Abstract

Objectives. We identified race-associated differences in survival among HIV-positive US veterans to examine possible etiologies for these differences.

Methods. We used national administrative data to compare survival by race and used data from the Veterans Aging Cohort 3-Site Study (VACS 3) to compare patients’ health status, clinical management, and adherence to medication by race.

Results. Nationally, minority veterans had higher mortality rates than did white veterans with HIV. Minority veterans had poorer health than white veterans with HIV. No significant differences were found in clinical management or adherence.

Conclusions. HIV-positive minority veterans experience poorer survival than white veterans. This difference may derive from differences in comorbidities and in the severity of illness of HIV-related disease.

Racial disparities in processes of care and health outcomes are of growing concern in the United States. Despite improvement in overall health, disparities persist between minority and White patients in the burden of illness and death experienced.1 A major challenge for the reduction and eventual elimination of racial disparities is understanding their etiologies. Possible etiologies to consider include severity of the patient’s HIV and comorbid illness at first presentation for care, the clinical services received, and the patient’s level of participation in treatment.

Veterans receiving treatment for HIV infection represent a unique and scientifically important group for the study of racial disparities in health care. First, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System provides an opportunity to study racial disparities in health without having to control for health insurance status, because all veterans have essentially the same level of health insurance coverage.2 Second, comprehensive data on diagnoses and survival are available at the national level, which provides a dataset large enough to allow observation of racial disparities in survival and to allow measurement of their magnitude. Third, veterans in care are predominantly minority patients with lower-than-average incomes.3 As such, veterans with HIV represent an especially vulnerable population. Fourth, since the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), outcomes in those with HIV are highly dependent on the processes of care (access to HAART and prophylaxis for opportunistic infection).4 Finally, by use of in-depth clinical data available from the Veterans Aging Cohort 3-Site Study (VACS 3), it becomes possible to assess a patient’s baseline severity of HIV and comorbid illness and HIV-related medication use and adherence and to determine whether these variables also vary by race.

We used national VA administrative data to examine differences in survival by race in HIV-positive veterans. We then used in-depth clinical data from VACS 3 to explore explanations for racial disparities in survival. Potential etiologies examined included health status at study entry, use of clinic services, clinical management, and adherence to HIV-related medications.

METHODS

Nationally Identified HIV-Positive–Veteran Data

Use of national administrative data was approved by the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and University of Pittsburgh institutional review boards. We searched administrative inpatient and outpatient treatment files from all VA Healthcare Systems, using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes adapted from the methodology of Fasciano and colleagues,5 to identify HIV-positive veterans aged 25 to 84 years who received a first HIV diagnosis between June 1999 and September 2001. Our program searched for ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 042–044 (AIDS), 044.9 and V08 (asymptomatic HIV), and 795.8 (inconclusive test results), as well as for diagnosis-related group (DRG) codes 488–490. This procedure, which had demonstrated 93% sensitivity in identifying VACS 3 participants as HIV positive, yielded 7425 HIV-positive veterans.

Race data were obtained from the National Patient Care Database. Of the 7425 HIVpositive veterans, 1595 were of unknown race and 15 and 25 were American Indian and Asian, respectively. We included veterans categorized as White, Black, Hispanic White, and Hispanic Black. Hispanic White and Hispanic Black were combined into 1 Hispanic group.

We obtained mortality data (as of September 2002) from the beneficiary identification and records locator system and from administrative inpatient files. Mortality data from the VA have been shown to document 95% of all veteran deaths.6 We excluded 104 veterans who were first identified as HIV positive and died on the same day and 10 who had a death date before their last visit date. A total of 5676 patients were used in the analyses, including 634 deaths identified through a median follow-up period of 1.9 years.

We conducted sensitivity analyses on whether patients were identified as inpatients or outpatients, because only veterans being seen in outpatient clinics were eligible for enrollment in VACS 3. We report mortality rates for both analyses.

VACS 3

To gain more insight into racial disparities in health and survival, we analyzed data from VACS 3, a longitudinal study of HIV-positive veterans from infectious-disease clinics at 3 VA Medical Centers in Houston, Tex; Cleveland, Ohio; and Manhattan, NY. Eighty-five percent of HIV-positive patients seen in these clinics during the study period were enrolled in the study. Survey coordinators explained the study (purpose, who was being recruited, potential risks and benefits, and confidentiality) and requested consent for the survey, medical record review, and follow-up contact. VACS 3 is described in detail elsewhere.7,8

Baseline survey data were collected from patients and their providers between June 1999 and July 2000, and follow-up data were collected approximately 1 year after enrollment. Our analysis used survey data collected at baseline and electronic medical record data, which included diagnosis, laboratory, pharmacy, and death data.

Age and race data were available for all VACS 3 participants. Of the 881 participants, 879 were White, Black, or Hispanic, and 870 of them had complete CD4 count and viral load data. Five of them were excluded from analyses because their date of death was before their last visit date; 865 participants (98%) were included in analyses.

Patient Characteristics.

Patient’s race and gender were collected on the provider survey. Age was calculated with administratively collected date of birth and patient survey date. When race was missing from the provider survey, we used race as recorded in the National Patient Care Database from the VA electronic administrative data. Race was available from the provider survey for 92% of participants. We evaluated current smoking and homelessness from the patient survey, and exposure to HIV through intravenous drug use from the provider survey.

Health Status.

We evaluated health status at baseline with provider-reported probability that the patient would be alive in 5 years (physician prognosis), CD4 count per cubic millimeter (mm3), HIV-1 viral load copies per milliliter (mL), number of medical comorbidities, and number of HIV-related conditions. We asked the providers to estimate the probability that the patient will be alive in 5 years. This variable was strongly associated with survival in the VACS 3 data (C-statistic = .77; P = .001). We considered patients in the 90% to 100% survival category as having a high probability of being alive in 5 years.

CD4 count per mm3 and HIV-1 viral load copies per mL from laboratory data were also assessed. A viral load greater than 500 copies per mL is considered to be “detectable,” an unfavorable indicator, and a CD4 count less than 200 per cubic mm3 is considered to be low and indicative of declining health in HIV-positive patients.9

We identified 19 medical comorbidities and 13 HIV-related conditions. Information on medical comorbidities was obtained at baseline from the patient survey for symptoms of peripheral neuropathy and depression (according to the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) and from the provider survey for congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, pulmonary disease, and stroke. ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes from administrative patient treatment files were scanned to determine whether the patient had 1 or more inpatient or 2 or more outpatient diagnoses for non-HIV-related cancer, coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction, hypertension, pancreatitis, severe mental illness, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse in the past 5 years. We searched laboratory data to identify whether the patient had ever had anemia, hepatitis C, hyperlipidemia, transaminitis (presence of liver injury test abnormalities), or renal insufficiency before the baseline survey. Diabetes was defined with a combination of laboratory and pharmacy data.

Information on conditions related to HIV was obtained at baseline from the provider survey for HIV dementia; cytomegalovirus; and cryptococcus, coccidiomycosis, toxoplasmosis, or histoplasmosis. ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes from administrative patient treatment files were used to determine whether the patient had 1 or more inpatient or 2 or more outpatient codes for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), Kaposi’s sarcoma, tuberculosis, lymphoma, HIV wasting, bacterial pneumonia, candidiasis, herpes simplex or zoster, atypical Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium avium infection, and enteric parasites in the past 5 years. A complete explanation of these variables is presented in detail elsewhere (Justice et al., unpublished data). A listing of the ICD-9-CM codes used is available on request. On the basis of the distributions, we categorized number of medical comorbidities as 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more comorbidities and number of HIV-related conditions as 0, 1, 2, and 3 or more HIVrelated conditions.

Health Care Use.

On the patient survey, we asked, “In the past 6 months, how many visits have you had to doctors outside of the VA?” From answers to this question, we calculated the percentage of veterans who had at least 1 visit to a non-VA physician in the past 6 months; we used administrative data to calculate the percentage of veterans who had 2 or more VA clinic visits within the past 6 months.

Clinical Management.

According to standard HIV treatment guidelines, persons receiving HAART should have their CD4 counts and viral load copies monitored every 3 months.9 In addition, those with a low CD4 count (< 200/mm3) should receive PCP prophylaxis.4 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) data were used to determine whether a patient was receiving HAART at baseline. We defined HAART as 3 or more antiretroviral medications. To evaluate whether treatment was being monitored appropriately, we used laboratory data to determine whether those on HAART received 4 or more CD4 laboratory tests per year and 4 or more viral load laboratory tests per year. We used PBM data to determine the percentage of patients on PCP prophylaxis (800 mg of sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg of trimethoprim) of those with a low CD4 count (< 200/mm3).

Adherence to HIV Medication.

We evaluated patients’ adherence to HIV medication with the following questions from the patient survey: “During the past 4 days, on how many days have you missed taking any of your doses?” “Did you miss any of your anti-HIV medication last weekend—last Saturday or Sunday?” “When was the last time you missed any of your HIV medication?”8 These questions are from a validated instrument used by the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group.10 For each of these questions, we combined responses to create dichotomous variables representing perfect adherence and imperfect adherence.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare age between nationally identified HIVpositive–veteran data and VACS 3 data; χ2 tests were used to compare race and gender. Mortality rates were calculated and compared between nationally identified HIV-positive veterans (restricted to patients identified at outpatient visits) and VACS 3 veterans using Cox proportional hazards models with adjustment for race and age.

Nationally Identified HIV-Positive Veterans

Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare survival by race. Patient follow-up time was the difference between the first HIV diagnosis date and either the date of death or the date of the most recent inpatient or outpatient visit. We calculated hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), controlling for age. Models were estimated with White veterans as the baseline category and the χ2 test was used to compare hazard ratios of Black and Hispanic veterans. In addition, we produced survival curves by race, controlling for age.

To determine whether being identified as HIV positive at an inpatient or outpatient visit varied by race, the χ2 test was used. We then compared survival by race, restricting the sample to those identified as HIV positive at an outpatient visit, with Cox proportional hazard models as described above.

VACS 3

To examine health status, health care use, clinical management, and adherence to HIV medication by race, dichotomous variables were compared using χ2 tests or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Cox proportional regression analyses were carried out to compare survival by race. For all analyses, a P value of .05 or less was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

National Descriptive Statistics

The median age for the 5676 nationally identified HIV-positive veterans was 49 years; 44% were White, 47% were Black, and 9% were Hispanic. Ninety-seven percent were male (Table 1 ▶).

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of HIV-Positive Veterans: National and Veterans Aging Cohort 3-Site Study (VACS 3)

| National (n = 5676) | VACS 3 (n = 865) | P | |

| Median age, y (range) | 49 (25–85) | 50 (29–79) | < .001 |

| Race, % | < .001 | ||

| White | 44.4 | 33.8 | |

| Black | 47.1 | 54.2 | |

| Hispanic | 8.5 | 12.0 | |

| Male, % | 96.8 | 98.7 | .002 |

| Ever homeless, % | — | 30.4 | — |

| Mental illness, % | — | 10.3 | — |

| Currently smokes, % | — | 54.1 | — |

| Intravenous drug use exposure, % | — | 33.4 | — |

| Mortality rate, unrestricteda | |||

| White | 5.4 | — | — |

| Black | 6.7 | — | — |

| Hispanic | 7.1 | — | — |

| Overall | 6.1 | — | — |

| Mortality rate, restricteda,b | |||

| White | 4.3 | 3.1 | .6 |

| Black | 4.5 | 4.1 | .7 |

| Hispanic | 4.9 | 5.2 | .4 |

| Overall | 4.4 | 3.8 | .8 |

aCalculated as number of deaths per 100 person-years.

bNational data restricted to n = 4801 identified at outpatient visits.

National Mortality

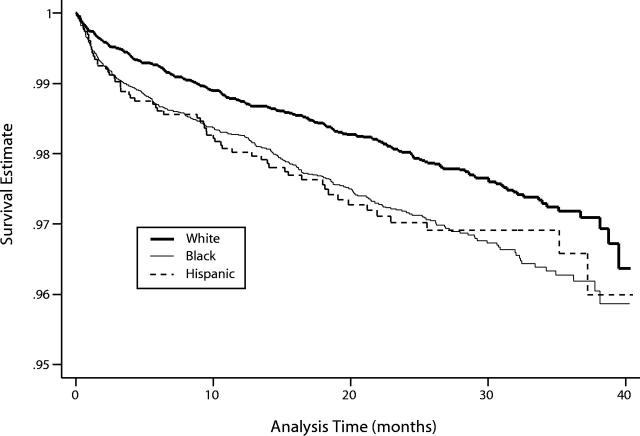

The overall mortality rate of the nationally identified HIV-positive veterans was 6.1 per 100 person-years (Table 1 ▶). Black and Hispanic veterans were more likely than White veterans to have been first identified as HIV positive at an inpatient visit (20% and 16% vs 11%; P < .001). When we restricted the analysis to 4801 patients who were identified at an outpatient visit, the mortality rate was 4.4 per 100 person-years (Table 1 ▶). In Cox proportional hazards survival analysis of the unrestricted data, Black and Hispanic veterans had statistically significantly higher mortality rates, after control for age, compared with White veterans (HR = 1.41 [95% CI = 1.19, 1.66] and HR = 1.41 [95% CI = 1.06, 1.86], respectively). Mortality rates of Black and Hispanic veterans were not significantly different from each other. We show the survival curves by race, adjusted for age, in Figure 1 ▶. When the analysis was restricted to patients identified at outpatient visits, the pattern was similar.

FIGURE 1—

Survival estimates for nationally identified HIV-positive veterans, controlled for age (n = 5676).

VACS 3 Participants Compared With Nationally Identified HIV-Positive Veterans

VACS 3 participants were slightly older, more likely to be male, and less likely to be White compared with nationally identified HIV-positive veterans (Table 1 ▶). Mortality rates (both overall and stratified by race) were similar between VACS 3 and nationally identified HIV-positive veterans identified at outpatient visits (Table 1 ▶).

VACS 3 Health Status

Providers estimated that 28% of White veterans had a 90% to 100% chance of being alive in 5 years, compared with 22% of Black veterans and 14% of Hispanic veterans (P = .008). Forty-one percent of Hispanic veterans had a low CD4 count, compared with 24% of White veterans and 28% of Black veterans (P = .004). Detectable viral load did not differ by race (Table 2 ▶).

TABLE 2—

Health Status, Use of Clinic Services, Disease Management, and Medication Adherence in Veterans Aging Cohort 3-Site Study (VACS 3), by Race

| Overall (%) | White (%) | Black (%) | Hispanic (%) | P | |

| Health status | |||||

| Greater than 90% probability of being alive at 5 years (provider prognosis)a | 23.0 | 28.4 | 21.5 | 14.4 | .008 |

| CD4 count < 200b | 28.2 | 24.3 | 27.7 | 41.4 | .004 |

| Viral load > 500b | 53.5 | 53.1 | 53.5 | 54.8 | .9 |

| No. of medical comorbidities | < .001 | ||||

| 0 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 8.3 | 10.6 | |

| 1 | 17.6 | 23.6 | 14.1 | 16.4 | |

| 2 | 17.9 | 24.0 | 14.5 | 16.4 | |

| 3 | 17.0 | 13.7 | 19.8 | 13.5 | |

| ≥ 4 | 38.0 | 27.7 | 43.3 | 43.3 | |

| No. of HIV conditions | .002 | ||||

| 0 | 54.5 | 60.6 | 53.1 | 43.3 | |

| 1 | 21.7 | 20.0 | 22.6 | 22.1 | |

| 2 | 11.3 | 12.0 | 10.7 | 12.5 | |

| ≥ 3 | 12.5 | 7.2 | 13.7 | 22.1 | |

| Clinic use | |||||

| 1 or more non-VA visitsc | 28.9 | 33.2 | 27.1 | 25.0 | .1 |

| 2 or more clinic visits in past 6 monthsd,e | 84.4 | 80.1 | 86.1 | 89.8 | .04 |

| Disease management | |||||

| On HAARTf,g | 82.2 | 82.5 | 80.4 | 89.4 | .09 |

| 4 or more CD4 labs in past yearb,e | 77.9 | 80.5 | 76.1 | 78.5 | .4 |

| 4 or more viral load labs in past yearb,e | 80.6 | 84.2 | 78.8 | 78.5 | .2 |

| PCP prophylaxisb,h | 57.8 | 56.3 | 56.2 | 65.1 | .6 |

| Adherence to HIV medication | |||||

| Missed no doses over past 4 daysc,i | 68.0 | 71.8 | 66.1 | 65.6 | .3 |

| Missed no doses last weekendc,i | 77.6 | 80.6 | 75.6 | 78.5 | .3 |

| Never missed any dosesc,i | 27.4 | 22.5 | 29.7 | 30.5 | .1 |

Note. HAART = highly active antiretroviral therapy; PCP = Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia.

aFrom baseline provider survey.

bFrom laboratory data.

cFrom baseline patient survey.

dFrom administrative data.

eOf those who were on HAART according to Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) data (n = 707).

fFrom PBM data.

gOf those with a CD4 count < 200/mm3 (n = 242).

hPatient on 3 or more antiretroviral medications at baseline.

iOf those who reported taking medication for HIV (n = 861).

Higher proportions of Black and Hispanic veterans than of White veterans had 4 or more medical comorbidities (43% and 43% vs 28%; P < .001) (Table 2 ▶). Black and Hispanic veterans were more likely than White veterans to have 3 or more HIV conditions (14% and 22% vs 7%; P = .002).

VACS 3 Health Care Use

White veterans were more likely to have had 1 or more non-VA visits (33%) than were Black (27%) and Hispanic (25%) veterans; however, this difference was not statistically significant. Of those on HAART, a higher proportion of Black and Hispanic veterans than of White veterans had 2 or more VA clinic visits within the last 6 months (86% and 90% vs 80%; P = .04) (Table 2 ▶).

VACS 3 Clinical Management

There was no statistically significant difference by race between the percentages of patients on HAART: 89% of Hispanic, 83% of White, and 80% of Black veterans. Of veterans on HAART, no significant differences were found by race in proportions of patients with 4 or more CD4 count and viral load laboratory tests in the past year, and for veterans with a low CD4 count, no significant difference was found by race in proportions on prophylaxis for PCP (Table 2 ▶).

VACS 3 Adherence to HIV Medication

For all 3 patient-reported adherence measures, there were no significant differences by race for patients on HIV medication (Table 2 ▶).

DISCUSSION

Nationally, minority HIV-positive veterans have mortality rates that are approximately 40% higher than those of White HIV-positive veterans. Similarly, minority veterans in VACS 3 had higher mortality rates. In contrast, Jha and colleagues found that Black patients admitted to the VA for common medical diagnoses (not including HIV infection) had lower mortality rates than did White veterans.11

In VACS 3, minority veterans had a poorer prognosis (as assessed by providers), a greater burden of medical comorbidities and HIVrelated conditions, and lower CD4 counts at enrollment compared with White HIVpositive veterans in care. Furthermore, national data revealed that minority veterans were more likely to have been first diagnosed with HIV as inpatients. These combined results indicate that within the VA, minority veterans are diagnosed with HIV later in their illness and are sicker in general at the time of HIV diagnosis than are White veterans. This finding is important for 2 reasons. First, it may partially explain poorer survival. If minority veterans with HIV infection are coming in for care later, the real differences in survival may be overstated. However, seeking care later in the course of HIV illness has serious implications. If patients do not receive triple-drug therapy before their CD4 cell count falls below 200/mm3, their survival benefit is compromised.12,13 Thus, delayed treatment likely leads to real differences in absolute survival. Second, the general trend in VA care is that minority veterans come in for care earlier in the course of disease than do White veterans because they have fewer health care options outside the VA. For example, the findings of Jha and colleagues suggest that Black veterans are less severely ill than White veterans on admission to the VA for general medical conditions.11

One must wonder why this pattern does not appear to be the case in HIV-infected veterans. Ironically, 1 possibility is that minority veterans may already be in care at the time they contract HIV, but because their providers are focused on the chronic disease that initially brought the veteran into care, they may attribute the early signs of HIV infection (fatigue, weight loss, diarrhea, anemia) to preexisting disease, thereby delaying diagnosis of HIV infection. If this is true, the problem is likely to become more pronounced as an increasing proportion of older individuals contract HIV infection.14 Redelmeier and colleagues have demonstrated that among older patients, providers often fail to optimally manage unrelated medical conditions when a patient is already in care for a major chronic disease.15

We found no evidence of significant racial differences in clinical management or in adherence to HIV medication. Minority veterans were seen more often for VA care than were their White counterparts, as might be expected because of their greater severity of illness. This finding supports Harada et al.’s finding that Black veterans used more VA outpatient services than did White veterans.16

Our study has important strengths. By using national administrative data, our study was sufficiently powered to compare survival among White, Black, and Hispanic veterans. To identify health differences by race, we used in-depth prospective cohort data to compare measures of health status, clinic use, clinical management, and medication adherence. We would not have been able to compare all of these aspects of health and health-related factors if our study had been limited to administrative data. The national veteran administrative data and VACS 3 data predominantly concern minorities, and the median ages of the cohorts are 49 and 50 years, respectively, reflecting the changing population of those infected with HIV.

Limitations to this study exist. Our analyses were unable to address health care issues of veterans using care outside the VA system. Although we assumed that everyone in the study had equal health coverage through the VA, it is likely that some patients experienced barriers in accessing this care and that other patients may have received additional care outside the VA Healthcare System. HAART is available at minimum cost within the VA. In addition, education and income likely play a role in health status, health care use, and survival, but we were unable to evaluate this role, because data were not available.

The race data used for nationally identified HIV-positive veterans in care were obtained from the administrative database, and the race data used in VACS 3 were primarily obtained from the provider survey. According to a study by Boehmer et al., race derived from administrative data is correctly classified (self-reported race is the gold standard) 77% of the time for White, 69% of the time for Black or African American, and 61% of the time for Spanish, Hispanic, and Latino veterans.17 However, when evaluating processes of care, differences by race are likely the result of differential treatment by the provider on the basis of racial discrimination. Therefore, for the purposes of evaluating processes of care, the provider’s perception of race may be more relevant than the patient’s actual race.

We were limited in the extent to which we could use the VA administrative data to address our research questions. We could not examine or control for the number of medical comorbidities or HIV conditions present at the time of HIV/AIDS diagnosis.

Interventions need to be implemented to encourage minorities to seek regular medical care, to persuade those at risk of HIV to be tested before symptoms are advanced, and to alert providers of the importance of HIV screening among minority patients with other chronic diseases.

Future research will focus on identifying and evaluating medical comorbidities and HIV conditions and on examining health care use and diagnoses made before the HIV/AIDS diagnosis and will use the national administrative data. By focusing on comorbidities and use before an HIV/AIDS diagnosis, we hope to gain insight into the reasons that minority veterans are sicker at the time of diagnosis—whether they are seeking care later in HIV disease, are sicker with other medical comorbidities in general, or are in care but receive a delayed diagnosis from their providers. Only when we understand these factors can we begin to address them to reduce and eventually eliminate racial disparities in processes of care and health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcohol Abuse (grant U01 AA 13566); the National Institute of Aging (grant K23 AG00826); the Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Faculty Scholar Award; an inter-agency agreement between the National Institute of Aging and the National Institute of Mental Health (to A. C. Justice); unrestricted educational grants from GlaxoSmithKline Inc and Agouron Pharmaceuticals; and the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System (to A. C. Justice). L. Rabeneck is a recipient of a Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health (K24 DK59318), and M. J. Fine is supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant K24 AI01769-04).

We thank the site principal investigators and survey coordinators for the Cleveland, Ohio; Houston, Tex; and Manhattan, NY, sites; the coordinating center staff; and especially the veterans who participated in this study. Without their contributions, this article would not have been possible.

Human Participant Protection Use of national administrative data was approved by the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and the University of Pittsburgh institutional review boards. Institutional review board approval was obtained from all 3 study sites and from the study center in Pittsburgh, Penn.

Contributors K. A. McGinnis conceived the analysis, designed and carried out all analyses, and led the writing. M. J. Fine provided editing and interpretative guidance. R. K. Sharma assisted in interpreting findings and provided background information. M. Skanderson and J. H. Wagner assisted by acquiring critical data with their programming expertise and helped in the interpretation of these data. M. Rodriguez-Barradas and L. Rabeneck played a critical role in data acquisition. A. C. Justice conceived the main study, supervised its implementation, and was involved with study design and critical revisions of the article.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.The National Initiative to Eliminate Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health: An Overview. Bethesda, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2001. Available at http://raceandhealth.hhs.gov. Accessed May 29, 2000.

- 2.Conigliaro J, Whittle J, Good CB, Skanderson M, Kelley M, Goldberg K. Delay in presentation for cardiac care by race, age, and site of care. Med Care. 2002;40(1 suppl):I97–I105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashton CM, Peterson NJ, Wray NP, Yu HJ. The Veterans Affairs medical care system: hospital and clinic utilization statistics for 1994. Med Care. 1998;36:793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro MF, Morton SC, McCaffrey DF, et al. Variations in the care of HIV-infected adults in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. JAMA. 1999;281:2305–2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fasciano NJ, Cherlow AL, Turner BJ, Thornton CV. Profile of Medicare beneficiaries with AIDS: application of an AIDS casefinding algorithm. Health Care Financing Rev. 1998;19:19–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher SG, Weber L, Goldberg J, Davis F. Mortality ascertainment in the veteran population: alternatives to the National Death Index. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Justice AC, Landefeld CS, Asch SM, Gifford AL, Whalen CC, Covinsky KE. Justification for a new cohort study of people aging with and without HIV infection. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(suppl 1):S3–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smola S, Justice AC, Wagner J, Rabeneck L, Weissman S, Rodriguez-Barradas M. Veterans aging cohort three-site study (VACS 3): overview and description. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(suppl 1):S61–S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dybul M, Fauci AS, Bartlett JG, Kaplan JE, Pau AK, Panel on Clinical Practices for the Treatment of HIV. Guidelines for using antiretroviral agents among HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Recommendations of the Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-7):1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG). AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jha AK, Shlipak MG, Hosmer W, Frances CD, Browner WS. Racial differences in mortality among men hospitalized in the Veterans Affairs health care system. JAMA. 2001;285:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egger M, May M, Chene G, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palella FJ Jr, Deloria-Knoll M, Chmiel JS, et al. Survival benefit of initiating antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons in different CD4+ cell strata. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:620–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ory M, Mack K. HIV/AIDS rates and trends among middle aged and older individuals. JAIDS. In press.

- 15.Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1516–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harada ND, Damron-Rodriguez J, Villa VM, et al. Veteran identity and race/ethnicity: influences on VA outpatient care utilization. Med Care. 2002;40(1 suppl):I117–I128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boehmer U, Kressin NR, Berlowitz DR, Christiansen CL, Kazis LE, Jones JA. Self-reported vs administrative race/ethnicity data and study results. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1471–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]