Abstract

Objectives. This study examined preventive care delivered in Manitoba during the 1990s by 3 different methods —childhood immunizations (by physicians and public health nurses under a government program), screening mammography (through a government program introduced in 1995), and cervical cancer screening (no program).

Methods. Longitudinal administrative data, an immunization monitoring system, and Canadian census databases were used.

Results. Cervical cancer screening rates remained static and showed strong socioeconomic differences; childhood immunization rates remained high with small socioeconomic gradients. The introduction of the Manitoba Breast Screening Program resulted in rising rates of screening and vanishing socioeconomic gradients.

Conclusions. Manitoba government programs in childhood immunization and screening mammography actively helped the provision of preventive care. Organized programs that target population groups, recognize barriers to access, and facilitate self-evaluation are critical for equitable delivery.

Researchers have recently started to examine the considerable effect of socioeconomic status on the utilization of preventive care. For example, the higher a woman’s education or income level, the more likely she is to receive a mammogram and a Papanicolaou test.1,2 These socioeconomic disparities in utilization are of particular concern given that the gradients in morbidity and mortality generally run in the opposite direction.3,4 Unfortunately, the lifting of financial barriers has not been enough to ensure high rates of preventive service use.5,6 In 1990, despite universal insurance coverage in Canada, socioeconomic disparities in mammography and Papanicolaou test use were similar for women in the province of Ontario and in the United States.1 Although in Canada screening rates for these 2 tests have increased relative to those in the United States, disparities across socioeconomic strata have persisted and were similar in both countries in the mid-1990s.7,8

Individuals of higher socioeconomic status appear to have the resources both to avoid emerging risks and to take advantage of new protective factors. Differences in knowledge, resources, and attitudes across socioeconomic levels contribute to the formation of socioeconomic disparities in the utilization of new types of preventive care.2,9 This process tends to increase already-significant disparities in health status between population subgroups.9–11

Within the framework of national health insurance, is it possible to design and implement preventive care in order to minimize socioeconomic disparities in utilization? Differences in knowledge and resources have their largest effects when the health care system is passive, that is, when accessing preventive care is the sole responsibility of the individual. Merely lifting financial barriers does not effect a shift in responsibility away from the individual and consequently may not have a major impact on differential use by various population groups. In contrast, active systems–preventive care programs in which society assumes part of the burden of activity for prevention and early detection–hold the potential to increase population coverage rates and minimize socioeconomic disparities.2,7,12–14 Unlike passive screening, an active program includes recruitment, recall and follow-up, quality assurance and quality control, and evaluation of program performance and outcomes.

Building on earlier work, this study examined the long-term effects of the ongoing mammography screening program on population coverage and socioeconomic disparities in Manitoba.15 Changes in the delivery of mammography in the 1990s provided an opportunity to consider the effect of targeted delivery programs on the utilization of preventive care. Because no changes occurred in the organization of childhood immunization or Papanicolaou testing during the study period, longitudinal information on those services could be used for comparison with the mammography data. Thus, we were able to highlight factors that could lead to effective delivery of preventive care.

ORGANIZATION OF CARE

Screening Mammography

The goal of Canadian breast screening programs is to reduce morbidity and mortality without adversely affecting the health status of those who participate in screening. Toward achieving this goal, population-based breast screening programs call for 70% of women aged 50 to 69 years to be screened every 2 years.16 Until the Manitoba Breast Screening Program (administered by CancerCare Manitoba and funded by Manitoba Health) began in mid-1995, radiologists delivered mammography screening on a fee-for-service basis in 3 urban centers. By the fall of 1996, arrangements were complete for all screening for women aged 50 to 69 years to be delivered through the provincial program. As in the past, diagnostic mammography continues to be performed by radiologists. A small amount of hospital-based bilateral mammography continues that cannot be definitively categorized as screening or diagnostic.

Through the program, 3 permanent facilities serve the urban populations of Winnipeg (the capital of the province), Brandon, and Thompson. Mobile screening mammography vans are sent to rural regions, returning annually to larger communities and biennially to smaller communities. Approximately 50 communities are reached every year. Mobile vans also target certain neighborhoods within Winnipeg with traditionally low rates of mammography. Six weeks before the arrival of a mobile van, letters are sent to eligible women inviting them to attend the program. Three to 4 weeks later, follow-up letters are sent to those women who have not yet made appointments. The media, public health officers, and community centers are also used to advertise the arrival of the van.17

Childhood Immunizations

The goal of the Manitoba childhood immunization program is to ensure complete, timely immunization of all children in the province according to the recommended schedule. The schedule for the first year of life is 3 diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus immunizations, 3 Haemophilus influenza type b vaccines, and 2 oral polio vaccines, or appropriate alternatives. In the second year of life, 1 diphtheria–pertussis–tetanus immunization, 1 Haemophilus influenza type b vaccine, 1 oral polio booster, and 1 measles–mumps–rubella vaccination should be administered. Three levels of government—municipal, provincial, and federal—and 2 types of providers—physicians and public health nurses—are involved in the delivery of immunizations.15

The Manitoba Immunization Monitoring System (MIMS), a population-based information system, provides monitoring and reminders to help achieve high levels of immunization.18 Immunization status is monitored by comparing the system record and the recommended schedule in the month of the first, second, fifth, and sixth birthdays.18 Detection of missing or incorrectly coded immunizations prompts a letter to the family or the provider requesting correction or completion. “Reminders” are distributed through public health offices, with amended records returned for data entry. Children whose records remain incomplete are actively followed by these offices and offered immunizations.

Cervical Cancer Screening

The recommendation from the 1989 Canadian National Workshop on Screening for Cancer of the Cervix was to screen women aged 18 to 69 years every 3 years where an organized screening program exists.19 The most significant additional recommendation involved conducting 2 Papanicolaou smears a year apart, when results were normal, for young women having their initial screening. At the time of the study, cervical cancer screening in Manitoba was carried out by physicians and approved laboratories; a provincial program was not implemented until 2001.

METHODS

Sources of Data

For administration of the provincial health insurance plan, Manitoba Health maintains a computerized population registry in which each individual has a unique personal health identification number. Physician claims and provincial program data build on this registry. The registry includes virtually the entire population and contains, for each individual, information such as unique identification number, postal code of residence, date of enrollment with Manitoba Health (birth or immigration) and date of enrollment termination (death or out-migration).

The Population Health Research Data Repository developed by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy from “snapshot” provincial population registries permits tracking of individuals with scrambled personal identification numbers for as long as they reside in Manitoba (since 1970). The administrative databases have been shown to be both reliable and valid for studies examining health and health care use.20–22 Incorporating registry information in the numerators and denominators has facilitated sensitivity testing of rate calculations.23

According to administrative data, coverage rates for mammography and Papanicolaou test use are 10% to 15% lower than corresponding rates in studies using survey data.24–26 Although surveys may capture preventive care use for which the provider did not submit a claim for entry into the administrative database, they cannot distinguish between diagnostic and screening mammography.27 Survey respondents also may telescope their experience into the time frame of interest.

Income Quintiles

Following previously established guidelines,28 urban and rural enumeration areas were independently ranked from poorest to wealthiest based on mean household income from 1991 and 1996 Canadian census public use databases. All Manitoba enumeration areas were grouped into 2 sets of 5 population quintiles, each containing approximately 20% of the urban or rural population. Residential postal or municipal codes were used to assign each resident to an enumeration area and thus to an income quintile (with Q1 being the lowest). When registered First Nations were treated separately because of the difficulty in obtaining accurate data, the number of cases in the rural lower-income quintiles decreased markedly.

Income quintiles for the Manitoba population for 1992 and 1993 were developed from the 1991 Canadian census, whereas those for 1994 through 1999 were based on the 1996 Canadian census. Manitoba areas tend to be classified in the same income quintile over time; the 1991–1996 interquintile correlations were 0.83 for urban areas and 0.68 for rural areas. Switching from the 1991 classification (used in 1993) to the 1996 classification (used in 1994) caused a slight discontinuity (6%) for immunization rates but not for mammography or cervical cancer screening rates. When the 1991 classification with the 1993 birth cohort was used, the result was a 6% higher immunization rate, for example, for the rural Q1 than the rate based on the 1996 classification. For the immunization analyses, the 1993 birth cohort was classified according to the 1996 quintiles because schedules were examined for 2 years after birth (1993 birth cohort rates represent data through 1995). Similar discontinuities were not observed for the mammography or cervical cancer screening data.

A population density rule was used to define urban and rural areas. The category urban includes those areas with a density of 400 or more persons per square kilometer and a concentration of 1000 or more persons.”29 All other areas are designated rural.

Socioeconomic disparities are reported by calculating the Q1/Q5 ratio—the use of preventive care in the lowest income quintile divided by the use of preventive care in the highest income quintile. Q1/Q5 ratios closer to 1 indicate greater congruency between rates for lower-income groups and higher-income groups. Utilization gradients found across these area income quintiles were similar to those found when using individual-level data on household income.30

Screening Mammography

Before 1995, mammography was entered twice into the database, once as a physician claim and once as a laboratory bill. The presence of scrambled personal health identification numbers on each claim provides checks to prevent double counting. Mammography carried out under the auspices of the Manitoba Breast Screening Program is now entered once with a special code. The limited numbers of hospital mammograms are billed by the physicians involved and recorded in available administrative data. To eliminate diagnostic mammography, only codes for bilateral mammography were retained for the analyses.

Childhood Immunizations

Regardless of provider, all immunizations given to registrants born on or after January 1, 1980, are required to be recorded in the MIMS. The MIMS file includes registry data, a code that identifies the vaccine administered and its sequence in the immunization schedule, and the service date. Provider identifiers distinguish between physicians and public health nurses. Comparisons between physician and MIMS records have shown high data quality for the nonaboriginal population.18

Cervical Cancer Screening

Information on Papanicolaou testing is normally entered into the provincial data twice, once as a physician claim and once as a laboratory bill. Physician claims capture an estimated 95% of such tests in Manitoba, excluding registered First Nations women.15,31

Approximately 40% of all Papanicolaou tests in Manitoba are analyzed at a single hospital-based, globally funded laboratory. During the period of this study, no laboratory claims were submitted for these tests; approximately 50% more physician claims than laboratory bills for Papanicolaou testing were generated in each year. Salaried nurses often conduct the test in northern areas that primarily service the aboriginal population; no physician claims are submitted for these tests, and a nonbilling laboratory is typically used.

First Nations Coverage

A lack of monitoring capabilities is a major problem among First Nations populations.15,32 Low levels of immunizations among First Nations reserves may reflect reality or an underreport of immunizations by federally employed nurses because of low numbers of MIMS terminals. In addition, federal and provincial records show quite different numbers of registered First Nations people, although efforts are under way to reconcile these differences. The Manitoba registry shows approximately 68,000 individuals as registered First Nations, whereas the federal Department of Indian and Northern Affairs shows 90 000.33 No marked change in relationships was found when the 2 classification schemes were compared.

Analysis

SAS (Version 8.01 for Unix 1999–2000; SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all data analysis and statistical testing. Cochran–Armitage tests for trend34 were used to examine changes in coverage rates over time, and the Fisher exact test was used to compare coverage rates among different groups at 1 point in time. We used linear regression to examine trends in Q1/Q5 ratios over time, and we compared Q1/Q5 ratios among different subgroups using the χ2 test for homogeneity of rate ratios across strata.35 To account for multiple significance tests, we used the Bonferroni method to adjust the α level to .005.

RESULTS

Screening Mammography

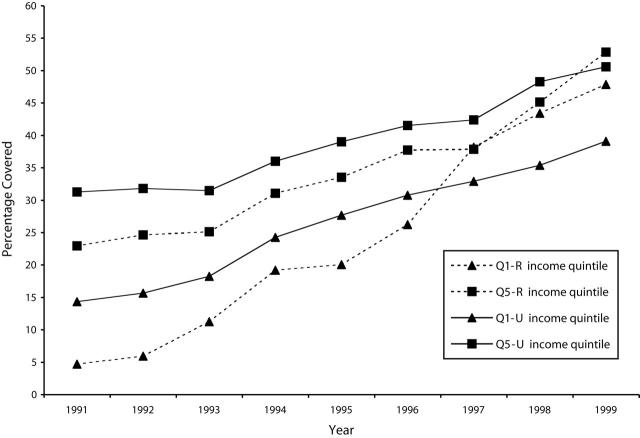

Figure 1 ▶ presents the coverage rates for women aged 50 to 69 years who reported having received 1 screening mammography within the past 2 years, in accordance with the recommended guidelines. Both rural and urban screening rates increased dramatically during the study period (P < .0001). Overall rural coverage rose from 12.6% in 1991 to 52.7% in 1999; during the same period, overall urban coverage increased from 22.6% to 46.9%.

Figure 1—

Percentage of Women Aged 50 to 69 Years With 1 Screening Mammogram in 2 Years: Manitoba, 1990s.

Note. Q1-R = lowest income quintile, rural; Q5-R = highest income quintile, rural; Q1-U = lowest quintile, urban; Q5-U = highest quintile, urban.

Between 1991 and 1996, coverage rates were significantly lower for rural women in less affluent areas (Q1-R) than for their urban counterparts (Q1-U) (P < .0001). In 1997, with the full implementation of the Manitoba Breast Screening Program, coverage rates for the rural poor surpassed those for the urban poor (P < .0001); by 1999, coverage for the rural poor reached 47.9% compared with 39.1% for the urban poor (P < .0001). A similar trend was observed among the more affluent rural women (Q5-R), although their coverage rates did not overtake those of the urban affluent (Q5-U) until 1999—52.8% versus 50.6% (P < .0001).

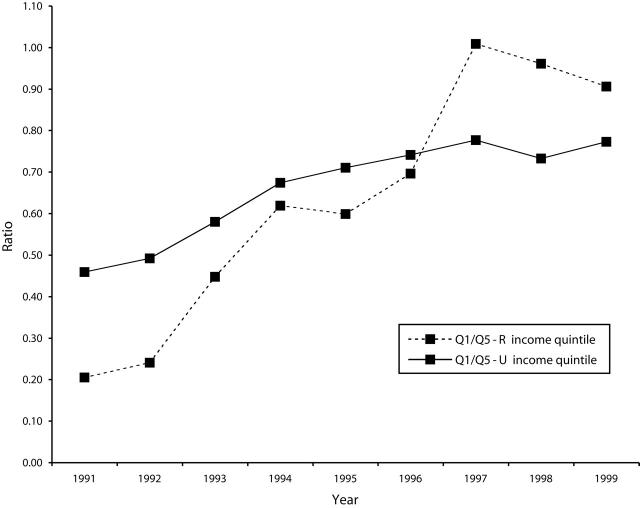

Over the study period, the corresponding Q1/Q5 ratios for both rural and urban women moved dramatically toward 1, reflecting the the more equal use of screening mammography among residents of relatively rich and relatively poor areas (P < .001) (Figure 2 ▶). In the 1991–1993 period, the urban Q1/Q5 ratio was higher (more equitable) than that of the rural population (P < .0001). By 1997, the rural Q1/Q5 ratio had jumped sharply, surpassing the urban ratio: ratios were 0.91 for rural women and 0.77 for their urban counterparts by 1999 (P < .0001).

Figure 2—

Q1/Q5 Ratio for Women Aged 50 to 69 Years With 1 Screening Mammogram in 2 Years: Manitoba, 1990s.

Note. Q1 = lowest income quintile, Q5 = highest income quintile.

Childhood Immunizations

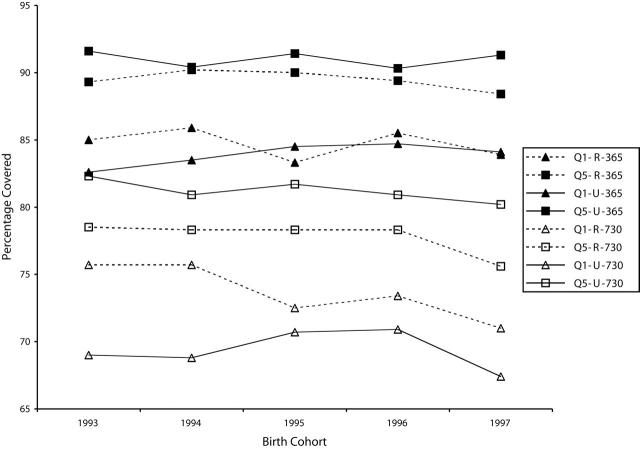

Figure 3 ▶ presents the percentage of successive cohorts for which immunization schedules were successfully completed by 365 and 730 days after birth. No significant trends over time were found for urban or rural children. A substantial portion of rural children (about 60% in the poorest areas) received their immunizations from public health nurses. Rates for successful completion of the immunization schedule during the second year of life were significantly lower than rates for the first year of life with stronger socioeconomic disparities. This may be partially due to recent media focus on concerns surrounding the safety of the measles–mumps–rubella vaccine36–38 or to delays in immunization delivery, given that rates of immunization completion at 7 years of age were higher than those at 2 years.39

Figure 3—

Percentage of Children With Completed Immunization Schedules 365 and 730 Days After Birth: Manitoba, 1990s.

Note. Q1-R = lowest income quintile, rural; Q5-R = highest income quintile, rural; Q1-U = lowest quintile, urban; Q5-U = highest quintile, urban.

At 365 days, no difference was found between rural and urban children, regardless of income quintile. At 730 days, Q1 children showed the only significant difference; those from rural areas experienced higher immunization rates than their urban counterparts in 1993 (75.7% vs 69.0%; P < .005) and 1994 (75.7% vs 68.8%; P < .005).

The Q1/Q5 ratio for successful completion of immunization schedules fluctuated between 0.90 and 0.96 at 365 days and between 0.84 and 0.97 at 730 days. At 365 days, rural and urban Q1/Q5 ratios were not significantly different. At 730 days, the rural rate exceeded the urban rate only in 1993 (0.96 vs 0.84; P < .005) and 1994 (0.97 vs 0.85; P < .005).

Cervical Cancer Screening

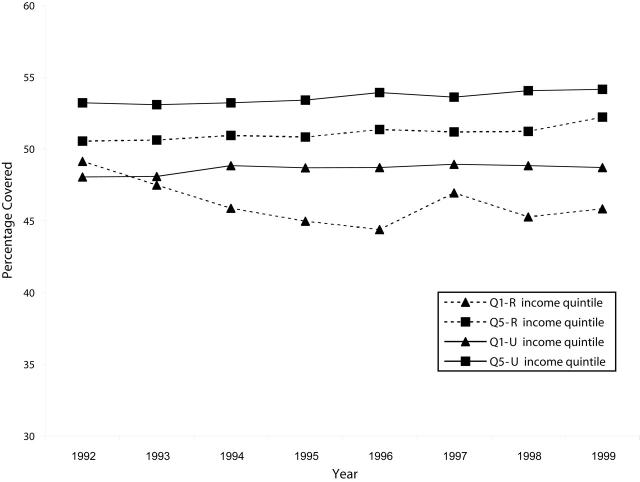

The percentage of women aged 18 to 69 years who had received 1 or 2 screening Papanicolaou tests within the past 3 years changed little over the study period (Figure 4 ▶). Coverage rates for both urban and rural women remained close to 50%, with urban rates slightly higher among all income groups (P < .0001 for Q5, P < .001 for Q1 after 1993).

Figure 4—

Percentage of Women Aged 18 to 69 Years With 1 or 2 Papanicolaou Tests in 3 Years: Manitoba, 1990s.

Note. Q1-R = lowest income quintile, rural; Q5-R = highest income quintile, rural; Q1-U = lowest quintile, urban; Q5-U = highest quintile, urban.

The corresponding Q1/Q5 ratio showed no trend among urban or rural women. Rural ratios fluctuated between 0.86 and 0.97, whereas urban ratios remained between 0.90 and 0.92. Comparisons of rural and urban Q1/Q5 ratios yielded mixed results, primarily due to fluctuations in the rate for rural poor over time.

First Nations Coverage

Although the First Nations data on cervical cancer screening did not permit analysis, some information on the other 2 programs was available.

Among the 1993–1997 birth cohort identified by Manitoba Health as registered First Nations, 55% of rural children (n = 6853) and 63% of urban children (n = 2984) were noted as having completed their first-year immunization schedules. Similar results were obtained when a slightly shorter time period (1994–1997) and the federal registered First Nations definition was used. Several tribal councils and provincial health regions showed particularly low rates of immunization schedule completion.

Although increasing, screening mammography rates among First Nations women aged 50 to 69 years were approximately half those of other Manitoba women. Just 24% of First Nations women in this age group had at least 1 bilateral mammogram in 1997 and 1998; results obtained with both definitions were very similar. Considerable variation by tribal council and health region was reported.

DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated the effect of shifting the burden of activity away from the individual to an organized provincial program. Cervical cancer screening within Manitoba, a completely passive and opportunistic method of delivery, showed static population coverage rates. Socioeconomic differences remained strong and, within the rural population, widened slightly. The persistence of these disparities is mirrored across Canada, where organized and comprehensive programs for cervical cancer screening have not yet been fully implemented.7,12,25,26,40 In contrast, childhood immunization rates during the first year of life have remained high with very small socioeconomic disparities. The active measures employed by MIMS (sending out reminders to health providers and parents and actively tracking down children with incomplete schedules) have increased coverage in many settings, both within Canada and beyond.41–44

Similarly, the introduction of the Manitoba Breast Screening Program, with its active recruitment strategies, has had a dramatic effect. Coverage rates rose more rapidly, whereas long-running differences in use vanished. Rural women surpassed their urban counterparts in screening rates, and the rural Q1/Q5 ratio stabilized near 1. Organized mammography programs have increased population coverage in other Canadian provinces, although their effect on socioeconomic disparities in coverage has not yet been fully explored.27,45

To be successful, a program of prevention or early detection must recognize that vulnerable individuals, regions, and subgroups differ–not only from the rest of the population but also from one another–in the barriers they encounter in accessing preventive care.12 Strategies such as lowering the suggested screening frequency in the hopes of increasing population coverage are likely to fail unless these barriers are addressed.43,46

The Manitoba Breast Screening Program has significantly improved access to screening. Mobile vans have helped lower the transportation and distance barriers facing rural residents of all economic levels but have not been as effective for the urban poor (Figures 1 ▶ and 2 ▶). Opportunity costs in terms of time spent seeking health care, high residential mobility, and lack of continuity of care, as well as cultural and knowledge barriers, may play a more significant role in urban settings, requiring different strategies.47–50

Finally, a successful organized program for delivering preventive care must be able to identify groups at particularly high risk and to monitor the success of interventions in reaching these high-risk groups. This requires a well-integrated and confidential information technology system able to manage both notification and follow-up.13,14,51 These qualities have already been recommended for tracking immunization coverage44 and are embodied in MIMS. This system works even though both fee-for-service physicians and public health nurses deliver the immunizations.

Population-based information has allowed identification of the particularly vulnerable urban poor, a high-risk group missed in studies emphasizing the risk of rural residence in mammography use.5,24 The Manitoba Breast Screening Program has undergone a self-evaluation to examine differences in satisfaction by screening location and screening result.17 The program has tried to customize its outreach efforts by developing key contacts, working through English-as-Second-Language classes, involving community committees in selection of sites (for the mobile van), and providing rapid feedback about participation rates and cancer detection.

Gaps in data limit monitoring capabilities for First Nations populations, which tend to have high overall morbidity.32,52 Efforts are being made to obtain better data and to improve feedback to First Nations about their uptake of preventive services.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests guidelines for developing future programs. To reach both advantaged and disadvantaged portions of a population, a program should shoulder the burden of activity and not rely on opportunistic methods. The program must also recognize different barriers to access and be capable of self-evaluation. This is best accomplished when the preventive program is organized under a single authority.

Since 2001, a Manitoba program targeting cervical cancer screening has been under way. All laboratories that process Papanicolaou smears are required to provide individual claims and reports to the provincial screening program, which can now identify individuals, regions, and subpopulations (including First Nations) at risk. This is facilitating identification of specific barriers and initiation of interventions through educational and media campaigns. The success of the Manitoba Breast Screening Program and MIMS suggests that this new effort will be successful in increasing population coverage rates and minimize socioeconomic disparities in Papanicolaou screening.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Canadian Population Health Initiative, the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, and the Department of Health of the Province of Manitoba under a contract with the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy.

The authors acknowledge the St Boniface General Hospital Research Centre and are indebted to Health Information Services, Manitoba Health, for the provision of data. Special thanks to Marion Harrison, Kathleen Decker, and Donna Turner for their comments on the manuscript and to Jo-Anne Baribeau for manuscript preparation.

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the health research ethics board of the University of Manitoba, Bannatyne Campus.

Contributors S. Gupta and L. L. Roos contributed substantially to the conception of the study, the interpretation of the data, and the drafting of the article. R. Walld, D. Traverse, and M. Dahl contributed substantially to the analysis of the data and the revision of the content.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Maxwell CJ, Kozak JF, Desjardins-Denault SD, Parboosingh J. Factors important in promoting mammography screening among Canadian women. Can J Public Health. 1997;88:346–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz SJ, Hofer TP. Socioeconomic disparities in preventive care persist despite universal coverage: breast and cervical cancer screening in Ontario and the United Kingdom. JAMA. 1994;272:530–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorey KM, Holowaty EJ, Laukkanen E, Fehringer G, Richter NL. Association between socioeconomic status and cancer incidence in Toronto, Ontario: possible confounding of cancer mortality by incidence and survival. Cancer Prev Control. 1998;2:236–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billings J, Zeitel L, Lukomnik J, Carey TS, Blank AE, Newman L. Datawatch: impact of socioeconomic status on hospital use in New York City. Health Aff (Millwood). 1993;12:162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lantz PM, Weigers ME, House JS. Education and income differentials in breast and cervical cancer screening: policy implications for rural women. Med Care. 1997;35:219–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenyon TA, Matuck MA, Stroh G. Persistent low immunization coverage among inner-city preschool children despite access to free vaccine. Pediatrics. 1998;101:612–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snider J, Beauvais JE, Levy I, Villeneuve P, Pennock J. Trends in mammography and Pap smear utilization in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 1996;17:108–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz SJ, Zemencuk JK, Hofer TP. Breast cancer screening in the United States and Canada, 1994: socioeconomic disparities persist. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:799–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Link BG, Northridge ME, Phelan JC, Ganz ML. Social epidemiology and the fundamental cause concept: on the structuring of effective cancer screens by socioeconomic status. Milbank Q. 1998;76:375–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- 11.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S, Frankel S. How policy informs the evidence. “Evidence based” thinking can lead to debased policy making. BMJ. 2001;322:184–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grunfeld E. Cervical cancer: screening hard-to-reach groups. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;157:543–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paquette D, Snider J, Bouchard F, et al. Performance of screening mammography in organized programs in Canada in 1996. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;163:1133–1138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller AB. Organized breast cancer screening programs in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;163:1150–1151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos LL, Traverse D, Turner D, Minish E. Delivering prevention: the role of public programs in delivering care to high risk populations. Med Care. 1999;37:JS264–JS278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaudette LA, Altmayer CA, Nobrega KMP, Lee J. Trends in mammography utilization, 1981 to 1994. Health Rep. 1996;8:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Decker KM, Harrison ML, Tate RB. Satisfaction of women attending the Manitoba Breast Screening Program. Prev Med. 1999;29:22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts JD, Poffenroth LA, Roos LL, Bebchuk JD, Carter AO. Monitoring childhood immunizations: a Canadian approach. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1666–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller AB, Anderson G, Brisson J, et al. Report of a national workshop on screening for cancer of the cervix. Can Med Assoc J. 1991;145(suppl 10):1301–1325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roos LL, Nicol JP, Cageorge SM. Using administrative data for longitudinal research: comparisons with primary data collection. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roos NP, Roos LL, Mossey JM, Havens B. Using administrative data to predict important health outcomes: entry to hospital, nursing home, and death. Med Care. 1988;26:221–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhajarine N, Mustard CA, Roos LL, Young TK, Gelskey DE. Comparison of survey data and physician claims data for detecting hypertension. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roos LL, Nicol JP. A research registry: uses, development, and accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxwell CJ, Bancej CM, Snider J. Predictors of mammography use among Canadian women aged 50–69: findings from the 1966/97 National Population Health Survey. Can Med Assoc J. 2001;164:329–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maxwell CJ, Bancej CM, Snider J, Vik SA. Factors important in promoting cervical cancer screening among Canadian women: findings from the 1996–97 National Population Health Survey (NPHS). Can J Public Health. 2001;92:127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J, Parsons GF, Gentlemen JF. Falling short of Pap test guidelines. Health Rep. 1998;10:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Grasse CE, O’Connor AM, Boulet J, Edwards N, Bryant H, Breithaupt K. Changes in Canadian women’s mammography rates since the implementation of mass screening programs. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:927–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roos NP, Mustard CA. Variation in health and health care use by socioeconomic status in Winnipeg, Canada: does the system work well? Yes and no. Milbank Q. 1997;75:89–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Statistics Canada. Postal Code Conversion File: Detailed User Guide. Ottawa, Ontario: Geography Division, Statistics Canada; 1988.

- 30.Mustard CA, Derksen S, Berthelot J-M, Wolfson W. Assessing ecologic proxies for household income: a comparison of household and neighbourhood-level income measures in the study of population health status. Health Place. 1999;5:157–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen MM. Using administrative data for case-control studies: the case of the Papanicolaou smear. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young TK, Kliewer E, Blanchard JF, Mayer T. Monitoring disease burden and preventive behavior with data linkage: cervical cancer among aboriginal people in Manitoba, Canada. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1466–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martens P, Bond R, Jebamani L, et al. The Health and Health Care Use of registered First Nation People Living in Manitoba: A Population-Based Study. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy; April2002.

- 34.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1990.

- 35.Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 4th ed. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth Publishing Co; 1995.

- 36.Mason BW, Donnelly PD. Targeted mailing of information to improve uptake of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine: a randomised controlled trial. Commun Dis Public Health. 2000;3:67–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elliman D, Bedford H. MMR vaccine: the continuing saga. BMJ. 2001;322:183–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jefferson T. Real or perceived adverse effects of vaccines and the media—a tale of our times. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:402–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brownell MD, Martens P, Kozyrskyj A, et al. Assessing the Health of Children in Manitoba: A Population-Based Study. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation; February2001:159.

- 40.Goel V. Factors associated with cervical cancer screening: results from the Ontario Health Survey. Can J Public Health. 1994;85:125–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gyorkos TW, Tannenbaum TN, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of immunization delivery methods. Can J Public Health. 1994;85(1 suppl 1):S14–S30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierce C, Goldstein M, Suozzi K, Gallaher M, Dietz V, Stevenson J. The impact of the standards for pediatric immunization practices on vaccination coverage levels. JAMA. 1996;276:626–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shefer A, Briss P, Rodewald L, et al. Improving immunization coverage rates: an evidence-based review of the literature. Epidemiol Rev. 1999;21:96–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szilagyi PG, Bordley C, Vann JC, et al. Effect of patient reminder/recall interventions on immunization rates. JAMA. 2000;284:1820–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gentleman JF, Lee J. Who doesn’t get a mammogram? Health Rep. 1997;9:19–28.9474504 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colditz GA, Hoaglin DC, Berkey CS. Cancer incidence and mortality: the priority of screening frequency and population coverage. Milbank Q. 1997;75:147–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skinner CS, Stretcher VJ, Hospers H. Physicians’ recommendations for mammography: do tailored messages make a difference? Am J Public Health. 1994;84:43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis TC, Arnold C, Berke HJ, Nandy I, Jackson RH, Glass J. Knowledge and attitude on screening mammography among low-literate, low-income women. Cancer. 2001;78:1912–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hofer TP, Katz SJ. Healthy behaviors among women in the United States and Ontario: the effect on use of preventive care. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1755–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bottorff JL, Johnson JL, Bhagat R, et al. Beliefs related to breast health practices: the perceptions to South Asian women living in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:2075–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitchell SM, Shortell SM. The governance and management of effective community health partnerships: a typology for research, policy, and practice. Milbank Q. 2001;78:241–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hislop TG, Clarke HF, Deschamps M, et al. Cervical cytology screening: how can we improve rates among First Nations women in urban British Columbia? Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:1701–1708. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]