolf AMD, Nasser JF, Wolf AM, Schorling JB. The impact of informed consent on patient interest in prostate-specific antigen screening. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1333–1336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]