Abstract

The medical community has orchestrated breastfeeding campaigns in response to low breastfeeding rates twice in US history. The first campaigns occurred in the early 20th century after reformers linked diarrhea, which caused the majority of infant deaths, to the use of cows’ milk as an infant food.

Today, given studies showing that numerous diseases and conditions can be prevented or limited in severity by prolonged breastfeeding, a practice shunned by most American mothers, the medical community is again inaugurating efforts to endorse breastfeeding as a preventive health measure.

This article describes infant feeding practices and resulting public health campaigns in the early 20th and 21st centuries and finds lessons in the original campaigns for the promoters of breastfeeding today.

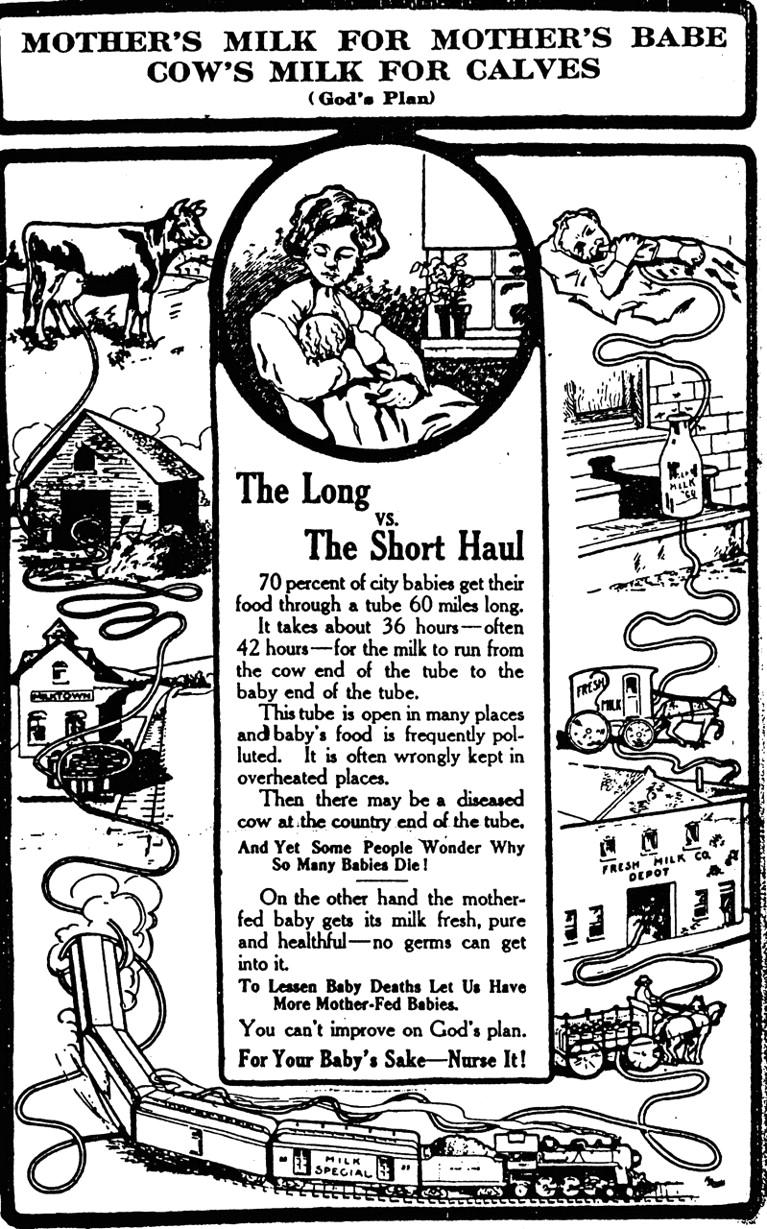

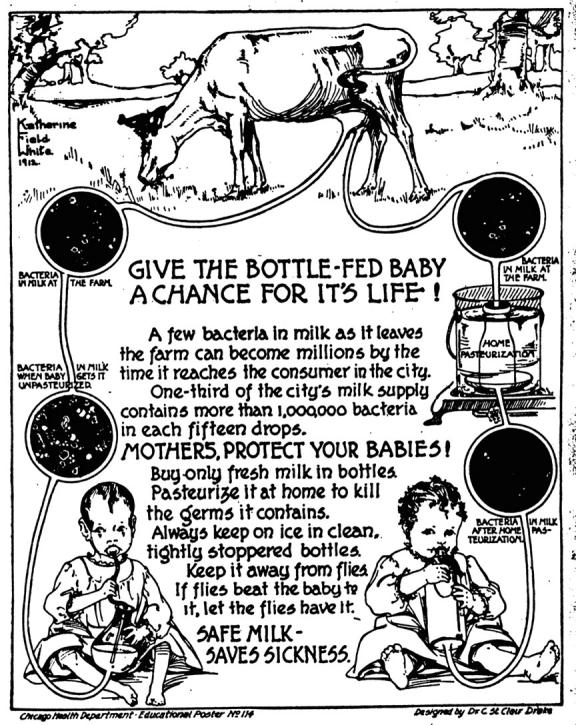

IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY, as part of the national campaign to lower infant mortality, public health officials around the country hung posters in urban neighborhoods urging mothers to breastfeed or to avoid feeding their babies the spoiled, adulterated cows’ milk that pervaded US cities. The language on the posters was unambiguous. One commanded, “To lessen baby deaths let us have more mother-fed babies. You can’t improve on God’s plan. For your baby’s sake—nurse it!”1 Another, which explained the importance of home pasteurization and keeping cows’ milk on ice if a mother did not breastfeed, pleaded, “Give the Bottle-Fed Baby a Chance For Its Life!”1

Figure 1.

Far left: A Chicago Infant Welfare Society nurse talks with mothers of infants in 1911. Photo courtesy of Chicago Historical Society.

By the late 1920s, with laws in most municipalities mandating the pasteurization and hygienic handling of cows’ milk, the urban breastfeeding campaign disappeared. Although low breastfeeding rates continued to generate public health problems, the link between human milk and human health was less obvious. Only recently has this relationship become evident again as contemporary research demonstrates that exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and prolonged breastfeeding thereafter is key to maintaining children’s and women’s health. Extended breastfeeding not only reduces the incidence in children of acute illnesses such as diarrhea, ear infections, pneumonia, and meningitis, it lessens the occurrence of chronic diseases and conditions such as sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), obesity, childhood leukemia, asthma, and lowered IQ. And women who practice prolonged breastfeeding enjoy significantly reduced rates of breast cancer. These studies have spurred renewed interest in publicizing the importance of breastfeeding.

With breastfeeding campaigns on the horizon after a century-long hiatus, the original crusades are worth examining. The old campaigns can teach the architects of breastfeeding promotions today that, as important as breastfeeding is to health, cultural norms often override healthy activities. If breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and duration rates are to increase in the United States, breastfeeding mothers need unambiguous medical, social, and cultural support.

CHANGE IN INFANT FEEDING PRACTICE

In the 1880s, women began in large numbers to supplement their own milk with cows’ milk shortly after giving birth and to wean their babies from the breast before they were 3 months old. This represented a stark change from the colonial era, when mothers normally breastfed at least through infants’ second summer.3 The move to early weaning was so relentless that doctors complained bitterly in a 1912 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association that breastfeeding duration rates had been declining steadily since the mid-19th century “and now it is largely a question as to whether the mother will nurse her baby at all.”4

Middle-class mothers corroborated this observation. They often referred in letters and diaries to “feeding” their babies, a shortened version of the term “hand-feeding,” meaning offering something other than the breast, usually cows’ milk, to an infant. One mother demonstrated just how commonplace hand-feeding was becoming when she wrote nonchalantly of her 3-month-old in 1884, “I feed her a little now.”5 Another mother explained to the readers of Babyhood magazine in 1887, “We have just welcomed our sixth baby, and, as our babies need to be fed after the third month, we are feeding this baby after the second week from its birth.”6 Josephine Laflin, a wealthy Chicago mother, reported in her diary in 1903 that she “decided to feed” her 10-week-old.7

This custom of “feeding” cows’ milk to tiny infants was not limited to women of means, however. Upper-, middle-, and working-class women alike—albeit prompted by different social, economic, and cultural factors—all participated in this practice.8 Upper-class women customarily turned their babies over to servants, precluding breastfeeding. As one typical wealthy father explained in 1893, nurses had cared for all 4 of his children, hence his wife “knew nothing about feeding them.”9 New expectations for marriage, based less on economics and procreation and more on love and companionship, influenced middle-class women’s infant feeding practices as their connection with their husbands began to eclipse their relationship with their infants. As one woman wrote to a magazine on behalf of her pregnant daughter in 1886, “She wants to be more of a companion for her husband than she could be if she should nurse Baby; and . . . we wonder if it would not be best for all that the little one be fed.”10

Economic factors were the primary force behind the infant feeding habits of working-class mothers. Women who worked outside the home had no choice but to leave their infants with grade-school daughters and artificial food.11 Samuel Preston and Michael Haines offer as evidence of this phenomenon statistics from late-19th-century Baltimore, where the mortality rate was 59% higher than average among infants whose mothers worked outside the home and 5% lower than average among babies whose mothers worked at home—taking in laundry and cooking meals for unmarried men, for example. Preston and Haines contend the likely reason for this difference in mortality is that stay-at-home working mothers breastfed.12 The disparity corroborates other studies conducted at the time that indicated that babies fed cows’ milk died at much higher rates than breastfed babies.13

INFANT FEEDING AND INFANT HEALTH

Although the reasons for cows’ milk feeding differed significantly according to class, the move to cows’ milk negatively affected the health of all infants. Consequently, physicians unanimously decried the “trouble and dangers of artificial feeding.”14 The Ladies’ Home Journal admonished mothers in 1900, “Cow’s milk is the food of the calf. . . . It is the violation of these laws of Nature which produces the so-called ‘cholera infantum’ [infant diarrhea] and the other diseases of the second summer.”15 Mothers of means customarily alleviated the ramifications of artificial feeding by hiring a wet nurse to rescue their sick babies. Working-class mothers, however, could not afford that luxury, and the results were obvious.16 In Chicago in the summer of 1909, public health workers identified the location of every infant death from diarrhea, and the resulting map indicated that infants living in congested immigrant neighborhoods died at much higher rates from the disease than babies living in wealthier neighborhoods.17

Chicago’s infant mortality statistics typified the nationwide crisis. In 1897, 18% of Chicago’s babies died before their first birthday and more than 53% of the dead died of diarrhea.18 The Chicago Department of Health estimated that 15 hand-fed babies were dying for every 1 breastfed baby.19 One exasperated physician, after railing against the use of cows’ milk as an infant food at a 1909 conference in Connecticut on the prevention of infant mortality, reminded colleagues, “Nature’s normal nutriment does not predispose to death.”20

Figure 2.

Typical dairy barn with filthy floor, walls, and ceiling, circa 1900. "This is the kitchen where baby's breakfast is prepared," complained one doctor. Source: Milk and Its Relation to the Public Health. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1908.

Late-19th-century physicians were not only cognizant of the dangers cows’ milk posed to infants, they were equally conscious of the immunologic properties of human milk, and so they constantly decried the “children with weak and diseased constitutions belonging to that generally wretched class called bottle-fed.”21 In a series of experiments in 1912, pediatrician Henry L. Coit demonstrated how detrimental the milk of one species could be to the offspring of another. After feeding human milk to puppies, he found they “remained alive, but . . . in a very miserable condition.” In all his experiments, Coit discovered that newborn animals fed the milk of another species “were inferior to the breast-fed animals, both at the time of the experiment and afterwards.”22

Some doctors experienced the difficulties of artificial feeding on a personal as well as professional level. When pediatrician Dorothy Reed Mendenhall’s son, John, was 2 weeks old in 1912, she and a nurse drove from Chicago, where John was born, to Madison, Wis, where Mendenhall lived. It was a very hot day and during the long car ride the baby suffered convulsions. As Mendenhall recalled years later, “The excitement of the trip and my apprehension for John, dried up my milk and I never could furnish another drop.” Forced to resort to cows’ milk, she complained, “I literally took his milk apart and put it together again. I had him on fat free, sugar free, mineral free, and whey mixtures. Nothing seemed to help.” John did not return to his birth weight of over 8 pounds until he was 6 months old. Mendenhall maintained that if she had not been trained in pediatrics, he would have died.23

Mendenhall’s Herculean attempt to keep her artificially fed son alive was hardly unique. Women who did not breastfeed often experimented with assorted cows’ milk concoctions, usually futilely. Mayme Glover, despondent after moving from Minnesota to Champaign, Ill, in the summer of 1901, found that her artificially fed son’s chronic diarrhea exacerbated her misery. She wrote to family back in Minnesota, “We don’t dare to give the baby the water here it is too nasty for us even. . . . I have been trying to wash baby’s bottles but the kitchen is so nasty that even the water in the tea kettle is greasy.” The baby’s diarrhea did abate for a time under his mother’s care, and Mayme wrote happily one day, “Baby is real well. He has a quart of milk a day and sometimes we have to water it to make it hold out till the milk man comes at seven. . . . He is the happiest and best today that he has been yet since he began to ail.” However, James Glover did not survive his first year.24

CAMPAIGNS FOR “MORE MOTHER-FED BABIES” AND PURE COWS’ MILK

The poor health of artificially fed infants spawned widespread recognition by the 1910s. Two sets of public health campaigns resulted. One, designed almost solely by local public health officials, urged mothers to breastfeed for as long as possible. The other—involving public health departments and a much wider array of supporters, including concerned citizens, municipal government, medical charities, settlement houses, private physicians, and newspapers—crusaded for clean cows’ milk.

Calling pure cows’ milk “one of the essentials of daily living,” urban newspapers decried “the diluted, adulterated, and harmful quality of milk” common to US cities. As the country’s infant death rate garnered unprecedented concern, journalists charged that cows’ milk “plays no small part in this colossal crime of infanticide.”25 Reformers fought for pasteurized milk gathered from healthy cows, processed under sanitary conditions, sealed in individual bottles, and shipped in refrigerated railroad cars.26

While urban reformers focused on cleaning up cows’ milk, human milk advocates concentrated on keeping babies at the breast. One tool used in many cities was a home visit by public health nurses. In Chicago, beginning in the summer of 1908, Health Department officials sent nurses into neighborhoods with the highest death rates to discuss infant feeding with mothers.27 These officials, however, deemed the nonacculturation of immigrants to be at the root of infant mortality and so sent these nurses, always multilingual, only into immigrant neighborhoods, ignoring the plight of Black and native-born White infants.28 To augment these visits, the Chicago Department of Health also posted notices on the sides of buildings in 10 different languages to alert immigrant mothers to the importance of breastfeeding.29

While big cities like Chicago usually used the home visit for mass education—by unleashing nurses on neighborhoods to randomly catch mothers who might be home—Minneapolis used it, far more effectively, to address specific mother’s difficulties with breastfeeding. This tactic was the brainchild of Julius Parker Sedgwick, chief of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Minnesota. Sedgwick deemed human milk absolutely vital to infant health and urged in 1912 that breastfeeding be made “the keystone” of the national campaign to prevent infant mortality.30

Sedgwick’s philosophy inspired formation of the Breast Feeding Investigation Bureau of the Department of Pediatrics of the University of Minnesota in 1919. Under the bureau’s auspices, Minneapolis public health workers met with virtually every new mother immediately after the birth of her baby and as many times as necessary thereafter for the next 9 months, “even daily,” to help with lactation-related problems. This intense focus on the needs and concerns of new mothers and their babies paid off. During the bureau’s first year, 96% of babies born in Minneapolis breastfed through their second month and 72% breastfed through their ninth month.31 Infant deaths declined 20% that year.32 In contrast, Chicago, with its more haphazard approach to breastfeeding education, found in 1912 that even after 4 years of home visits by public health nurses—visits conducted immediately after a birth—supplementation with cows’ milk remained rampant. Only 39% of mothers exclusively breastfed their newborns.33

The Minneapolis medical community attributed their singular achievement almost solely to the multiple, timely home health visits. As one physician explained, “The importance of the personal visit of the nurse . . . cannot be overestimated. Mailing information does not get across. Pre-natal education as to breast feeding is often forgotten. The time to bring forward our facts is at the critical moment when the mother begins to doubt the advisability or the possibility of nursing her baby.”34 A Minneapolis Infant Welfare Society nurse agreed. Just when a mother was “most liable to discouragement [and] anxiety . . . convinced that her milk was not the right food,” the nurse arrived to alleviate maternal apprehension.35 In 1924, one doctor urged the nation’s medical community to follow the example of Minneapolis and view public health from a “business-like standpoint” and “rank the promulgation of breast feeding education as one of our best investments.”36

Figure 3.

Top: This Chicago Department of Health poster urged mothers to breastfeed and traced the perilous path of cows' milk from rural dairy farm to urban consumer. Source: Bulletin: Chicago School of Sanitary Instruction (June 3, 1911).14

Bottom: A Chicago Department of Health poster explains to mothers how to make cows' milk safer for bottle-fed babies. Source: Bulletin: Chicago School of Sanitary Instruction (August 31, 1912).15

THE FALL AND RISE OF BREASTFEEDING INITIATION RATES

Yet breastfeeding never became the cornerstone of preventive medicine that so many early-20th-century physicians recommended. Instead, the lay and medical communities came to believe that pasteurization nullified the differences between human and cows’ milk. With readily available clean cows’ milk, breastfeeding crusades and breastfeeding itself seemed antiquated and unnecessary. By the early 1930s, a new generation of doctors belittled human milk as “nothing . . . sacred.”37 Unlike their breastfeeding-activist predecessors, these pediatricians never witnessed the “slaughter”38 of infants by spoiled and adulterated cows’ milk and so came to place more faith in the efficacy of cows’ milk than human milk.

From 1930 to the early 1970s, now with the collusion of physicians, not only did mothers continue to supplement their breast milk with cows’ milk and wean infants in the first few weeks and months of life, but more and more mothers did not breastfeed at all. By 1971, breastfeeding had reached an all-time low in the United States. Only 24% of mothers initiated breastfeeding—that is, only 24% breastfed at least once before hospital discharge.39 Not until later in the 1970s did the feminist-inspired women’s health reform movement rekindle interest in breastfeeding. One young mother, caught up in the social activism of the 1970s, recalled how the politics and communalism of the time heralded new infant care practices. Her daughter “never drank out of a bottle. . . . When we needed a baby sitter, there were always other nursing moms in the neighborhood willing to take her. We all nursed each other’s babies. In fact, it seemed that every woman I knew was nursing.”40

Yet the breastfeeding initiation rate has not seen the steady increase that this woman and her cohorts might have predicted in the 1970s. Rather, the rate has inexplicably receded and surged. Between 1984 and 1989, initiation rates declined 13%, from almost 60% to 52%. Not until 1995 did these rates return to their high of 60%.41 And in December 2002, the Ross Products Division of Abbott Laboratories reported the highest rates since the company began collecting data in 1955. In 2001, 69.5% of US mothers initiated breastfeeding.42

The medical community deemed this increase particularly significant because the bulk of the increase was among those least likely to breastfeed in recent history—Black women, women educated only through high school, and women enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Indeed, breastfeeding habits in the last 30 years have differed according to class and race in a much starker way than they did a century ago. Only one group of women have embraced breastfeeding in large numbers since the early 1970s—White, college-educated women.43 Not only have Black women initiated breastfeeding at roughly half the rate of White women, but the majority of Black women who do breastfeed introduce formula to their infants while still in the hospital.44 The race gap in breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and duration rates is, in fact, so cavernous that one group of researchers argues that convincing more Black women to breastfeed and to breastfeed longer would narrow the race gap in infant mortality—currently 1.3 times higher for Blacks than Whites—as significantly as preventing low birthweight, once thought to be the primary, if not sole, reason for the high Black infant death rate.45

The news of the recent increase in breastfeeding gratified many in the medical community. Ruth Lawrence, a neonatologist and pediatrician at the University of Rochester Medical School, told USA Today that it was “the best news I’ve heard for children in a long time.” She warned, however, “We still have a long way to go.”46 While the rise is significant because it occurred among women who have not recently embraced breastfeeding as a viable and beneficial infant feeding method, the habit of introducing formula well before 6 months persists among all women who initiate breastfeeding. Despite the advice of both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the World Health Organization (WHO) that infants should exclusively breastfeed for 6 months—that is, consume no other food, not even water, during this time—only 17% of American women adhere to the recommendation.47 Fifty-three percent of lactating mothers introduce formula before their babies are a week old, 68% do so by 2 months, and 81% by 4 months.48

Breastfeeding duration rates are lower still. Although the AAP counsels mothers to breastfeed babies for at least a year (and the WHO recommends at least 2 years), fewer than 5% of American mothers are still breastfeeding when they celebrate their babies’ first birthday.49 Since dozens of recent studies show that how long a mother feeds her baby human milk exclusively, and how long a mother continues to breastfeed thereafter, are more meaningful predictors of health than the simple fact that a child was ever breastfed, persistently low exclusivity and duration rates continue to spark concern in the medical and public health communities despite the recent rise in initiation rates.

HUMAN MILK AND HUMAN HEALTH: A DOSE–RESPONSE RELATIONSHIP

The current customs of supplementing breast milk with formula early in an infant’s life and then discontinuing breastfeeding altogether after a few weeks or months are identical to the practices a century ago that prompted municipalities to alert mothers to the connection between infant mortality and babies’ consumption of cows’ milk. Today we are in a similar situation as studies alert physicians to what their forebears well knew: formula and the concomitant dearth of human milk in an infant’s diet can herald ill health for years.

The shift from breast to bottle essentially redefined “normal” infant health. As early as the 1930s, pediatricians deemed strings of respiratory, ear, and gastrointestinal infections inevitable childhood events. Only with the upswing in breastfeeding initiation rates in the 1970s did the medical community once again link formula feeding with sick children.50 One cannot help but recall Henry Coit’s 1912 experiment in which he fed human milk to puppies. Would Coit have described today’s artificially fed children—with their significantly higher rates of ear infections, stomachaches, and runny noses—as he did those unfortunate pups: as being, in a strictly dispassionate clinical sense, “in a miserable condition” or “inferior” to breastfed infants?51

More recently, researchers have connected not just acute illness but a host of serious, chronic diseases and conditions—SIDS, obesity, leukemia, breast cancer, asthma, and lowered IQ—to infants’ consumption of formula. These studies are especially significant because they demonstrate that not only initiation of breastfeeding, but exclusivity and duration of breastfeeding, matter. There is a dose–response relationship between human milk and human health. Researchers have found, for example, that babies breastfed for less than 4 weeks are 5 times more likely to die of SIDS than infants breastfed for more than 16 weeks.52 The early introduction of formula also increases the incidence of childhood obesity. Babies breastfed 2 months or less are almost 4 times more likely than babies breastfed for more than a year to be obese when they enter elementary school.53 Childhood cancer rates are affected by how infants are fed as well. Infants breastfed for 6 months or less are almost 3 times more likely to contract a lymphoid malignancy than babies breastfed longer than 6 months.54

Recently, the media alerted the public to an epidemic of asthma among children. Medical journals have linked that epidemic, in part, to formula feeding. In September 1999, the British Medical Journal reported that 3 factors are associated with the development of asthma: gestational age less than 37 weeks, household smoking, and the introduction of formula before 4 months of age. In another asthma study, researchers grouped breastfed infants according to how long they had been breastfed: less than 2 months, 2 to 6 months, 7 to 9 months, and longer than 9 months. After controlling for household smoking, low birth weight, and low maternal education, investigators found that breastfeeding for only 9 months or less was a risk factor for asthma.55 Scientists have linked the early introduction of formula to lowered intelligence as well. In the most recent of several articles on the subject, researchers in the May 2002 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association studied 3253 Danish men and women and found that the more human milk they had consumed through 9 months of age, the higher they scored on intelligence tests in their late teens and 20s.56

Mothers even influence their own health when they breastfeed, and here, too, breastfeeding duration is important. A study in the American Journal of Epidemiology in 2000 found that women who breastfed each of their children for only 1 to 6 months were twice as likely to suffer from either premenopausal or postmenopausal breast cancer than women who breastfed each of their children for more than 2 years. Authors of a subsequent study likewise discovered that the longer women breastfed, the less likely they were to get breast cancer. After examining data from women in 30 countries, these researchers estimated that if every mother in the United States breastfed her babies only 6 months longer than originally planned, there would be 250 000 fewer cases of breast cancer in the country each year.57

INCREASING BREASTFEEDING RATES TODAY

With contemporary asthma and obesity epidemics among children and health care costs soaring, increasing breastfeeding rates is a logical avenue to both improved child health and diminished costs.58 Recognizing this, several organizations in recent years initiated breastfeeding promotions heralding breastfeeding as preventive medicine at its best. The first organization to do so was the AAP in 1997 with their widely publicized policy statement, “Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk.” The statement enumerated the numerous acute and chronic diseases thwarted or limited in severity by breastfeeding. It also encouraged mothers to consider breastfeeding exclusivity and duration rates, rather than focusing solely on initiating breastfeeding, by advising exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months, continued breastfeeding until an infant was at least a year old, and breastfeeding thereafter for as long as mother and baby desired.59 Headlines announcing the new guidelines appeared in every major American newspaper and prompted discussion on television news shows for several days.60

Three years later, with considerably less fanfare albeit using more forceful prose, the Department of Health and Human Services (HSS) published a booklet titled HHS Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding. HHS called the lack of exclusive and prolonged breastfeeding in the United States “a public health challenge” and urged health care providers, employers, and child care facilities to formulate policies supportive of extended breastfeeding. HHS also called for a social marketing effort to explain to the public the importance of human milk and the dangers of formula feeding to the nation’s babies.61

In June 2002, the Ad Council responded to that call. The Ad Council—renowned for its ability to alter human behavior and attitudes via such memorable public service announcements as “You Can Learn a Lot From a Dummy” and “Friends Don’t Let Friends Drive Drunk”—announced that its next task would be to formulate a campaign to convince Americans of the importance of breastfeeding.62 Those ads, which had not yet appeared at press time, might influence breastfeeding rates as profoundly as the Ad Council has affected seat belt use, particularly if they speak to the women least likely to breastfeed today, most notably Black and low-income women.

Although today’s breastfeeding campaigns are not as visible as yesteryear’s (which will no doubt change after the Ad Council weighs in), the AAP statement and the HHS booklet suggest that today’s medical community recognizes what their predecessors knew a century ago—that the American propensity to shun human milk is a public health problem and should be exposed and managed as such. The first sentence of the HHS piece—“Breastfeeding is one of the most important contributors to infant health”—is reminiscent of the early-20th-century public health campaigns’ insistence that having been breastfed was the single most powerful predictor of an infant’s ability to survive childhood. The HHS booklet was a clarion call to Americans. How that challenge will be met is still to be seen.

CAN HISTORY INFORM BREASTFEEDING CAMPAIGNS TODAY?

Perhaps history can help steer today’s nascent campaigns clear of the mistakes made by earlier crusades, which looked largely to cows’ milk as the solution for too little breastfeeding. Those crusades, in fact, led to our current ambivalence about breastfeeding. The efforts at the turn of the 20th century to simultaneously promote breastfeeding and provide palatable cows’ milk to babies sent a mixed message to mothers. Society has perpetuated that ambiguity ever since. Even as more women in the 1970s nursed their infants, the medical community never deemed breastfeeding the standard of care. Rather, formula feeding remained the norm and nursing became the “best” thing to do, akin to putting cotton clothing on your baby rather than polyester—a nice touch, but unnecessary.

As lactation specialist Diane Wiessinger explains, “Our own experience tells us that optimal is not necessary. Normal is fine, and implied in this language is the absolute normalcy—and thus safety and adequacy—of artificial feeding.” Wiessinger suggests that the medical community can help the public think of breastfeeding as standard with more accurate language. “Because breastfeeding is the biological norm, breastfed babies are not ‘healthier;’ artificially-fed babies are ill more often and more seriously.”63

In recognizing the power of language, the medical community can also do something their forebears did not do a century ago: define breastfeeding. In 1900, while the vast majority of mothers unquestionably initiated breastfeeding, they did it neither exclusively nor for very long. The AAP attempted to clarify the more than century-old misinterpretation of what constitutes breastfeeding when the organization issued its breastfeeding guidelines 5 years ago. The recommendation that mothers breastfeed their infants exclusively for 6 months served to differentiate between breastfeeding and the more common practice of supplementing breast milk with formula. The admonition that mothers should continue to breastfeed for at least a year, and “thereafter for as long as mutually desired,” stressed that duration is a vital component of breastfeeding.64

The statement also implied that the child has agency, which represents a real change in the medical/maternal view of the breastfeeding relationship. Yet newspaper headlines invariably misrepresented the suggested timetables and their implication. The most common distortion of the guideline was to state that the AAP advised breastfeeding babies for one year, intimating that (1) the AAP opposes breastfeeding for more than a year, (2) supplementation with formula is a normal adjunct to breastfeeding, and (3) weaning should be done by the clock and not according to either a mother’s or a child’s desires.65

When early-20th-century public health officials sent visiting nurses into neighborhoods with the highest infant death rates to discuss infant feeding with mothers, they recognized the public health advantages of targeting the women least likely to breastfeed. As the latest Ross survey indicates, this remains a vital lesson.66 Recent tactics to get these particular women’s attention have been employed successfully. Changes in WIC policy to promote breastfeeding, rather than simply to supply free formula to low-income mothers, were instrumental in effecting the recent increase in breastfeeding initiation.67 Some hospitals have likewise focused on intense breastfeeding education with similar success. The hospital of the Medical University of South Carolina, whose largely Black population of birthing mothers breastfed at rates well below the national average, successfully increased rates between 1993 and 1999. Via training for hospital personnel and pre- and postnatal patients, the university raised breastfeeding initiation rates from 18.9% to 47.1% among all mothers and from 19.2% to 60.8% among mothers of preterm infants.68

The lesson to be learned from the WIC and the Medical University of South Carolina (and the intensive postnatal home visits in Minneapolis more than 80 years ago) is clear. The success of any breastfeeding educational campaign relies on readily available personnel able to support breastfeeding mothers with accurate information and kind, enthusiastic, persistent assistance. Yet it is so rare for medical schools to spend any time teaching medical students about lactation and human milk that whether a physician or a physician’s wife has breastfed is the best predictor of a doctor’s ability and willingness to give accurate advice and appropriate support to lactating mothers.69 Unless medical schools incorporate the teaching of lactation physiology, breastfeeding management, and the relationship between human milk and human health into their curriculums, the dearth of knowledge about breastfeeding among medical professionals will continue to match the dearth of human milk, and the abundance of formula, available to babies.

While the advice meted out by physicians is formed by the cultural milieu of medicine, health choices made by consumers are similarly shaped more by economic and social forces than health warnings. In the case of infant feeding decisions, American women are thwarted in their ability to choose the healthy option by the demands of work outside the home and lack of societal support for new mothers. Today, more than half of women in the United States with children less than a year old work outside the home. Yet there is almost no evidence of employers accommodating lactating employees. The vast majority of working women who are breastfeeding their babies have no access at work to a private place to pump milk, a refrigerator to store milk, or breastfeeding breaks to nurse a nearby infant.70 Absent prolonged, paid maternity leave, on-site day care, accommodations at work, and flexible work hours, working women will continue to find breastfeeding difficult.

While the initiation of breastfeeding appears to be unaffected by a mother’s employment status, breastfeeding duration is decidedly influenced by full-time maternal employment, not unlike a century ago.71 Only 10% of full-time working mothers breastfeed their 6-month-olds compared with almost 3 times that number of stay-at-home mothers. This association between maternal employment and decreased breastfeeding duration is evident across all ethnic, education, and age groups.72 The current Family and Medical Leave Act, mandating only 12 weeks of maternity leave, unpaid no less, is only one example of the failure of contemporary American society to recognize the reality of mothers’ lives and their need for social support in order to meet the nutritional, immunologic, psychological, developmental, and cognitive needs of their babies.73

Increasing breastfeeding initiation and, especially, exclusivity and duration rates will take planned effort. As in the 19th century, the societal definition of appropriate infant care is a more powerful shaper of human behavior than health warnings. Supplementing breast milk with formula early in an infant’s life and discontinuing breastfeeding after a few weeks or months have been culturally acceptable practice for more than a century. To make breastfeeding the standard of care, health care providers can play an important role but rarely take the opportunity. Currently, only 8% to 24% of women report receiving guidance about infant feeding from their physician.74 Yet 80 years ago in Minneapolis, prompt, informed assistance from visiting nurses dramatically increased breastfeeding rates and lowered infant mortality in a single year. Similar efforts focusing on supporting and encouraging breastfeeding among women transformed mothers’ practice at the Medical University of South Carolina and in WIC offices around the country.75 All 3 endeavors made breastfeeding not just the healthy thing to do but the socially acceptable, “normal” thing to do.

With the pasteurization of cows’ milk, society lost what had been ubiquitous medical knowledge—that the adequate consumption of human milk as an infant and toddler is a powerful guarantor of health and long life. Forgetting the history of the struggle to lower infant mortality and morbidity can be equally dangerous. The maintenance of infant health has long been recognized as one of society’s best investments. In that tradition, the medical and public health communities should acknowledge what the first generation of American pediatricians and infant welfare reformers promulgated: infants’ and toddlers’ failure to consume sufficient human milk has vital implications for public health.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Benita Blessing, Lawrence M. Gartner, Norman Gevitz, Katherine Jellison, Sam Wilen, Robert V. Wolf, and 2 anonymous reviewers for their critiques of previous versions of this article.

Peer Reviewed

Endnotes

- 1.Bulletin: Chicago School of Sanitary Instruction 14 (3June1911): back page.

- 2.Bulletin: Chicago School of Sanitary Instruction 15 (31August1912): 140. [Google Scholar]

- 3.In this era before access to ice and refrigeration, breastfeeding was especially important during hot weather. Therefore, mothers never weaned during the summer and customarily breastfed their babies through at least 2 summers. Marylynn Salmon, “The Cultural Significance of Breastfeeding and Infant Care in Early Modern England and America,” Journal of Social History 28 (Winter 1994): 247–269. [Google Scholar]

- 4.“The Care of Infants Historical Data,” Journal of the American Medical Association 59 (1912): 542–543. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Letter from Martha Luey Parish to Lestern, Annie and Father, November 2, 1884, Parish Family Letters, Newberry Library, Chicago.

- 6.“The Mother’s Parliament,” Babyhood 3 (April1887): 170. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Josephine K. Laflin Diary, 1903–1907, March 31, 1903 entry, Laflin Family Papers, Chicago Historical Society.

- 8.For a more detailed explanation of the complex reasons behind women’s changing infant feeding habits than what is contained in this paragraph, see Jacqueline H. Wolf, Don’t Kill Your Baby: Public Health and the Decline of Breastfeeding in the 19th and 20th Centuries (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2001), 9–41.

- 9.Maria M. Vinton, “Baby’s First Month,” Mother’s Nursery Guide 9 (February1893): 69. [Google Scholar]

- 10.“Nursery Problems,” Babyhood 2 (July1886): 291. For more on the growing intimacy between husbands and wives, see John D’Emilio and Estelle B. Freedman, Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Many cities housed Little Mothers Clubs, organizations customarily affiliated with public schools or settlement houses. These clubs trained young girls to better care for the infant siblings so often left in their charge. See Rima D. Apple, Mothers & Medicine: A Social History of Infant Feeding 1890–1950 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987), 102–103; Wolf, Don’t Kill Your Baby, 21–22, 120–121.

- 12.Samuel H. Preston and Michael R. Haines, Fatal Years: Child Mortality in Late Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), 27.

- 13.Infant deaths from diarrhea soared in big cities each summer. One study conducted in Berlin in 1901, however, showed that these summer deaths were virtually nonexistent among breastfed children. See Preston and Haines, Fatal Years, 27–28. In another study of almost 2000 infants who died of “degenerative disturbances,” physicians noted that only 3% had been breastfed. In an additional study of 718 babies who died of diarrhea, only 4% were breastfed. Frank Spooner Churchill, “Infant Feeding,” Chicago Medical Recorder 10 (February1896): 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathan Allen, “The Decline of Suckling Power Among American Women,” Babyhood 5 (March1889): 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- 15.S. T. Rorer, “The Proper Food for a Child in Summer,” Ladies’ Home Journal 17 (July1900): 26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.For a history of wet nursing and its ramifications for both the wet nursed infants and the infants of wet nurses, see Janet Golden, A Social History of Wet Nursing in America: From Breast to Bottle (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Wolf, Don’t Kill Your Baby, 132–157.

- 17.Report of the Department of Health of the City of Chicago for the Years 1907, 1908, 1909, 1910 (Chicago, 1911), 174.

- 18.For a complete explanation of these statistics, see Wolf, Don’t Kill Your Baby, xiv, 208–211.

- 19.Effa V. Davis, “Breast Feeding,” Bulletin: Chicago School of Sanitary Instruction 13 (8June1910): 2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ira S. Wile, “Educational Responsibilities of a Milk Depot,” in Prevention of Infant Mortality, Being the Papers and Discussion of a Conference Held at New Haven, Connecticut, November 11, 12, 1909 (N.p., n.d.), 139–153.

- 21.W. Thornton Parker, “The Refusal to Nurse and Its Consequences,” Babyhood 3 (August1887): 313. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henry L. Coit, “The Effects of Heated and Superheated Milk on the Infant’s Nutrition (Recent Investigations),” Transactions of the American Pediatric Society 24 (1912): 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- 23.“Dorothy Reed Mendenhall’s Autobiography,” 1939, typed manuscript, Dorothy Reed Mendenhall Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Neilson Library, Smith College, Northampton, Mass.

- 24.Family tree and letters dated July 10, 13, and 16, 1901, Mary Scofield and Family Papers, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minn.

- 25.“Scarcely Any Pure Milk,” Chicago Daily News (September 1, 1892), 2; “Stop the Bogus Milk Traffic,” Chicago Tribune (September 23, 1892), 4.

- 26.In Chicago, the milk crusades began in 1892 and continued for more than 30 years. There was no legal requirement to seal milk vats until 1904, to bottle milk in individual bottles until 1912, to pasteurize milk until 1916, to keep milk cold during shipping until 1920, or to test cows for bovine tuberculosis until 1926. For more on the milk crusades in Chicago, see Wolf, Don’t Kill Your Baby, 42–73. For the story of pure milk campaigns in other cities, see Judith Walzer Leavitt, The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982), 156–189; Richard A. Meckel, Save the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850–1929 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), 62–91.

- 27.“Infant Welfare Service 1909–1910,” in Report of the Department of Health of the City of Chicago for the Years 1907, 1908, 1909, 1910 (Chicago, 1911), 170–180.

- 28.Letter to Mrs. Ba. A. Eckhart from Edna L. Foley, January 16, 1923, Visiting Nurse Association of Chicago Papers, Chicago Historical Society. For more on the attention paid by public health departments to the infants of immigrants at the expense of their Black and native-born White counterparts, see Lynne Curry, Modern Mothers in the Heartland: Gender, Health, and Progress in Illinois, 1900–1930 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1999), 10–11, 35–36.

- 29.Posters appeared in English, Bohemian, Croatian, German, Italian, Lithuanian, Polish, Serbian, Swedish, and Yiddish.

- 30.Julius Parker Sedgwick, “Maternal Feeding,” The American Journal of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children 66 (1912): 857–865. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Julius Parker Sedgwick, “A Preliminary Report of the Study of Breast Feeding in Minneapolis,” Transactions of the American Pediatric Society 32 (1920): 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- 32.J. P. Sedgwick and E. C. Fleischner, “Breast Feeding in the Reduction of Infant Mortality,” American Journal of Public Health 11 (1921): 153–157. This was especially significant because as late as 1948 the law did not require that milk sold in Minneapolis be pasteurized. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.“Infant Welfare Field Work,” Report and Handbook of the Department of Health of the City of Chicago for the Years 1911 to 1918 Inclusive (Chicago, 1919), 567.

- 34.E. J. Huenekens, “Breast Feeding,” American Journal of Nursing 24 (1924): 751–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.N. C. Rudd, “Breast Feeding in Minneapolis,” Mother and Child 2 (1921): 171–173. [Google Scholar]

- 36.E. J. Huenekens, “Breast Feeding From a Public Health Standpoint,” American Journal of Public Health 14 (1924): 391–394. For a more detailed analysis of the work in Minneapolis, see Jacqueline H. Wolf, “ ‘Let Us Have More Mother-Fed Babies’: Early Twentieth-Century Breastfeeding Campaigns in Chicago and Minneapolis,” Journal of Human Lactation 15 (1999): 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.“Are Infant Feeding Methods Changing?” Public Health Nursing 23 (1931): 581–585. [Google Scholar]

- 38.“Slaughter of the Innocents,” Chicago Tribune, 23August1892, 6.

- 39.Allan S. Ryan, David Rush, Fritz W. Krieger, and Gregory E. Lewandowski, “Recent Declines in Breast-Feeding in the United States, 1984 Through 1989,” Pediatrics 88 (1991): 719–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.North Country Co-op (Minneapolis, Minn) Records, 1972–2000, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minn.

- 41.Alan S. Ryan, “The Resurgence of Breastfeeding in the United States,” Pediatrics 99 (1997): E12, available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/99/4/e12, accessed October 10, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alan S. Ryan, Zhou Wenjun, and Andrew Acosta, “Breastfeeding Continues to Increase Into the New Millennium,” Pediatrics 110 (2002): 1103–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan et al., “Resurgence of Breastfeeding”; Ryan et al., “Breastfeeding Continues to Increase”; Alain Joffe and Susan M. Radius, “Breast Versus Bottle: Correlates of Adolescent Mothers’ Infant-Feeding Practices,” Pediatrics 79 (1987): 689–695; Ryan et al., “Recent Declines in Breast-Feeding”; Christine E. Peterson and Julie DaVanzo, “Why Are Teenagers in the United States Less Likely to Breast-Feed Than Older Women?” Demography 29 (1992): 431–450; Ayala Gabriel, K. Ruben Gabriel, and Ruth A. Lawrence, “Cultural Values and Biomedical Knowledge: Choices in Infant Feeding,” Social Science and Medicine 23 (1986): 501–509; Natalie Kurinij, Patricia H. Shiono, and George G. Rhoads, “Breast-Feeding Incidence and Duration in Black and White Women,” Pediatrics 81 (1988): 365–371.3575023 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurinij et al., “Breastfeeding Incidence”; Ryan et al., “Recent Declines in Breastfeeding”; Renata Forste, Jessica Weiss, and Emily Lippincott, “The Decision to Breastfeed in the United States: Does Race Matter?” Pediatrics 108 (2001): 291. –296. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Forste et al., “Decision to Breastfeed.”

- 46.Marilyn Elias, “US Breast-Feeding Rate Soars,” USA Today, 1December2002, available at: http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2002-12-01-feeding-usat_x.htm, accessed December 2, 2002.

- 47.American Academy of Pediatrics, “Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk,” Pediatrics 100 (1997): 1035–1039; World Health Organization, “The Optimal Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding,” Note for the Press No. 7, April 2, 2001, available at: www.who.int/inf-pr-2001/en/note2001-07.html, accessed October 10, 2002; Ryan et al., “Breastfeeding Continues to Increase.”9411381 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Ruowei, Cynthia Ogden, Carol Ballew, Cathleen Gillespie, and Laurence Grummer-Strawn, “Prevalence of Exclusive Breastfeeding Among US Infants: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Phase II, 1991–1994),” American Journal of Public Health 92 (2002): 1107–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryan, “Resurgence of Breastfeeding.”

- 50.For information on the relationship between formula feeding and otitis media, see Nancy F. Sheard, “Breast-Feeding Protects Against Otitis Media,” Nutrition Reviews 51 (1993): 275–277; B. Duncan, J. Ey, C. J. Holberg, A. L. Wright, F. D. Martinez, and L. M. Taussig, “Exclusive Breast-Feeding for at Least 4 Months Protects Against Otitis Media,” Pediatrics 91 (1993): 867–872; G. Aniansson, “A Prospective Cohort Study on Breast-Feeding and Otitis Media in Swedish Infants,” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 13 (1994): 183–187. For information on the relationship between formula feeding and gastrointestinal disease, see A. S. Goldman, “Modulation of the Gastrointestinal Tract of Infants by Human Milk, Interfaces and Interactions: An Evolutionary Perspective,” Journal of Nutrition 130 (2000): 426S–431S; L. K. Pickering and A. L. Morrow, “Factors in Human Milk That Protect Against Diarrheal Disease,” Infection 2 (1993): 355–357; Amal K. Mitra and Fauziah Rabbani, “The Importance of Breastfeeding in Minimizing Mortality and Morbidity From Diarrhoeal Diseases: The Bangladesh Perspective,” Journal of Diarrhoeal Diseases Research 13 (1995): 1–7. For information on the relationship between lower respiratory tract infections and formula feeding, see A. L. Wright, C. J. Holberg, F. D. Martinez, W. J. Morgan, and L. M. Taussig, “Breast Feeding and Lower Respiratory Tract Illness in the First Year of Life,” British Medical Journal 299 (1989): 946–949; Y. Chen, “Synergistic Effect of Passive Smoking and Artificial Feeding on Hospitalization for Respiratory Illness in Early Childhood,” Chest 95 (1989): 1004–1007; A. L. Wright, C. J. Holberg, L. M. Taussig, and F. D. Martinez, “Relationship of Infant Feeding to Recurrent Wheezing at Age 6 Years,” Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 149 (1995): 758–763. See also Paula D. Scariati, Laurence M. Grummer-Strawn, and Sara Beck Fein, “A Longitudinal Analysis of Infant Morbidity and the Extent of Breastfeeding in the United States,” Pediatrics 99 (1997): E5, available at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/99/6/e5, accessed October 11, 2002.8247421 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coit, “Effects of Heated and Superheated Milk.”

- 52.B. Alm, G. Wennergren, S. G. Norvenius, et al., “Breast Feeding and the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in Scandinavia, 1992–95,” Archives of Disease in Childhood 86 (2002): 400–402. One recent article in Pediatrics argues that the race gap in infant mortality in the United States is directly linked to the race gap in breastfeeding rates; see Forste et al, “Decision to Breastfeed.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rüdiger von Kries, Berthold Koletzko, Thorsten Sauerwald, et al., “Breast Feeding and Obesity: Cross Sectional Study,” British Medical Journal 319 (1999): 147–150; Matthew W. Gillman, Sheryl L. Rifas-Shiman, Carlos A. Camargo Jr., et al., “Risk of Overweight Among Adolescents Who Were Breastfed as Infants,” Journal of the American Medical Association 285 (2001): 2461–2467.10406746 [Google Scholar]

- 54.A. Bener, S. Denic, and S. Galadari, “Longer Breast-Feeding and Protection Against Childhood Leukaemia and Lymphomas,” European Journal of Cancer 37 (2001): 234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.W. H. Oddy, P. G. Holt, P. D. Sly, et al., “Association Between Breastfeeding and Asthma in 6 Year Old Children: Findings of a Prospective Birth Cohort Study,” British Medical Journal 319 (1999): 815–819; S. Dell, “Breastfeeding and Asthma in Young Children: Findings From a Population-Based Study,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 155 (2001): 1261–1265. See also K. A. W. Karunasekera, J. A. C. T. Jayasinghe, and L. W. G. R. Alwis, “Risk Factors of Childhood Asthma: A Sri Lankan Study,” Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 47 (2001): 142–145.10496824 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Erik Lykke Mortensen, Kim Fleischer Michaelsen, Stephanie A. Sanders, and June Machover Reinisch, “The Association Between Duration of Breastfeeding and Adult Intelligence,” Journal of the American Medical Association 287 (2002): 2365–2371. See also S. W. Jacobson and J. L. Jacobson, “Breastfeeding and IQ: Evaluation of the Socio-Environmental Confounders,” Acta Paediatrica 91 (2002): 258–260; Ann Reynolds, “Breastfeeding and Brain Development,” Pediatric Clinics of North America 48 (2001): 159–171; N. Gordon, “Nutrition and Cognitive Function,” Brain & Development 19 (1997): 165–170; C. I. Lanting, S. Patandin, N. Weisglas-Kuperus, B. C. Touwen, and E. R. Boersma, “Breastfeeding and Neurological Outcome at 42 Months,” Acta Paediatrica 87 (1998): 1224–1229. Researchers have also demonstrated that the higher IQs of breastfed babies are linked to undetermined properties in human milk rather than the act of breastfeeding. See A. Lucas, R. Morley, T. J. Cole, G. Lister, and C. Leeson-Payne, “Breast Milk and Subsequent Intelligence Quotient in Children Born Preterm,” Lancet 339 (1992): 261–264. In this study, premature infants fed human milk only by gavage scored significantly higher on IQ tests in later years than premature infants fed formula by gavage.11988057 [Google Scholar]

- 57.T. Zheng, L. Duan, Y. Liu, et al., “Lactation Reduces Breast Cancer Risk in Shandong Province, China,” American Journal of Epidemiology 152 (2000): 1129–1135; Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, “Breast Cancer and Breastfeeding: Collaborative Reanalysis of Individual Data From 47 Epidemiological Studies in 30 Countries, Including 50,302 Women With Breast Cancer and 96,973 Women Without the Disease,” Lancet 360 (2002): 187–195. See also T. Zheng, T. R. Holford, S. T. Mayne, et al., “Lactation and Breast Cancer Risk: A Case–Control Study in Connecticut,” British Journal of Cancer 84 (2001): 1472–1476.11130618 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Studies demonstrate this. See, for example, R. Cohen, M. B. Mrtek, and R. G. Mrtek, “Comparison of Maternal Absenteeism and Infant Illness Rates Among Breast-Feeding and Formula-Feeding Women in Two Corporations,” American Journal of Health Promotion 10 (1995): 148–153; C. Hoey and J. L. Ware, “Economic Advantages of Breast-Feeding in an HMO Setting: A Pilot Study,” American Journal of Managed Care 3 (1997): 861–865; Thomas M. Ball and A. L. Wright, “Health Care Costs of Formula-Feeding in the First Year of Life,” Pediatrics 103 (1999): 870–876; Thomas M. Ball and David M. Bennett, “The Economic Impact of Breastfeeding,” Pediatric Clinics of North America 48 (2001): 253–262.10160049 [Google Scholar]

- 59.American Academy of Pediatrics, “Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk.”

- 60.Electronic and print media around the country and the world covered the announcement of the AAP’s new breastfeeding guidelines, including ABC World News Tonight, The Today Show, CNN, MSNBC, National Public Radio, United Press International, Associated Press, the London Daily Mail, Time magazine, and the New York Times. Articles included the following: Laura Githens, “Breast-Feeding for a Year? Easier Said Than Done,” Buffalo News, December 3, 1997, 1D; “Longer Time Urged for Breastfeeding,” Los Angeles Times, December 3, 1997, 14; Sharon Voas, “Babies Need Mom’s Milk; 1 Year Minimum, Pediatricians Urge,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 3, 1997, A1; Jim Ritter, “Moms Urged to Breast-Feed Babies Longer; Doctors Push 1-Year Minimum,” Chicago Sun-Times, December 2, 1997, 1; Marilyn Elias, “Nurse for Full Year, Moms Urged,” USA Today, December 2, 1997, 1A; “Pediatrics Group Endorses 1 Year of Breast-Feeding,” Washington Post, December 2, 1997, A14.

- 61.HHS Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding (Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women’s Health, 2000).

- 62.On June 19, 2002, the Ad Council issued a press release announcing plans for the formulation of 3 new public service announcements: to promote interracial cooperation, to improve literacy rates, and to educate Americans about breastfeeding. See http://www.adcouncil.org/about/news061902, accessed June 27, 2002. For information on the Ad Council and its work, see www.adcouncil.org.

- 63.Diane Wiessinger, “Watch Your Language!” Journal of Human Lactation 12 (1996): 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.American Academy of Pediatrics, “Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk.”

- 65.A few representative headlines in the immediate aftermath of the AAP announcement include the following: “Mothers Urged to Breast-Feed a Year,” Portland Press Herald, December 3, 1997, 7A; Marilyn Elias, “Breastfeeding Urged for First 12 Months,” Denver Post, December 2, 1997, A4; “Guidelines Urge Moms to Breast-Feed to Year,” Dayton Daily News, December 3, 1997.

- 66.Ryan et al., “Breastfeeding Continues to Increase.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.A. L. Wright, “The Rise of Breastfeeding in the United States,” Pediatric Clinics of North America 48 (2001): 1–12; I. B. Ahluwalia, I. Tessaro, L. M. Grummer-Strawn, C. MacGowan, and S. Benton-Davis, “Georgia’s Breastfeeding Promotion Program for Low-Income Women,” Pediatrics 105 (2000): E85, available at: http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/105/6/e85, accessed February 24, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carol L. Wagner, Thomas C. Hulsey, W. Michael Southgate, and David J. Annibale, “Breastfeeding Rates at an Urban Medical University After Initiation of an Educational Program,” Southern Medical Journal 95 (2002): 909–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.G. L. Freed, S. J. Clark, J. Sorenson, J. A. Lohr, R. Cefalo, and P. Curtis, “National Assessment of Physicians’ Breast-feeding Knowledge, Attitudes, Training and Experience,” Journal of the American Medical Association 273 (1995): 472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laura Duberstein Lindberg, “Trends in the Relationship Between Breastfeeding and Postpartum Employment in the United States,” Social Biology 43 (1996): 191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.It is not affected by part-time employment, however. Part-time work can be an effective strategy if a mother wants to combine breastfeeding and work. See Sara B. Fein and Brian Roe, “The Effect of Work Status on Initiation and Duration of Breast-Feeding,” American Journal of Public Health 88 (1998): 1042–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Joan Y. Meek, “Breastfeeding in the Workplace,” Pediatric Clinics of North America 48 (2001): 461–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.For discussions of the history of mothers and infant nurture, as well our knowledge of infant needs, see Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants, and Natural Selection (New York: Pantheon Books, 1999); Deborah Blum, Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Affection (Cambridge, Mass: Perseus Publishing, 2002). Hrdy in particular takes contemporary feminists to task for their denial of infants’ needs. Most developed countries have taken the needs of working mothers and their infants into account via legislation. In Europe, for example, where paid maternity leave is the norm, there is not only the legal requirement that women must be treated equally, women are also given special protections in areas where their unique ability to bear and breastfeed children might put them at a disadvantage. This is antithetical to US policy guaranteeing women equal treatment—that is, the same treatment as men—in the workplace. This puts women with very young children at an inherent disadvantage to men. See Nora V. Demleitner, “Maternity Leave Policies of the United States and Germany: A Comparative Study,” New York Law School Journal of International and Comparative Law 13 (1992): 229–255.

- 74.Meek, “Breastfeeding in the Workplace,” 465.

- 75.Wagner et al., “Breastfeeding Rates at an Urban Medical University”; Ryan et al., “Breastfeeding Continues to Increase.” For more on the historical role of visiting nurses in lowering infant mortality and increasing breastfeeding rates, see Meckel, Save the Babies, 135–139; Wolf, Don’t Kill Your Baby, 105–111; Wolf, “Let Us Have More Mother-Fed Babies.”