Abstract

Violence is the main public health problem in Colombia. Many theoretical and methodological approaches to solving this problem have been attempted from different disciplines. My past work has focused on homicide violence from the perspective of social medicine.

In this article I present the main conceptual and methodological aspects and the chief findings of my research over the past 15 years. Findings include a quantitative description of the current situation and the introduction of the category of explanatory contexts as a contribution to the study of Colombian violence.

The complexity and severity of this problem demand greater theoretical discussion, more plans for action and a faster transition between the two. Social medicine may make a growing contribution to this field.

Violence is not only a political, sociological, or military problem but also a public health problem. In Colombia, violence is in fact the primary public health problem. The high rates of homicide and kidnapping, the significant reduction in quality of life, and the systematic violation of international humanitarian rights (the group of international rules intended to limit wars and protect civilians) and the medical mission (the people, institutions, and actions dedicated to attending to the victims of national and international conflicts) are evidence of the enormous impact violence has on health in Colombia.

Various theoretical approaches have been proposed for the study of violence. These approaches have mainly emerged from the social sciences. In the health sector, epidemiology—with its different tendencies and its different approaches—has been the discipline most actively involved in the study of this problem. I present the conceptual bases and the principal findings and conclusions of my research in this topic, from the perspective of social medicine, over the past 15 years.

CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL BASES

The Concept of Violence

There is no accurate and universally accepted meaning for the concept of violence. There are many definitions, and each of them highlights specific aspects that are usually related to the author’s area of expertise. The World Health Organization, for instance, defines violence as

The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.1(p5)

Of course, while this definition includes the most essential elements of the concept, it includes particularities that are not necessary in a definition and excludes important elements of violence. I define violence, more concisely, as a specific form of human interaction in which force produces harm or injury to others to achieve a given purpose.

Given its implications, it is necessary to discuss the contents of this definition. The human character of violence implies that it is an intelligent activity. In this context, intelligent means it requires thinking and programming; it demands resources and has a purpose. Violence as a form of human interaction is a learned behavior. Although violent acts may initially appear to be irrational, they have an intrinsic logic and a context.

The most specific characteristic of violence is that it is a relationship based on the use of force. Force can be physical or psychological, and it can be applied directly or through an instrument. It also can be applied at different intensities and can generate different levels of damage, and its application in violent acts is usually asymmetrical.

Violence always produces harm or injury; without damage, there is no violence. Damage can be physical or psychological, and it also may occur in different levels of intensity.

Purpose is the most polemical characteristic of violence. It refers to the intention of achieving a particular goal, but it differs from the intention of producing harm. Violence is not a random event; it does not happen without a direction or interest that may or may not be conscious. Power is one of the most common purposes of violence. Power and violence are closely related,2 but they are very different concepts—while power is a goal, violence is an instrument. Those who analyze violence often refer to this as the instrumental nature of violence.2–4

As a consequence of its characteristics, it is clear that violence is a process and it has a historical nature. Violence is not a single action: it involves different steps, activities, and consequences for both the victim and the agent, and it affects individuals as well as their surroundings. Violence changes: its intensity and modalities vary among different countries and among different periods in time. This implies that violence can be reduced and modified and, therefore, some types of violence are susceptible to prevention.

Homicide as an Indicator of Violence

As a result of its serious consequences and a greater reliability in registry, homicide has long been recognized as one of the most important indicators of violence. In the case of Colombia’s current cycle of violence, homicide is undoubtedly the indicator that most clearly portrays the magnitude and the severity of the situation. With certain limitations, especially in those regions of the country that are under the control of illegal armed groups, it also is the best-documented form of violence. My research has involved the analysis and the confrontation of diverse and often variable sources of information on homicides.

What is an Explanatory Context?

In an effort to go beyond the descriptive level, while at the same time attempting to overcome the theoretical difficulties posed by the concept of cause, I have proposed the use of explanatory contexts as a useful theoretical tool for the study of violence in Columbia that can be extended to other areas of social research. An explanatory context is the specific combination of cultural, economic, social-political, and legal conditions that make a phenomenon historically possible and rationally understandable. In this way, an explanatory context provides for a description of the origin and an explanation of a phenomenon, but it avoids the blame and the determinism that are so often involved when using the concept of cause.

When studying a specific phenomenon, it is necessary to identify the different components of the explanatory context or, even better, the different explanatory contexts involved. It also is important to understand that while the phenomena being studied are still ongoing, explanatory contexts can and should be seen as provisional. Definitive explanatory contexts can be established only when dealing with events of the past.

Structural Conditions and Transitional Situations

While studying violence in Colombia within the framework of social medicine, I have found it methodologically useful to differentiate between structural conditions and transitional situations. Structural conditions are processes of longer duration that are related to the fundamental components of the phenomenon under study. Transitional situations, on the other hand, are processes of shorter duration that exert an important but complementary influence over the fundamental components. In the case of violence, this differentiation is useful when explaining the phenomenon and when seeking possible solutions.

The study of violence in Colombia has long involved a confrontation between structuralists and transitionalists. The former believe that without addressing fundamental and historically accumulated problems, such as inequality, impunity, and intolerance, symptomatic approaches make no sense. The latter, on the other hand, believe that all efforts should be focused on the solution of the more immediate problems, such as the armed conflict and illegal drug trafficking, assuming that structural problems have always been present and, therefore, do not account for the current situation of violence. This conflict of views has had a clear impact on Columbia’s policies and strategies toward violence. The social-medical approach attempts to study the ways in which structural and transitional elements interact, and it emphasizes the need for a solution strategy that integrates both dimensions. It avoids exclusions that initially appear to simplify the task but are usually ineffective in the long term.

The Theory–Fact–Discourse Approach

As another methodological contribution to the study of violence in Colombia from the social-medical perspective, I have implemented an approach that integrates 3 elements: the theoretical insight of different schools of thought, the factual data that arise from different sources, and the verbal or written testimony of the actors and victims involved. Although often attempted, approaches that isolate each of these 3 elements are insufficient for useful analysis of a problem so complex. The integration of these 3 elements is far more complex, but it offers a more thorough view of the situation and overcomes, at least in part, the problems of an overly theoretical or an overly subjective and emotional view and the many limitations of punctual descriptions offered by mass media.

QUANTITATIVE ASPECTS

Three aspects of Colombia’s current situation of violence are particularly outstanding: its generalization, its growing complexity, and its progressive degradation. The generalization of violence in Colombian violence refers to its expansion in time and space as well as its expansion in the number and the type of social settings it permeates. While the problem expands, its complexity increases continuously—the actors of violence are increasingly diverse. Individuals often switch from one group to the other, and the manifestations and the implications of violence are highly variable and rapidly evolving. The progressive degradation of violence in Colombia refers to the disregard of any ethical or humanitarian principles, including internationally accepted principles for situations of war. This degradation also covers the methods and the mechanisms of action, which include massacres (collective murders of unarmed individuals), kidnappings (sometimes collective and indiscriminate), and the destruction of entire towns. In the past few years, the annual homicide rate in Colombia has oscillated around 60 per 100 000 inhabitants; in 2000, the world’s average homicide rate was 8.8 per 100 000 inhabitants, which is about 7 times less than Colombia’s rate. Presently, Columbia’s homicide rate is the highest of any country in the world.

By far, the greatest impact of homicide violence in Colombia is on the male population. In 2001, males accounted for 92.5% of homicide victims; however, 2 worrisome facts should be noted. First, the percentage of female victims of homicide has been rising over the past 20 years. Second, despite a 1:12 ratio when compared with males, the actual number of female victims of homicide is extremely high. In 2001, the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences registered 1972 female victims of homicide, which is an average of 5 female victims per day.

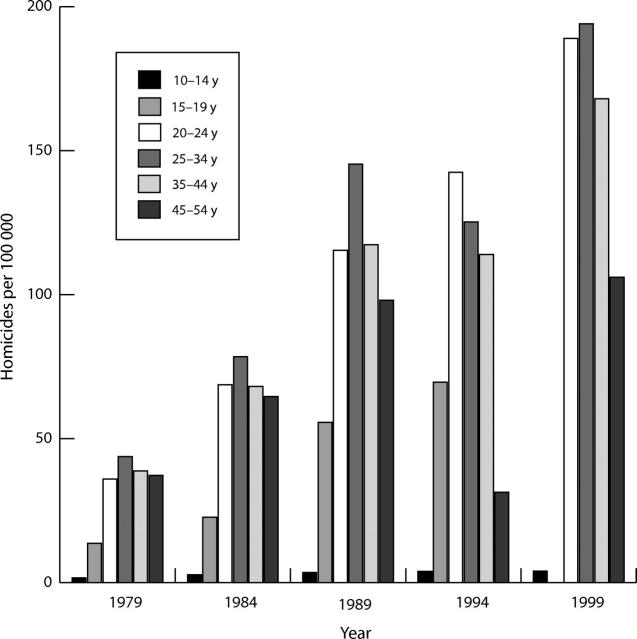

I found the distribution of male victims of homicide to show a significantly higher impact on young adult populations. Figure 1 ▶ shows the age distribution by 5-year periods from 1979 to 1999. Clearly, the highest rates are between ages 15 and 44 years. The rates for adolescents and young adults aged 25 to 34 years are alarming, especially in 1999, the last year included in the figure. During that year, the homicide rate for males aged 20 to 34 years was 3 times as high as the national average. The situation is even more dramatic when analyzed in terms of age and gender distribution by geographic location: in 2001, for example, the homicide rate for males aged 18 to 24 years in the Department of Antioquia was 728 per 100 000, an overwhelming fact that portrays the extreme severity of the problem.

FIGURE 1—

Rates of homicide victimization for males, by age category: Colombia, 1979–1999.

Note. Data not available for 15- to 19-year-olds for 1999.

The distribution of homicides among different regions of the country, which are administratively divided into departments, shows striking contrasts that can be helpful in defining the origin and the dynamics of the problem. Antioquia, a department whose capital is the city of Medellín, has persistently led the country in homicide rates and even tripled the national average in 1991. Antioquia has been a very important setting for the armed conflict as well as the problem of illegal drug trafficking. Interestingly, its homicide curve decreased immediately after the time when the infamous Medellín Cartel was most severely hit by the law enforcement authorities. In the Department of Valle, homicide rates began to increase as the rates in Antioquia began to decrease. Valle also has been an important setting for both the armed conflict and illegal drug trafficking, and an increase in drug-related activities was seen in Valle immediately after the Medellín Cartel was dismantled. The capital city of Bogotá has maintained rates below the national average, and from 1993 on, it has shown a steady decrease that coincides with the local authorities’ implementation of a number of programs for violence prevention and peaceful social interaction.

This regional distribution of homicide violence shows recent changes. Antioquia left the top of the homicide list in 2001, when it was replaced by 2 other regions—Guaviare and Putumayo—where a significant increase in both the armed conflict and illegal drug production and commercialization has been evident during the past few years.

EXPLANATORY CONTEXTS

On the basis of the current state of research and a continuous observation of the situation, I have proposed 4 explanatory contexts of violence in Colombia: political, economic, cultural, and legal.5 I conducted a field study and asked a population of victims and actors of violence in Colombia to assign each of these 4 contexts a relative weight in terms of each context’s ability to explain the problem.

Political Explanatory Context

The study participants assigned the greatest importance to this context, which includes 4 main aspects: the role of the government, the persistence of the political–military conflict, intolerance, and the role of society as a whole. The first aspect has to do with corruption, a progressive decay in the legitimacy and the reliability of the government—its increasing weakness and slow dissolution6 and its relative absence from different regions and different aspects of national life, which are fostered by the imposition of the neoliberal model.

The political–military conflict has a long and complicated history. The conflict’s roots can be traced to the period of exacerbated violence during the mid-20th century,7,8 and its activation occurred between the mid-1960s and the early 1970s.9 The conflict began as a military confrontation between extreme left-wing guerrilla groups and the government. In the early 1980s, a new actor appeared: the paramilitary organizations10 that began as self-defense groups led by drug lords and landlords who were determined to take the war against the guerrilla groups in their own hands and who were often supported by certain sectors of the government’s military. Illegal drug trafficking has significantly permeated the conflict, and the armed groups involved in the conflict have sustained variable and ambiguous links with the organizations that control drug trafficking. The strong, multinational economic interests involved in gun trade also have been a permanent stimulus for Colombia’s armed conflict.11

Over the past 2 decades, the conflict has worsened, and the illegal armed organizations have increased their military power and their geographic control. During the same period, several attempts to reach a negotiated solution have failed, including the development of a new constitution in 1991.12 The participation of the international community has been minimal.

Political intolerance—the inability to solve ideological and political differences in a nonviolent manner—has been a continuous trend in Colombian affairs. The armed conflict expresses and continuously feeds a high level of intolerance that has led to the extinction of a number of unarmed alternative political groups. It also has led to the reduction of politics, which has resulted in either biased elections or military confrontation. Not every homicidal action can be attributed to political and social intolerance, but as many as 20% of them can.5 Although political intolerance is usually linked to the armed conflict, it becomes a pattern that is easily incorporated into other areas of social interaction.

Two important components of the political explanatory context are social apathy toward violence and precarious levels of organization and participation to confront the problem. Despite its intensity, persistence, and generalization, Colombian society has shown little in the way of a clear and consistent position toward violence. The responsibilities and possibilities of the international community also are increasingly recognized.13

Economic Explanatory Context

The fundamental aspect of the economic context is the structural inequality of Colombian society. Colombia is a good example of the fact that there is no unidirectional relationship between poverty and violence. It also is a good example of the fact that inequality and violence are strongly related. This relationship has been demonstrated at an international level by the World Bank in a study conducted between 1970 and 1994 in different regions of the world.14 Inequality in the distribution of resources and opportunities has progressively increased in Colombia.15 Some data may be helpful in understanding the situation: 60% of Colombia’s population lives in poverty, and 23% live in extreme poverty; 3.3 million Colombians are unemployed, and informal labor accounts for 61% of those employed; 37% of those who work earn less than the minimal salary; and 48.6% of the population is not covered by any type of social security.16

The trafficking of illegal drugs to the numerous consumers in first-world nations, which was commonly perceived in the mid-1970s as a path toward a more even distribution of wealth in Colombia, has worsened the concentration of rural property and other resources and has increased the levels of inequality and, thereby, the levels of violence.17,18

Cultural Explanatory Context

This is possibly the least studied of the explanatory contexts in both Colombian and international studies of violence. Violence is human, historical, and social and, therefore, is clearly immersed in the realm of culture. In the case of Colombia, this context has 3 main aspects. The first refers to ethics, which are still at the core of all matters related to violence. There is a gap between social values and current problems, especially violence. Even the primacy of life as a value is commonly underestimated or ignored.19 The second aspect refers to education. It includes both the extent of coverage and the contents of Columbia’s public education system: 83% of the Colombian population has access to primary education, 63% has access to secondary education, and only 15% has access to higher (professional) education. There is a clear discrimination against the poorer populations.16 The third aspect refers to the psychological components of the origins and the dynamics of violence. It involves the chronic accumulation of feelings of hatred and revenge between individuals and groups. It also includes the individual and collective psychopathologies behind certain forms of cruelty and the behavior of some paid murderers.

Legal Context

This context is closely linked to the political and cultural contexts of violence and involves 2 main aspects: the inadequacy of the country’s legal structure with respect to the type and magnitude of present-day violence, and the inefficiency of the penal system. Its clearest indicator is impunity, which has worsened over the past 4 decades. According to official estimates, “While the probability of charges for a crime in the mid-1960s was 20%, this number was down to 5% in 1971 and has decreased continuously since to the current 0.5%.”20 According to the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences, 75% of homicides in 199921 and 89% of homicides in 2001 had unknown actors There is an inverse relationship between the criminal and the penal abilities of modern Colombian society. As homicide rates increase, the capture and conviction of murderers decreases. This also exposes the positive feedback between impunity and violence in Colombia’s current situation of violence.

CONCLUSIONS

Many conclusions can be drawn from this research, but there are 3 that are particularly important. The first is that homicide violence in Colombia is a severe and complex process. Colombia is a country with slightly over 40 000 000 inhabitants, and homicide rates remain above 60 per 100 000. More than 500 000 people have been murdered in the past 27 years alone. The factors that generate violence in Colombia interlink—new actors appear and combine—and the conflicts of interest that are involved are increasingly strong. Violence in Columbia deserves a greater degree of attention from Colombian society, its government, and the international community.

Secondly, the social-medical approach to Colombian violence has both possibilities and limitations. With such a complex problem, any single discipline, theory, or methodological approach can be expected to be insufficient. The social-medical approach offers the combination of careful and permanent observation, the introduction of new analytic categories and methodological resources, and the generation of integrative and consistent data. The limitations of the social-medical approach in this setting include the difficulty—and sometimes risk—of accessing valuable information on violence in Colombia, the lack of specific indicators for certain facts and processes, the budding nature of some of the concepts and methods that are being implemented, and the number—still small—of researchers using the approach and the irregularity of communication among them.

Finally, the intensity of violence in Colombia requires a faster transition between theoretical discussions and plans for action. There appears to be agreement on the idea that intellectuals and academicians should participate in the descriptive and analytic study of the problems, the formulation of feasible proposals for action, and the effective support of the transitional phase between theory and social conscience. Social medicine may—and should—make a growing contribution to this effort.

Acknowledgments

This article was translated from the original Spanish by Luis Franco, MD.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002.

- 2.Arendt H. On Violence. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1970.

- 3.Benjamin W. For a Critic of Violence. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Editorial Leviatán; 1995.

- 4.Cortina A. Hasta un Pueblo de Demonios: Ética Pública y Sociedad. Madrid, Spain: Editorial Taurus; 1998.

- 5.Franco S. El Quinto, No Matar: Contextos Explicativos de la Violencia en Colombia. Bogotá, Columbia: Institato de Estudios Politicos y Relaciones Internacionales–Tercer Mundo Editores; 1999.

- 6.Pecault D. De las violencias a la violencia. In: Sánchez G, Peñaranda R, eds. Pasado y Presente de la Violencia en Colombia. 2nd ed. Santafé de Bogotá, Columbia: Institato de Estudios Politicos y Relaciones Internacionales–Centro de Estudios Regionales de Colombia; 1995.

- 7.Guzmán G, Fals-Borda O, Umaña E. La Violencia en Colombia. 9th ed. Bogotá, Columbia: Carlos Valencia Editores; 1980.

- 8.Oquist P. Violencia, Conflicto y Política en Colombia. Bogotá, Columbia: Instituto de Estudios Colombianos; 1978.

- 9.Sánchez G, Peñaranda R, eds. Pasado y Presente de la Violencia en Colombia. 2nd ed. Santafé de Bogotá, Columbia: IEPRI–CEREC; 1995.

- 10.Medina C. Autodefensas, Paramilitares y Narcotráfico en Colombia. Santafé de Bogotá, Columbia: Documentos Periodísticos; 1990.

- 11.Tokatlian JG, Ramírez JL, eds. La Violencia de las Armas en Colombia. Santafé de Bogotá, Columbia: Tercer Mundo Editores; 1995.

- 12.Valencia GA. Violencia en Colombia y Reforma Constitucional, Santiago de Cali, Columbia: Editorial Universidad del Valle; 1998.

- 13.Franco S. International dimensions of Colombian violence. Int J Health Serv. 2000;30(1):163–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fajnzylber P, Lederman D, Loayza N. What Causes Crime and Violence? Washington, DC: The World Bank; 1997.

- 15.Fresneda O, Sarmiento L, Muñoz M. Pobreza, Violencia y Desigualdad: Retos para la Nueva Colombia. Santafé de Bogotá, Columbia: United Nations Development Programme; 1991.

- 16.Contraloría General de la Nación (Colombia). La Exclusión Social en la Sociedad Colombiana. Bogotá, Columbia: Contraloría; 2002.

- 17.Deas M, Gaitán F. Dos Ensayos Especulativos sobre la Violencia en Colombia. Santafé de Bogotá, Columbia: Tercer Mundo Editores; 1995.

- 18.Uprimny R. Narcotráfico, régimen político, violencias y derechos humanos en Colombia. In: Vargas R, ed. Drogas, Poder y Región en Colombia. 2nd ed. Santafé de Bogotá, Columbia: Cinep; 1995:59–146.

- 19.De Currea-Lugo V. Derecho Internacional Humanitario y Sector Salud: El Caso Colombiano. Bogotá, Columbia: Red Cross International Committee–Plaza y Janés Editores; 1999.

- 20.Comisión de Racionalización del Gasto y las Finanzas Públicas. El Saneamiento Fiscal, un Compromiso de la Sociedad, Tema V. Final report. Santafé de Bogotá, Columbia: República de Colombia; 1997.

- 21.Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (Colombia). Forensis 1999. Bogotá, Columbia: The Institute; 2000.