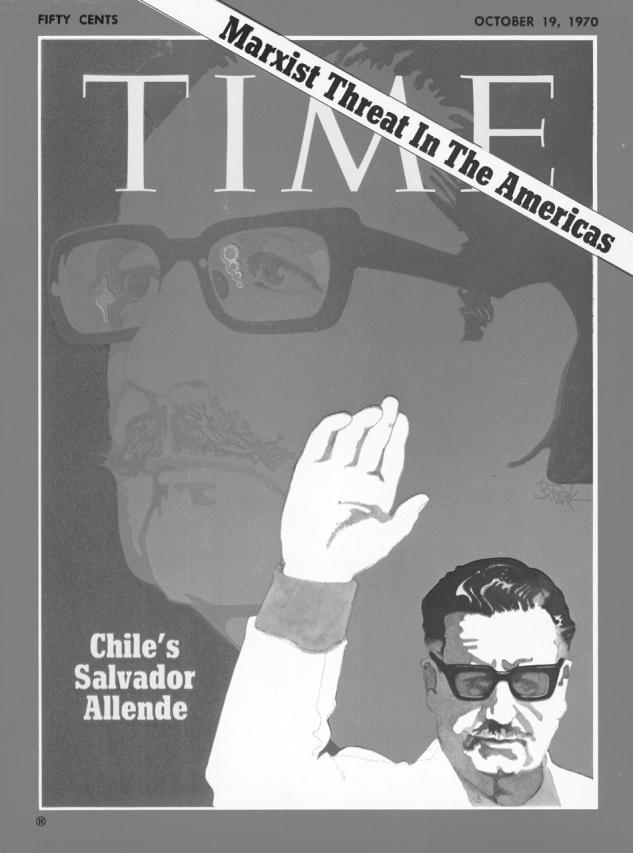

Figure 1.

BORN ON JULY 26, 1908, IN VALPARAISO, SALVADOR ALLENDE came from an upper-class Chilean family with a long history of political activism. His grandfather was one of the founders of the Chilean Radical Party in the 1860s, and his father and uncles were also Radical Party militants.1 After graduating from secondary school at the age of 16, Allende enrolled in the Coraceros Cavalry Regiment and, after a tour of duty, entered medical school at the University of Chile. Medical school helped further radicalize him as he lived, in very humble circumstances, with a group of students attracted to the writings of Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky. Allende became a student activist and was arrested twice and expelled once during his medical school years.2 He graduated in 1932 but, because of his radical history, was turned away from the Valparaiso hospitals and had a difficult time finding work as a physician. Allende was forced to take work as a pathology assistant, performing autopsies on the cadavers of the poor. He found the work dull, but it reinforced his dedication to social justice. He eventually established a practice among public welfare patients in Valparaiso.

In 1933, Allende was one of the founders of the Chilean Socialist Party, which was based on Marxist principles but was intended to be specifically Chilean rather than broadly international in its orientation and parliamentary rather than revolutionary in its politics. In 1937, he was elected as a Socialist deputy to the Chilean National Congress (the lower house), where he introduced legislation on public health, social welfare, and the rights of women. Two years later, Allende was named minister of health, prevention, and social assistance in the Popular Front government, a position he held until 1942.

In 1939, he published La Realidad Médico-Social Chilena (The Chilean Socio-Medical Reality), the source from which the excerpt published here in translation is taken (pages 195–198). Howard Waitzkin notes that this book “conceptualized illness as a disturbance of the individual fostered by deprived social conditions.”3(p75) It focused on specific health problems that were generated by the poor living conditions of the working class: maternal and infant mortality, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted and other communicable diseases, emotional disturbances, and occupational illness. He concluded the book with the Ministry of Health’s proposals for health improvement that emphasized social change rather than medical interventions: income distribution, a national housing program, and industrial reforms.

In 1942, Allende became the leader of the Chilean Socialist Party and in 1945 he was elected to the Senate (the upper house of parliament). During the 1950s, he introduced the legislation that created the Chilean national health service, the first program in the Americas to guarantee universal health care.4 Allende would remain in the Senate until 1970, and for nearly a decade during his tenure served as vice president and president of the Senate. He ran for president on 4 occasions: in 1952, 1958, 1964, and 1970. In the latter year, as head of the Unidad Popular coalition, he won 36.3% of the popular vote in a 3-way race. The Chilean Congress then chose him as president. Allende called for profound economic and social change focused on improving the condition of the poor and decreasing the role of private property and of foreign corporations.5 As president, he sponsored the decentralization of health care by empowering local health councils that worked with social service sectors to serve the impoverished masses. Chilean doctors often felt threatened by Allende’s health care policies, which focused on public rather than private care and thus meant less income for private physicians.

Other democratic nations, most notably the United States, found Allende’s brand of democracy intolerable and gave millions of dollars to his various opponents, including organized medicine. Factional divisions within the Unidad Popular and the Socialist Party, political opposition from the Chilean center and right, and economic instability all contributed to undermining Allende’s presidency.6 On September 11, 1973, his government fell to a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet. Allende was found dead that same day. While the Chilean government maintains that he committed suicide, many others claim that he was assassinated by Pinochet’s troops.

References

- 1.Lavretski J. Salvador Allende. Moscow, Russia: Editorial Progreso; 1978.

- 2.Debray R. Chilean Revolution: Conversations With Allende. New York, NY: Pantheon; 1972.

- 3.Waitzkin H. The Second Sickness: Contradictions of Capitalist Health Care. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1983.

- 4.Waitzkin H, Iriart C, Estrada A, Lamadrid S. Social medicine then and now: lessons from Latin America. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1592–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allende Gossens, Salvador (1908–1973), president of Chile (1970–1973). Available at: http://www.utm.utoronto.ca/~w3his290/A-Allende-biography.html. Accessed July 22, 2003.

- 6.Waitzkin H, Modell H. Medicine, socialism, and totalitarianism: lessons from Chile. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]