Abstract

Objectives. We analyzed age, time period, and cohort effects on trends in adolescent cigarette smoking in California from 1990 to 1999.

Methods. Data from subjects aged 12 to 17 years (n = 26 536; 50.4% male) from the California Tobacco Survey and the California Youth Tobacco Survey were analyzed, and never smokers were used as the outcome measure.

Results. The proportion of never smokers increased from 60% for males and 66% for females in 1990 to around 70% for both sexes in 1999. Respondents were more likely to be never smokers if born in 1978 or later (i.e., aged 12 years or younger in 1990, when most tobacco control programs started in California).

Conclusions. The statewide antitobacco programs prevented adolescents from starting to smoke, primarily through a cohort effect.

Preventing children and adolescents from becoming cigarette smokers is an important public health objective.1 One of the strongest predictors of tobacco addiction in adulthood is experimentation with smoking during adolescence.2 Therefore, preventing adolescents from starting to smoke is an important strategy for preventing tobacco-related morbidity and mortality later in life. In the past 2 decades, large-scale, comprehensive tobacco control programs have been implemented in several states, including California. Now that an entire generation has passed through childhood and adolescence with tobacco control programs as part of its living environment, it is possible to examine secular trends in smoking initiation.

California is among the few states that have devoted great efforts to control tobacco. The passage in California of Proposition 99—the Tobacco Tax and Health Promotion Act of 1988—led to a proliferation of tobacco control and prevention programs, many of which had reached full implementation by 1990. Preventing adolescents from beginning to smoke has been a priority of these tobacco control efforts.3,4 Studies using smoking prevalence as an outcome measure indicate a decline in current smoking in the past decade for adults, but not for adolescents.3 However, measures of current smoking do not specifically assess the proportion of adolescents who have been prevented from ever trying tobacco. Focusing on adolescents who had never smoked a cigarette, this analysis examined, using the age–period–cohort (APC) method, a 10-year trend of smoking behavior in California since 1990.

Outcomes of a tobacco control effort for an adolescent population can be measured with various indicators, such as prevalence of past-month or daily smoking, number of cigarettes smoked, changes in risk of smoking onset, and average age at smoking onset.3,5,6 Most analyses of adolescent smoking prevalence have used measures of recent smoking, such as past 30-day smoking. However, this measure makes no distinctions between occasional or experimental smokers, addicted smokers, and adolescents who first tried smoking in the past 30 days. It also does not detect those adolescents who have experimented with smoking, but not in the past month.

Among various smoking measures, perhaps the most specific and straightforward is the proportion of adolescents who remain never smokers. A never smoker can be defined as a respondent who has never tried smoking, not even a few puffs of a cigarette. The concept of this measure is clear and simple, and data for the variable are available from tobacco and other behavioral risk factor surveys conducted at both the local and national levels. This measure also is consistent with the stated goal of most tobacco control programs to prevent adolescents from obtaining or starting use of any tobacco.

This study investigated the possible effects of age, time period, and birth cohort on secular trends in adolescent cigarette smoking in California, using the APC method, and it provides further data to demonstrate the effectiveness of health promotion strategies in preventing adolescent smoking.

METHODS

Study Population and Data Sources

This analysis focused on the California adolescent population aged 12 through 17 years. Data used for this analysis were from the 1990–1991, 1992, and 1993 California Tobacco Survey (CTS) (Youth Component) and the 1994–1999 annual California Youth Tobacco Survey (CYTS). These surveys were conducted primarily for assessing smoking prevalence and other issues related to tobacco use and control in California. Both the CTS and the CYTS data were collected among randomly sampled respondents throughout California.

Households were first randomly selected with a modified Waksberg–Mitofsky random-digit-dialing methodology. Adolescents aged 12 through 17 years within these sampled households were then scheduled for extended telephone interviews. The interviews for both the CTS and the CYTS were conducted with a computer-assisted telephone interviewing technique. The 3 phases of the CTS were conducted from June 1990 through February 1991, March through July 1992, and January through May 1993. Each annual CYTS from 1994 to 1999 was conducted throughout the whole year. The response rate among eligible subjects for the CTS was 78% in 1990 and 1991, 78% in 1992, and 81% in 1993.3 The response rate for the CYTS was 71% in 1994, 74% in 1995, 76% in 1996, 67% in 1997, 76% in 1998, and 86% in 1999.7

Definition and Description of Never Smokers

In this analysis, never smokers were defined as respondents who answered no to the question “Have you ever smoked a cigarette?” in the CTS or to the question “Have you ever tried or experimented with cigarette smoking, even a few puffs?” in the CYTS. Annual proportions of never smokers (number of never smokers divided by total respondents) were computed by sex. The computed annual age-specific proportions of never smokers were then used as the input for APC analyses. To satisfy the conditions required by the APC modeling, midyear proportions of never smokers by age for the years 1990–1993 were interpolated with a 3-point linearinterpolation technique.8 This interpolation was based on 4 annual consecutive data sets collected in 1990–1991, 1992, 1993, and 1994.

APC Modeling

The APC modeling analysis is a statistical method for estimating the effects of age, time period, and cohort on an observed secular trend.9,10 This method has been widely used in analyzing secular trends for many vital rates in epidemiological studies.11–17 Few studies can be found in the literature that have ever used APC modeling in describing smoking trends in adolescent populations. We used the following general APC model9,10 for this analysis:

|

1 |

where ψi j k represents the dependent variable; μ represents the overall mean; αi, βj, and Yk represent the effects of age, period, and cohort, respectively; and ei j k represents a normally distributed error term with a mean of zero. Depending on the frequency of the event of interest, ψi j k could be either a log (rare event) or logit (common event) transformation of the observed rates or proportions for cohort k (k = 1, 2, 3, . . . K) at age group i (i = 1, 2, 3, . . . I) during period j (j = 1, 2, 3, . . . J).

The annual age-specific proportions of never smokers were used as dependent variables for statistical analysis. From the general model shown above, 4 APC models were derived and used: the AP (age–period), AC (age–cohort), PC (period–cohort), and full APC models. A logit transformation was conducted over the computed proportions of never smokers. The logit transformation was selected instead of the log because the age-specific proportion of never smokers in this study (range = 35%–95%) indicated that the binomial distribution would be appropriate for modeling the data.18 The 3 independent variables of age (6 groups), period (10 years), and cohort (15 birth years) were coded as 28 ([6 − 1] + [10 − 1] + [15 − 1]) dummy variables for model fitting. The GENMOD procedure in SAS was used for parameter estimation.18

When fitting the 2-term models of AP, AC, and PC, we constrained no parameters because the models were mathematically identifiable. One reference point (effect = 0) was used for each of the 3 independent variables: the age group 14, the period 1994, and the birth cohort 1980. These 3 points were selected empirically as references after a comparison of results from models with different reference points. Using these midpoints or approximate midpoints rather than other points as references led to more robust parameter estimation.

There are several alternative methods to handle the nonidentifiability problem for the full APC model. These include (1) setting constraints to the parameters to be estimated,19,20 (2) separating the estimable (curvature) part of the effects from the linear nonestimable part,10,20,21 and (3) expanding one parameter to be a function of other variables.21,22 We handled this problem by setting the effect of a cohort adjacent to the reference point as zero. To specify the model this way, the number of equations was equal to the number of parameters to be estimated in the full APC model.

The selection of a cohort adjacent to the reference cohort, followed by the arbitrary setting of a zero effect to this point, was based on the data from our preliminary analyses and the following 2 considerations. First, age effect was not appropriate because it changes substantially from one age to another; it was not possible to find 2 adjacent age groups with a similar level of effect. Second, analysis from 2-term APC models demonstrated that there were several adjacent cohorts with similar effect levels; there were also more data points in the cohort than in the period for selection. We therefore chose to find points from cohort effect rather than from period effect as reference and constraint.

The actual steps used to identify the 2 adjacent cohorts for APC modeling in this study were as follows: a 2-term AC modeling analysis was conducted to obtain a set of estimated cohort effects γk (k = 1, 2, 3, . . . 15). Then the minimum among all (γk − γk + 1) for k = 1, 2, 3, . . . 14 resulted in effects for 2 adjacent cohorts γm and γm + 1. One of these 2 points was set as the reference and another automatically became the constraint. Finally, the 1976 birth cohort was set as zero effect and the 1977 birth cohort as the reference for males; the 1981 birth cohort was set as zero and the 1982 birth cohort as the reference for females.

The statistic of deviance/degree of freedom (df) ratio was used as the measure of the goodness of fit, and a value of 1.50 or less for the statistic was adopted as a criterion of a satisfactory goodness of fit.23 In addition, a residual analysis also was conducted to examine the fit between the observed data and the predicted result. An approximately normal distribution of the residuals around zero within a relatively narrower band was set as the indication of a good model fit.23

RESULTS

Data from 26 536 respondents were used to compute the annual age-specific proportions of never smokers for the period 1990–1991 to 1999. Among the respondents, 12 292 (46%) were from the CTS and the rest from the CYTS, 50.4% were male, 50.8% were White, 32.6% were Hispanic/Latino, 6.4% were African American, 7.8% were Asian American, and 2.4% were of other races/ethnicities (Table 1 ▶). The respondents were aged 12 through 17 years (mean = 14.42, SD = 1.68). There were no significant differences in age, sex, or race/ethnicity (P > .05) across data sources. There were 43 subjects in the original data sets with recorded ages of older than 17 years (42 aged 18, 1 aged 19); these subjects were excluded from the analysis.

TABLE 1—

Data Sources and Sample Characteristics: Adolescent Respondents to the California Tobacco Survey and the California Youth Tobacco Survey

| Age (y) at Survey (%) | Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||||||

| Survey and Year | Total No. Subjects | 12–13 | 14–15 | 16–17 | Male (%) | White | Hispanic/Latino | African American | Asian American |

| California Tobacco Survey | |||||||||

| 1990–91 | 5015 | 34.02 | 33.84 | 32.14 | 50.49 | 57.51 | 26.08 | 5.84 | 8.00 |

| 1992 | 1782 | 35.30 | 33.84 | 30.86 | 49.38 | 52.24 | 30.64 | 6.51 | 8.25 |

| 1993 | 5495 | 34.69 | 34.09 | 31.23 | 51.21 | 55.65 | 27.84 | 5.79 | 8.39 |

| Subtotal | 12 292 | 34.50 | 33.95 | 31.55 | 50.65 | 55.91 | 27.53 | 5.91 | 8.21 |

| California Youth Tobacco Survey | |||||||||

| 1994 | 1738 | 36.54 | 34.52 | 28.94 | 49.37 | 48.68 | 32.51 | 7.31 | 8.80 |

| 1995 | 2153 | 35.21 | 34.84 | 29.96 | 50.49 | 46.73 | 34.42 | 6.36 | 9.38 |

| 1996 | 2504 | 34.03 | 34.58 | 31.39 | 50.60 | 46.73 | 36.30 | 6.39 | 8.07 |

| 1997 | 2691 | 34.86 | 33.85 | 31.29 | 50.76 | 48.42 | 36.08 | 6.35 | 7.88 |

| 1998 | 2460 | 34.88 | 33.17 | 31.95 | 51.30 | 44.96 | 39.88 | 7.56 | 5.45 |

| 1999 | 2698 | 34.62 | 34.66 | 30.73 | 48.85 | 43.81 | 40.44 | 7.49 | 6.12 |

| Subtotal | 14 244 | 34.93 | 34.25 | 30.83 | 50.25 | 46.43 | 36.91 | 6.90 | 7.50 |

| Total | 26 536 | 36.87 | 36.34 | 33.26 | 50.44 | 50.82 | 32.57 | 6.44 | 7.83 |

Note. Statistical analysis indicated no significant differences in age, sex, or ethnicity compositions between the California Tobacco Survey and the California Youth Tobacco Survey data. A total of 1179 subjects from the Los Angeles County Minority Health Survey of 1990–1991 were excluded from the analysis owing to increased proportions of ethnic minority respondents in its data, which may affect the estimates of the overall trends.

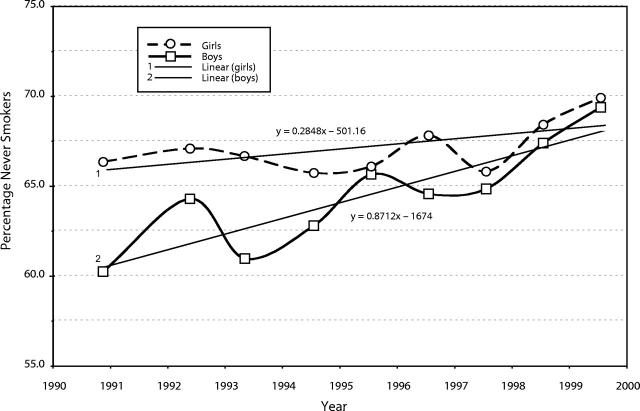

Figure 1 ▶ presents the overall proportion of never smokers by sex from 1990–1991 to 1999. During the period 1990–1991, 60% of adolescent males and 66% of adolescent females were never smokers. The proportions increased to 69% and 70% in 1999 for males and females, respectively. A linear regression analysis of the trend indicated that the proportion of adolescent never smokers increased annually by 0.87% and 0.29% for males and females, respectively.

FIGURE 1—

Secular trends in never smoking among adolescent boys and girls aged 12 through 17 years: California, 1990–1999.

An inspection of the computed proportions of never smokers by year and age (data not shown) indicated a significant age effect. As age increased, the proportion of never smokers declined from approximately 85%–95% to about 35%–50% for both sexes. However, the period and cohort effect could not be seen clearly without APC modeling analyses. In Table 2 ▶, it can be seen that the data fit various APC models well according to the goodness-of-fit criterion, except for the PC model for females. For this model, the deviance/df ratio was 1.82, which was greater than the criterion of 1.50. Residual analysis indicated that the APC model and the AC model for both sexes provided the narrowest residual range (bottom row in Table 2 ▶), indicating a better fit than the others. The PC model resulted in the largest residual range for both males (16.984) and females (19.862), indicating the worst fit. This is reasonable because these 2 models did not include age, a variable with an apparent effect on secular trends.

TABLE 2—

Estimated Age, Period, and Cohort Effects for the Trends of Adolescent Never Smokers in California by Various Age–Period–Cohort Models

| Male | Female | |||||||

| Model | AC | AP | PC | APC | AC | AP | PC | APC |

| Intercept (μ) | 0.641 | 0.804 | 0.353 | 0.739 | 0.632 | 0.720 | 0.465 | 0.625 |

| Age (αi) | ||||||||

| 12 | 1.150 | 1.275 | 1.205 | 1.507 | 1.540 | 1.488 | ||

| 13 | 0.470 | 0.505 | 0.498 | 0.659 | 0.673 | 0.649 | ||

| 14 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| 15 | −0.471 | −0.489 | −0.495 | −0.379 | −0.404 | −0.367 | ||

| 16 | −0.871 | −0.920 | −0.923 | −0.679 | −0.726 | −0.655 | ||

| 17 | −1.024 | −1.129 | −1.108 | −0.779 | −0.842 | −0.743 | ||

| Period (βj) | ||||||||

| 1990 | −0.201 | 1.955 | −0.257 | 0.014 | 1.971 | 0.035 | ||

| 1991 | −0.110 | 1.638 | −0.163 | 0.032 | 1.635 | 0.037 | ||

| 1992 | −0.080 | 1.251 | −0.112 | 0.039 | 1.246 | 0.025 | ||

| 1993 | −0.166 | 0.759 | −0.151 | −0.060 | 0.796 | −0.025 | ||

| 1994 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.350 | −0.060 | ||

| 1995 | −0.157 | 0.323 | −0.130 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| 1996 | 0.028 | −0.450 | −0.006 | 0.068 | −0.383 | 0.013 | ||

| 1997 | −0.022 | −0.998 | −0.101 | −0.001 | −0.907 | −0.106 | ||

| 1998 | 0.139 | −1.345 | 0.011 | 0.123 | −1.274 | −0.053 | ||

| 1999 | 0.223 | −1.806 | 0.025 | 0.186 | −1.720 | −0.053 | ||

| Year of birth (γk) | ||||||||

| 1973 | −0.197 | −2.888 | 0.046 | 0.053 | −2.531 | −0.127 | ||

| 1974 | −0.061 | −2.518 | 0.120 | −0.002 | −2.368 | −0.177 | ||

| 1975 | 0.148 | −1.968 | 0.281 | 0.054 | −2.010 | −0.112 | ||

| 1976 | 0.066 | −1.641 | 0.177 | 0.237 | −1.460 | 0.092 | ||

| 1977 | −0.050 | −1.331 | 0.040 | 0.167 | −1.102 | 0.045 | ||

| 1978 | −0.024 | −0.869 | 0.023 | −0.054 | −0.873 | −0.170 | ||

| 1979 | −0.009 | −0.449 | 0.000 | 0.050 | −0.375 | −0.063 | ||

| 1980 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.089 | ||

| 1981 | 0.118 | 0.550 | 0.095 | 0.081 | 0.499 | 0.000 | ||

| 1982 | 0.239 | 1.103 | 0.191 | 0.076 | 0.915 | 0.000 | ||

| 1983 | 0.357 | 1.599 | 0.283 | 0.219 | 1.408 | 0.154 | ||

| 1984 | 0.256 | 1.953 | 0.165 | 0.216 | 1.830 | 0.165 | ||

| 1985 | 0.337 | 2.514 | 0.225 | 0.312 | 2.415 | 0.272 | ||

| 1986 | 0.442 | 3.093 | 0.287 | 0.404 | 3.100 | 0.362 | ||

| 1987 | 1.094 | 4.338 | 0.917 | 0.394 | 3.787 | 0.358 | ||

| Goodness of fit | ||||||||

| df | 40 | 45 | 36 | 32 | 40 | 45 | 36 | 32 |

| Deviance | 17.529 | 26.204 | 32.949 | 15.317 | 18.025 | 26.032 | 65.461 | 16.870 |

| Deviance/df | 0.438 | 0.582 | 0.915 | 0.479 | 0.451 | 0.578 | 1.818 | 0.527 |

| Range of residuals | 10.516 | 12.662 | 16.984 | 11.500 | 12.848 | 15.109 | 19.862 | 11.487 |

Note. AC = age–cohort model; AP = age–period model; PC = period–cohort model; APC = age–period–cohort model. Logits of the proportion of never smokers by age were used as dependent variables for these modeling analyses.

Results from different APC models in Table 2 ▶ indicated a robust age effect: as age increased, the estimated effect declined. The estimated period effect was similar for the AP and APC models. The period effect estimated with the PC model differed from that estimated with the other 2 models, and the trend of the effect was also opposite to the observed overall trends of never smokers. The estimated cohort effect from the AC and APC models was similar in magnitude and direction for males and females but rather different from the cohort effects estimated with the PC model that did not include age.

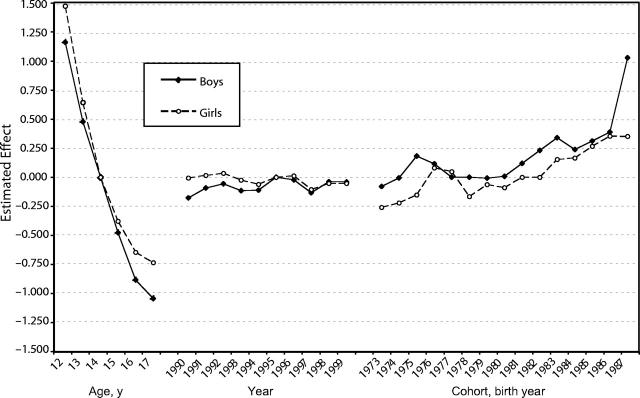

Figure 2 ▶ presents results from the full APC modeling analysis. The age effect on the observed trends of never smokers is clearly depicted: the proportion of never smokers was negatively associated with age at survey. This pattern was similar for both males and females. A slightly increasing trend in the period effect was observed for males but not for females. There was an obvious cohort effect for both sexes. Three distinct segments of the cohort effect can be identified: from 1973 to 1975–1976, from 1975–1976 to 1978–1980, and from 1978–1980 to 1999. There was an increment in the cohort effect for males born from 1973 to 1975 and for females born from 1973 to 1976. This increasing cohort effect declined for both males and females born during the period 1975–1976 before it increased continuously and almost monotonically for females born since 1978 and for males born since 1980.

FIGURE 2—

Estimated age, period, and cohort effects from an age–period–cohort modeling analysis of trends in adolescent never smoking in California, 1990–1999.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The results of this analysis indicate that the proportion of never smokers among California adolescents has increased over time. Although there is a limited period effect on the increasing trends in the number of never smokers, there has been an obvious cohort effect. This effect fluctuated slightly from 1973 to 1978 but has progressively increased since 1978. This evidence demonstrates to what extent adolescents born between 1978 and 1987 have contributed to the increasing trend toward never smoking. Adolescents born in 1978 and later were aged 12 or younger in 1990, when most of the statewide tobacco control programs first launched in California.3,5 This finding suggests that the tobacco control program in California may have protected adolescents from starting to smoke cigarettes if they were exposed to the program at 12 years of age or younger, or, alternatively, that the California tobacco control programs and efforts targeting adolescents were more effective for those who were aged 12 years or younger than for those who were older. According to this finding, a continuous tobacco control effort with a focus on preventing adolescents from starting cigarette smoking would be of great strategic importance.

There is a strong age effect on the trends of never smokers (both males and females) as age increases, the proportion of never smokers declines progressively. This result is consistent with reports that risk for smoking initiation increases with age.24–26 This finding underscores the importance of preventing early onset of cigarette smoking among adolescents. It is worth noting that the age effect estimated from the APC modeling analysis differs from the effect of age composition in the computed proportion (or rate) in many demographic, vital statistic, and epidemiological analyses in which number of subjects by age is used as a weight.

Previous studies suggested that adolescent smoking in California remained essentially constant during the 1990s.4 The present analysis, in contrast, suggests that California tobacco control efforts may have successfully protected a substantial number of adolescents from starting to smoke cigarettes during the period 1990–1999. This apparent contradiction is worth exploring further. The cohort effect revealed in this study indicates that it is the newly entered birth cohorts born after 1978 that could be protected from smoking onset. The impact of the newly included never smokers on the overall smoking prevalence measures would therefore become obvious only when the adolescents from the birth cohorts of 1978 and later became the majority of the study population aged 12 through 17 years. Consequently, we would expect an obvious decline in smoking prevalence to appear in the mid- or later 1990s, when most subjects in the study population were from these more recent cohorts. Also, findings from this study suggest that the APC method can be used to describe health behavior15,27–29 as well as to assess the effectiveness of tobacco control efforts.

There are some limitations to this analysis. First, not all of the data sets used for the analysis were collected in the middle of the corresponding years. The computed proportions of never smokers with these data sets had to be interpolated to represent the midyear levels of never smokers. Errors might have been introduced if there were significant seasonal changes in the risk of smoking initiation among these adolescents. There are no data available on seasonal changes in risk of smoking onset; therefore, no adjustment can be made when the proportions are interpolated. These interpolated results for the period 1990–1994 should be used with caution.

Second, data used for this analysis were from telephone surveys. Although documented studies have shown that computer-aided telephone survey data are generally reliable,30,31 there could have been an overreporting of never smoking because the adolescent respondents were at home when the telephone interviews were conducted. Even though such overreporting might have little effect on the secular trends if it occurred randomly, caution should be used when referring to levels of the proportion over time.

Third, the nonidentifiability of the full APC model casts a shadow on the results derived from it. Although new methods for handling the nonidentifiability problem have been developed and tested in other reported studies,10,19,20,32,33 the problem theoretically remains. We used an objective procedure in this analysis; results from the analysis are consistent with that from the related 2-term models, suggesting an empirical approach to the problem. However, this does not mean that the nonidentifiability problem really has been solved.

Given these limitations, this analysis is the first to use the APC modeling method to examine the trends of adolescent cigarette smoking in California during the 10-year period beginning in 1990. Information obtained from this study is useful for a better understanding of the observed trends of adolescent cigarette smoking in California; it also sheds light on how to assess the effectiveness of the tobacco control programs in general.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funds from the University of California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Project (award 8RT-0034).

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Southern California.

Contributors X. Chen, the primary contributor, conceptualized the study, directed the statistical analysis, provided most explanations of the findings, and led the development of the article. G. Li improved the solutions to various APC models. J. B. Unger and C. A. Johnson developed and consolidated the study theme, explained the study findings, and helped with development of the article. X. Liu did most of the statistical computations.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Determining the probability of future smoking among adolescents. Addiction. 2001;96:313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierce JP, Gilpin EA, Emery SL, et al. Tobacco Control in California: Who’s Winning the War? An Evaluation of the Tobacco Control Program, 1989–1996. La Jolla: University of California, San Diego; 1998.

- 4.Pierce JP, Gilpin EA, Emery SL, et al. Has the California tobacco control program reduced smoking? JAMA. 1998;280:893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Independent Evaluation Consortium. Final Report of the Independent Evaluation of the California Tobacco Control Prevention and Education Program: Wave 1 Data, 1996–1997. Rockville, Md: The Gallup Organization; 1998.

- 6.Tobacco or Health: A Global Status Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997.

- 7.California Youth Tobacco Survey: SAS Dataset Documentation and Technical Report. Sacramento: California Dept of Health Services, Cancer Surveillance Section; 2000.

- 8.Guolong Z. Linear and exponential interpolation. Cancer Treat Rep. 1986;70:1140–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selvin S. Cohort data: description and illustration. In: Selvin S, ed. Statistical Analysis of Epidemiological Data. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1996:103–125.

- 10.Holford TR. Understanding the effects of age, period, and cohort on incidence and mortality rates. Annu Rev Public Health. 1991;12:425–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rostgaard K, Vaeth M, Holst H, Madsen M, Lynge E. Age–period–cohort modeling of breast cancer incidence in the Nordic countries. Stat Med. 2001;20:47–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu TS, Tse LA, Wong TW, Wong SI. Recent trends of stroke mortality in Hong Kong: age, period, cohort analyses and the implications. Neuroepidemiology. 2000;19:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarone RE, Chu KC. Age–period–cohort analyses of breast-, ovarian-, endometrial- and cervical-cancer mortality rates for white women in the USA. J Epidemiol Biostat. 2000;5:221–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahpar C, Li G. Homicide mortality in the United States, 1935–1994: age, period, and cohort effects. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:1213–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bijnen FC, Feskens EJ, Caspersen CJ, Mosterd WL, Kromhout D. Age, period, and cohort effects on physical activity among elderly men during 10 years of follow-up: the Zutphen Elderly Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M235–M241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson C, Boyle P. Age–period–cohort analysis of chronic disease rates, I: modeling approach. Stat Med. 1998;17:1305–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riggs JE, McGraw RL, Keefover RW. Suicide in the United States, 1951–1988: constant age–period–cohort rates in 40- to 44-year-old men. Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37:222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, Version 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1999.

- 19.Holford TR. The estimation of age, period and cohort effects for vital rates. Biometrics. 1983;39:311–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNally RJ, Alexander FE, Staines A, Cartwright RA. A comparison of three methods of analysis for age–period–cohort models with application to incidence data on non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:32–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robertson C, Gandini S, Boyle P. Age–period–cohort models: a comparative study of available methodologies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:569–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee WC, Lin RS. Autoregressive age–period–cohort models. Stat Med. 1996;15:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models. London, England: Chapman & Hall; 1989.

- 24.Khuder SA, Dayal HH, Mutgi AB. Age at smoking onset and its effect on smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1999;24:673–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen X, Unger JB. Hazards of smoking initiation among Asian American and non-Asian adolescents in California: a survival model analysis. Prev Med. 1999;28:589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douglas S, Hariharan G. The hazard of starting smoking: estimates from a split population duration model. J Health Econ. 1994;13:213–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson RA, Gerstein DR. Age, period, and cohort effects in marijuana and alcohol incidence: United States females and males, 1961–1990. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35:925–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levenson MR, Aldwin CM, Spiro A 3rd. Age, cohort and period effects on alcohol consumption and problem drinking: findings from the Normative Aging Study. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59:712–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Houweling H, Wiessing LG, Hamers FF, Termorshuizen F, Gill ON, Sprenger MJ. An age–period–cohort analysis of 50 875 AIDS cases among injecting drug users in Europe. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:1141–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillmore MR, Catalano RF, Morrison DM, Wells EA, Iritani B, Hawkins JD. Racial differences in acceptability and availability of drugs and early initiation of substance use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16:185–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Severson HH, Glasgow RE, Wirt R, Brozovsky P. Preventing the use of smokeless tobacco and cigarettes by teens: results of a classroom intervention. Health Educ Res. 1991;6:109–120. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson C, Boyle P. Age–period–cohort models of chronic disease rates, II: graphical approaches. Stat Med. 1998;17:1325–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George LK, Siegler IC, Okun MA. Separating age, cohort, and time of measurement: analysis of variance or multiple regression. Exp Aging Res. 1981;7:297–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]