THE GREAT MORTALITY AMONG CHILDREN of the working class, and especially among those of the factory operatives, is proof enough of the unwholesome conditions under which they pass their first years. These influences are at work, of course, among the children who survive, but not quite so powerfully as upon those who succumb. The result in the most favourable case is a tendency to disease, or some check in development, and consequent less than normal vigour of the constitution. A nine-year-old child of a factory operative that has grown up in want, privation, and changing conditions, in cold and damp, with insufficient clothing and unwholesome dwellings, is far from having the working strength of a child brought up under healthier conditions. At nine years of age it is sent into the mill to work 61/2 hours (formerly 8, earlier still, 12 to 14, even 16 hours) daily, until the thirteenth year; then twelve hours until the eighteenth year. The old enfeebling influences continue, while the work is added to them. . . . but in no case can its [the child’s] presence in the damp, heavy air of the factory, often at once warm and wet, contribute to good health; and, in any case, it is unpardonable to sacrifice to the greed of an unfeeling bourgeoisie the time of children which should be devoted solely to their physical and mental development, and to withdraw them from school and the fresh air in order to wear them out for the benefit of the manufacturers. . . .

The [Factory Inquiry of 1833] Commissioners mention a crowd of cripples who appeared before them, who clearly owed their distortion to the long working hours. This distortion usually consists of a curving of the spinal column and legs. . . . I have seldom traversed Manchester without meeting three or four . . . [cripples], suffering from precisely the same distortions of the spinal columns and legs . . . and I have often been able to observe them closely. I know one personally who . . . got into this condition in Mr. Douglas’s factory in Pendleton, an establishment which enjoys an unenviable notoriety among the operatives by reason of the former long working periods continued night after night. It is evident, at a glance, whence the distortions of these cripples come, they all look exactly alike. The knees are bent inward and backwards, the ankles deformed and thick, and the spinal column often bent forwards or to one side. . . .

In cases in which a stronger constitution, better food, and other more favourable circumstances enabled the young operative to resist this effect of a barbarous exploitation, we find, at least, pain in the back, hips, and legs, swollen joints, varicose veins, and large, persistent ulcers in the thighs and calves. These afflictions are almost universal among the operatives. . . .

All these afflictions are easily explained by the nature of factory-work, which is, as the manufacturers say, very “light,” and precisely by reason of its lightness, more enervating than any other. The operatives have little to do, but must stand the whole time. Any one who sits down, say upon a window-ledge or a basket, is fined, and this perpetual upright position, this constant mechanical pressure of the upper portions of the body upon spinal column, hips, and legs, inevitably produces the results mentioned. This standing is not required by the work itself, and at Nottingham chairs have been introduced, with the result that these maladies disappeared. . . . This long protracted upright position, with the bad atmosphere prevalent in the mills entails, besides the deformities mentioned, a marked relaxation of all vital energies, and, in consequence, all sorts of other afflictions general rather than local. The atmosphere of the factories is, as a rule, at once damp and warm, far warmer than is necessary, and, when the ventilation is not very good, impure, heavy, deficient in oxygen, filled with dust and the smell of the machine oil, which almost everywhere smears the floor, sinks into it, and becomes rancid. The operatives are lightly clad by reason of the warmth, and would readily take cold in case of irregularity of the temperature; a draught is distasteful to them, the general enervation which gradually takes possession of all the physical functions diminishes the animal warmth: this must be replaced from without, and nothing is therefore more agreeable to the operative than to have all the doors and windows closed, and to stay in his warm factory-air. Then comes the sudden change of temperature on going out into the cold and wet or frosty atmosphere, without the means of protection from the rain, or of changing wet clothing for dry, a circumstance which perpetually produces colds. And when one reflects that, with all this, not one single muscle of the body is really exercised, really called into activity, except perhaps those of the legs; that nothing whatsoever counteracts the enervating, relaxing tendency of all these conditions; that every influence is wanting which might give the muscles strength, the fibres elasticity and consistency; that from youth up, the operative is deprived of all fresh air recreation. . . .

That the growth of young operatives is stunted, by their work, hundreds of statements testify; among others, Cowell gives the weight of 46 youths of 17 years of age, from one Sunday school, of whom 26 [who were] employed in the mills, averaged 104.5 pounds, and 20 not employed in mills, 117.7 pounds. One of the largest manufacturers of Manchester . . . said on one occasion that if things went on as at present, the operatives of Lancashire would soon be a race of pigmies. A recruiting officer testified that operatives were little adapted for military service, looked thin and nervous, and were frequently rejected by the surgeons as unfit. In Manchester he could hardly get men of five feet eight inches; they were usually only five feet six to seven, whereas in the agricultural districts, most of the recruits were five feet eight.

The men wear out very early in consequence of the conditions under which they live and work. Most of them are unfit for work at forty years, a few hold out to forty-five, almost none to fifty years of age. This is caused not only by the general enfeeblement of the frame, but also very often by a failure of sight, which is a result of mule-spinning, in which the operative is obliged to fix his gaze upon a long row of fine parallel threads, and so greatly to strain the sight. . . .

In Manchester, this premature old age among the operatives is so universal that almost every man of forty would be taken for ten to fifteen years older, while the prosperous classes, men as well as women, preserve their appearance exceedingly well if they do not drink too heavily.

The influence of factory work upon the female physique also is marked and peculiar. The deformities entailed by long hours of work are much more serious among women. Protracted work frequently causes deformities of the pelvis, partly in the shape of abnormal position and development of the hip bones, partly of malformation of the lower portion of the spinal column. . . . That factory operatives undergo more difficult confinement than other women is testified to by several midwives and accoucheurs, and also that they are more liable to miscarriage. Moreover, they suffer from the general enfeeblement common to all operatives, and, when pregnant, continue to work in the factory up to the hour of delivery, because otherwise they lose their wages and are made to fear that they may be replaced if they stop away too soon. It frequently happens that women are at work one evening and delivered the next morning, and the case is none too rare of their being delivered in the factory among the machinery. . . .

But besides all this, there are some branches of factory work which have an especially injurious effect. In many rooms of the cotton and flax-spinning mills, the air is filled with fibrous dust, which produces chest affections, especially among workers in the carding and combing rooms. Some constitutions can bear it, some cannot; but the operative has no choice. He must take the room in which he finds work, whether his chest is sound or not. The most common effects of this breathing of dust are blood-spitting, hard, noisy breathing, pains in the chest, coughs, sleeplessness—in short, all the symptoms of asthma, ending in the worst cases of consumption. . . . But apart from all these diseases and malformations, the limbs of the operatives suffer in still another way. Work among the machines gives rise to multitudes of accidents of more or less serious nature, which have for the operative the secondary effect of unfitting him for his work more or less completely. The most common accident is the crushing of a single joint of a finger, somewhat less common the loss of the whole finger, half or a whole hand, an arm, etc., in the machinery. . . . Besides the deformed persons, a great number of maimed ones may be seen going about in Manchester; this one has lost an arm or a part of one, that one a foot, the third half a leg; it is like living in the midst of an army just returned from a campaign. But the most dangerous portion of the machinery is the strapping which conveys motive power from the shaft to the separate machines. . . . Whoever is seized by the strap is carried up with lightning speed, thrown against the ceiling above and floor below with such force that there is rarely a whole bone left in the body, and death follows instantly. . . .

A pretty list of diseases engendered purely by the hateful greed of the manufacturers! Women made unfit for childbearing, children deformed, men enfeebled, limbs crushed, whole generations wrecked, afflicted with disease and infirmity, purely to fill the purses of the bourgeoisie. And when one reads of the barbarism of single cases, how children are seized naked in bed by the overlookers, and driven with blows and kicks to the factory, their clothing over their arms, how their sleepiness is driven off with blows, how they fall asleep over their work nevertheless, how one poor child sprang up, still asleep, at the call of the overlooker, and mechanically went through the operations of its work after its machine was stopped; when one reads how children, too tired to go home, hid in the wool of the drying-room to sleep there, and could only be driven out of the factory with straps; how many hundreds came home so tired every night, that they could eat no supper for weariness and want of appetite, that their parents found them kneeling by the bedside, where they had fallen asleep during their prayers; when one reads all this and a hundred other villainies and infamies . . . how can one be otherwise than filled with wrath and resentment against a class which boasts of philanthropy and self-sacrifice, while its object is to fill its purse a tout prix?

Figure 1.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

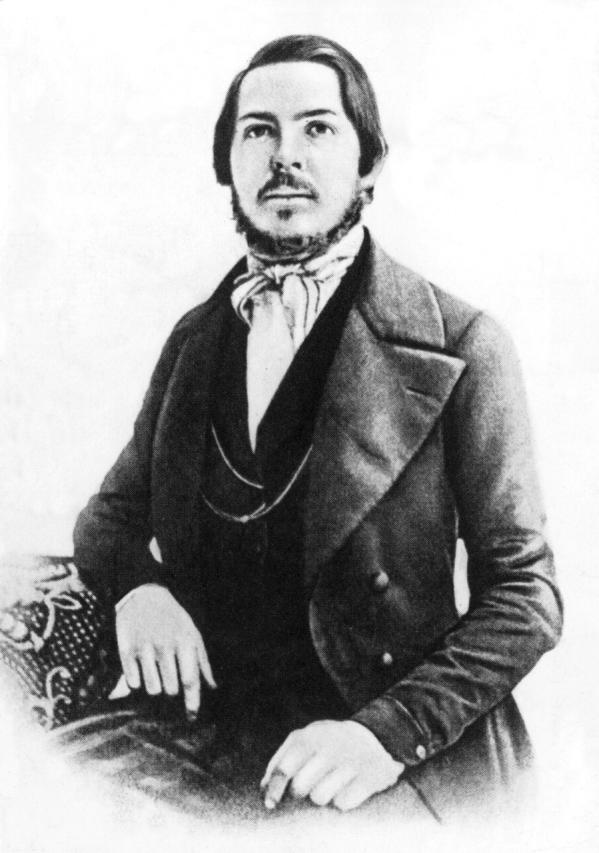

Opposite: German socialist philosopher Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) at the age of 25 in 1845. Photographer unknown.

Friedrich Engels. Excerpted from Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England. First published, Germany, 1845. English translation first published in 1886; republished with some revisions, and edited by Victor Kiernan. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1987:171–184.