Abstract

Objectives. We describe the tobacco industry’s effort in Massachusetts to block the adoption of local regulations designed to reduce youth access to tobacco products. We also explain how state-funded tobacco control advocates overcame industry opposition.

Methods. We examined internal tobacco industry documents and records of local boards of health and conducted interviews with participants in local regulatory debates.

Results. The industry fought proposed regulations by working through a trade group, the New England Convenience Store Association. With industry direction and financing, the association’s members argued against proposed regulations in local public hearings. However, these efforts failed because community-based advocates worked assiduously to cultivate support for the regulations among board of health members and local community organizations.

Conclusions. Passage of youth access regulations by local boards of health in Massachusetts is attributed to ongoing state funding for local tobacco control initiatives, agreement on common policy goals among tobacco control advocates, and a strategy of persuading boards of health to adopt and enforce their own local regulations.

In Massachusetts, an aggressive tobacco control program has led many local boards of health to adopt stringent regulations designed to curb minors’ access to tobacco products. These regulations have been enacted in spite of an extensive, orchestrated campaign by the tobacco industry and a regional trade association to prevent them from being adopted. The success of this program, and the failure of its adversaries, affords an opportunity to understand both how the tobacco industry works to oppose the regulation of its products and how that resistance can be surmounted.

Over the past decade, persuading local governments to adopt and enforce such regulations has been an important, though controversial, strategy for combating adolescent smoking.1 While this approach can reduce youth purchases of cigarettes, it has not by itself been effective in reducing youth smoking,2,3 leading some to argue that it is counterproductive.4 It has, however, been shown to be a key component of broader, multifaceted community interventions that have curbed youth smoking.5

In states where such local tobacco control regulations have been advocated, the tobacco industry has employed an array of tools for blocking their adoption, including litigation and legislative preemption6 and working through political campaign firms, front groups, and business allies to mobilize local opposition to proposed regulations.7,8 The industry has also accused public health professionals of engaging in illegal lobbying activities.9 However, the Massachusetts experience demonstrates that, if public health advocates engage in the correct strategies, local initiatives can be successful in spite of such efforts.

In this article, we describe the political contest surrounding the adoption by local boards of health in Massachusetts of regulatory restrictions designed to reduce youth access to tobacco products. We outline how the New England Convenience Store Association (NECSA), with financial support and assistance from the tobacco industry, mobilized a grassroots network of retailers to oppose the adoption of these regulations. We then examine how public health advocates overcame that opposition. Finally, we draw from this account lessons for public health advocates seeking to achieve similar outcomes in other states or countries.

METHODS

The present research involved a combined quantitative–qualitative design. We derived quantitative data on the number of local communities that adopted youth access regulations between 1990 and 2000 from information gathered by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH). These data reveal the degree to which public health advocates have been successful in persuading local boards to pass tobacco control regulations in spite of industry opposition.

Qualitative descriptions of how these advocates overcame industry opposition were drawn from 3 sources. First, we reviewed previously confidential internal tobacco industry documents (found at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu) that referred to NECSA. We examined these documents for descriptions of the nature of the NECSA–tobacco industry alliance and its political tactics.

Second, we conducted a series of semistructured interviews with tobacco control advocates who had worked for a state- or region-wide organization and had participated in hearings throughout the state during the period of the study (1990–2000). We also interviewed the executive director of NECSA. We selected these individuals because they were active participants in local regulatory debates throughout the state during this period. They were interviewed in regard to both their tactics and the larger dynamics of the political battle over youth access regulations, particularly as it played out in the key decisionmaking forum of local board of health hearings.

Finally, we examined records of hearings of local public health boards that had enacted regulations. Decisions as to whether to include particular hearings were based on the clarity with which the records of the hearings illuminated and elaborated upon the tactics described in the industry documents reviewed and the interviews conducted.

RESULTS

The Tobacco Industry’s Reaction to Public Health Activism

In 1992, Massachusetts voters passed a ballot initiative, labeled Question 1, that raised the state’s excise tax on cigarettes by 25 cents and the tax on smokeless tobacco by 25% of its wholesale price to provide funding for tobacco education programs.10 The state legislature appropriated Question 1 funds to the DPH to create and administer the Massachusetts Tobacco Control Program, a set of activities and services designed to “reduce the public health risks of tobacco use.”11(pv) Among these activities were efforts to promote the adoption, at the local level, of regulations designed to prevent youth access to tobacco products.

Shortly after the passage of Question 1, Kurt L. Malmgren, the Tobacco Institute’s senior vice president of state activities, offered the following observation in a confidential memorandum to the organization’s president:

We face increasingly serious challenges at the local level of government in the areas of smoking bans, point-of-sale display bans and restrictions, punitive retailer licensing schemes, sampling/couponing bans, advertising bans and many other related issues. The anti-tobacco forces have developed a more sophisticated and well-funded structure to address local government affairs.12

More than a year after the passage of Question 1, in a draft document to be presented at a corporate affairs conference, Philip Morris vice president for state government affairs Tina Walls wrote that tobacco control advocates, now supported by state funds, were targeting local communities. “[T]he anti-smoking movement [has] adopted a ‘PAC-man’ strategy where they attempt to gobble up one community at a time.”13

The industry viewed this state-sponsored local activism with alarm. The extensive advocacy infrastructure that was made possible by state funding enabled regulatory advocates to prompt local health boards to consider restrictions on tobacco at a faster pace than the industry could respond. Philip Morris vice president Walls complained that the “antismoking” forces “can be in more places than we can.”13

A compounding problem was that, from the industry’s perspective, these local proposals were being deliberated upon in the wrong venue: local boards of health. Kurt L. Malmgren complained, “Boards of health in the Commonwealth are un-elected, authoritarian bodies. It is difficult for the industry to make its voice heard in their decision-making process.”12

The Industry’s “Run Silent, Run Deep” Strategy

In response to this heightened “antismoking” activism, the industry focused its attention on identifying and defeating local regulatory proposals. Tobacco Institute vice president Malmgren concluded that, after the passage of Question 1, “close staff attention [must be paid] to the myriad of complex and extremely punitive anti-tobacco measures at the local level.”12 Even more important was developing “a solid coalition of willing and able home-town allies” through which the industry could work to block local regulations.12

In Massachusetts, NECSA became the industry’s ally. This organization’s membership consisted of the owners and operators of retail stores located throughout the state, thereby providing the industry with a ready-made grassroots network. Moreover, NECSA members had a powerful incentive to oppose such restrictions, in that many of their businesses received direct payments from tobacco corporations for prominent display of their products (Donald J. Wilson, director, Municipal Tobacco Control Technical Assistance Program, Massachusetts Municipal Association, oral communication, December 2001).

The industry moved to establish a formal alliance with NECSA even before Question 1 passed. In his confidential memorandum, Tobacco Institute vice president Malmgren declared that “earlier this year the industry established a formal, solid working relationship” with the association.12 This strategy, dubbed “run silent, run deep” in another state, enabled the industry to actively participate in efforts to defeat local ordinances while avoiding the assumption of a public role.

The initial role assumed by NECSA members in this alliance was that of an “early warning network,” as described by Philip Morris regional manager Jim Pontarelli: “Working with [NECSA], we developed a network whereby local retailers would serve as our eyes and ears in every Massachusetts community.”13 A detailed explanation of how this network operated is provided in a document proposing its formal creation. Printed on NECSA letterhead, the “Proposal to Coordinate a Community Outreach Project to Oppose Local Regulations of Tobacco Sales” outlined a plan whereby NECSA would designate, in 15 metropolitan areas (later expanding to 30 additional communities), local business owners or executives to serve as “monitors” of their local governments. They would read legal notices daily, look in municipal buildings for notices of public hearings, and immediately alert NECSA of any proposed restrictions on tobacco retailing.14

According to Philip Morris regional manager Pontarelli, NECSA staff and industry representatives provided these monitors with formal training in their tasks: “We taught them how to prowl the corridors of town halls reading bulletin boards. We showed them how to search local newspapers for notices of public hearings. Most importantly, we taught them how to pick up the telephone and dial our number when they spotted something.”13

The industry also moved to enlist all NECSA members as more informal “fire-spotters.” According to a memorandum from an R. J. Reynolds vice president to the company’s CEO, “[T]he New England Convenience Store Association has agreed to join with us in mailing all Bay State cigarette retailers (on NECSA’s letterhead), asking them to be on the alert for damaging ordinances likely to be introduced in local communities.”15 The tobacco industry’s own sales representatives in the state also checked for notices of proposed hearings and provided that information to NECSA (Catherine Flaherty, executive director, NECSA, oral communication, January 2002).

This early warning system was regarded as crucial because it enabled the industry to react quickly. The text of a Philip Morris presentation on the industry’s “political challenges” declared, “Often a smoking ban or other law can be stopped [emphasis in original] if we can get somebody on the scene to testify or mobilize retailers.”16 Such a role was one that convenience store owners and officers were uniquely suited to play, according to the NECSA proposal. “Local merchants are local leaders, and their involvement in working together on these issues can be a crucial factor in developing public opinion.”14

To realize this potential, NECSA members were taught how to mobilize local retailers and given assistance and guidance in doing so by NECSA staff. In training provided by the Tobacco Institute, monitors were to be given lists of city officials and legislators and taught “[s]pecific steps needed to coordinate a local grass-roots effort.”14 Once a proposed regulation was spotted, NECSA would “[a]ctively recruit retailers to get involved in fighting the restrictions” and prepare for them “sample letters, talking points, and economic impact summaries.” Furthermore, a NECSA staff member would “[a]ttend all public hearings related to tobacco proposals.”14

The Weight of Industry Resources

The tobacco industry also provided resources in support of efforts to defeat local regulations. The industry’s “goals and tactics” for responding to local challenges in Massachusetts and other states are outlined in a memorandum written by Tobacco Institute vice president Kurt L. Malmgren: “[e]xpand use of [the Tobacco Institute’s] media relations staff to brief local media on behalf of the industry, and to provide assistance to local allies and coalitions with regard to media contacts. Assistance may include advice in drafting letters to the editor or press releases, or provision of media training for certain allies.”12 Furthermore, “the industry is prepared to deliver direct mail, run phone bank operations and otherwise attack local proposals with our local business allies in a generally coordinated and productive fashion.”12 Finally, “[l]ocal consultants and resources—bolstered by the state activities legislative analyst team’s ability to provide immediate assistance with locally-specific economic analyses, bill amendments and other input—can make for an effective approach to the local challenge.”12

The industry also managed the overall effort to defeat local ordinances in Massachusetts as well as other states. The Tobacco Institute memorandum proposed that the institute “employ regional managers of community affairs to oversee the local operation.” These regional managers were to “work directly with member company personnel and allies to formulate local strategies and to coordinate the use of necessary resources and other components of the program.”12 According to Jim Pontarelli (Philip Morris regional manager), “The actual mobilizations and local lobbying [are] managed by a team that includes people from RJR, US Tobacco, a representative from [NECSA] and several others.”13

Finally, the industry provided financing for this antiregulatory campaign. According to the executive director of NECSA, “During that time, the Tobacco Institute did help fund our initial tobacco monitoring program” (Catherine Flaherty, executive director, NECSA, oral communication, January 2002). Tobacco Institute vice president Malmgren’s memorandum noted that “[f]or monitoring purposes, we fund our allies in the convenience store group.”12 In addition, a handwritten note on a slide prepared for a marketing seminar read as follows: “Meetings were held with representatives of [NECSA and other organizations],” and subsequently “we have provided support to these organizations.”17 The scope of this financial support is suggested by an itemized budget produced on NECSA letterhead that projected a total cost of $25 000 for the first 7 months of the monitoring project.14

Failure of the Alliance and the Adoption of Youth Access Regulations

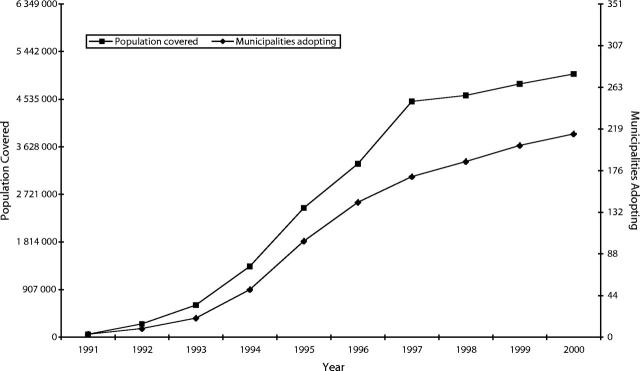

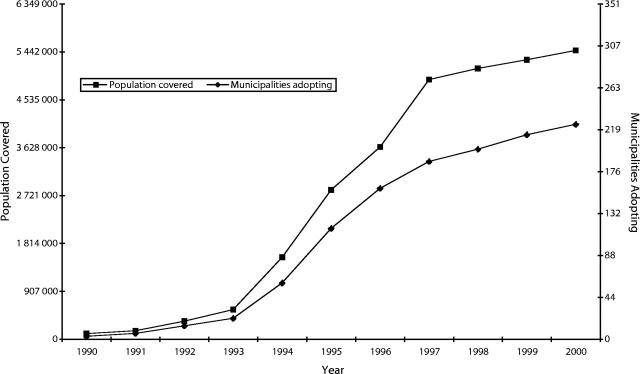

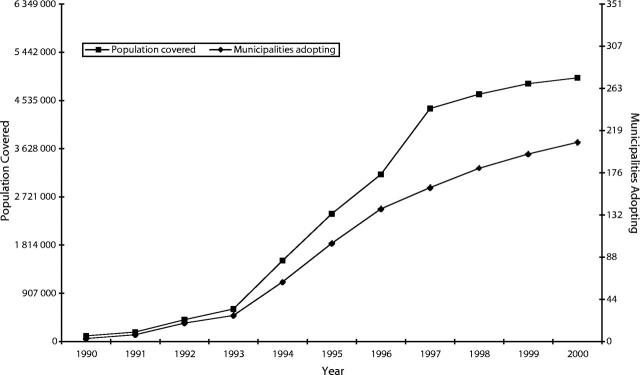

The industry documents reviewed reported instances in which organized local opposition efforts persuaded a board of health not to adopt a proposed regulation. However, a comprehensive review of the adoption of youth access regulations by boards of health reveals that such tobacco industry victories were the exception. Figures 1 ▶ through 3 ▶ chart the adoption over time by local boards of health of 3 different classes of youth access regulations: limitations on in-store displays, fines levied against retail establishments charged with selling to minors, and municipal licensing requirements for selling tobacco products. All of these regulations give retailers a financial incentive not to sell tobacco products to minors.

FIGURE 1—

Cumulative adoption of limits on in-store displays: 1991–2000.

Source. Massachusetts Department of Public Health

FIGURE 3—

Cumulative adoption of licensing of tobacco retailers: 1990–2000.

Source. Massachusetts Department of Public Health

Some two thirds of the communities in the state, encompassing more than three quarters of its population, have adopted these regulations. Furthermore, the pace of adoption accelerated after funding of the DPH tobacco control grants to local governments and nonprofit organizations beginning in 1993. The larger picture is one of failure for the industry and its allies and success for the state’s tobacco control initiative in passing regulations to prevent the sale of tobacco products to minors.

Roles of the Massachusetts Tobacco Control Program, Local Boards of Health, and Tobacco Control Advocates

The tobacco industry–NECSA alliance failed because of the actions of key public and private actors working, with the support of DPH grants, to foster the adoption of tobacco control regulations. The most important of these actors were local boards of health. These bodies have a broad legal mandate to protect the public’s health and safety, and they are legally charged with weighing in their decisionmaking only those considerations.

Local boards were enticed into hiring tobacco control staff by the DPH’s tobacco control grants. As a participant in the process explained, “[L]ocal boards of health looked at it as ‘oh, it’s a grant. Let’s apply for this grant. So now, what do we have to do, now that we’ve got it?’ ” (Cheryl Sbarra, director, Tobacco Control Program, Massachusetts Association of Health Boards, oral communication, December 2001). The grants dictated that local boards use those community members they had hired as their staff to assist them in enacting and enforcing tobacco control regulations, of which youth access was an initial priority.

The public health professionals on these boards were supportive of DPH’s tobacco control initiative. However, board members were reticent to act in an area that was outside of their traditional purview, and one in which they had not previously asserted their legal authority. One tobacco control staff official recalled: “In the beginning, people weren’t just like, ‘hey, nice to meet you, let’s pass policy.’ People were afraid of policy. They were afraid of passing their regulation beyond state law, even though they had the authority to do it” (Joan E. Hamlet, director, Boards of Health Tobacco Control Alliance, oral communication, December 2001).

Grant-funded staff aides began to overcome this reluctance by engaging in the tasks mandated by the tobacco control grants. One of the most important of these tasks was gathering evidence showing that youth access to tobacco products was a community problem. They hired youths to conduct compliance checks on local merchants and then reported the frequently high violation rates observed to the local board.

Staff officials undertook other tasks that also laid the groundwork for regulatory action by local boards. They conducted telephone and residential surveys to assess community support for youth access regulations and shared the typically positive results with board members. They also met with school- and community-based groups to raise the profile of the problem of youth smoking and conducted education sessions with local merchants. Once boards agreed to consider adopting a youth access regulation, they would make preparations for public hearings on that regulation (Donald J. Wilson, director, Municipal Tobacco Control Technical Assistance Program, Massachusetts Municipal Association, oral communication, December 2001).

These officials were also able to insulate board members from the anger of local opponents of regulations. When board members received telephone calls from opponents, they would refer the calls to their grant-funded staff. A staff official explained, “[W]e’d keep a complaint log. And then we’d report back to the board, ‘we got five calls complaining.’ But they didn’t hear people’s voice in the heat of it” (Joan E. Hamlet, director, Boards of Health Tobacco Control Alliance, oral communication, December 2001).

Officials were also able to counter more formidable challenges, such as when opponents would threaten to sue a health board. According to the same staff official, board members would voice worries such as “if we get sued, we’re going to be using town money. We’re going to have to answer to townspeople to use their money for this.” The staff would then respond, “ ‘Wait a minute, we can help you out here, we’ll research this, we can get it thrown out in the first case.’ So that’s how we’ve calmed the board down” (Joan E. Hamlet, director, Boards of Health Tobacco Control Alliance, oral communication, December 2001).

The same official also described more direct efforts to persuade both members of boards of health and other local officials of the merits of a regulation: “We’ve had to work on each individual board member to get them to come around. And what we do is, if they said ‘no,’ we’d say, ‘why is your answer no?’ and then whatever their reason was, we’d work to find information to help change that ‘no’ into a ‘yes’ ” (Joan E. Hamlet, director, Boards of Health Tobacco Control Alliance, oral communication, December 2001).

The second set of advocates, community coalition coordinators, was hired by local nonprofit organizations with funding from tobacco control grants. Coordinators preached the gospel of tobacco control to grassroots organizations within their community. One advocate explained, “They would get student health advisory councils, chambers of commerce, maybe a local hospital, parent-teachers organization, libraries, Scouts. Just go through the front pages of your local phone book, and all of those organizations, they would try to have them on board” (Cheryl Sbarra, director, Tobacco Control Program, Massachusetts Association of Health Boards, oral communication, December 2001). They also collaborated with board staff to counter any anticipated local opposition. As a board official explained:

We went and talked to all the merchants, we went and talked to all the key players. “This one’s for us, this one’s against us. This one’s really mad about it. These are the things they said to us outside of a public hearing, so they may come up at a public hearing.” So we could give those points, with suggested rebuttals to the coalition. And then the coalition’s job would be to find community citizens that would come and speak to these points. And they did (Joan E. Hamlet, director, Boards of Health Tobacco Control Alliance, oral communication, December 2001).

The third set of actors funded by tobacco control grants to work with local health boards was the Community Assistance Statewide Team (CAST). This organization consisted of attorneys from 2 professional organizations, the Massachusetts Municipal Association and the Massachusetts Association of Health Boards, as well as the Tobacco Control Resource Center at the Northeastern University School of Law. These attorneys assisted boards in drafting and revising proposed youth access regulations and ensuring, according to one participant, that the regulations met “legal muster” (Cheryl Sbarra, director, Tobacco Control Program, Massachusetts Association of Health Boards, oral communication, December 2001).

The more important role of these attorneys was to reassure uncertain board members and other local officials. According to one Massachusetts Association of Health Boards attorney, “They’ve seen me in other contexts. They’ve seen me at the certification training that [the association] does every year. So they feel like they’re getting good information. . . . It’s coming from their trade association. So it gives them the confidence that they need” (Cheryl Sbarra, director, Tobacco Control Program, Massachusetts Association of Health Boards, oral communication, December 2001). Similarly, local elected officials trusted the Massachusetts Municipal Association’s tobacco control attorney, who would work to garner their support for proposed regulations.

Local Public Hearings and the NECSA–Tobacco Industry Alliance

The efforts of all of these actors were focused on board of health hearings at which members of the public could offer comments on proposed regulations. These hearings were the last real obstacle to the enactment of regulations, because they involved the very real possibility that an organized “show of force” would persuade a board to withdraw or dilute a proposed regulation. The NECSA–tobacco industry network was, in many instances, successful in mobilizing merchants to attend public hearings on proposed regulations.

At these local hearings, merchants advanced a host of arguments in opposition to proposed regulations concerning the retailing of tobacco products, including economic ones. One merchant told a local board, “Cigarettes are a life line. If we lose cigarettes, we are out of business” (minutes of Wilmington Board of Health meeting, April 4, 1994). At another hearing, a spokesman for local merchants stated, “The tobacco industry pays the retailers extra for free standing displays. They could be losing thousands of dollars if they cannot have standing displays and will have to put them on the counter where they are controlled. It would be a severe economic hardship” (minutes of Natick Board of Health meeting, May 24, 1994). Merchants also argued that the loss of incentive allowances paid by tobacco companies would “mean eventual loss of jobs for employees” (minutes of Gloucester Board of Health meeting, February 17, 1994).

While board members were not unmoved by such arguments, they recognized their mandate not to weigh considerations other than the public’s health and safety in their deliberations. One board chair responded to a local merchant by saying, “[W]e sympathize with small business owners, but they have to think that in this case they are selling death. It may be legal, but it’s selling death. [I find] it very difficult to be sympathetic under these circumstances” (minutes of Ludlow Board of Health meeting, December 1, 1998).

Aware that board members had been well educated on the problem of youth smoking, opponents also offered a series of arguments that did not directly question the need for some sort of action. Several merchants stated that they should not be held solely responsible for a transaction that takes place between an employee and a customer. One owner complained at a hearing that “[t]here are no provisions in the regulations to punish the buyer. If an underage buyer comes into the store with a phony I.D., the store is penalized, not the buyer” (minutes of Westborough Board of Health meeting, June 13, 1996). Another argued that “the responsibility should be on the parents not on the [business] owner” (minutes of Framingham Board of Health meeting, September 2, 1997). An owner at a different hearing raised a host of objections, arguing that “sting operations were unfair, as well as the permit fee,” and that “[t]he proposed regulations are duplications of laws already in effect at the State level” (minutes of Westborough Board of Health meeting, June 13, 1996).

Finally, advocates attending hearings observed that opponents of regulations were, on occasion, able to delay or weaken a regulation simply by their large numbers and their demeanor at a hearing. One noted, “When it’s a really raucous, nasty, mean hearing, it’s very hard for the board of health to come out with strong regulations, because they feel like there’s a wave of ‘anti’ sentiment against what they’re doing” (Marc Boutin, vice president of government relations and advocacy, New England Division, American Cancer Society, oral communication, January 2002). Another stated, “[I]f we had a hearing, and it turned into a riot situation, the board would back off for a couple of months, so it really could delay policy from happening” (Joan E. Hamlet, director, Boards of Health Tobacco Control Alliance, oral communication, December 2001).

Role of Tobacco Control Advocates at Local Hearings

Grant-funded regulatory advocates were able to counter all of these arguments and tactics. Board staff would begin hearings by describing the extent of the problem of merchants selling tobacco to minors. The Natick board of health was told at a hearing that local youths conducting compliance checks for board staff “went to 36 locations and 17 locations sold to the minors. Four locations sold them cigarettes even after looking at the I.D.’s” (minutes of Natick Board of Health meeting, May 24, 1994).

Community coordinators arranged to have a diverse cross-section of community officials and organizations express their support for proposed regulations, either at board of health hearings or in letters to boards. The record of a Gloucester hearing reveals this strategy, listing 13 supporters of youth access regulations by name and organization, including several local doctors and nurses, an early childhood education teacher, a community health worker, a chamber of commerce representative, and an antismoking activist (minutes of Gloucester Board of Health meeting, February 17, 1994). Certain supporters were especially sought after. A coordinator explained, “You tried to have, if you could find, a business person, who perhaps had a store, who really was not upset about this, who would be willing to come and say ‘we think this is a good idea’ ” (Elaine Solivan, coordinator, COMMIT Coalition, oral communication, January 2002). Presentations by youth groups were also arranged.

CAST attorneys provided on-the-spot legal assistance to health boards as a means of facilitating their adoption of proposed regulations. More important, these attorneys were able to respond authoritatively to any legal challenges to boards’ authority. One attorney explained,

[I]t was very easy to intimidate a board of health into not passing regulations, because you would have, oftentimes, an attorney come and tell the board of health, “you don’t have the legal authority to do this.” So the board of health would say, “O.K.,” and they would scrap the regulations. With attorneys working for the Association, and providing the training, and showing up at the hearings, we could counter those specious arguments, and explain why they were wrong (Marc Boutin, vice president of government relations and advocacy, New England Division, American Cancer Society, oral communication, January 2002).

CAST attorneys also responded to the arguments made by merchants against regulations, thereby relieving board members of the responsibility of having to reject these arguments on their own (Marc Boutin, vice president of government relations and advocacy, New England Division, American Cancer Society, oral communication, January 2002).

Finally, both board staff and CAST attorneys worked with local boards before hearings to ensure that hearings were structured so as to minimize animosity directed toward boards. As one board official explained, “[T]obacco’s very passionate. So you have to set up rules, and say, ‘everybody speaks once, nobody can speak twice until everybody’s had an opportunity to speak once, one person speaks at a time.’ ” Board members were also instructed not to engage speakers in a debate. Then, “when someone would get up and say stuff, [the board] would say ‘Thank you very much, we’ll take that under advisement. Next. Thank you very much, we’ll take that under advisement’ ” (Joan E. Hamlet, director, Boards of Health Tobacco Control Alliance, oral communication, December 2001).

The benefit of the structured hearing was described by an advocate who stated, “When you had a hearing that was in control, the tone was with the proponents, but not the opponents.” Furthermore, “when there’s a calm, civil hearing, it’s pretty easy for the board of health to do the right thing” (Marc Boutin, vice president of government relations and advocacy, New England Division, American Cancer Society, oral communication, January 2002). The executive director of NECSA, conceding the effectiveness of these arrangements, characterized board hearings as “very orchestrated” in terms of the effort made to ensure that regulatory advocates would prevail in spite of any opposition expressed by local merchants (Catherine Flaherty, executive director, NECSA, oral communication, January 2002).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The Changed Political Landscape

In Massachusetts, the adoption of youth access regulations by local boards of health was principally due to the thorough advocacy efforts of regulatory proponents. Importantly, these efforts, funded by tobacco control grants, preceded those of the NECSA–tobacco industry alliance. The grassroots machinery developed by that alliance was sophisticated and extensive, but it was applied in communities only after public hearings had been scheduled. By that time, advocates had typically spent months laying the groundwork for affirmative board action, working both inside of government, with board members and elected officials, and outside of government, among grassroots community groups. As a result, when merchants expressed their opposition to proposed regulations at a public hearing, their objections were turned aside by a confident board of health and by a broad and well-organized show of community support for its proposed regulations.

Furthermore, the ongoing passage of youth access regulations had the cumulative effect of breaking the back of the tobacco industry–NECSA alliance. Advocates described intense opposition to youth access regulations when they were first proposed; however, after the first wave of enactments by local boards, this opposition largely dissipated. Subsequently, passage of such regulations became much less controversial and thus became the norm across the state. Now, when local boards either take up the issue for the first time or revisit existing regulations to make them more stringent, there is typically very little controversy or opposition (Joan E. Hamlet, director, Boards of Health Tobacco Control Alliance, oral communication, December 2001).

Lessons of a Successful Advocacy Campaign

This case study offers important lessons for public health advocates working to advance tobacco control regulations in other states or countries. First, there should be a reliable source of funding over an extended period of time for tobacco control initiatives. An important factor behind the success of the Massachusetts effort was the ongoing funding that stemmed from passage of Question 1.

Second, funding of advocacy efforts should be tied to specific regulatory outcomes, such as fines for retail sales to minors, providing tobacco control advocates a set of common goals around which to organize their efforts. The DPH tobacco control grants emphasized the common goal of adoption of youth access regulations, thereby increasing the effectiveness of the advocacy community as a whole.

Third, advocacy efforts should be focused on persuading local regulatory bodies to adopt and enforce their own regulations. DPH used grants to persuade local boards to adopt regulations on their own. As a result, local boards of health were able to “take ownership” of these regulations and tailor them to their community. Advocacy activities also built community support for the regulations.

Fourth, it is important to incorporate into the advocacy community respected organizations not directly associated with tobacco control. Both the Massachusetts Municipal Association and the Massachusetts Association of Health Boards had credibility with local officials that extended beyond the realm of tobacco control. Their support for youth access regulations carried extra weight with board members and other local officials.

Finally, the advocacy community should include actors that work directly with local health boards and actors that focus on local public opinion. In Massachusetts, tobacco control staff and CAST worked directly with local boards of health to foster adoption of youth access regulations, and community coordinators worked among local organizations to build public support for regulations. It was the combined influence of these mutually reinforcing efforts that resulted in the adoption of regulations reducing youth access to tobacco products.

FIGURE 2—

Cumulative adoption of fines for selling to minors: 1990–2000.

Source. Massachusetts Department of Public Health

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA86314-03).

Human Participant Protection Institutional review board approval was not required. This article cites local public officials and spokespersons for nonprofit organizations who agreed to on-the-record interviews. Other information cited was drawn from publicly available documents.

Contributors B. S. Andersen conducted the qualitative research and wrote the article. M. E. Begay conceived of and supervised the study, gathered qualitative data, and edited the final article. C. B. Lawson conducted the quantitative research.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Jacobson PD, Lantz PM, Warner KE, Wasserman J, Pollack HA, Ahlstrom AK. Combating Teen Smoking: Research and Policy Strategies. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Press; 2001:196–222.

- 2.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Youth access interventions do not affect youth smoking. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1088–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rigotti NA, DiFranza JR, Chang YC, Tisdale T, Kemp B, Singer DE. The effect of enforcing tobacco-sales laws on adolescents’ access to tobacco and smoking behavior. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1044–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ling PM, Landman A, Glantz SA. It is time to abandon youth access tobacco programmes: youth access has benefited the tobacco industry. Tob Control. 2002;11:3–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forster JL, Murray DM, Wolfson M, Blaine TM, Wagenaar AC, Hennrikus DJ. The effects of community policies to reduce youth access to tobacco. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1193–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Traynor MP, Begay ME, Glantz SA. New tobacco industry strategy to prevent local tobacco control. JAMA. 1993;270:479–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritch WA, Begay ME. Strange bedfellows: the history of collaboration between the Massachusetts Restaurant Association and the tobacco industry. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:598–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dearlove JV, Glantz SA. Boards of health as venues for clean indoor air policy making. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bialous SA, Fox BJ, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry allegations of “illegal lobbying” and state tobacco control. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiser PF, Begay ME. The campaign to raise the tobacco tax in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:968–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norton GD, Hamilton WL. Independent Evaluation of the Massachusetts Tobacco Control Program, Sixth Annual Report, January 1994 to June 1999. Cambridge, Mass: Abt Associates Inc.

- 12.Tobacco Institute. Confidential memorandum from Kurt L. Malmgren, senior vice president of state activities, to Samuel D. Chilcote, president. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. 30November1992. Bates No. 2023965875/5887. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu. Accessed May 10, 2001.

- 13.Draft corporate affairs conference presentation 5, remarks by Tina Walls, vice president, Philip Morris State Government Affairs, Jim Pontarelli, Philip Morris regional director for New England, et al. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. 12July1994. Bates No. 2040235793/5914. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu. Accessed May 12, 2002.

- 14.New England Convenience Store Association. Proposal to coordinate a community outreach project to oppose local regulations of tobacco sales. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. 19August1992. Bates No. 512695605/5610. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu. Accessed May 13, 2001.

- 15.Interoffice memorandum from Tom C. Griscom, executive vice president, external relations, to Jim Johnston, CEO of domestic tobacco. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. 13September1991. Bates No. 507746993/6996. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu. Accessed May 13, 2001.

- 16.Draft LEAP notes. Philip Morris Tobacco Company. 19October1994. Bates No. 2040236770/6792. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu. Accessed May 12, 2001.

- 17.Marketing issues seminar presentation, with handwritten notes. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. 30April1992. Bates No. 512568430/8472. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu. Accessed May 13, 2001.