Abstract

In this article, I trace the history of Chicago’s Health Department, exploring when and how housing conditions came to be considered a serious social problem requiring municipal regulation. Although journalists and labor leaders were among the first Chicagoans to link tenement housing to the spread of contagious disease, Health Department officials quickly began regulating the city’s housing stock under their own authority. I argue that in attempting to eliminate the dangers of contagious disease, a long-standing public health threat, health officials drew new attention to the dangers of multifamily dwellings and set a precedent for government regulation of living conditions in tenement dwellings.

IN 1876, JUST WEEKS AFTER being appointed commissioner of Chicago’s newly established Department of Health, Oscar Coleman De Wolf announced several new policies to fight disease in the city. First, he called for sanitary inspectors to inspect meat at the slaughterhouses and confiscate any that was tainted. Chicago’s food processors, particularly those connected with the expanding and increasingly hazardous animal-slaughtering and meat-packing industries, proved powerful opponents. Over the following 4 years, De Wolf battled the packers in the courts and fought their representatives in the City Council, finally winning passage of a fairly weak and largely unenforceable law requiring meat inspections.1

Few complaints were heard, however, about De Wolf’s other initiative: regular inspections of the city’s tenements. As thousands of European immigrants flowed into the city seeking jobs in rapidly expanding manufacturing enterprises and packing houses, tenement inspections became the city’s leading tool for protecting public health. Throughout the 1880s, health inspectors entered and examined the homes of the immigrant poor and working classes, establishing a government presence in ordinary people’s lives.

Reactions to De Wolf’s initiatives reveal much about power relations and politics in an industrializing city and help to shed new light on the strategies of the nascent public health movement. An aggressive and ultimately unsuccessful effort to limit the spread of disease, De Wolf’s tenement inspection program was initiated during a period of laissez-faire capitalism, amidst increasingly hostile conflicts between labor and capital over working conditions in the city’s factories. Long before local, state, and federal governments asserted their authority to regulate wages, hours, working conditions, or the dumping of slaughterhouse waste in the city’s waterways, the Chicago Department of Health secured legislation and public approval for regulating the rental dwellings of the urban poor. In a city where government regulations of property rights were minimal at best, De Wolf effectively redefined property rights in housing and removed the “tenement problem” from other issues of conflict between workers and their employers. Shifting from scientific to social to moral explanations for the presence of disease in the city, De Wolf designated tenements a health problem open to government regulation. Tenement inspections provided the new field of public health with the stamp of legal authority.

Epidemic disease was a serious and widely feared problem in 19th- and early 20th-century cities. De Wolf could confidently assert a public interest in regulating both tenements and tainted meat. Tenements, which De Wolf defined as any building in which 3 or more families resided in separate households, typically lacked indoor plumbing and often housed several families in a few tiny rooms. During the 1880s, growing numbers of immigrant wage laborers crowded into the 2- and 3-story wood frame or brick buildings that lined dusty, unpaved streets within walking distance of the factories west of the Chicago River and surrounding the slaughterhouses just south of the city limits. Living conditions in many of the city’s tenements did endanger the health of residents. Diphtheria, typhoid, cholera, smallpox, and yellow fever regularly appeared in working-class neighborhoods.2 But as sanitary reformers battled employers, such as those in the meat-packing business, urban housing—and tenements in particular—emerged as a central arena for legitimizing the public health movement.3

THE RISE OF SANITARY REFORM

De Wolf was in most ways typical of the physicians who joined the late-19th-century sanitation movement. He was born in 1835 and raised in western Massachusetts, where his father, Thaddeus K. De Wolf, practiced medicine for 62 years and participated in a local temperance movement. Oscar De Wolf studied with his father and then, beginning in 1856, attended a 2-year course at the Berkshire Medical College in Pittsfield, Mass, before heading to New York and later to France for further study. When the Civil War began, De Wolf returned to the United States and was appointed assistant surgeon of the First Massachusetts Cavalry; he later became surgeon for the Second Massachusetts Cavalry.4

De Wolf’s training in New York City and in France may have brought him in contact with many of the ideas that would influence the emerging field of public health. His service during the Civil War, however, probably crystallized those ideas into a more practical form. For many of the physicians who served in the Union Army, wartime experience significantly altered their views of their profession and of medicine’s relationship to government.

The war was the nation’s largest and most devastating medical event of the 19th century. Outbreaks of disease in military camps permanently changed the medical profession’s conception of the causality of disease. Many physicians, who watched as thousands of recruits died from diseases associated with poor sanitation in army camps, left the service with a new appreciation for sanitation and hygiene. Their experiences during the war seemed to demonstrate that disease could strike even the best of men; disease was not a moral but a “sanitary” problem. The war sparked unprecedented involvement in medical matters by government. The work of the United States Sanitary Commission, which was established during the war, demonstrated that government could play a significant role in preserving the health of recruits.5

By the 1880s, physicians, horrified by wartime experiences and influenced by new theories about disease causality emerging from Europe, were launching health reform efforts in several American cities. In 1866, New York City established the nation’s first municipal health department, which became a model for health departments in cities across the country. On the heels of the mid-1860s cholera epidemic and under pressure from a growing number of citizens’ sanitary associations, cities like Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and St Louis, along with the state of Massachusetts, established boards of health. Although sanitary reformers continued to push for health regulations, many urban health boards were active during periods of disease outbreaks but languished for lack of funding and lack of clear legal authority through much of the 1870s and 1880s.

The Massachusetts Board of Health, possibly the most effective in the country in the 1870s, regulated slaughterhouses and launched a series of investigations into tenement conditions. Chicago also established a municipal health board in the 1860s, under the leadership of John Rauch, who in the days and weeks following the fire of 1871 organized health services and worked to provide clean water, food, and housing for the 112 000 people left homeless by the fire.6 When the city’s leaders turned their attention toward rebuilding Chicago’s commercial center, however, the Board of Health was largely overlooked until 1876, when De Wolf was appointed to run the reorganized Department of Health.7

De Wolf was 42 when he was appointed Chicago’s health commissioner. In his nearly 13 years in office, he established a national reputation as a leader in the public health movement. In 1882, the British Association for the Advancement of Science made De Wolf an honorary member. A year later, he received the diploma of the Society of Hygiene of France. On his death in 1910, the Journal of the American Medical Association remarked that De Wolf “had achieved national prominence in sanitary matters.”8

Like health department officials in New York, De Wolf used his position to create a professionalized bureaucracy to supervise Chicago’s health. De Wolf transformed the Department of Health from a small semiofficial entity into a firmly established agency within the city’s government. In 1889, the Chicago Inter-Ocean wrote of De Wolf, “When he took charge of the office it could hardly be called a department of health. It had neither form nor comeliness and was doing nothing in the way of sanitary work except keeping a registry of the deaths.” The newspaper added, “The department has since developed into the most active and efficient health service in the United States.” Under De Wolf’s command, the department’s staff increased from 1 physician, an assistant commissioner, 2 secretaries, 2 meat inspectors, and 13 untrained sanitary inspectors to nearly 50 inspectors and physicians in 1889. In 1877, the department’s budget stood at $36 640, excluding amounts designated for scavenger service and dead animal removal, representing a little less than 9 cents per capita for general health work.9 By 1885, the department received a total appropriation of $240 460, including $171 383 for scavenger work and removing dead animals. Since the city’s population had grown rapidly, hitting 664 000 in 1885, the department’s per capita expenditure for healthrelated work increased to just over 10 cents per person. By then the Department of Health had the second largest budget in city government.10

De Wolf’s aim was not merely to establish the newly specialized field of public health but also to create areas of specialization within the field. Possibly using New York’s Health Department as his model, he divided his staff among various specialty areas. There were medical inspectors, sanitary policemen, meat inspectors, and tenement and factory inspectors, as well as a physician managing a smallpox hospital on the city’s west side. Each unit of inspectors was supervised by a manager who worked directly under De Wolf, and each was expected to produce a yearly report of its activities.11

De Wolf’s methods for preventing the spread of contagious disease represented a transitional period in medical science and in the field of public health. In the 1880s, a new field of medicine, bacteriology, emerged from the discovery of the cholera vibrio by a German physician, Robert Koch. Similar, independent experiments by Louis Pasteur in Paris had demonstrated decisively that disease was caused by microorganisms, not dirt. Several Chicago researchers were among the first in the United States to publicize the new germ theory of disease. Courses on germ theory were introduced into the city’s medical school curricula in the mid-1880s.12

De Wolf, apparently ambivalent about rejecting the older views, gradually introduced germ theory to public health work. While he continued to promote sanitary measures, such as the expansion of the city’s sewer system and regular cleaning of privy vaults, his agency helped shift the focus of public health practice from a primary concern with the cleanliness of the urban environment to the diagnosis and prevention of specific diseases. By 1888, De Wolf had declared that diphtheria was “not a filth disease, but an infectious disease, like smallpox.” By then he had already published a paper on Asiatic cholera in which he mentioned Pasteur and asserted that the disease was caused by bacteria. In the essay, published in 1885, De Wolf wrote, “It is not probable that the cholera poison is wafted about in the atmosphere except in a very limited extent.”13

The gradual incorporation of bacteriology into public health measures initially prompted renewed efforts to identify disease and prevent its spread. De Wolf established new and more rigorous requirements for reporting all varieties of disease. His yearly reports to the City Council included an array of statistics covering all causes of death and all outbreaks of disease, carefully listed by each sufferer’s age, nationality, and residential district.14

TENEMENT INSPECTIONS AS PUBLIC HEALTH PRACTICE

Most importantly, De Wolf launched a program of tenement inspections, the first in the city’s history, sending Health Department inspectors to examine “interiors” of tenements. In 1877, health inspectors examined 200 tenement buildings, finding just 4 “which could possibly be rated as fairly perfect, i.e. they did not violate any of the sanitary laws in force at that date [italics in original].” That year, inspectors examined rented dwellings only, but the program was expanded the following year to include “all classes of habitable buildings, upon a written request from the owner, agent, or occupant of such buildings.” De Wolf also sought to send inspectors into multifamily rental buildings without a request, or even permission, from the property owner. As a history of the department’s work published in the 1886 Health Department Report recounted, that move prompted some opposition; at least one City Council member derided De Wolf’s efforts and claimed that the health commissioner was driven by “fanaticism.”15

De Wolf’s programs, marking the initial steps of the urban sanitary movement, illustrate the tangled history of municipal governance and public health.16 He established tenement and factory inspections before gaining explicit legal authority to regulate housing and working conditions. When packing house owners launched a full-blown assault on his meat inspection program, De Wolf wrote a letter to the Chicago Tribune, commenting that “While I fully appreciate the necessity of additional laws, I must add that it is in my judgment absolutely impossible for the public officers in this country to contend successfully with great financial interests unless sustained by active organizations of good and patriotic citizens.”17 That support would not appear for another 25 years.

Tenement inspections, however, proved a less controversial approach. To demonstrate the need for full inspections of tenements, De Wolf, in 1879, appointed a voluntary corps of 30 physicians to survey all tenement dwellings in the city. With that report in hand, he appeared before the City Council and urged it to pass a “tenement housing ordinance.” He noted that “Incessant, systematic and searching inspection from house to house and street by street, from January to January, can alone prevent the growth of sanitary evils, which when matured and in full force, are beyond the control of men.”18 By then his program of tenement inspections had gained support from nearly all quarters of the city. The Citizens Association, a civic reform organization led by Marshall Field and George Pullman, 2 of the city’s leading businessmen, campaigned for tenement inspections, as did the Progressive Age, the city’s leading labor newspaper, and the city’s voice for the Republican Party, the Chicago Tribune.19

Still, builders and landlords objected when the City Council approved the city’s first housing ordinance in 1880. The law granted the Health Department the right to inspect and regulate sanitary conditions in places of employment and in tenement dwellings. It required property owners to remove all stench-causing refuse and to provide tenement residents with containers for garbage. Builders and landlords, complaining of the additional costs, challenged the city government’s right to regulate private property. Claiming that a man “should have complete jurisdiction” over his property, landlords urged the City Council to repeal the ordinance.20

With landlords refusing to comply with the municipal ordinance, the Illinois General Assembly, under pressure from sanitary reformers, labor, and business leaders, passed the state’s first Tenement and Factory Ordinance on May 30, 1881. The law put the sanitation and construction of all tenements, workshops, and lodging houses under the supervision of the Chicago Department of Health. Building owners quickly responded to the legislation by placing new clauses in rental contracts, stating that the tenant accepted the residence in its existing condition. According to most leases, the tenant was responsible for maintaining the dwelling to conform to the law.21

De Wolf sent inspectors throughout the city’s wage-laboring neighborhoods, citing tenants for violations of the law and sometimes forcibly removing them from their homes. As De Wolf noted in a speech before the state medical society, sanitary inspections represented the “police authority” in tenement districts. The “incessant and systematic searching” for disease was performed by former policemen who personified the department’s authority in the streets and dwellings of the city’s laboring classes. Sanitary inspectors were granted the same “powers” as “regular police,” with an additional power: “the power to enter any house without a search warrant between the hours of sunrise and sunset.” Moreover, the sanitary police were authorized to forcibly remove those suffering from smallpox to the city’s smallpox hospital.22

By 1887, the department’s tenement inspections had the full support of the law. Inspections were widespread and, in De Wolf’s view, “thorough.” In that year, health inspectors examined 31 171 occupied dwellings. Of these, 7702 were rented single-family dwellings with the inspections made at the request of the owner or occupant.23 An additional 2557 buildings under construction were examined, with inspectors typically making 2 or 3 visits to construction sites. Inspections involved examinations of “heating, lighting, ventilating, plumbing and drainage arrangements therein.” In 1887, inspectors issued 13 855 citations, some for multiple offenses in a single dwelling. Remedies for these violations included “defective plumbing repaired,” the construction of new sewers and drains, “ventilation applied to waste and soil pipes,” the cleaning of privy vaults, “rooms lime-washed, leaky roofs repaired, uninhabitable basements cleared of inhabitants, filthy yards cleaned,” and the cleaning of unoccupied grounds. In 1887, the Health Department filed 251 “suits against persons neglecting or refusing to provide the improvements demanded under the law.” The courts, according to the department’s report, ruled on the side of the Health Department in every case but two. In the few cases brought to the appeals courts, the lower courts’ rulings in favor of the Health Department were sustained.24

THE BURDENS OF HEALTH REGULATIONS

Although the state law seemed to place responsibility for conforming to Health Department regulations on property owners, landlords quickly shifted the costs onto tenants. With regulations issued in the 1880s, the Health Department sought to establish minimal standards for health and safety in new construction, putting the burden of compliance on the building owners.25 In existing buildings, however, department inspectors could do little more than cite tenants for violations of the Health Department codes. When the law specified that landlords bear the costs of sanitary ordinances, property owners often shifted the financial burden onto tenants. When property owners whose buildings were on streets with sewers were required to connect the buildings to the sewers, for example, they typically made the connections and then, when the lease was up, raised rents to cover the additional capital costs of sewer hookups and indoor plumbing. Indoor plumbing did enhance health and property values, but often at an additional cost to the tenants.

Some landlords simply forced tenants to pay all assessed fees on the rented homes. Walter L. Newberry, who owned scores of residential properties around the city and rented to skilled craftsmen and middle-class families, added new clauses to lease agreements in 1881, requiring tenants to pay property taxes, water taxes, and sewer connection fees. If the buildings were located on streets lacking sewers, Newberry’s leases stated that tenants must keep “outhouses, and washbasins in sanitary condition in accordance” with city ordinances. Newberry further protected himself with a clause stating that a Board of Health citation “shall be, among other things, conclusive evidence [among] the parties hereto of the breach of this covenant.” With rents running as high as $25 per month, Newberry’s properties were priced beyond the means of unskilled laborers.26

It is not clear how ordinary people responded to the arrival of sanitary inspectors in their homes. The city’s English-language newspapers, including the labor press, supported tenement inspections and apparently published no accounts of tenants refusing entrance to the inspectors. Still, the inspectors faced some resistance. Health Department reports from the 1880s generally include comments about the 2 or 3 households each year that refused entrance to the sanitary inspectors. In most cases, regular police were called, the homes were forcibly inspected, and sick residents were forcibly removed. Remarkably, this authority faced no legal challenges until 1922.25,27 Sanitary inspections likely incited some ethnic hostility among the city’s recent immigrants. The inspectors were predominantly Irish, charged with entering and inspecting the homes of recently arrived Polish, Greek, Italian, and Eastern European families.

De Wolf was aware of the potential for ethnic conflict between inspectors and tenement dwellers. Administrative control of the sanitary inspectors became a point of conflict—possibly the only conflict—between De Wolf and Mayor Carter Harrison. Harrison, whose immense charisma and masterly control over the distribution of patronage jobs yielded him 5 terms in office, personally hired all sanitary inspectors. Harrison was born in Kentucky and claimed to be a descendant of a signer of the Declaration of Independence. In a city that regularly voted Republican in national elections, Harrison, a Democrat, put together a diverse coalition to win election. He was, as Richard Schneirov notes, “a broker between most of the city’s organized interest groups,” including middle-class reformers, business moderates, German socialists, and Irish immigrants. But the mayor’s power was rooted in the city’s Irish neighborhoods. In the 1880s, the Irish were not the largest of the city’s immigrant groups, but they were among the most vocal and politically active, a powerful force in the Democratic Party since the 1850s. By 1865, one third of Chicago’s police were Irish, and in the 1880s, under the patronage of Mayor Harrison, the Irish gained an even greater proportion of the coveted jobs. Sanitary inspectors, hired from the police force, were predominantly Irish. Despite De Wolf’s repeated complaints that the system was tainted by politics, Harrison refused to relinquish control of even a slice of the city’s patronage jobs to the health commissioner.28

The inspection procedures illustrate the distinction drawn between the property rights of tenement dwellers and those enjoyed by people living in single-family dwellings. While health inspectors regularly entered tenement dwellings without warrants or court orders, they also made “special examinations” of dwellings occupied by single families, but only at the request of physicians, occupants, or owners. “This class of work was not at first intended to form a part of the ‘regular’ work of the inspectors,” De Wolf announced in 1882. But, he added, since “the public generally are recognizing the true value and benefit to health of perfect house sanitation” the department was willing to inspect single-family dwellings and “suggest proper remedies for all defects found.” In most cases, these inspections were made “as a last resort” by the occupant seeking relief from odors or poor construction.29

No single area of the city was targeted for inspections, but the single-family homes of the city’s elite were excluded. The department’s report for 1885 noted that inspections covered every area of the city, “except those classed as strictly ‘residence’ streets of the most expensive and thoroughly improved character.” Because Health Department inspectors entered single-family houses only at the request of the occupant or owner, neighborhoods with large numbers of multifamily rented dwellings were more likely to be inspected than areas lined with single-family, owner-occupied dwellings. As the department’s report for 1885 commented, “The method adopted was to apply the entire working force of inspectors to the most insanitary localities first, following this with the next most urgent localities, and so on to the end of the work. . . .”30

EXPLAINING THE “TENEMENT PROBLEM”

De Wolf’s reports to the City Council illustrate his analysis of the link between tenement dwellings and public health. He attributed the most intractable tenement conditions to immigrant families. His descriptions of tenement dwellings provided an elaborate social map of the city’s residents and reinforced categories separating social groups. In De Wolf’s view, the national origin of the occupants determined the sanitary conditions of tenement dwellings. Native-born Americans lived in “well-furnished” flats; Germans occupied tenements that were “comfortably built, but having less of the so-called modern conveniences.” De Wolf blamed the inferior quality of the tenements occupied by Italian, Polish, and Bohemian immigrants on a mix of custom and biology. He wrote, “There are a great many old buildings in this city which are unfit for habitation by civilized people, yet they are inhabited, and generally by Italians, Poles, Bohemians, and others, who, in their trans-Atlantic homes have been accustomed to live in crowded quarters.” De Wolf added that it was difficult to enforce tenement ordinances “against such habitual and hereditary unsanitary modes of living.” Since these immigrants rarely understood Health Department regulations, they required “constant watching” by sanitary inspectors.”31

But De Wolf did not believe that the residents’ nationality was the sole source of the tenement problem and the consequent spread of disease in the city. He also highlighted the residents’ status as low-wage workers. Here, he treated the city’s working classes as a singular group, never noting that native-born and German workers tended to congregate in higher-skilled and better-paying jobs, thus enabling them to afford more comfortable housing. While nationality might determine living conditions, it did not, in De Wolf’s view, correspond to differing levels of wages or employment opportunities. De Wolf contended that a growing class of permanent wage workers unable to purchase or rent a single-family dwelling rendered tenement housing inevitable. Without “proper” housing, wage workers would, in De Wolf’s view, remain the source of the city’s health problems. De Wolf’s views proved an exaggeration; nearly one fourth of the city’s wage laborers, most of whom were immigrants, owned some real estate in 1880. Still, De Wolf wrote that “the whole number of occupants of tenement houses is about equal to the foreign population, not because of their nationality, but because it is wage workers of all nationalities who are compelled to occupy tenement houses.”32

The city’s labor leaders agreed with this explanation—De Wolf’s second—for the city’s “tenement problem.” But labor leaders took the argument a step further. Since the 1870s, labor leaders had asserted that higher wages would help workers improve their housing conditions. Housing, and in particular a workers’ ability to set aside some money toward the purchase of a house, was part of what organized labor termed “an American standard of life,” and central to labor’s larger agenda. In a July 1881 call for a citywide strike, the Progressive Age conflated the “evils” of employers with those of landlords, urging workers to strike “against the growing spoilations [sic] through rents, profits, commissions, pools, speculations and peculations of the miscalled middle classes. . . .”33 To the city’s labor press, wages and working and housing conditions were intimately entwined.

De Wolf was well aware of the rumblings from the city’s nascent labor movement. By the early 1880s, Chicago had become the headquarters of the nation’s socialist and anarchist movements and a center of strength for the more moderate Knights of Labor. Even as De Wolf’s inspectors were roaming the tenement districts, unions associated with the Trades and Labor Assembly were holding regular meetings on the city’s south and west sides. More significantly, some of the city’s labor activists worked with the sanitary reform movement, seeking to use health regulations to improve living and working conditions for the city’s working classes. Mayor Harrison had looked to the Health Department to reconcile his diverse and often conflicting coalition of supporters. This coalition had forced the mayor to reorganize the city’s Health Department and to include at least one out-spoken socialist factory inspector, Joseph Gruenhut. A Bohemian-born labor activist and columnist in the Progressive Age, Gruenhut regularly attacked both employers and landlords, arguing that higher wages and home ownership opportunities were the keys to improving wage laborers’ living conditions and public health. For Gruenhut, an American “standard of life” included “better homes, less burdensome toile, and more agreeable conditions of labor,” along with higher wages.34

Although the Health Department was not empowered to legislate wage levels for the city’s laborers, a perceived link between housing conditions and wages appeared in the department’s yearly reports. The reports featured lengthy tables listing the wages and hours for most of the city’s trades and commercial workers. Summarizing the information, chief tenement and factory inspector W. H. Genund commented in his 1886 report that workers appeared to be achieving their long-standing goal of working shorter hours “without reducing the daily wages paid therefore.” He also noted that women earned 25% to 50% “less than the wages of men employed in the same trade or occupation,” and, without expressing an opinion on the disparity, added that “general superintendents draw annual salaries reaching far into the thousands of dollars.”35

Although Health Department reports implied that low wages and seasonal employment were linked to inadequate housing for wage laborers, De Wolf did not support labor’s demands for higher wages or shorter working hours. A vocal and often controversial advocate for tenement and factory inspections, De Wolf, unlike some of his staff, distanced himself from labor’s demands for higher wages. Instead, he began to advocate for the construction of “model tenements,” a solution first proposed in London and later promoted in New York in the 1840s. The “unpleasant fact,” De Wolf wrote, was “that practically no provisions are being made to house the toiling multitude of wage-workers in our city.” Those willing to construct rental housing for wage workers would not be expected to forgo a profit. Pointing to the success of the community of Pullman, built by George Pullman just south of the city, De Wolf argued that the construction of “blocks of tenement houses on the most approved plans for the wage working poor” could prove “highly profitable.”36 De Wolf, of course, could hardly foresee the violent conflict that would erupt in Pullman a decade later.

Working with volunteers from the Citizens Association, the Health Department in 1884 conducted a 9-month survey of all tenement dwellings. The association’s Committee on Tenement Housing was more direct than the Health Department’s assertions. Remarking on recent conflicts between labor and capital, the committee’s report argued that the construction of model tenements would “be a long stride in the direction of a general movement to bring capital and labor into closer economic union.”37 No one came forward to test this thesis by building model tenements. With this strategy, however, De Wolf and the Citizens Association effectively divorced the tenement problem from what many in the late 19th century called the “labor problem”: the growing demands of wage workers for higher wages and control over working conditions.

Despite his success in establishing tenement inspections in law and bureaucratic practice, De Wolf failed in another arena that was arguably equally threatening to the public health. His efforts to prohibit the sale of adulterated meat and to bar the packing houses from dumping animal waste in the Chicago River prompted widespread resistance from the city’s packers. That resistance campaign, combined with the election of DeWitt C. Cregier, a Democratic rival of Harrison, resulted in the new mayor firing De Wolf in 1889.38

HEALTH DEPARTMENT’S RETREAT FROM REGULATION

Tenement inspections continued after De Wolf’s departure. In the 1890s, however, the sanitary reform movement began to crumble and party politicians, rather than health reformers, ran the department. As one settlement house worker commented, health inspectors, loath to anger “friends of the neighborhood politicians,” refused to condemn “unsanitary tenements.”39 By 1894, the department’s chief inspector for the Bureau of Sanitary Inspection, Andrew Young, took just 6 pages in a 268-page report to discuss sewage, drainage, light, and air in the city’s homes. Much of the rest of the report featured graphs of morbidity and mortality rates for the city’s residents, reports on efforts to improve the quality of milk and meat sold in the city, and reports on conditions in the city’s factories. Despite growing acceptance of the germ theory of disease, Young offered a complex, and slightly convoluted, explanation of the cause of disease, reviving the old formula of linking immorality with poor health. “The fact is clear to us that crime is begotten by sin, and sin begotten by disease, disease begotten by filth and filth begotten by ignorance and neglect of the individual or the inefficiency of the agencies employed by the municipality to correct such conditions.” Yet in his view, the municipality and its Health Department were hardly inefficient. “So beneficial have been their [health inspectors’] operation that to-day the bath and toilet rooms of our hotels and residences are the altars of cleanliness, luxurious in their appointments, tasteful in every detail and construction.”40

While some settlement house workers asserted that low wages and irregular employment were directly linked to the inadequate shelter and poor health of many urban workers, Young glossed over possible causes for the city’s death rate. He instead asserted that “Health is wealth. Sickness in a community breeds demoralization, vice and crime, and adds to the burdens borne by the citizen and the community at large.” Housing reformers, who launched a 9-month study of tenement conditions 5 years later, were surprised to learn that the “bath and toilet” rooms in the homes of large numbers of impoverished Chicagoans were either nonexistent or in dangerously defective condition.41

Even in the 1880s, close inspections of tenement districts and surveillance of tenement residents had hardly abated the problem of disease. There were no major epidemics under De Wolf’s watch, but mortality rates from disease remained fairly steady. However, a precedent had been set. When settlement house workers took up the cause of public health and tenement reform in the 1890s, they effectively used the tenement and factory legislation to pressure the City Council to enforce sanitary regulations. They also pushed for the passage of new and stricter housing legislation.

But De Wolf’s tenement inspections had other, possibly unintended consequences. As De Wolf expanded the reach of the Health Department and its inspectors, property rights in the family home increasingly were conceived as rights that adhered only to owner-occupied, single-family dwellings. Under legislation passed in 1880 and 1881, tenement dwellings were placed in a legal category that included factories and workshops and excluded single-family houses.42 Tenement dwellings were open to inspection and regulation in ways that owner-occupied or rented single-family houses were not. Landlords’ efforts to enhance their profits by forcing tenants to maintain their housing according to Health Department regulations further strained the budgets of tenement residents. Although De Wolf could confidently assert a public interest in ridding Chicago of disease, he ultimately placed the burden of health regulations on those least likely to challenge his authority, tenement residents.

At the same time, De Wolf maneuvered between scientific, social, and moral explanations for the tenement problem to establish the legitimacy of public health work and legal authority for his interventions in the homes of the urban poor. His strategic use of tenement inspections to bolster the authority of the Health Department helped to separate struggles for improved housing from conflicts between labor and capital. De Wolf designated housing a health problem, one that could be solved by government regulations or the commercial construction of model tenements.

De Wolf’s focus on the links between the national origins of residents and their living conditions obscured the economic issues at the heart of the “tenement problem.” While articulating a public interest in regulating tenements, De Wolf helped to shift the focus of the city’s housing and health reformers from Chicago’s evolving and complex class system to the realm of ethnic, and later racial, taxonomies. Certainly, concern with sanitation was part of a genuine effort to improve the health of the city’s residents. But De Wolf’s rhetorical blending of racial hierarchies and scientific analysis of the threat of disease emanating from tenements permitted propertied Chicagoans to avoid investing capital in improving tenement dwellings or raising wages so that laborers could afford better housing, and it provided them with pseudo-scientific justifications for regulating the immigrant poor.43

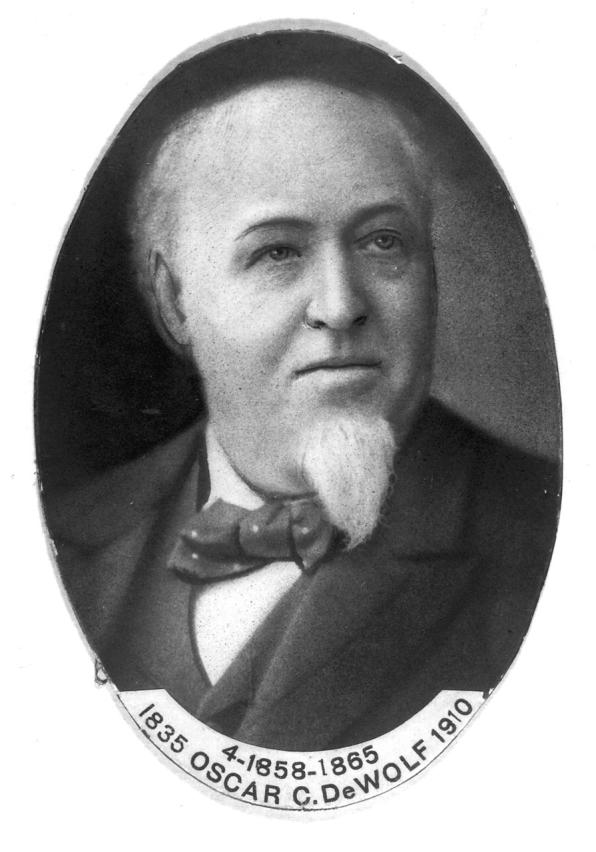

Figure 1.

Children playing in the streets near the stockyards, Chicago.

Figure 2.

Oscar C. De Wolfe (1835–1910).

Figure 3.

View from the rear of the Maxwell Street settlement, Chicago.

Figure 4.

Neighborhood scene with geese, Chicago.

Figure 5.

Woman mending by a window in a Chicago slum dwelling.

Peer Reviewed

Endnotes

- 1.Seizures of condemned meat did increase from 85 950 pounds in 1873 to 11 991 164 pounds in 1893, but the Chicago Tribune complained throughout the late 1870s and 1880s of inadequate inspections and issued regular reports of people sickened by tainted meat. See Bessie Louise Pierce, A History of Chicago, vol 3, The Rise of the Modern City, 1871–1893 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1957), 322; Chicago Tribune, October 22, 1879, 8; and Chicago Tribune, October 27, 1879, 4.

- 2.See Chicago Department of Health reports for the 1880s; Christine Meisner Rosen, The Limits of Power: Great Fires and the Process of City Growth in America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 173; E. Robinson, Robinson’s Atlas of the City of Chicago, Illinois (New York: Robinson, 1886); Pierce, Rise of the Modern City, 50–56; and Richard Sennett, Families Against the City: Middle Class Homes of Industrial Chicago, 1872–1890 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 25–39.

- 3.Much excellent scholarly work has been produced on the late 19th century’s sanitary reform movement. While earlier work celebrated the achievements of the sanitarians, some of the more recent work argues that sanitary reform work contained elements of social control. Historians looking at the history of social medicine and immigration highlight the nativist strain in sanitary reform; others spotlight the sanitarians’ utilitarian strategies to improve labor’s productivity by improving worker health. My aim is to highlight the significance of tenement inspections in sanitary work and to explore the ways public health efforts functioned to redefine property rights in housing. See, for example, John Duffy, The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992); Alan M. Kraut, Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the “Immigrant Menace” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994); Judith Walzer Leavitt, The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996); and Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz, Public Health and the State (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972).

- 4.The Pittsfield Republican, 1906; Dictionary of American Medical Biography, ed. Howard A. Kelly and Walter L. Burrage (Boston: Milford House, 1971), 324–325; Journal of American Medical Association 54 (1910): 1229; James C. Russell, History of Medicine and Surgery and Physicians and Surgeons of Chicago (Chicago: Biographical Publishing Corporation, 1922), 100.

- 5.James H. Cassedy, Medicine in America: A Short History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 64–65.

- 6.Bulletin of the Society of Medical History of Chicago (Chicago: The Society, 1911–1948), 89–104. Rauch was a former lieutenant colonel and surgeon in the Union Army and a founding member of the American Public Health Association.

- 7.Duffy, The Sanitarians, 120–124, 140–150; Rosenkrantz, Public Health and the State, 52–54; Chicago Council Proceedings, 1876–1877, 16, 111; Pierce, Rise of the Modern City, 320.

- 8.The Pittsfield Republican, 1906; Journal of the American Medical Association 54 (1910): 1229.

- 9.Isaac D. Rawlings, The Rise and Fall of Disease in Illinois (Springfield, Ill: Schepp & Barnes, Printers, 1927), 327; Chicago Inter-Ocean, July 23, 1889; Pierce, Rise of the Modern City, 320–323.

- 10.Report of the Department of Health for the City of Chicago for the Year 1885 (Chicago: George K. Hazlitt & Co, Printers, 1886), 122.

- 11.See Department of Health reports for 1876–1889.

- 12.Thomas Neville Bonner, Medicine in Chicago: 1850–1950, A Chapter in the Social and Scientific Development of a City (New York: Stratford Press Inc, 1957), 25–26; Erwin H. Ackerknecht, A Short History of Medicine, rev ed (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982), 177–178; Donald L. Miller, City of the Century (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 430; Cassedy, Medicine in America, 76–86.

- 13.Oscar C. DeWolf, Asiatic Cholera: A Sketch of Its History, Nature, and Preventive Management (Chicago: American Book Company, 1885), 9.

- 14.Cassedy, Medicine in America, 78; Reports of the Department of Health for the Years 1877–1889 (Chicago: George K. Hazlitt & Co, Printers, 1890).

- 15.Report of the Department of Health for the City of Chicago for the Year 1886 (Chicago: George K. Hazlitt & Co, Printers, 1887), 47–49.

- 16.Even before De Wolf’s appointment, the city comptroller, arguing that the health board had exceeded its legal authority in hiring sanitary inspectors, refused to pay the sanitary inspectors. When the board sued the city, the case was decided in its favor, but only after several years of battles among city officials over expenditures for healthrelated activities. The appellate courts ruled that the statute establishing the board had broad powers, including the hiring of sanitary inspectors. See “The People of the State of Ill. ex. rel. H.W. Jones,” in Reports of Cases at Law and in Chancery Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Illinois, vol 45, ed. Norman L. Freeman (Chicago: E. B. Myers and Company, 1869), 297–301. Similarly, De Wolf’s initial efforts to regulate the slaughtering industry were challenged in court, with the courts ruling that the commissioner did not have the legal authority to issue such regulations. See “Charles H. Tugman v. The City of Chicago,” in Reports of Cases of Law and Chancery (Springfield, 1876), 405–412.

- 17.Chicago Tribune, 22October1879, 8.

- 18.Report of the Department of Health of the City of Chicago for the Year 1879–80 (Chicago: George K. Hazlitt & Co, Printers, 1881), 22. Pierce, in Rise of the Modern City (p. 54), asserts, “Not until 1880 did a municipal ordinance give the Department of Health the right to inspect and regulate sanitary conditions even in places of employment.” But, according to the board’s yearly reports, sanitary inspectors were inspecting tenement housing as early as 1875.

- 19.The Progressive Age, October 1, 1881, 4, and March 5, 1881, 2; Chicago Daily Tribune, 20September1874.

- 20.Chicago City Council Proceedings, 1881 and 1882, 25. Quoted in Pierce, Rise of the Modern City, 54.

- 21.Walter L. Newberry Estate, Financial Records, Newberry Library Collection. Newberry owned scores of houses and multifamily dwellings, which he rented to skilled laborers.

- 22.Report of the Board of Health of the City of Chicago for the Years 1874 and 1875 (Chicago: Bulletin Printing Co, 1876), 91.

- 23.“Report of the Tenement and Factory Inspectors,” in Report of the Department of Health of the City of Chicago for the Year 1887 (Chicago: M. B. Kenny, Printer, 1888), 55–56.

- 24.Report of the Department of Health for the Years 1876–1877 (Chicago: Clark & Edwards, Printers, 1878), 70–73.

- 25.Construction regulations also generated opposition. De Wolf noted that many builders, resisting the Health Department’s regulations, seemed “to think that the law should leave them to construct buildings entirely of their own ideas.” As New York’s tenement reformer, Robert W. DeForest, would note 2 decades later, legislation designed to regulate construction on private property seemed to run counter to the most fundamental ideals of American liberty: “Most of us have been brought up to believe that, as owners of real estate, we could build on it what we pleased, build as high as we pleased, and sink our buildings as low as we pleased. Our ideas of what constitutes property rights and what constitutes liberty are largely conventional.” Report of the Department of Health for 1887, 6; The Tenement House Problem, Including the Report of the New York State Tenement House Commission of 1900, ed. Robert W. De Forest and Lawrence Veiller (New York: Macmillan Company, 1903), 84.

- 26.Walter L. Newberry Estate, Financial Records, Newberry Library Collection.

- 27.“The People ex rel Jennie Barmore, Relatrix, vs. John Dill Robertson et al Respondents,” in Reports of Cases at Law and in Chancery, vol 302 (Springfield, Ill: 1922), 422–436.

- 28.Richard Schneirov, Labor and Urban Politics: Class Conflict and the Origins of Modern Liberalism in Chicago, 1864–97 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 88–89; Miller, City of the Century, 441–449; Report of the Department of Health for the City of Chicago for the Years 1883/1884 (Chicago: George K. Hazlitt & Co, Printers, 1885).

- 29.Report of the Department of Health of the City of Chicago for the Year 1882 (Chicago: George K. Hazlitt & Co, Printers, 1883), 6.

- 30.Report of the Department of Health for 1885, 72.

- 31.Report of the Department of Health for 1882, 47–48.

- 32.Report of the Department of Health for 1882, 47.

- 33.The Progressive Age, July 23, 1881, and October 8, 1881.

- 34.Schneirov, Labor and Urban Politics, 89, 147–148.

- 35.Report of the Department of Health for 1886, 74–77.

- 36.Elizabeth Blackmar, Manhattan for Rent, 1785–1850 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989), 207–212; Report of the Department of Health for 1883/1884, 21–22. Pullman boasted that since the town was completed in 1881, not a single case of cholera, typhoid, or yellow fever had been reported. Miller, City of the Century, 225; The Rights of Labor, April 1893, np.

- 37.Robert Hunter, Report of the Committee on Tenement Houses of the Citizens Association of Chicago (Chicago: Geo. K. Hazlitt & Co, Printers, 1884), 7.

- 38.Chicago Tribune, April 19, 1889, and May 23, 1889; Pierce, Rise of the Modern City, 364–366. Cregier was elected with the support of organized labor, some socialists, and urban reformers. Gruenhut, the tenement inspector, had written much of the Democratic Party’s platform and kept his job with the Health Department after the election. It is not entirely clear why Cregier forced De Wolf out, but the Chicago Tribune, admittedly anti-Cregier, suggests that the new mayor distributed jobs to his labor supporters; Schneirov, Labor and Urban Politics, 280–283.

- 39.Howard Eugene Wilson, “Mary E. McDowell and Her Work as Head Resident of the University of Chicago Settlement House, 1894–1904,” unpublished dissertation, University of Chicago, 1927, 36–37.

- 40.Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of Chicago for the Year Ended December 31, 1894 (Chicago, 1895), 183–189; Wilson, “Mary E. McDowell and Her Work,” 94–95.

- 41.Annual Report of the Department of Health for 1894, 188; Hunter, Report of the Committee on Tenement Houses, 3.

- 42.In 1884, the New York Court of Appeals had ruled that a law banning cigar making in a tenement dwelling violated the cigar makers’ rights to labor. The court’s decision, based on the freedom to contract for work, similarly placed the tenement in a legal category that linked it to production and separated it from the single-family home. See “In re Application of Paul” (no number in original), Court of Appeals of New York, 94 NY 496, 1884 (Lexis 293).

- 43.For a fuller discussion of the shift from class to ethnic and racial analysis of health problems, see, for example, Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress, ed. Sander Gilman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985); Gilman, Difference and Pathology: Stereotypes of Sexuality, Race and Madness (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985); and Nancy Stepan, “Race and Gender: The Role of Analogy in Science,” Isis 77 (June 1986): 261–277.