Abstract

In many ministries of health, applied epidemiology and training programs (AETPs) are responsible for detecting and responding to acute health events, including bioterrorism. In November 2001, we assessed the bioterrorism response capacity of 29 AETPs; 17 (59%) responded.

Fifteen countries (88%) had bioterrorism response plans; in 6 (40%), AETPs took the lead in preparation and in 6 (40%) they assisted. Between September 11 and November 29, 2001, 12 AETPs (71%) responded to a total of 3024 bioterrorism-related phone calls. Six programs (35%) responded to suspected bioterrorism events.

AETPs play an important role in bioterrorism surveillance and response. Support for this global network by various health agencies is beneficial for all developed and developing countries.

IN THE FALL OF 2001, ONE hundred thirty-six Epidemic Intelligence Service officers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were called on to play an important role in the investigations and interventions that followed the anthrax attack in the United States.1 The rapid response to this threat to public health led to appropriate antimicrobial prophylaxis to prevent additional cases of disease.2 At the same time, ministries of health worldwide were actively involved in gathering bioterrorism-related information to use in creating preparedness plans.3

In many countries, the preparation and response to bioterrorism and other acute public health problems are led by applied epidemiology and training programs (AETPs), which are part of, or closely affiliated with, host countries’ ministries of health. These agencies must be prepared to respond to outbreaks of disease, natural calamities, and bioterrorism. It is essential that they systematically develop and strengthen their surveillance, response, analysis, and prevention capacities.4

A robust public health infrastructure for surveillance and response is critical to safeguard populations from all acute health events—including bioterrorism.5 Given the ongoing threat of bioterrorism, ministries of health need to have the capacity to detect, diagnose, characterize epidemiologically, and respond effectively to any unusual health event.6 Public health capacity, based on current knowledge and a high state of alert, provides the best defense against intentional and unintentional health events.7

THE PROGRAMS

Typically, AETPs are 2-year training and service programs designed to build the capacity of applied epidemiology and public health practice in host countries, while providing such key services as surveys, outbreak investigations, and the strengthening of existing health programs (Table 1 ▶).8 The graduates of these programs have often quickly responded to and resolved outbreaks in their countries and regions. For example, trainees and graduates of the Uganda AETP investigated and helped contain a nationwide outbreak of ebola hemorrhagic fever in 2000 and 2001.8,9

TABLE 1—

Estimated Number of Graduates and Trainees of Applied Epidemiology and Training Programs, by World Health Organization (WHO) Region, 2001

| WHO Region | Year First Program Started | Population of Region as of Year 2000 (Millions) | Trainees to Date | Trainees per 100 Million Population | No. of Programs | No. of Programs That Respondeda (%) |

| Africa | 1993 | 616 | 223 | 36 | 4 | 3 (75) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 1989 | 485 | 99 | 20 | 3 | 3 (100) |

| Europe | 1992 | 872 | 141 | 16 | 5 | 2 (40) |

| PAHO (Americas)b | 1975b | 816 | 382b | 71b | 8c | 3 c,d (38) |

| EIS (US) | 1951 | 260 | 2647 | 1018 | ... | ... |

| Southeast Asia | 1980 | 1508 | 194 | 13 | 3 | 2 (67) |

| Western Pacific | 1984 | 1728 | 326 | 19 | 6 | 4 (67) |

| Total | 5965 | 1365b | 23b | 29 | 17 (59) |

Note. PAHO = Pan American Health Organization; EIS = Epidemic Intelligence Service.

Source. Adapted from White et al.8

aFor details on questionnaire, see “Methods” section.

bPAHO, excluding the EIS (US).

cPAHO, including the EIS (US).

dOf the 6 countries under the Central America Applied Epidemiology and Training Program, 1 responded.

Most AETPs are members of the Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Interventions Network (TEPHINET), which was established in June 1997 with the mission “to strengthen international public health capacity through initiating, and supporting, and networking of field-based training programs that enhance competencies in applied epidemiology and public health interventions.”10 This network is strengthened by support from various partners, including representatives of the training programs, the CDC, and the World Health Organization (WHO).8 Members share technical assistance for improving surveillance, disease prevention, and health promotion programs and collaborate with WHO-sponsored and other multinational outbreak response teams.8

In the sections below, we describe an assessment of the public health response capacity of the AETPs to determine how public health agencies can support their key preparation and response activities.

METHODS

In November 2001, we developed a tool to assess the needs of AETPs to develop greater capacity to respond to bioterrorism and other acute health events. All 29 members of TEPHINET were invited to respond to a self-administered questionnaire. Questionnaires were initially sent by e-mail to all TEPHINET members. Follow-up e-mails and fax messages were sent 1 to 2 weeks later to encourage participation.

The questionnaire asked for information about the following:

• AETP response to acute health events, and the type and number of bioterrorism-related communications after September 11, 2001.

• Investigation of any possible bioterrorism event since September 11

• Availability of national bioterrorism response plans

• Involvement of programs in preparation of the plan

• Contribution of TEPHINET, WHO, and CDC in dealing with bioterrorism issues

• Their needs and interests in improving their bioterrorism response capacity

Epi-Info 2000 (version 1.1.2) was used to perform descriptive analyses.11

RESULTS

AETPs cover approximately 45 countries through 29 individual programs, including 24 (83%) that serve a single country and 5 (17%) that serve more than one country. Seventeen of 29 AETPs (59%) responded from all 6 regions of the WHO; the Epidemic Intelligence Service program (US) did not respond (Table 1 ▶).

Twelve AETPs (71%) had responded to bioterrorism-related telephone calls from the public (median = 180, range = 12–965), the press (median = 16, range = 6–250), and a ministry of health (median = 9, range = 2–40). Fifteen of 17 respondents (88%) reported that at least one of their countries had bioterrorism plans in place; 6 of 15 respondents (40%) said they had taken the lead on drafting the bioterrorism plan for a ministry of health; 6 (40%) had contributed to, but not led, planning; and 3 (20%) were not involved.

Six respondents (35%) had investigated at least one possible bioterrorism event between September 11 and November 29, 2001. Twelve programs (71%) listed TEPHINET as a useful partner on bioterrorism issues, and 10 programs (59%) also listed the Division of International Health of the Epidemiology Program Office at the CDC and the WHO as contributors to their bioterrorism response. Fourteen of the programs (82%) reported that they would like assistance from the CDC, TEPHINET, and WHO in strengthening their emergency management and coordination of responses to acute health events. Nine (53%) requested help with planning workshops, 8 (47%) requested joint exercises, 8 (47%) requested training curricula, and 7 (41%) requested communications training.

DISCUSSION

In every country, a strong public health infrastructure for surveillance, early detection, and response to acute health events is also the primary means of protecting the public from bioterrorism.5,7 Many countries provide substantial political and financial support for defense, law enforcement agencies, international treaties, and diplomatic efforts to defend against bioterrorism.5,7 However, the recent anthrax outbreak in the United States illustrated that clinicians and public health systems are likely to be the detectors of and responders to bioterrorism events.5,7 The capacity of the public health system to respond quickly and appropriately is crucial at the national, regional, state, and local levels.12 Our findings confirm that AETPs were active in responding to such health threats in their host countries and regions.

Public health surveillance systems must be improved globally if they are to detect biological attack or newly emerging pathogens such as severe acute respiratory syndrome.6 A recent report of the US General Accounting Office identifies the AETPs of the TEPHINET network as core elements of the global surveillance and response system.4 TEPHINET’s role after the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center was to provide members with documents such as articles and recommendations from the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and reports on bioterrorism and Web site addresses, all of which were from the CDC and WHO. Such reference materials allowed busy national and international staff to concentrate on core public health activities instead of spending many hours each day responding to telephone inquiries.

Bioterrorism is unpredictable by nature. While large industrialized countries may be at higher risk, it is impossible to rule out the possibility of arbitrary acts of bioterrorism in even the smallest country. The entire international community is at risk for bioterrorism. Biological and chemical weapons programs are believed to be present in at least 17 countries.6,7 Following the first report of the intentional mailing of anthrax in the United States in 2001, within one month, European countries had handled more than 7000 mail threats and public health laboratories had investigated more than 4000 bioterrorism threat letters.13

This assessment was intended to provide information quickly. It has several limitations. The assessment tool was self-administered, which may have led to reporting bias. It was conducted in English, although for many AETPs, English is not generally used or understood. Only 17 of 29 AETPs (59%) responded, which may have led to underestimation or overestimation of the efforts directed at bioterrorism-related public health activities. Because there was no probability sampling, the results cannot be generalized to other countries.

CONCLUSIONS

This assessment is important to public health partners for several reasons. It suggests that responding AETPs are central to their countries’ preparedness for, surveillance of, and response to bioterrorism. Moreover, the key role of AETPs in public health surveillance places them in the first line of response to bioterrorism in their respective countries. To perform this vital role, many AETPs need technical assistance, financial assistance, or both to help develop their capacities to detect and respond to possible bioterrorism events in a timely manner. Finally, many partners have collaborated to build and sustain AETPs, including national governments, the CDC, TEPHINET, and the WHO. Continuing to strengthen and use this global network to detect and respond to bioterrorism is in the best interest of all developed and developing countries.

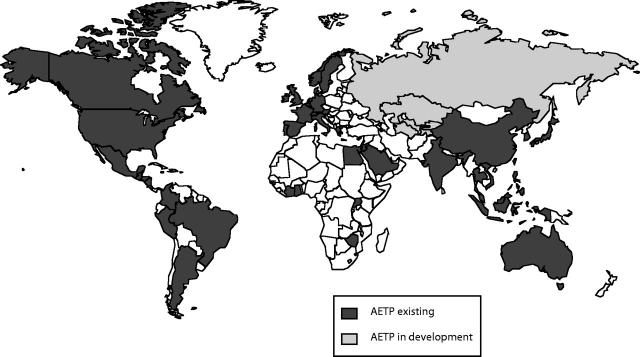

FIGURE 1—

Applied epidemiology and training programs (AETPs) worldwide, 2002.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the members of TEPHINET that provided data for this report.

Contributors All authors contributed to the concept and content of the report and participated in drafting and revising the report.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Press release: update: largest-ever deployment of CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service officers. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/pressrel/r020125.htm. Accessed October 20, 2002.

- 2.Jernigan DB, Raghunathan PL, Bell BP, et al. Investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax, United States, 2001: epidemiologic findings. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1019–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polyak CS, Macy JT, Irizarry-De La Cruz M, et al. Bioterrorism-related anthrax: international response by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1056– 1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Health: Challenges in Improving Infectious Disease Surveillance Systems. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office; August2001. Publication GAO/NSAID-01-722.

- 5.Garrett L. The collapse of global public health and why it matters for New York. Bull N Y Acad Med. 2001; 78:403–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhawan B, Desikan-Trivedi P, Chaudhry R, Narang P. Bioterrorism: a threat for which we are ill prepared. Natl Med J India. 2001;14:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ala’Aldeen D. Risk of deliberately induced anthrax outbreak. Lancet. 2001;358:1386–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White ME, McDonnell SM, Werker DH, Cardenas VM, Thacker SB. Partners in international applied epidemiology and training and service, 1975–2001. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of ebola hemorrhagic fever—Uganda, August 2000–January 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Interventions Network. Available at: http://tephinet.org/about.htm Accessed October 21, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Alperin M. Using Epi-Info 2000: A Step-by-Step Guide. Soquel, Calif: Toucan Ed; 2001.

- 12.Peterson LR, Ammon A, Hamouda A, et. al. Developing national epidemiological capacity to meet the challenges of emerging infections in Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:576–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coignard B. Bioterrorism preparedness and response in European public health institutes. Eurosurveillance. 2001;6:159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]