Abstract

Objective. We identified the prevalence and types of violence experienced by pregnant women, the ways victimization changed during pregnancy from the year prior to pregnancy, and factors associated with violence during pregnancy.

Methods. We interviewed 914 pregnant women treated in health clinics in Mexico about violence during and prior to pregnancy, violence during childhood and against their own children, and other socioeconomic indicators.

Results. Approximately one quarter of the women experienced violence during pregnancy. The severity of emotional violence increased during pregnancy, whereas physical and sexual violence decreased. The strongest predictors of abuse were violence prior to pregnancy, low socioeconomic status, parental violence witnessed by women in childhood, and violence in the abusive partner’s childhood. The probability of violence during pregnancy for women experiencing all of these factors was 61%.

Conclusions. Violence is common among pregnant women, but pregnancy does not appear to be an initiating factor. Intergenerational violence is highly predictive of violence during pregnancy.

Violence against women has drawn the attention of researchers and policymakers in many fields, from social to judicial to medical disciplines. This subject has been studied for at least 20 years in North America and Europe, and since the late 1990s in Mexico.1–3

Violence against women has become a top priority on the agendas of many international health organizations.4–6 The Pan American Health Organization has estimated that women lose an average of 1 out of 5 days of healthy life during their reproductive years because of violence.7 Scientists have stressed that compared with nonbattered women, victims of violence are more likely to use the medical system and to seek help at emergency rooms (for reasons related to the abuse as well as other unspecified reasons), to take prescription drugs, to become addicted to alcohol or drugs, and to require psychiatric treatment.8–10

Research into the causes of violence toward women has found that violent experiences in childhood, violent experiences in intimate partnerships, and violence perpetrated against children are highly correlated.11–14 The patterns of violence that are repeated from one generation to the next are becoming a central issue in violence research.11,12 Although available evidence suggests that the majority of individuals who have been abused as children will not become abusive parents,13 research findings indicate that those abused in childhood or adolescence are more likely to be abused as adults and to become abusers.14 Other research shows that men who are violent toward their partners exhibit different personality characteristics than do nonviolent men, and that these differences are highly correlated with having experienced childhood violence.15 Witnessing interparental violence has also proved to have serious consequences in the development of an adult’s role of aggressor or victim, due perhaps to the internalization of violence as an acceptable means of resolving problems.16–18 Additionally, it has been shown that the presence of 1 type of violence is a strong predictor for other types.19

For most abused women, physical violence does not seem to be initiated during pregnancy,20 but some studies have shown that physical abuse prior to pregnancy is a strong predictor of physical abuse during pregnancy.21 Moreover, women reporting abuse both before and during pregnancy also report greater severity of abuse than do women abused only before pregnancy or only during pregnancy.22 The prevalence of abuse during gestation varies according to the definitions of violence, the way violence is measured, and the study population. Thus, the international literature reports prevalence values that range from 4% to 25%.23–28

In Mexico, few studies on violence against women have examined violence against pregnant women. Although there is still much research to be done, several regional studies have found that the prevalence of violence against women in general varies from 20% to 40%29–32 and that this violence has serious effects on women’s health.33,34 The only study to examine the relationship between violence and pregnancy in a general population in Mexico found a prevalence of 33.5%.35 No studies have examined the association between a history of violent victimization and violence during pregnancy.

In this study we examined a large sample of women in the last trimester of pregnancy treated at several health clinics in the state of Morelos, Mexico. We had 3 objectives: (1) to identify the prevalence and types of violence experienced by pregnant women, (2) to identify how victimization changed during pregnancy from the year leading up to pregnancy, and (3) to identify factors relating to previous violence that are associated with violence during pregnancy. We hope this article contributes to filling the void that some authors have encountered in this field of knowledge.36,37

METHODS

Study Sample

Throughout 1998 and 1999, we surveyed women in the third trimester of pregnancy who attended 27 prenatal health clinics in the state of Morelos, Mexico, maintained by the Morelos Ministry of Health (MMOH) and the Mexican Institute for Social Security (MISS). The MMOH serves a primarily uninsured, low-income population, and the MISS serves a primarily salaried, middle-income population. This survey focused on the cities of Cuernavaca and Cuautla, which, owing to the size of their populations (337 000 inhabitants in Cuernavaca, 153 000 in Cuautla) and the concentration of economic activities, are the 2 most important in the state and have the largest concentrations of prenatal consultations.38,39

We interviewed 468 women in the MMOH clinics and 446 women in the MISS clinics, for a total sample of 914 women. This corresponds to a power exceeding 85%.

Study Protocol

We recruited women during routine prenatal exams. The women were interviewed privately, without their partners, by trained nurses and social workers in each clinic. Interviews lasted an average of 40 minutes. Participants were informed that their responses would be confidential and that no financial incentive would be offered for participation. Fewer than 1% of women refused to participate in the survey. For this analysis, only women who had been with their current partners for 1 full year prior to the pregnancy were included.

The interviewers administered a questionnaire that asked about demographic and socioeconomic indicators for each woman and her partner, any history of violence in childhood for herself or her partner, violent victimization during the current pregnancy, violence in the 12 months before this pregnancy, and violence toward the woman’s children by herself or her partner.

Because Mexico does not have violence reporting laws, interviewers were not required to report violent activity. However, in any instance of abuse, women were offered a referral to social services. Socioeconomic status was measured ecologically according to the clinic attended.

Measuring Violence Victimization

To ascertain the type and frequency of violence during pregnancy, we adapted a series of actions describing violent events from the Index of Spouse Abuse40 and the Severity of Violence Against Women Scale.41 The final tool included 26 items, of which 12 related to physical violence, 11 to emotional violence, and 3 to sexual violence (see note to Table 1 ▶). The instrument was developed and administered in Spanish. For each item, women were asked whether they had experienced this event never, once, several times, or many times. These instruments were previously tested in Mexico with successful results.2

TABLE 1—

Number, Proportion, and Mean Severity of Violence Before and During Pregnancy

| Before Pregnancy | During Pregnancy | ||||||

| Number Experiencing Violence | Prevalence of Violence, % | Mean Severity (SD) | Number Experiencing Violence | Prevalence of Violence, % | Mean Severity (SD) | Difference in Mean Severitya | |

| Total sample (n = 914) | |||||||

| Any violence | 223 | 24.4 | 4.4 (12.7) | 224 | 24.5 | 4.1 (11.8) | −0.35 |

| Physical violence | 111 | 12.1 | 1.7 (5.8) | 97 | 10.6 | 1.2 (4.4) | −0.47*** |

| Emotional violence | 166 | 18.2 | 2.0 (6.1) | 187 | 20.5 | 2.3 (6.5) | 0.29* |

| Sexual violence | 91 | 10.0 | 0.8 (2.7) | 74 | 8.1 | 0.6 (2.5) | −0.16** |

| Sample with any violence during pregnancy (n = 224) | |||||||

| Any violence | 152 | 67.9 | 14.6 (20.4) | 224 | 100 | 16.7 (18.9) | 2.2* |

| Physical violence | 79 | 35.3 | 5.4 (10.0) | 97 | 43.3 | 4.8 (7.8) | −0.6 |

| Emotional violence | 122 | 54.5 | 6.8 (9.8) | 187 | 83.5 | 9.4 (10.4) | 2.6*** |

| Sexual violence | 65 | 29.0 | 2.4 (4.4) | 74 | 33.0 | 2.5 (4.5) | 0.1 |

Note. The final tool included 12 items related to physical violence (Has your partner purposely pushed you; shaken, jerked, or pulled you; twisted your arm; hit you with a hand or fist; kicked you; hit you in the abdomen; thrown an object at you; hit you with a stick, belt, or a domestic object; tried to choke you; attacked you with a switchblade, knife, or machete; shot you with a gun or rifle; or attacked you with anything else?), 11 items related to emotional violence (Has your partner humiliated or scorned you; insulted you; become jealous or suspicious of your friends; told you you were unattractive or ugly; hit or kicked the wall or a piece of furniture; destroyed your things; threatened to hit you; threatened you with a switchblade, knife, or machete; threatened you with a gun or rifle; made you feel frightened of him or her; or threatened to kill you or himself/herself?), and 3 items related to sexual violence (Has your partner demanded sex when you were not willing; threatened to have sex with other women if you did not consent to have sex; or used physical force to have sex with you against your will?).

aA negative number indicates that the mean severity level decreased.

*P < .10; **P < .05; ***P < .01. Results are 1-tailed.

To develop an index of violence severity, we needed to assign weights to each of the 26 items. We determined weights by surveying 120 women, who were asked to rate the severity of each item on a scale of 1 to 100. These 120 women were not participants in the abuse survey and were sampled from both occupational and clinical settings, with the intention of providing a wide representation of Mexican women. We averaged their responses to create a severity weight for each item.

To calculate an index of severity for each study subject, we multiplied the weight of each item by the frequency with which the event was experienced (never = 0; once = 1; several times = 2; many times = 3). We then summed these weight-by-frequency scores to create a severity index for emotional, physical, sexual, and overall violence. The methodology and validation of this weighting system is described in detail elsewhere.42,43

For this analysis, we normalized index scores to a scale of 0 to 100, in which a score of 100 would indicate that every type of abuse was experienced frequently (note that, because the scales were normalized to this sample, a different sample would yield a different standard for normalizing scores). Although no women reported such frequent abuse, this scaling provided a numerical system that more clearly captured the scope of the index. The range of abuse severity on the normalized scale was 0 to 32.4.

Analysis

We estimated the prevalence of violence as the number of women reporting any level of abuse divided by the entire sample. We measured the mean severity of violence as the average of the severity index. We used paired t tests to observe differences in the mean severity of violence before and during pregnancy. We divided P values into those less than .01, those equal to .01 but less than .05, and those equal to .05 but less than .10. On the basis of the α values we used for our power and sample size calculations, a P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. We ran statistical tests with SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill).

We used the log binomial model to estimate prevalence ratios with the PROC GENMOD feature of SAS (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).44 The log binomial model allows direct estimation of prevalence ratios when the odds ratio is not a good estimate of the prevalence ratio. We first estimated prevalence ratios for sociodemographic variables in bivariate and multivariate models using “none” versus the presence of any level of violence during pregnancy as the dichotomous dependent variable. We then included factors in the multivariate analysis that were significant at the P = .10 level (socioeconomic status, woman’s age, woman’s educational status) to control for confounding in log binomial models examining violence-related factors. Because violence-related factors were highly correlated, we examined each factor in individual models in which we controlled for significant socioeconomic indicators.

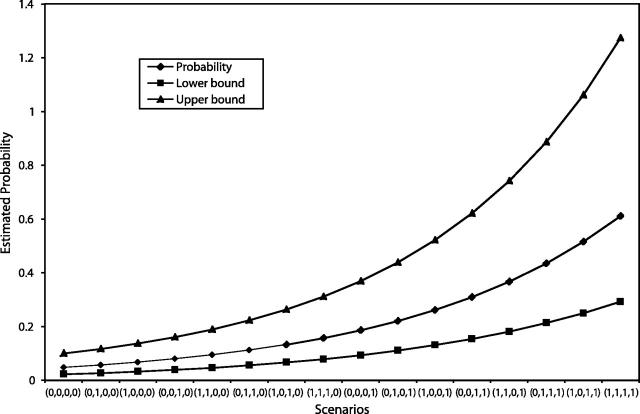

When conducting bivariate analyses, we were struck by the strong association between variables measuring previous violence and those measuring violence during pregnancy. To describe the influence of previous violence on violence during pregnancy, we ran an additional model using the strongest multivariate predictors of violence during pregnancy among the following independent variables: (1) any abuse by the partner in the year prior to pregnancy, (2) physical or emotional abuse during the woman’s and partner’s childhoods, (3) the witnessing of domestic violence by the woman as a child, (4) any reported abuse of children by the woman or her partner, and (5) sociodemographic variables. We used model-fit statistics to identify 4 independent predictors of violence during pregnancy and retained only significant variables.

We used estimates from this model to calculate the increased risk for the combination of these 4 factors. We created these risk scenarios by estimating the Cartesian product of significant variables in all categories and depicting them as a cumulative risk curve. The Cartesian product is the cumulative value of n-dimensional vectors, such that the first entry is an element of the first set, the second entry is an element of the second set, and so on. Our analysis contained 4 dimensions, and we calculated products as increasing risk for each permutation of responses from these 4 dimensions. These calculations were based on the log link function.

RESULTS

Description of the Study Sample

Of the 914 women interviewed, 51% were seen in MMOH clinics and 49% in MISS clinics; 48% were interviewed in Cuautla and 52% in Cuernavaca. The average age of the women was 25 years (SD = 5.5) and that of their partners was 28 years (SD = 7.8). The average number of years of schooling for women and their partners was 8.56 years (SD = 3.5) and 8.21 years (SD = 4.2), respectively. We found a statistically significant difference in the level of schooling among partners (t = 2.49; P < .05). The average number of children was 1.12 (SD = 1.3).

Prevalence and Severity of Violence Before and During Pregnancy

The prevalence of overall violence was very similar before and during pregnancy (24.4% and 24.6%, respectively), with no statistically significant difference (χ2 = 0.0118; P > .05). Similarly, we detected no significant differences when examining the prevalence of the 3 types of violence (emotional, physical, sexual). Thus, the prevalence measure does not indicate a change in violence with pregnancy (Table 1 ▶).

When we used the violence index constructed for this research, however, the dynamics of violence before and during pregnancy showed significant trends (Table 1 ▶). Because approximately 24% of the women reported violence, about 76% of the respondents in the total sample have a severity index of 0. Thus, the severity index among the total population is low, and the distribution is highly skewed. The large standard errors arise from the few women who had very high index scores.

For all women, the severity index for physical and sexual violence decreased significantly, whereas emotional violence increased significantly at the P < .10 level. The change in overall violence was not significant, probably because it represented a weighted average of the 3 types of abuse, each of which showed different trends. When we examined only women who reported some level of violence during pregnancy, we saw a significant increase in overall violence. The overall increase was due entirely to a large and significant increase in emotional violence, because neither physical nor sexual violence changed significantly.

Variables Associated With Violence During Pregnancy

Table 2 ▶ shows demographic variables in relation to violence during pregnancy. Younger women and younger partners were both associated with an increased prevalence of violence during pregnancy. Being a housewife was associated with increased abuse among women, and being unemployed or a bluecollar worker was associated with increased abuse by the partner. Not having completed primary school was significantly associated with abuse victimization among women but not abuse perpetration among men. Women of low socioeconomic status (measured ecologically as clinic service) had 2.31 times the risk for violence during pregnancy of women of middle socioeconomic status.

TABLE 2—

Prevalence of Violence and Association With Violence During Pregnancy by Demographic Factors

| Variable | No Violence During Pregnancy, No. (%) | Violence During Pregnancy, No. (%) | Prevalence Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

| Woman’s age, y | |||

| ≥ 30 | 137 (77.8) | 39 (22.2) | 1.00 |

| 20–29 | 440 (77.2) | 130 (22.8) | 1.19 (0.82, 1.74) |

| < 20 | 113 (67.3) | 55 (32.7) | 1.57 (1.02, 2.41) |

| Partner’s age, y | |||

| ≥ 30 | 236 (77.1) | 70 (22.9) | 1.00 |

| 20–29 | 384 (76.6) | 117 (56.0) | 1.12 (0.83, 1.51) |

| < 20 | 31 (58.5) | 22 (41.5) | 1.85 (1.16, 2.96) |

| Woman’s occupation | |||

| Employed or student | 176 (83.0) | 36 (17.0) | 1.00 |

| Housewife | 514 (73.2) | 188 (26.8) | 1.56 (1.09, 2.24) |

| Partner’s occupation | |||

| Professional | 288 (80.0) | 72 (20.0) | 1.00 |

| Blue-collar worker/unemployed | 362 (72.7) | 136 (27.3) | 1.49 (1.11, 1.99) |

| Woman’s education | |||

| Completed primary or more | 606 (77.1) | 180 (22.9) | 1.00 |

| Less than primary | 57 (63.3) | 33 (36.7) | 1.78 (1.28, 2.49) |

| Partner’s education | |||

| Completed primary or more | 559 (76.6) | 171 (23.4) | 1.00 |

| Less than primary | 53 (67.9) | 25 (32.1) | 1.28 (0.84, 1.94) |

| Socioeconomic level | |||

| Medium | 379 (85.0) | 67 (15.0) | 1.00 |

| Low | 311 (66.5) | 157 (33.6) | 2.31 (1.73, 3.07) |

All variables describing violence throughout the lives of the woman and her partner were significant predictors of violence during pregnancy when we controlled for sociodemographic factors (Table 3 ▶). Compared with women who experienced no violence in the year prior to pregnancy, women who experienced violence prior to pregnancy were 9.47 times more likely to be abused during pregnancy (95% confidence interval [CI] = 7.13, 12.57). This is consistent with our finding that the prevalence of violence is similar before and during pregnancy. This strong relationship between prior violence and current violence during pregnancy also indicates that pregnancy is rarely an initiating factor for violence.

TABLE 3—

Association Between History of Violence and Violence During Pregnancy, Controlled for Woman’s Age, Education, and Socioeconomic Status

| Variable | No Violence During Pregnancy, No. (%) | Violence During Pregnancy, No. (%) | Prevalence Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)a |

| Abuse prior to pregnancy | |||

| No abuse | 620 (89.6) | 72 (10.4) | 1.00 |

| Abuse | 70 (31.5) | 152 (68.5) | 9.47 (7.13, 12.57) |

| Physical abuse in woman’s childhood | |||

| Absent or low | 319 (85.5) | 54 (14.5) | 1.00 |

| Moderate or high | 365 (68.6) | 167 (31.4) | 2.33 (1.70, 3.19) |

| Physical abuse in partner’s childhood | |||

| Absent or low | 223 (85.1) | 39 (14.9) | 1.00 |

| Moderate or high | 263 (69.4) | 116 (30.6) | 1.89 (1.44, 2.48) |

| Emotional abuse in woman’s childhood | |||

| Absent or low | 521 (83.4) | 104 (16.6) | 1.00 |

| Moderate or high | 157 (58.4) | 112 (41.6) | 2.75 (2.14, 3.53) |

| Emotional abuse in partner’s childhood | |||

| Absent or low | 285 (85.8) | 47 (14.2) | 1.00 |

| Moderate or high | 139 (65.0) | 75 (35.0) | 2.91 (2.05, 4.16) |

| Woman witnessed violence at home | |||

| No | 432 (83.1) | 88 (16.9) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 237 (64.4) | 131 (35.6) | 2.39 (1.82, 3.14) |

| Woman physically abuses children | |||

| No | 150 (84.7) | 27 (15.3) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 259 (69.4) | 114 (30.6) | 2.78 (1.72, 4.48) |

| Partner physically abuses children | |||

| No | 281 (80.1) | 70 (19.9) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 120 (65.2) | 64 (34.8) | 1.97 (1.42, 2.72) |

| Woman emotionally abuses children | |||

| No | 348 (77.3) | 102 (22.7) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 61 (61.6) | 38 (38.4) | 1.70 (1.21, 2.40) |

| Partner emotionally abuses children | |||

| No | 379 (79.3) | 99 (20.7) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 23 (39.0) | 36 (61.0) | 3.54 (2.64, 4.76) |

aAll models control for woman’s age, education, and socioeconomic status, measured ecologically by institution.

Experiencing or witnessing violence during childhood was strongly associated with violence during pregnancy. The risk was slightly higher for both childhood physical abuse and childhood emotional abuse against the woman than for such abuse against her partner. For both women and men, emotional abuse posed a greater risk than physical abuse. Witnessing violence at home was strongly associated with later abuse during pregnancy, with a prevalence ratio of 2.39 (95% CI = 1.82, 3.14). Abuse toward children showed the strongest association with abuse during pregnancy when the partner emotionally abused children.

We entered these variables into a multivariate model to identify the strongest independent associations with violence during pregnancy (Table 4 ▶). Independent predictors of violence during pregnancy included socioeconomic status, violence during the year prior to the pregnancy, violence witnessed by the woman in her home as a child, and violence experienced by the partner as a child. Even when we controlled for other types of violence, women who witnessed violence in their childhood homes and men who were abused as children had a significantly higher prevalence of abuse (victimization vs perpetration) during pregnancy compared with women and men who did not share these experiences.

TABLE 4—

Violence Factors Associated With Violence During Pregnancy, Forward Likelihood Selection

| Variable | Prevalence Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

| Socioeconomic statusa | 1.24 (1.01, 1.58) |

| Violence before pregnancy | 7.84 (5.75, 10.68) |

| Woman witnessed violence in childhood | 1.28 (1.70, 3.19) |

| Partner was abused during childhood | 7.03 (1.20, 12.55) |

aSocioeconomic status is measured ecologically by institution.

Figure 1 ▶ depicts the increasing adjusted probabilities of abuse during pregnancy represented by each combination, or scenario, of the 4 predictive variables in the multivariate model. The cell sizes for each scenario ranged from 10 to 153. Upper and lower boundaries are shown for each scenario. The model predicts the lowest probabilities of experiencing violence during pregnancy (P = .05) in the case of women who are middle class, who did not experience violence during the year prior to the pregnancy or witness interparental violence during childhood, and whose male partners were not abused during childhood. The highest probabilities of experiencing violence during pregnancy coincided with low socioeconomic status and the presence of all types of violence (P = .61). This probability indicates that 61% of women with this risk scenario experience violence during pregnancy.

FIGURE 1—

Adjusted conditional estimated probabilities of suffering abuse during pregnancy, based on final log binomial model.

Note. The first digit indicates socioeconomic status, as measured ecologically by institution (0 = medium; 1 = low). The second digit indicates degree of violence during previous years (0 = none/low; 1 = medium/severe). The third digit indicates whether the woman witnessed interparental violence in childhood (0 = no; 1 = yes). The fourth digit indicates whether the male partner was abused during childhood (0 = no; 1 = yes). The first point represents no violence and medium socioeconomic status (0:0:0:0).

DISCUSSION

According to some authors, the special vulnerability of pregnant women both demands and provides opportunities for research into interventions that seek to better identify, prevent, and treat the problem of violence against women in general.45,46 This topic has been studied only indirectly among Mexican populations.35

In this sample, approximately one quarter of women reported some level of abuse prior to or during pregnancy. Emotional violence (roughly 20% prevalence) was more prevalent than physical and sexual violence (approximately 10% prevalence). These data are very similar to those reported in a recent study carried out in another city in Mexico.29

For all women, and especially for women who experienced violence during pregnancy, emotional abuse increased over the course of pregnancy, whereas physical and sexual violence generally decreased. We can hypothesize that the increased severity of emotional violence during pregnancy may owe to the reduced sexual availability of pregnant women or to concern about or stigma against physically injuring a pregnant woman. Thus, faced with their partner’s pregnancy, abusive men might reduce their level of physical and sexual violence but increase their use of emotional abuse such as insults, threats, and humiliation. These findings illustrate the importance of measuring emotional violence as well as physical violence when conducting research on partner abuse.

Variables describing violence in the lives of the women and their partners were highly associated with violence during pregnancy. The strong association between violence before and during pregnancy has been previously documented.22,28 However, even when we controlled for violence prior to pregnancy, witnessing violence in the home as a child (for the woman) and being abused as a child (for the partner) were significantly associated with violence victimization and violence perpetration, respectively, during pregnancy. This is clear evidence that intimate partner violence is not an independent phenomenon but is strongly tied to violence during childhood. Emotional abuse during childhood was more strongly associated with abuse during pregnancy than was physical abuse, suggesting the potential role of emotional abuse in learned behavior. Taken together, these findings strongly indicate that a large component of violence in adult relationships is learned during childhood.

The risk of violence for women who have all of these experiences is high (P = .61). Identifying the various risk scenarios is a fundamental step toward developing efficacious interventions for identification, prevention, and treatment of violence against pregnant women. The urgency of the need for such interventions has been repeatedly stressed in the literature.25,27 In fact, as a response to these findings, the first author became involved in preparing a manual for health care providers aimed at promoting guidelines for the management and referral of maltreated women.47 This manual has become especially important given the recent change of guidelines of health services in Mexico. These new norms explicitly identify standard criteria for health delivery and the training that must be provided to those who deliver services to abuse victims, including pregnant women.48

Although this analysis presents important information about violence during pregnancy, the study does have some limitations. Information about violence is self-reported, which may lead to recall bias. Women were asked to report about their own and their partners’ experiences with abuse during childhood. Women who currently experience abuse may be more likely to remember abuse as a child and may be more likely to question their partners to find reasons for the current abuse. This bias would lead to an increase in the observed effect. In addition, although all efforts were made to create a comfortable environment and to assure participants that their responses would be confidential, women may have been reluctant to report abuse against their children by either themselves or their partners.

The study sample was drawn from 27 clinics maintained by 2 different agencies in Mexico that serve 2 different populations. The analysis controlled for differences between the 2 agencies that maintain the clinics. We found no significant differences in the prevalence of abuse or sociodemographic characteristics of women within clinics served by each agency and so did not incorporate cluster analysis. Our having omitted a cluster analysis could possibly lead to an underestimate of standard error and artificially narrow CIs.

In Mexico, research into the problem of violence against women during pregnancy is in its infancy. Further research—preferably population-based studies, to corroborate and refine the findings reported here—is necessary. Research examining violence during the postpartum period should be incorporated into studies examining violence before and during pregnancy, especially because the postpartum period begins the infant’s lifetime exposure to violence.49 It is also crucial to develop innovative methods to examine the dynamics of the family and the generational potential for violence.50 One aspect of this research must focus on the men who commit violence. Interventions that reduce the use of violence by men and the violent behavior that is learned in childhood are urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Southern California Injury Prevention Research Center at the University of California Los Angeles (R49 CCR 903622 from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and by the Mexican National Council for Science and Technology (11312-M).

We are grateful to Dr Jess F. Kraus, Director of the Injury Prevention Research Center, for his valuable support and advice throughout the development of this project. The authors would like to thank Rosa Lilia Alvarez, Luz Maria Arenas, Andres Menjivar, Paloma Rodriguez, and Rosario Valdez for their valuable collaboration in the data collection process.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Regional Centre of Multidisciplinary Research, the Mexican Ministry of Health, and the Mexican Institute for Social Security. Informed consent was obtained from each woman interviewed.

Contributors

R. Castro planned the study, coordinated the study in Morelos, and designed the questionnaire and the data analysis. C. Peek-Asa planned the study, coordinated a collaborative study in California (results of which are not reported here), supervised data analysis, and contributed to the writing of this article. A. Ruiz assisted with both the data analysis and the writing of the article.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Ramírez-Rodríguez JC, Uribe-Vázquez G. Mujer y violencia: un hecho cotidiano. Salud Pública Mex. 1993;35:148−160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asociación Mexicana contra la Violencia hacia las Mujeres. Encuesta de Opinión Pública sobre la Incidencia de Violencia Familiar. Mexico City, Mexico: Asociación Mexicana contra la Violencia hacia las Mujeres; 1995.

- 3.Riquer F, Saucedo I, Bedolla P. Violencia hacia la mujer: un asunto de salud pública. In: Langer A, ed. La Salud de la Mujer Mexicana. Mexico City, Mexico: The Population Council; 1996:247–287.

- 4.United Nations. Reporte Preliminar de la IV Conferencia Mundial sobre la Mujer y Desarrollo, Beijing, China. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations; 1995.

- 5.Organization of American States. Convención Interamericana para Prevenir, Sancionar y Erradicar la Violencia contra la Mujer [“Convention of Belém do Pará”]. Washington, DC: Inter-American Commission of Women, General Secretariat of the Organization of American States; 2000.

- 6.Pan American Health Organization. Declaración de la Conferencia Interamericana sobre Sociedad, Violencia y Salud. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 1994.

- 7.Heise L, Pitanguy J, Germain A. Violencia contra la Mujer: La Carga Oculta sobre la Salud. Washington, DC: World Bank; 1994.

- 8.Stark E, Flitcraft A. Spouse abuse. In: Rosenburg ML, Fenley MA, eds. Violence in America: A Public Health Approach. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1991:140–165.

- 9.Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. Violence against women: relevance for medical practitioners. JAMA. 1992;267:3184–3189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cokkinides VE, Coker AL, Sanderson M, Addy C, Bethea L. Physical violence during pregnancy: maternal complications and birth outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;95(5 pt 1):661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappell C, Heiner RB. The intergenerational transmission of family aggression. J Fam Violence. 1990;5:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doumas D, Margolin G, John RS. The intergenerational transmission of aggression across three generations. J Fam Violence. 1994;9:157–175. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaufman J, Zigler E. Do abused children become abusive parents? Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rixey S. Family violence and the adolescent. Md Med J. 1994;43:351–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett OW, Hamberger LK. The assessment of maritally violent men on the California Psychological Inventory. Violence Vict. 1992;7:15–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to interparental violence in childhood and psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:339–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milner JS, Robertson KR, Rogers DL. Childhood history of abuse and adult child abuse potential. J Fam Violence. 1990;5:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sternberg KJ, Lamb ME, Greenbaum C, et al. Effects of domestic violence on children’s behavior problems and depression. Dev Psychol. 1993;29:44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomison AM. Exploring Family Violence: Links Between Child Maltreatment and Domestic Violence. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Institute of Family Studies, National Child Protection Clearinghouse; 2000. Issues in Child Abuse Prevention paper 13.

- 20.Moore M. Reproductive health and intimate partner violence. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:302–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin SL, Mackie L, Kupper LL, Buescher PA, Moracco KE. Physical abuse of women before, during, and after pregnancy. JAMA. 2001;285:1581–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McFarlane J, Parker B, Soeken K, Silva C, Reed S. Severity of abuse before and during pregnancy for African American, Hispanic, and Anglo women. J Nurse Midwifery. 1999;44:139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helton AS, McFarlane J, Anderson ET. Battered and pregnant: a prevalence study. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:1337–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bullock LF, McFarlane J. The birth-weight/battering connection. Am J Nurs. 1989;89:1153–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McFarlane J. Battering during pregnancy: tip of an iceberg revealed. Women Health. 1989;15:69–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bewley CA, Gibbs A. Violence in pregnancy. Midwifery. 1991;7:107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gazmararian JA, Lazorick S, Spitz AM, Ballard TJ, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA. 1996;275:1915–1920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hedin LW, Grimstad H, Moller A, Schei B, Janson PO. Prevalence of physical and sexual abuse before and during pregnancy among Swedish couples. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:310–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Sotelo J. Domestic violence in Mexico. JAMA. 1997;275:1937–1941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramírez Rodríguez JC, Patiño Guerra MC. Mujeres de Guadalajara y violencia doméstica: resultados de un estudio piloto. Cadernos Saúde Publica. 1996;12(3):405–409. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvaro-Zaldivar G, Salvador-Moysen J, Estrada-Martinez S, Terrones-Gonzalez A. Prevalencia de violencia doméstica en la ciudad de Durango. Salud Pública Mex. 1998;40:481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramírez RJC, Patiño GMC. Algunos aspectos sobre la magnitud y trascendencia de la violencia doméstica contra la mujer: un estudio piloto. Salud Men. 1997;20(2):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkler K. Gender, domestic violence and sickness in Mexico. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1147–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lozano R, Hijar M, Torres JL. Violencia, seguridad publica y salud. In: Frenk J, ed. Observatorio de la Salud: Necesidades, Servicios, Politicas. Mexico City, Mexico: Fundación Mexicana para la Salud; 1997:83–115.

- 35.Valdez-Santiago R, Sanin-Aguirre LH. La violencia doméstica durante el embarazo y su relación con el peso al nacer. Salud Pública Mex. 1996;38:352–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gazmararian JA, Petersen R, Spitz AM, Goodwin MM, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Violence and reproductive health: current knowledge and future research directions. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMahon PM, Goodwin MM, Stringer G. Sexual violence and reproductive health. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:121–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. Anuario Estadistico del Estado de Morelos. Mexico City, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática; 1997.

- 39.Aguayo Quezada S. El Almanaque Mexicano. Mexico City, Mexico: Grijalbo; 2000.

- 40.Hudson W, McIntosh S. The assessment of spouse abuse: two quantifiable dimensions. J Marriage Fam. 1981;43:873–888. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marshall L. Development of the Severity of Violence Against Women scales. J Fam Violence. 1992;7:103–121. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peek-Asa C, Garcia L, McArthur D, Castro R. Severity of intimate partner abuse indicators as perceived by women in Mexico and the United States. Women Health. 2002;35:165–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castro R, Garcia L, Peek-Asa C, Ruiz G. Developing an index to measure violence against women for comparative studies between Mexico and the United States. J Fam Violence. In press.

- 44.Skov T, Deddens J, Petersen MR, Endahl L. Prevalence proportion ratios: estimation and hypothesis testing. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell JC, Moracco KE, Saltzman LE. Future directions for violence against women and reproductive health: science, prevention, and action. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiist WH, McFarlane J. Severity of spousal and intimate partner abuse to pregnant Hispanic women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:248–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elu MC, Santos E, Valdez R, et al. Carpeta de Apoyo para la Atención en los Servicios de Salud de Mujeres Embarazadas Víctimas de Maltrato. Mexico City, Mexico: Comité Promotor por una Maternidad sin Riesgos en México; 2000.

- 48.Secretaría de Salud. Prestación de servicios de salud. Criterios para la atención médica de la violencia familiar. Diario Oficial de la Federación; March 8, 2000. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-190-SSA1-1999.

- 49.Hedin LW. Postpartum, also a risk period for domestic violence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;89:41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKinlay JB. A case for refocusing upstream: the political economy of illness. In: Conrad P, Kern R, eds. The Sociology of Health and Illness: Critical Perspectives. 2nd ed. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press; 1986:484–489.