Abstract

Group II intron homing in yeast mitochondria is initiated at active target sites by activities of intron-encoded ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particles, but is completed by competing recombination and repair mechanisms. Intron aI1 transposes in haploid cells at low frequency to target sites in mtDNA that resemble the exon 1-exon 2 (E1/E2) homing site. This study investigates a system in which aI1 can transpose in crosses (i.e., in trans). Surprisingly, replacing an inefficient transposition site with an active E1/E2 site supports <1% transposition of aI1. Instead, the ectopic site was mainly converted to the related sequence in donor mtDNA in a process we call “abortive transposition.” Efficient abortive events depend on sequences in both E1 and E2, suggesting that most events result from cleavage of the target site by the intron RNP particles, gapping, and recombinational repair using homologous sequences in donor mtDNA. A donor strain that lacks RT activity carries out little abortive transposition, indicating that cDNA synthesis actually promotes abortive events. We also infer that some intermediates abort by ejecting the intron RNA from the DNA target by forward splicing. These experiments provide new insights to group II intron transposition and homing mechanisms in yeast mitochondria.

GROUP II introns are present in the genomes of eubacteria and archaebacteria and in the organelle genomes of fungi and plants (Michel and Ferat 1995; Dai and Zimmerly 2002, 2003). Some of them, including all four present in yeast mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), can self-splice in vitro using a splicing mechanism resembling that of spliceosomal introns. Nearly all of the introns in organelle genomes interrupt genes, but a significant fraction of group II introns in bacteria are in intergenic regions (Dai and Zimmerly 2002).

Many group II introns contain an open reading frame that codes for a protein. It was first shown for the yeast introns aI1 and aI2 that the intron-encoded protein (IEP) has splicing (maturase), reverse transcriptase (RT), and endonuclease (endo) activities (Kennell et al. 1993; Zimmerly et al. 1995a,b; Yang et al. 1996; Eskes et al. 1997). The yeast introns carry out efficient mobility or “homing” (Dujon et al. 1989) in crosses between donor strains that have the intron and recipient strains that lack it. Homing by these introns employs all three functions of the IEP and depends on splicing. A number of other group II introns are now known to be mobile, including some in bacteria (Belfort et al. 2002).

The homing mechanism was first characterized for the yeast introns aI1 and aI2. The IEP accumulates in intron donor cells as ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particles together with the excised intron RNA lariat (Belfort et al. 2002). In mated cells, RNP particles first reverse splice the intron RNA into the sense strand of double-stranded mtDNA targets. Next, the endo activity cleaves the antisense strand downstream of the insertion site and then the RT uses the 3′OH end of the cleaved antisense strand as primer for first-strand cDNA synthesis. Initial research in yeast suggested that most retrohoming events involve synthesis of a partial cDNA followed by strand invasion of the intron in a donor genome, with completion of intron insertion by recombination (Eskes et al. 1997, 2000). The role of recombination in yeast intron homing was inferred by the finding that most retrohoming events occur with co-conversion of single nucleotide sequence tags in the exon upstream of the intron, but not downstream. The yeast introns retain 40–50% homing activity in crosses where the intron donor strain lacks RT activity (Moran et al. 1995; Eskes et al. 1997, 2000). Flanking marker analysis of RT-deficient crosses showed that bidirectional co-conversion of flanking markers is diagnostic of the RT-independent homing (Eskes et al. 1997, 2000).

Intron Ll.LtrB of Lactococcus lactis inserts in its target site with no flanking marker co-conversion (Cousineau et al. 1998). Its homing appears to depend on synthesis of full-length cDNA with completion by a repair process that is independent of general recombination. In the original aI2 crosses, such events are rare (Moran et al. 1995; Eskes et al. 2000), but later we found that several target-site mutations increase the efficiency of full reverse splicing and divert some retrohoming events to that pathway (Eskes et al. 2000). Although the bacterial introns appear to be limited to the recA-independent pathway, all three types of homing coexist in yeast mitochondria (Eskes et al. 2000). An intron of Sinorhizobium meliloti is mobile even though it lacks the conserved part of the endo domain (Martinez-Abarca et al. 2000). It is not yet clear how those events occur without the endo activity of the RT protein, but recent studies of the L. lactis intron identified a low level of endo-independent homing in which cDNA synthesis appears to be primed by a replication intermediate (Zhong and Lambowitz 2003).

Some years ago it was found that several fungal introns, including yeast aI1, transpose to ectopic sites in mtDNA (Muller et al. 1993; Sellem et al. 1993; Schmidt et al. 1994). Those ectopic sites resemble the natural homing site, so that the low frequency of such transpositions probably results from imperfections in the ectopic sites. aI1 RNP particles can reverse splice into DNA substrates containing any of the known transposition sites for that intron, although only at 0.5–3% of the extent of control reactions (Yang et al. 1998). We recently showed that DNA, rather than RNA, is the main or sole target for aI1 transposition (Dickson et al. 2001) and the same conclusion was reached for the L. lactis intron (Cousineau et al. 2000; Ichiyanagi et al. 2002).

Complex introns, called twintrons, were first found in the cpDNA of Euglena gracilis (Copertino and Hallick 1991). There, one intron is inserted within another in such a way that splicing of the internal intron reconstitutes the external intron so that it can splice. Several archaeal genomes contain “piles” of group II introns that resemble twintrons, with the exception that some of them are not functional introns (Dai and Zimmerly 2003). The inference that both twintrons and intron piles result from intron transposition suggests that intron transposition has influenced organelle and bacterial genome evolution.

Studies of aI1 transposition into the aI5β848 site in intron aI5β of the COXI gene yielded PCR evidence for both junctions of the expected product of inserting the entire aI1 into aI5β (Muller et al. 1993; Dickson et al. 2001). However, that mtDNA contains tandem copies of aI1 separated by 5.7 kb of COXI gene sequence and mitochondrial recombination efficiently excises one copy of the intron along with the sequence between the intron copies, so that stable strains with the twintron are not obtained. The aI1 intron in strains with the resulting deleted form of COXI splices well and is active for homing into E1/E2 sites (Eskes et al. 1997).

To focus on the immediate products of aI1 transposition, we developed a system in which transposition can occur in trans. An efficient E1/E2 target site was placed in aI5β of a recipient strain that lacks aI1 so that transposition is initiated by mating the engineered recipient strain to an intron donor strain that lacks an active target site in aI5β. Homing to the natural E1/E2 site in the recipient COXI gene is blocked by a mutation in E1 so that the only active site in the recipient genome is the ectopic one in aI5β. The engineered site proved to be a very active target in these crosses, but nearly all initiated events fail to insert the intron. Instead, most events abort and the cleaved target site is repaired by strand invasion of the aI5β present in the mtDNA of the intron donor strain. Our analysis of this system provides new insights to homing and transposition mechanisms of group II introns in yeast mitochondria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and genetic manipulations:

Yeast cultures were grown and analyzed genetically as described (Moran et al. 1995). Yeast mtDNA genotypes are denoted by a convention in which a superscript + indicates the presence of the wild-type intron, a superscript 0 indicates the absence of an intron, and other superscripts refer to specific mutations. The intron donor strain, 1+t20, is a derivative of strain ID41-6/161 (MATa ade1 lys1) and has the six-intron form of the COXI gene shown in Figure 1, line 1 (Moran et al. 1995; Eskes et al. 1997). In strain 1YAHH20, the RT activity is blocked by the YAHH mutation of the conserved YADD motif of the RT domain in strain 1+t20 (Eskes et al. 1997; Dickson et al. 2001). Strain C2107 has the 1+2Δ COXI deletion diagrammed in Figure 1, line 4 (Eskes et al. 1997). Strain 1+20 was constructed by homing the wild-type aI1 from C2107 into the COXI gene of strain Δ1Δ2 that lacks aI1 and aI2 but contains the other five COXI gene introns (Moran et al. 1992), followed by sporulation and cytoduction of the mtDNA into the nuclear background of strain ID41-6/161.

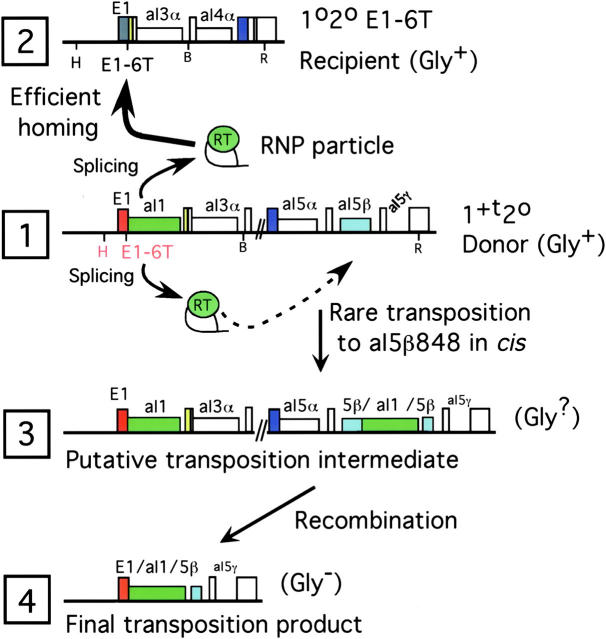

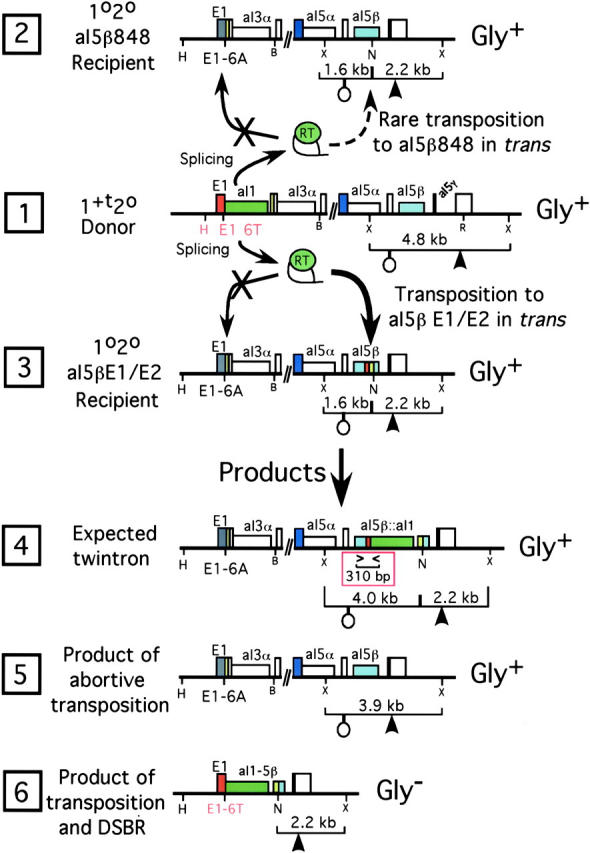

Figure 1.—

Diagrams of the standard aI1 donor and recipient COXI alleles, a putative intermediate and the main product of cis transposition. Exons and intron reading frames are tall and shorter rectangles, respectively. The 1+t20 donor and 1020 E1-6T recipient alleles (lines 1 and 2) differ in the number of introns and the presence or spacing of the key restriction enzyme sites (H, HpaII; B, BamHI; and R, EcoRI). Line 3 shows the structure of the putative twintron intermediate in cis transposition and line 4 shows the final product that results from recombination between the two intron copies in line 3. The respiratory ability (glycerol growth) of each strain is indicated. Before this study it was not known whether the intermediate would be Gly+ or Gly−. Exon 1 in the donor and recipient strains is colored differently to indicate that the exons differ at several nucleotides (Eskes et al. 1997, 2000); the nucleotide E1-6 is a T in these two strains but an inactive allele, E1-6A, is present in recipient strains in this study (see Figure 2).

The recipient strain for control homing crosses has E1-6T GII-0 mtDNA and the nuclear background of strain GRF18 (MATα leu2 his3; Moran et al. 1995). The 1020 recipient alleles are all derived from the mtDNA of strain E1-6A GII-0 in the GRF18 nuclear background (Figure 2, line 2; Moran et al. 1995). Exon positions are defined according to their location relative to the aI1 insertion site; for example, E1-6 is the sixth nucleotide upstream from the E1/E2 boundary. A derivative of that strain was made in which the introns 5α, 5β, and 5γ were inserted by homing of aI5α with associated co-conversion of the other two introns (Moran et al. 1992); then a Gly− derivative containing the G588A mutation of the joining sequence between domains 2 and 3 of aI5γ was made by mitochondrial transformation (Dickson et al. 2001). The recipient alleles of aI5β used in this study were made by recombination with transformed plasmids derived from pTZ5β848S5γo-COXII described previously (Dickson et al. 2001). Recipient strains were made with the aI5β848 target followed by an NheI site, with E1/E2 in the sense and antisense orientation replacing 5β848 and with hybrids between E1/E2 and 5β848.

Figure 2.—

COXI allele diagrams for the 1+t20 × aI5βE1/E2 cross. The donor COXI allele 1+t20 and recipient COXI alleles 1020 aI5β848 and 1020 aI5βE1/E2 are diagrammed in lines 1–3, respectively. The sequence of aI5β in the aI5β848 recipient strain (line 2) is the same as in the donor strain (line 1) except that an NheI site has been added 20 bp after the ectopic insertion site. The aI5βE1/E2 strain (line 3) contains 50 bp of E1/E2 sequence in aI5β that includes the aI1 homing site plus the NheI site that follows the 20 bp of E2. The sequence of the inserted E1/E2 is exactly the same as that of the natural E1 and E2 in the donor strain. Restriction sites that were assayed in DNA blots (Figure 3) are shown along with the lengths of the expected restriction fragments. Probes that hybridize to a sequence in the last exon (large arrow) or in exon 5β (open circle) were used as indicated. The recipient E1 sequence at the natural location has the E1-6A allele that blocks homing there (Eskes et al. 1997). Line 4 shows the expected twintron product of aI1 transposition into the ectopic target in the strain shown in line 3. The locations of PCR primers used to detect twintron products in mtDNA from this cross are indicated in the red box below line 4 (see Dickson et al. 2001). Line 5 shows the actual main product of transposition in this cross. Line 6 shows a retrodeletion that is a minor product of transposition. The respiratory phenotype of strains carrying each allele is indicated. X, XbaI; N, NheI; H, HpaII; B, BamHI; R, EcoRI.

These constructions are analogous to those described in Dickson et al. (2001) according to the following details. Plasmid pTZ5β848S5γo-COXII contains the 3′ end of the COXI gene, including the natural aI5β848 site flanked by BamHI and NheI sites. The aI5β848 site in that plasmid was replaced with oligonucleotides containing the E1-6T E1/E2 target site (Eskes et al. 1997) in both the sense and antisense orientations so as to inactivate the BamHI site but not the downstream NheI site. Each cassette contains from E1−30 through E2+20 and includes the minimal aI1 homing site defined earlier (nt E1−22 through E2+10; Yang et al. 1998). The hybrid target site E1/5β contains the 30 bp of E1 and the last 20 bp of the aI5β848 site while the 5β/E2 site contains the first 30 bp of the aI5β848 site and the 20 bp of E2. Each plasmid was transformed into the mitochondria of a ρo derivative of strain MCC109 (MATα ade2-101 ura3-52 kar1-1), mated with a Gly− strain with the nuclear background of strain MY375 (MATa ura3 his4 kar1-1) and the COXI allele E1−6A GII-0 5αβγG588A in its mtDNA. Gly+ recombinants were screened for the absence of aI5γ and the presence of the transformed target site that had been placed in aI5β (Butow et al. 1996). Each construction was confirmed by DNA sequencing and then placed in the nuclear background of strain GRF18 by cytoduction.

Transposition crosses were carried out at least in triplicate as described for homing crosses and analyzed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) procedures, basically as described (Moran et al. 1995). Two oligonucleotides were used to probe RFLP blots of mtDNA from haploid strains and crosses: E2 bottom, complementary to nt 39–60 of COXI exon 6 (large arrow in Figure 2); E5β, nt 9–38 of exon 5β (open circle in Figure 2). The input ratios of parental mtDNAs are measured by scoring HincII digests of these mtDNA preparations for different-sized alleles of the COB gene, hybridized with an oligonucleotide containing nt 553–579 of COB intron 4 (Moran et al. 1995; Eskes et al. 2000).

Calculations:

The measured fraction of recipient COB allele in each DNA sample provides the expected level of the recipient COXI allele if no transposition or homing occurs. If the COXI target site is attacked in a given cross and converted to another form, fewer progeny than expected will have the recipient COXI allele and one or more nonparental COXI alleles will be present. For example, if 50% of the progeny in a cross have the recipient COB allele, but only 10% of the progeny have the recipient COXI allele, then 80% of the recipient alleles were “lost” in the cross (i.e., changed to another allele). In this fashion, the percentage of abortive transposition or percentage of homing was calculated for each cross using the formula: % homing or % abortive transposition = [(COB-R − COXI-R)/COB-R] × 100 (see Table 1). In crosses using the RT-deficient donor strain, the level of abortive transposition was quite low and the difference between COB-R and COXI-R was not significant; because those crosses yielded some recombinant progeny, the percentage of abortive transposition was calculated on the basis of the level of recombinant alleles in the progeny of each cross, with a correction factor determined from the crosses with high levels of abortive transposition.

TABLE 1.

Summary of quantitative analysis of transposition and homing crosses

| Line | Donor × recipient | No. of trans crosses |

% recipient COB |

% recipient COXI |

% recombination COXI |

% abortive transposition |

% homing (× recipient strain 1020 E1-6T) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1+t20 × 5βE1/E2 | 4 | 49 | 17 | 18 | 65 | 79 |

| 2 | 1+t20 × 5βE1/E2 antisense | 5 | 52 | 26 | 13 | 50 | 79 |

| 3 | 1+20 × 5βE1/E2 | 4 | 34 | 4 | 16 | 88 | 91 |

| 4 | 1+20 × 5βE1/E2 antisense | 3 | 36 | 6.7 | 17 | 81 | 91 |

| 5 | 1YAHH20 × 5βE1/E2 | 4 | 53 | 45 | 2.1 | 7* | 46 |

| 6 | 1YAHH20 × 5βE1/E2 antisense | 3 | 57 | 51 | 2.7 | 9* | 46 |

| 7 | 1+t20 × E1/5β | 4 | 54 | 58 | <0.5 | <1.7 | 79 |

| 8 | 1+t20 × 5β/E2 | 4 | 47 | 53 | <0.5 | <1.9 | 79 |

| 9 | 1+t20 × 5β/5β | 3 | 53 | 50 | <0.5 | <1.7 | 79 |

Each replicate trans transposition cross, including the crosses shown in Figure 3, was analyzed by phosphorimager scanning to determine the fraction of recipient COB, recipient COXI, and recombinant COXI alleles. The average of the values is shown and those values were used to calculate the percentage of abortive transposition (as described in materials and methods). Standard deviations were calculated and for the first four crosses the differences between the percentage of recipient COB alleles and the percentage of recipient COXI alleles were highly significant. For transposition crosses using the 1YAHH20 (RT-deficient) donor strain, the difference between those values is barely significant; because every transposition cross with the RT-deficient donor strain yielded some recombinant progeny (e.g., Figure 3, lane 5), clearly above the level present in the negative control cross (line 9), the percentage of abortive transposition for those crosses (*) was calculated from the fraction of recombinant progeny as described in materials and methods. Homing crosses used the donor strains shown and recipient strain 1020 E1-6T; the percentage of homing was calculated as described in materials and methods.

Biochemical methods:

Minipreps of mtDNA were obtained as described (Adams et al. 1997) and Southern blot analysis was as described (Moran et al. 1995) using suitable probes. Colony blots to screen progeny of crosses were carried out as described (Blanc et al. 1978). To detect full intron insertions at the ectopic site in crosses we used the described PCR strategy that detects the junction between upstream sequences in aI5β and aI1 (see red box below line 4 of Figure 2 and Dickson et al. 2001), using 12.5 ng of mtDNA (or less as stated in Figure 4) and 24 cycles of amplification. Splicing of COXI transcripts in parental and twintron progeny strains was measured as described (Dickson et al. 2001).

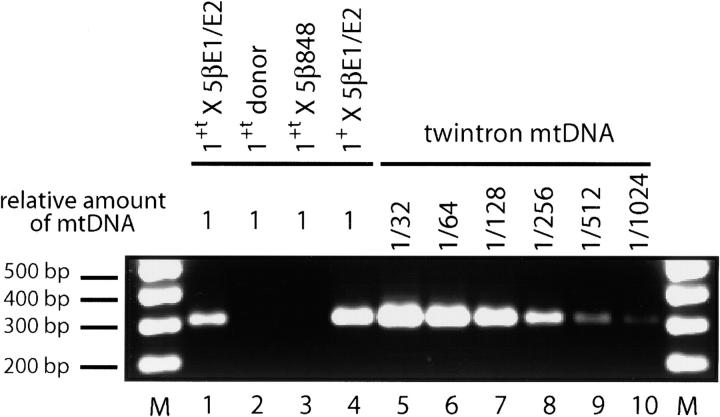

Figure 4.—

PCR analysis of twintron products of transposition. PCR reactions using primers defined in the red box below line 4 of Figure 2 and balanced amounts of mtDNA from the strains indicated above lanes 1–4 were carried out for 24 cycles and the products were fractionated on a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The reaction in lane 1 contains 12.5 ng of purified mtDNA based on A260. Reactions in lanes 2–4 contain an equivalent amount of mtDNA based on quantitated Southern blots for common COB gene sequences. The identity of the PCR product in lane 1 was confirmed by DNA sequencing. To estimate the level of twintrons formed in the crosses shown in lanes 1 and 4, PCR reactions were carried out with the indicated dilutions of a balanced sample of mtDNA from a diploid strain that has the twintron allele (lanes 5–10).

RESULTS

A trans assay for aI1 transposition in yeast mitochondria:

The parental COXI alleles present in the standard aI1 donor (1+t20) and recipient (1020 E1-6T) strains are diagrammed in Figure 1, lines 1 and 2. Those alleles were designed to have RFLP alleles both upstream (HpaII sites at different distances from the aI1 insertion site) and downstream (different numbers of introns altering the distance between the conserved BamHI and EcoRI sites). There are also single nucleotide differences in exons 1–3 (indicated by the different colors for exon 1 in Figure 1) that permit fine-structure analysis of homing events (Eskes et al. 1997). We found previously that nucleotide E1-6 of the recipient allele is crucial for aI1 homing: E1-6T supports homing while E1-6A weakens the EBS1/IBS1 pairing and blocks homing (Eskes et al. 1997). In haploid cells of the donor strain, aI1 transposes at low frequency to ectopic sites downstream in the COXI gene and our previous study focused on events at one site in aI5β, known as aI5β848 (Dickson et al. 2001). In this study we refer to such events as cis transpositions because no cross is needed to initiate such events. Previous research has proposed a putative intermediate in aI1 transposition that results from insertion of the entire intron within aI5β (Muller et al. 1993; Schmidt et al. 1994; Figure 1, line 3). Recombination then excises one copy of the intron and the middle of the COXI gene, resulting in the deletion shown in line 4.

To study aI1 transposition in crosses (i.e., in trans, because events are initiated by mating and there are distinct donor and recipient mtDNAs) we constructed a recipient strain in which the natural 5β848 site is replaced by an active homing site marked by an NheI site at its 3′ boundary (strain 1020 aI5βE1/E2, see Figure 2, line 3). That strain has the E1-6A allele in its natural E1 to block homing to that site, as indicated. For a negative control we also constructed recipient strain 1020 aI5β848 in which the aI5β848 site is marked with an NheI site (Figure 2, line 2).

Efficient abortive transposition:

Both recipient strains (Figure 2, lines 2 and 3) were mated to the aI1 donor strain 1+t20 (Figure 2, line 1) and the outcomes of the crosses were analyzed as Southern blots of XbaI+NheI digests (Figure 3) using an exon 5β probe (open circle in Figure 2). This analysis yields a unique restriction fragment for each parental allele (Figure 2, lines 1–3, and Figure 3, lanes 1 and 2) and for the predicted twintron product of full intron insertion (Figure 2, line 4; Figure 3, lane 12). The allele pattern in the negative control cross (Figure 3, lane 6) shows that the aI5β848 recipient allele does not support a level of transposition detectable by this RFLP assay. The 4.8-kb donor and 1.6-kb recipient alleles are present in the progeny in the expected proportion on the basis of transmission of alleles of the COB gene (Table 1, line 9; for details of the calculations, see materials and methods and Moran et al. 1995; Eskes et al. 2000).

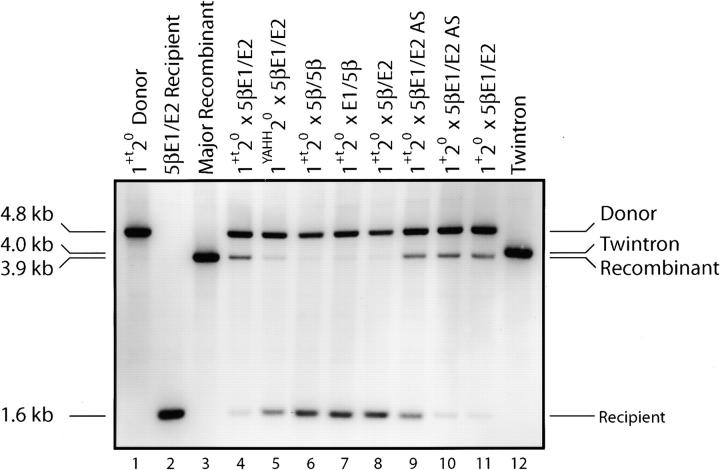

Figure 3.—

RFLP analysis of transposition in crosses. Crosses between the indicated donor and recipient strains were carried out as described in materials and methods and the outputs of COXI alleles were measured using the XbaI+NheI digest diagrammed in Figure 2, hybridized with the exon 5β probe (open circle in Figure 2). The same gel was hybridized with the exon 6 probe (arrowhead in Figure 2) and the results are discussed in the text. Lanes 1 and 2 show the 1+t20 and 1020 5βE1/E2 parental alleles and lane 4 shows the results of the cross between them. Lane 3 is DNA from a representative product of abortive transposition isolated from that cross (diagrammed in Figure 2, line 5). Lane 5 shows the result of a cross using an RT-deficient donor strain. Lanes 6–8 show results of crosses between the 1+t20 donor and recipient strains with the 5β848, E1/5β, and 5β/E2 targets, respectively. Lanes 9 and 10 show crosses using a recipient strain with the E1/E2 target inserted in aI5β in the inverse orientation and lane 11 shows the cross between donor strain 1+20 and recipient 5βE1/E2. The DNA samples for all of the crosses were also scored for the output of alleles of the COB gene (not shown; see materials and methods and Eskes et al. 1997). The percentage of progeny with the recipient COB allele was measured and used to calculate the extent of abortive transposition in each cross (summarized in Table 1).

The array of COXI alleles in progeny of the 1+t20 × aI5βE1/E2 cross (Figure 3, lane 4; Table 1, line 1) clearly differs from that of the negative control cross: there are significantly fewer progeny with the recipient allele than is predicted from the level of COB alleles (49% expected vs. 17% observed) and there is a prominent nonparental band at 3.9 kb (18% of progeny). That band does not hybridize with an aI1-specific probe, showing that it is not the expected 4.0-kb product of aI1 insertion into aI5β (see Figure 2, line 4). These findings show that the high-frequency events that occur in this cross do not insert aI1 into aI5β.

Over 95% of the progeny of this cross are Gly+ and screening easily yielded isolates that have the 3.9-kb nonparental allele. Detailed analysis of several isolates defines the allele diagrammed in Figure 2, line 5. A digest using mDNA from a representative is shown in Figure 3, lane 3. We conclude that those alleles are derivatives of the recipient COXI gene because they have upstream and downstream markers of the recipient allele (i.e., in these alleles the HpaII site is farther from exon 1 and they lack aI5γ). However, they also lack the NheI site that is a marker for the E1/E2 target in aI5β. Finally, we amplified and sequenced the relevant portion of the 3.9-kb XbaI fragment from two such recombinants, confirming that each contains the donor aI5β848 sequence and lacks aI5γ. These data show that this cross carries out efficient gene conversion of the E1/E2 insertion in the recipient aI5β, replacing it with the donor aI5β848 sequence. This outcome results from high frequency but incomplete (i.e., abortive) attempts to insert the intron in aI5β (see discussion).

Quantitation of the levels of progeny alleles in Figure 3, lane 4 (and replicate experiments summarized in Table 1, line 1) shows that attempted transposition results in loss of ∼65% of the recipient aI5βE1/E2 alleles. We noted that only ∼57% of the “lost” recipient alleles are recovered as 3.9-kb recombinant alleles. Further analysis of these allele patterns shows that there are more progeny with the donor allele than expected on the basis of the level of donor COB alleles in these DNA samples: we expected 51% of the progeny to have the 4.8-kb donor COXI allele, but instead found 65%. This excess of donor alleles likely results from events in which gapping before strand invasion extends into exon 6. In that case strand invasion occurs in exon 6 of the donor genome, rather than in aI5β, so that aI5γ is co-converted along with the donor aI5β sequence (see discussion). Importantly, in the negative control cross (Figure 3, lane 6, and Table 1, line 9) the level of progeny COXI alleles matches the level predicted on the basis of progeny COB alleles, within experimental error.

A low level of retrotransposition occurs in trans:

Further analysis shows that the 1+t20 × 5βE1/E2 cross carries out a low level of retrotransposition, yielding two different products. The PCR assay diagrammed in the red box below line 4 of Figure 2 readily detects in mtDNA from the donor 1+t20 strain a low level of the aI5β-aI1 junction that is diagnostic of the twintron putative intermediate in cis transposition (Dickson et al. 2001). Using balanced amounts of mtDNA and 24 cycles of amplification, we obtained a strong signal with mtDNA from the 1+t20 × 5βE1/E2 cross (Figure 4, lane 1) and no signal with mtDNA from the haploid strain 1+t20 (lane 2) or from the 1+t20 × 5β848 cross (lane 3). For the latter two samples, the same PCR product is obtained if more cycles are used (not shown; see Dickson et al. 2001).

Screening of 440 progeny of the 1+t20 × 5βE1/E2 cross yielded one twintron strain. Characterization of that allele (not shown, but see Figure 3, lane 12) confirmed the details of the allele diagram shown in Figure 2, line 4. The strain is Gly+ and splices the twintron as well as the donor or recipient strain splices aI5β (not shown). Using mtDNA from the twintron strain to calibrate the level of full intron insertions, we found that ∼0.4% of the progeny of the 1+t20 × 5βE1/E2 cross are twintrons (Figure 4, compare lane 1 with lanes 5–10). Because twintrons formed by cis transposition account for ∼0.003% of the mtDNA from the haploid 1+t20 strain (Dickson et al. 2001), these data show that presence of the E1/E2 target site in aI5β elevates the level of full intron insertions at least 133-fold (0.4/0.003).

Most aI1 retrohoming events result from partial cDNA synthesis followed by recombination (Eskes et al. 1997), so it is likely that a partial cDNA is made in many trans events. Because there is so little full intron insertion in the trans cross, events with partial cDNAs probably abort by gapping followed by gene conversion of aI5β. Alternatively, some partial cDNAs may invade aI1 in donor mtDNA and such events would result in COXI deletions like those formed by cis transposition (Figure 1, line 4), although without first inserting the complete intron. About 2% of the progeny of the 1+t20 × 5βE1/E2 cross are Gly− and screening a sample of those progeny identified eight strains with the predicted COXI deletion. Southern blot analysis showed that those progeny are derived from the recipient gene because each lacks aI5γ. Because they contain the NheI site that marks the inserted E1/E2 site (see Figure 2, line 6), those events occurred without downstream co-conversion. We conclude that they resulted from retrotransposition and refer to them as “retrodeletions” (see discussion). Two of the eight retrodeletions were co-converted for the upstream E1-387 HpaII site, consistent with our previous finding of ∼20% co-conversion of that site in aI1 and aI2 homing crosses (Eskes et al. 1997, 2000). These retrodeletions would not be evident on the blot shown in Figure 3, but are observed as a faint signal in HpaII digests of the 1+t20 × 5βE1/E2 cross hybridized with an exon 1 probe; that signal is absent from the negative control cross (not shown).

Donor and target-site requirements of abortive transposition:

Homing by this aI1 allele at the natural E1/E2 site is inhibited ∼58% by the YAHH mutation of the YADD motif of the RT domain (Eskes et al. 1997) and that mutation blocks detectable cis transposition of aI1 to the aI5β848 ectopic site (Dickson et al. 2001). The 1YAHH20 × aI5βE1/E2 cross is shown in Figure 3, lane 5, and, as summarized in Table 1, line 5, the level of abortive transposition is inhibited ∼88%. These data indicate that efficient abortive homing is more dependent on the RT activity than is homing (see discussion).

We lack a tight endo-domain mutant of aI1 that retains RT activity so we have not directly determined the dependence of abortive transposition on endo activity. The 1+t20 donor allele has a mutation of a nonconserved amino acid in the En domain (T744L), relative to its parent strain (1+2+) (Kennell et al. 1993). Previous biochemical experiments establish that RNP particles from strain 1+t20 have a partial defect in endo and target DNA-primed reverse transcription (TPRT) activities relative to RNP particles from a strain with wild-type aI1 (using strain 1+2Δ; see Figure 1, line 4), although reverse splicing activity was not evidently affected (Yang et al. 1998). To test whether T744L might be a significant factor leading to abortive transposition in this study, we constructed a new donor strain (1+20) in which the T744L mutation had been repaired. As shown in Table 1, lines 1 and 3, strain 1+20 is more active in homing crosses than is strain 1+t20 (91% homing vs. 79%). As shown in Figure 3, lane 11 (and Table 1), strain 1+20 is more active in trans transposition crosses than is strain 1+t20 (88% loss of recipient alleles vs. 65%); however, the only evident nonparental allele in those crosses is the 3.9-kb band that results from abortive transposition. The increased level of abortive transposition may result from the increased input of donor mtDNAs in the 1+20 cross, rather than from inherently more efficient RNP particles. Using PCR, we detected ∼0.8% twintron progeny in the 1+20 × 5βE1/E2 cross (Figure 4, lane 4) and that finding was confirmed by the presence of a faint signal at 4.0 kb in blots of XhaI+NheI digests of those DNA samples hybridized with an aI1 probe (not shown). These data show that the T744L endo-domain mutation may partially inhibit the extent of homing and abortive transposition, but is not responsible for the striking inefficiency of retroevents in this system.

Next we tested the extent to which abortive transposition depends on elements of the E1/E2 target site. Derivatives of the 5βE1/E2 target site in which the E1/E2 insertion was replaced by sequences intermediate between the E1/E2 and 5β848 sites were made. Strain 5β/E2 contains the first 30 bp of the 5β848 site followed by the first 20 bp of E2 and strain E1/5β has the reciprocal site, containing the last 30 bp of E1 followed by the downstream 20 bp of the 5β848 site. We already showed in Figure 3, lane 6, that the 5β848 recipient strain has essentially no abortive transposition in this assay. Each hybrid recipient strain was mated to the 1+t20 donor strain and the outcome of each cross was determined by RFLP analysis. As shown in Figure 3, lanes 7 and 8, neither hybrid site supports a significant level of abortive transposition. In those gel lanes there is a faint 3.9-kb signal that represents <0.5% of the progeny and there is no significant loss of recipient alleles in those crosses (Table 1, lines 7 and 8). These data show that efficient abortive events depend on the E1 sequences of the target site, presumably for efficient reverse splicing, and on the E2 sequences of the target site, presumably for efficient endo cleavage. In contrast, inverting the E1/E2 site in aI5β permits a high level of abortive transposition in crosses with the 1+t20 and 1+20 donor strains (Figure 3, lanes 9 and 10, and Table 1, lines 2 and 4) with 77 and 92% of the levels observed with the E1/E2 site in the sense orientation, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study of transposition of the group II intron aI1 to a homing site placed ectopically in the group I intron aI5β resulted in several unexpected findings that provide new insights into mechanisms of group II intron mobility in yeast mitochondria. It was found that the ectopic E1/E2 site is readily attacked by the mobile aI1 and three different outcomes were characterized. Although the 1+t donor intron inserts successfully at ∼80% of E1-6T recipient sites in standard homing crosses (Eskes et al. 1997), abortive events affect ∼65% of recipient alleles in this trans transposition system. About 2% of target sites are converted to retrodeletions and the least-frequent events are the <1% retrotranspositions in which the E1/E2 target is split by insertion of the complete aI1. The aI1 RT function is more important for abortive transposition than for homing, suggesting that initial cDNA synthesis promotes those events (see below). The requirement for E1 sequences suggests that reverse splicing is important for abortive transposition. The findings that E2 sequences are needed for high levels of abortive events and that a missense mutation that partially inhibits the endo activity lowers the level of abortive transposition suggest that endo cleavage is important.

In our previous study of cis transposition we characterized an inverted 5β848 site and our finding that the inverted site remains active for transposition helped demonstrate that DNA sites are the targets in most or all such events (Dickson et al. 2001). Here, we analyzed an inverted E1/E2 site in aI5β and found that it is only slightly less active for abortive transposition than is the E1/E2 site in the sense orientation (Figure 3, lanes 9 and 10, and Table 1). Transposition in a bacterial system exhibits a strand preference that reflects a role for the lagging strand of DNA replication (Ichiyanagi et al. 2002) that is also exhibited by endo-independent homing by that intron (Zhong and Lambowitz 2003).

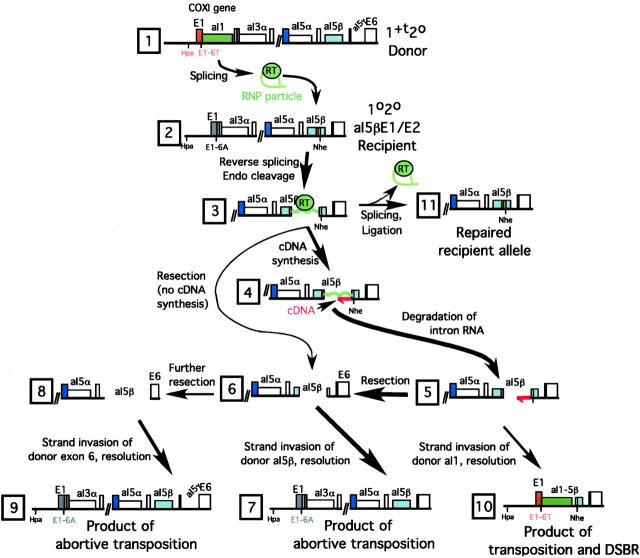

Figure 5 summarizes our thinking about how those insertion, deletion, and abortive events occur. We know from previous in vitro experiments that RNP particles from the 1+t20 donor strain are active for reverse splicing, antisense-strand cleavage, and cDNA synthesis by TPRT at the E1-6T E1/E2 target site (Yang et al. 1996, 1998; Eskes et al. 1997), so it was expected that the 5βE1/E2 site would be attacked efficiently in vivo by aI1 RNP particles. The transposition intermediate shown in Figure 5, line 3, is likely formed at high frequency in this cross. cDNA synthesis should be initiated at most such targets (line 4), although it was surprising that so many of the initiated events abort from intron insertion. This appears to entail removal of the intron RNA from the intermediate and resection of any initial cDNA plus the ectopic E1/E2 target site (lines 5 and 6). Single strands then invade intact aI5β in donor mtDNA, resulting in repair of the resected recipient allele, converting it to the donor aI5β allele (line 7).

Figure 5.—

Pathways for aI1 transposition. The diagram summarizes features of aI1 transposition demonstrated or inferred in this study (see also Figures 2 and 3). Line 1 shows the donor COXI allele 1+t20. Line 2 shows the recipient COXI allele aI5βE1/E2. Line 3 shows the initial retrotransposition intermediate formed by reverse splicing and antisense-strand cleavage at the ectopic E1/E2 target. It is a key intermediate that can be further processed in at least the three different ways indicated (from line 3 to line 4 or to line 6 or to line 11). Line 4 shows the intermediate in which an initial cDNA has been primed by the cleaved antisense strand of the target site. Line 5 shows a later intermediate in which the inserted intron RNA has been degraded; although the diagram shows the complete removal of the RNA, the most important aspect of this step is removal of the RNA complement of the cDNA. Line 6 shows the site after resection to remove the short cDNA and portions of aI5β flanking the cleaved target site; resection of both strands is likely but to progress to the next step it is likely that ends with 3′-ended single strands are formed. Some of the evidence suggests that some of the line 3 intermediate progresses directly to the one shown in line 6 by degradation of the inserted intron RNA. Line 7 illustrates the main product of abortive transposition formed from the intermediate shown in line 6 by strand invasion of aI5β sequences in a donor mtDNA (as in line 1). In some instances resection of the cleaved target extends into exon 6 (line 8) and that intermediate can invade the donor mtDNA, resulting in the repaired product shown in line 9. The intermediate in line 5 can invade aI1 sequences in a donor mtDNA with completion by recombination forming the deleted product of transposition shown in line 10. As developed in the text, the intermediate in line 3 may be repaired directly back to its original state by ejecting the inserted intron RNA by forward splicing, followed by ligation of the antisense strand (line 11).

The 5βE1/E2 site is located 668 bp from the 3′ end of aI5β. Because abortive products that lack aI5γ (Figure 5, line 7) are a significant product of this cross (Figure 3, lane 4), we conclude that gapping before strand invasion is often less extensive than 668 bp. Because the exon that follows aI5β is only 25 bp long, resection of >693 bp would cross into E6; in that case, strand invasion would occur in E6 and aI5γ would be copied into the repaired COXI gene (Figure 5, lines 8 and 9). That product would be indistinguishable from the donor allele in the blot shown in Figure 3. In the negative control (1+t20 × 5β848), the levels of donor and recipient COXI alleles closely match the expectation based on the levels of the donor and recipient COB alleles (Table 1, line 9). However, in every cross where abortive transposition was evident, the fraction of progeny with the donor allele was, in fact, elevated. In the 1+t20 and 1+20 crosses, 55% of the lost recipient alleles were recovered as the 3.9-kb recombinant and most of the rest were accounted for as excess donor alleles. These data indicate that gapping of >693 bp occurs ∼45% of the time.

The residual abortive transposition in the cross that lacks RT activity shows that cDNA synthesis is not essential for this outcome; that is, genomes can proceed from the reverse spliced and endo-cleaved target site (Figure 5, line 3) directly to the resected intermediate (line 6). However, the RT mutation inhibits abortive homing significantly more than it inhibits homing (see Table 1). That result suggests that cDNA synthesis actually promotes abortive events. RNP particles from the 1YAHH20 donor strain have ∼50% of the control level of endo activity (Eskes et al. 1997; and presumably at least that level of reverse-splicing activity), so it is unlikely that abortive events are limited by the levels of those activities. We infer that initial cDNA synthesis, which should be as efficient in the trans cross as in the homing cross (where ∼58% RT-independent homing occurs; Eskes et al. 1997), traps the intron RNA in the cleaved DNA target. Even so, we conclude that initial cDNA synthesis in this trans system does not commit more than a small fraction of events to retrotransposition; instead, the initial cDNA is often removed by gapping en route to the abortive outcome (see Figure 5, lines 5 and 6).

Most of the intermediates of Figure 5, lines 4 and 5, appear to be resected into aI5β sequences, as indicated in Figure 5, line 6. However, a minority of cDNAs either are longer or otherwise survive long enough to invade aI1 in a donor mtDNA so that the deletion shown in line 10 is formed. Because these deletions are not co-converted downstream of the intron insertion site, we conclude that they are products of retrotransposition. Full intron insertion occurs in this context at a lower level than that of these retrodeletions. The rarity of those events here shows that the pathway from line 5 directly to line 10 is somewhat more effective than the alternative pathway of inserting the entire intron into aI5β via a full-length cDNA.

These findings provide new insights to several aspects of cis transposition and homing in this system. Previous studies suggested that the twintron is a key intermediate in cis transposition of aI1, en route to retrodeletions (see Figure 1; Muller et al. 1993; Dickson et al. 2001). In the trans system the retrodeletion cannot pass through the twintron intermediate (see Figure 1, line 3), yet it occurs >100 times more frequently than in the cis case. This finding makes is unlikely that aI1 usually passes through the twintron intermediate in the cis configuration. Instead, most cis events probably involve partial cDNA synthesis and invasion of the upstream aI1, resulting in the retrodeletion directly.

In these trans crosses in which no cDNA is made or resection removes the initial cDNA, gene conversion of the recipient aI5β to the donor aI5β occurs. In homing crosses, initial cDNAs of intron sequence invade the intron in a donor mtDNA and recombination completes the intron insertion in the recipient genome with upstream co-conversion. In homing crosses, RT-independent events entail resection of the cleaved target site so that strand invasion of a donor mtDNA inserts the intron with co-conversion both upstream and downstream. In both situations the intron is inserted because it is present in a large fraction of the intact mtDNAs that are available as targets for strand invasion after most recipient genomes have been cleaved by reverse splicing. When these aspects of homing crosses are described this way, it is evident that abortive transposition and RT-independent homing are rather similar mechanistically, even though only the latter regularly succeeds in inserting the intron.

Because abortive events occur more frequently when the RT is active, we infer that some events may abort even earlier in the pathway when no cDNA is made (Figure 5, line 11). We suggest that some intermediates shown in line 3 may eject the inserted intron RNA from the DNA target by forward splicing; the remaining nick in the antisense strand should be easily repaired, restoring the original recipient allele. This can be thought of as an “idling” pathway. Such idling may also occur in homing crosses, perhaps accounting for some of the ∼10–15% of recipient alleles that do not acquire the intron in crosses. Synthesis of even a short cDNA would unfold the domain 6 intron structure and lock the intron RNA into the DNA target, thus promoting homing or transposition, including abortive outcomes. Recent kinetic analysis of reactions of L. lactis RNP particles with DNA target substrates emphasized the improbability of reverse splicing and suggested the importance of trapping the reverse-spliced intermediate (Aizawa et al. 2003).

In vitro experiments with aI1 RNP particles have revealed several lines of evidence for such an idling reaction. For example, mutating the δ′ nucleotide (E2 + 1) strongly inhibits accumulation of products of aI1 reverse splicing but not products of antisense-strand cleavage (Guo et al. 1997). Also, a product of TPRT reactions in which the sense strand was intact but a short cDNA had been made at the antisense-strand nick has been described (Yang et al. 1998). Both of those findings can be explained by this idling reaction in which reverse-spliced intron RNA is ejected from a homing intermediate after the antisense strand has been cleaved. Because the 1+t allele has less endo activity than the 1+ allele (Yang et al. 1998), this idling reaction may also account for the lower level of abortive transposition in crosses using the 1+t donor strain.

Although cis transposition of aI1 occurs at the aI5β848 site at a frequency of 0.003% (Dickson et al. 2001), that site is active for reverse splicing at 1–3% of the activity using the standard E1/E2 substrate (Yang et al. 1998). Thus, reverse splicing probably occurs more frequently than the observed transposition-associated deletions at the aI5β848 site in vivo. The aI5β848 site is, at best, a poor substrate for antisense-strand cleavage in vitro, so it is likely that reverse-spliced molecules are substantially repaired by the idling reaction inferred above. No antisense-strand cleavage was detected in vitro using any of the cis ectopic site substrates and that leaves unresolved how cis retrotransposition occurs there at all. RT activity leading to the rare but successful retrotranspositions may be primed by other mtDNA transactions, for example, leading-strand DNA replication intermediates or nicks formed by another endonuclease. Our analysis of these trans crosses, however, suggests that even when the antisense strand is cleaved and an initial cDNA is made, most events abort and are repaired by gene conversion with another mtDNA.

It is rather surprising that this mobile intron has so many ways of completing events in yeast mitochondria, including the abortive pathways detected in this study that convert an active site to a less active one or restore the original target site (Figure 5, lines 7–9 and 11, respectively). Approximately 20 copies of mtDNA are in a haploid yeast cell and at least that many of each parental type in a newly mated diploid zygote. Homing and trans transpositions are initiated in newly mated zygotes and there is a limited window of time for interactions involving both mtDNAs (and the probably more numerous and more diffusible RNP particles) before mtDNA segregation separates the different mitochondrial genomes in progeny cells. Given the moderate copy number of mtDNA, some events could simply fail and not be repaired, resulting in loss of the cleaved genomes. Yet, the diverse repair processes in mitochondria appear to be so robust that most or all initiated events are repaired. In the extreme case of these trans transposition crosses, there is a lot of activity at the target sites, but hardly any of that results in intron insertion.

In bacterial systems, where group II intron homing is often studied using multicopy plasmids and high-level expression of the intron-encoded protein, the overall frequency of successful events (i.e., the fraction of recipient plasmids that acquire the intron) is lower. In part, that may reflect the relative instability of the excised intron RNA in bacteria. However, as we have now shown for the yeast case, there may be more attempts at homing or transposition in bacterial systems than is apparent from the frequency of successful events. Because the sorts of gene conversions that we see in yeast mitochondria are relatively inefficient in bacteria (Clyman and Belfort 1992), some initiated events in bacteria may be unsuccessful and abort. Many events may stall after either reverse splicing or antisense-strand cleavage, in which case the forward-splicing idling process inferred to occur in yeast would repair those plasmids. Alternatively, some abortive events could result in loss of the invaded plasmid, something that does not appear to happen much, if at all, in the yeast system.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant GM-31480 from the National Institutes of Health and grant I-1211 from the Robert A. Welch Foundation.

References

- Adams, A., D. E. Gottschling, C. A. Kaiser and T. Stearns, 1997 Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Aizawa, Y., Q. Xiang, A. M. Lambowitz and A. M. Pyle, 2003. The pathway for DNA recognition and RNA integration by a group II intron retrotransposon. Mol. Cell 11: 795–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfort, M., V. Derbyshire, M. M. Parker, B. Cousineau and A. M. Lambowitz, 2002 Mobile introns: pathways and proteins, pp. 761–783 in Mobile DNA II, edited by N. L. Craig, R. Craigie, M. Gellert and A. M. Lambowitz. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- Blanc, H., B. Dujon, M. Guerineau and P. P. Slonimski, 1978. Detection of specific DNA sequences in yeast by colony hybridization. Mol. Gen. Genet. 161: 311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butow, R. A., R. M. Henke, J. V. Moran, S. C. Belcher and P. S. Perlman, 1996 Transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria using the biolistic gun, pp. 265–278 in Methods in Enzymology, edited by G. Attardi and A. Chomyn. Academic Press, San Diego/New York/Boston. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Clyman, J., and M. Belfort, 1992. Trans and cis requirements for intron mobility in a prokaryotic system. Gene Dev. 6: 1269–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copertino, D. W., and R. B. Hallick, 1991. Group II twintron: an intron within an intron in a chloroplast cytochrome b-559 gene. EMBO J. 10: 433–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau, B., D. Smith, S. Lawrence-Cavanagh, J. E. Mueller, J. Yang et al., 1998. Retrohoming of a bacterial group II intron: mobility via complete reverse splicing, independent of homologous DNA recombination. Cell 94: 451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau, B., S. Lawrence, D. Smith and M. Belfort, 2000. Retrotransposition of a bacterial group II intron. Nature 404: 1018–1021 (erratum: Nature 414: 1084). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L., and S. Zimmerly, 2002. Compilation and analysis of group II intron insertions in bacterial genomes: evidence for retroelement behavior. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 1091–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L., and S. Zimmerly, 2003. ORF-less and reverse-transcriptase-encoding group II introns in archaebacteria, with a pattern of homing into related group II intron ORFs. RNA 9: 14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, L., H.-R. Huang, L. Liu, M. Matsuura, A. M. Lambowitz et al., 2001. Retrotransposition of a yeast group II intron occurs by reverse splicing directly into ectopic DNA sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 13207–13212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujon, B., M. Belfort, R. A. Butow, C. Jacq, C. Lemieux et al., 1989. Mobile introns: definition of terms and recommended nomenclature. Gene 82: 115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskes, R., J. Yang, A. M. Lambowitz and P. S. Perlman, 1997. Mobility of yeast mitochondrial group II introns: engineering a new site specificity and retrohoming via full reverse splicing. Cell 88: 865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskes, R., L. Liu, H. Ma, M. Y. Chao, L. Dickson et al., 2000. Multiple homing pathways used by yeast mitochondrial group II introns. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 8432–8446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H., S. Zimmerly, P. S. Perlman and A. M. Lambowitz, 1997. Group II intron endonucleases use both RNA and protein subunits for recognition of specific sequences in double-stranded DNA. EMBO J. 16: 6835–6848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiyanagi, K., A. Beauregard, S. Lawrence, D. Smith, B. Cousineau et al., 2002. Retrotransposition of the Ll.ltrB group II intron proceeds predominantly via reverse splicing into DNA targets. Mol. Microbiol. 46: 1259–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennell, J. C., J. V. Moran, P. S. Perlman, R. A. Butow and A. M. Lambowitz, 1993. Reverse transcriptase activity associated with maturase-encoding group II introns in yeast mitochondria. Cell 73: 133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Abarca, F., F. M. Garcia-Rodriguez and N. Toro, 2000. Homing of a bacterial group II intron with an intron-encoded protein lacking a recognizable endonuclease domain. Mol. Microbiol. 35: 1405–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel, F., and J. L. Ferat, 1995. Structure and activities of group II introns. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64: 435–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, J. V., C. M. Wernette, K. L. Mecklenburg, R. A. Butow and P. S. Perlman, 1992. Intron 5α of the COXI gene of yeast mitochondrial DNA is a mobile group I intron. Nucleic Acids Res. 20: 4069–4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, J. M., S. Zimmerly, R. Eskes, J. C. Kennell, A. M. Lambowitz et al., 1995. Mobile group II introns of yeast mitochondrial DNA are novel site-specific retroelements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 2828–2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, M. W., M. Allmaier, R. Eskes and R. J. Schweyen, 1993. Transposition of group II intron aI1 in yeast and invasion of mitochondrial genes at new locations. Nature 366: 174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, W. M., R. J. Schweyen, K. Wolf and M. W. Mueller, 1994. Transposable group II introns in fission and budding yeast. Site-specific genomic instabilities and formation of group II IVS plDNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 243: 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellem, C. H., G. Lecellier and L. Belcour, 1993. Transposition of a group II intron. Nature 366: 176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., S. Zimmerly, P. S. Perlman and A. M. Lambowitz, 1996. Efficient integration of an intron RNA into double-stranded DNA by reverse splicing. Nature 381: 332–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., G. Mohr, P. S. Perlman and A. M. Lambowitz, 1998. Group II intron mobility in yeast mitochondria: target DNA primed reverse transcription activity of aI1 and reverse splicing into DNA transposition sites in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 282: 505–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J., and A. M. Lambowitz, 2003. Group II intron mobility using nascent strands at DNA replication forks to prime reverse transcription. EMBO J. 22: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerly, S., H. Guo, R. Eskes, J. Yang, P. S. Perlman et al., 1995. a A group II intron RNA is a catalytic component of a DNA endonuclease involved in intron mobility. Cell 83: 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerly, S., H. Guo, P. S. Perlman and A. M. Lambowitz, 1995. b Group II intron mobility occurs by target DNA-primed reverse transcription. Cell 82: 545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]