Abstract

Objectives. The authors evaluated the impact of state adult protective service legislation on rates of investigated and substantiated domestic elder abuse.

Methods. Data were collected on all domestic elder abuse reports, investigations, and substantiations for each US state and the District of Columbia for 1999. State statutes and regulations pertaining to adult protective services were reviewed.

Results. There were 190 005 domestic elder abuse reports from 17 states, a rate of 8.6 per 1000 elders; 242 430 domestic elder abuse investigations from 47 states, a rate of 5.9; and 102 879 substantiations from 35 states, a rate of 2.7. Significantly higher investigation rates were found for states requiring mandatory reporting and tracking of numbers of reports.

Conclusions. Domestic elder abuse documentation among states shows substantial differences related to specific aspects of state laws. (Am J Public Health. 2003;93:2131–2136)

The best national estimate is that approximately 550 000 persons aged 60 years or older experienced abuse or neglect, or both, in domestic settings in 1996.1 After adjusting for other factors that might affect mortality, Lachs and Pillemer2 found increased mortality rates among physically abused or neglected elders. Although abuse affects many elders and is associated with increased mortality, there are no clear case-finding guidelines, diagnostic tests, or ideal legal or medical system interventions in the area of elder abuse.3,4 Because of poor public awareness and lack of clear public health or practice guidelines, among other factors, only 21% of the estimated 550 000 cases of abuse occurring in 1996 were reported to and substantiated by adult protective services (APS).1

Since the recognition of elder abuse as a significant social and public health problem,5–7 there have been an array of legislative responses. By 1985, every state had instituted some type of adult protection program, and as of 1993 all states had enacted laws addressing elder abuse in domestic and institutional settings.8 State laws related to elder abuse are extremely diverse,9 containing multiple sections regarding, for example, who is protected, who must report, definitions of reportable behavior, requirements for investigation of reports, penalties, and guardianship.9,10

The effectiveness of abuse reporting and investigation depends, in large part, on the ability of reporters and investigators to recognize mistreatment. However, the ambiguity of relevant protective statutes raises doubt that health care providers, other reporters, and state investigators can identify abuse or neglect.8,9 To date there has been no systematic inquiry regarding elder abuse legislation to determine whether variations in state statutes and regulations relate to differences in reporting and investigation activities. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of state APS legislation on rates of reported, investigated, and substantiated domestic elder abuse.

METHODS

Two sources of data were used in this analysis: (1) the number of domestic elder abuse reports, investigations, and substantiations for each state and the District of Columbia for 1999 or fiscal year 1999–2000 and (2) state statutes and regulations pertaining to APS. The dependent and independent variables, sources and criteria of elder abuse data, and statute and regulation coding are described in the sections to follow.

Dependent and Independent Variables

Four dependent variables were included in the initial analysis: (1) elder abuse report rates, (2) investigation rates, (3) substantiation rates, and (4) the substantiation ratio, determined by dividing substantiated rates by investigation rates. Rates were determined by dividing the number of reports, investigations, and substantiated elder abuse investigations by the total elderly population. Eligibility ages were determined by state law. In states with statutes covering adults 18 years and older, abuse data were obtained for the population 60 years and older. Therefore, the total elder population comprised individuals 60 years and older in all states except California, Maryland, and Nebraska, where state law stipulates the elderly population as those 65 years and older, and Alabama, where this population is defined as those 55 years and older. We defined “report” as an allegation of abuse received by APS, “investigation” as the process undertaken to evaluate the potential victim after a report has been filed, and “substantiation” as the finding that abuse actually exists according to state law.

There were 19 independent variables: 12 related to concepts found in the APS statutes, 2 related to administrative responses from each state’s APS administrator, and 5 related to demographics (Table 1 ▶). Legal variables were derived from the statutes and included several measures of the depth of legislative interest in the issues surrounding elder abuse: mandatory reporting, description of mandatory reporters, definition of self-neglect, definition of eligibility criteria (dependent/vulnerable) in terms of categories of individuals covered by the APS statute, existence of a regulation, penalties for failure to report alleged abuse, education for APS caseworkers, education about elder mistreatment for the general public, total number of words in all abuse definitions, number of abuse definitions in the statutes, and number of abuse definitions in the regulations. Proportions of regulations that mimicked statutes’ abuse definitions were generated from findings in the statutes and regulations.

TABLE 1—

Means, Standard Deviations, and Sample Sizes of Outcomes (Investigation Rates, Substantiation Rates, and Substantiation Ratios), by Level of Qualitative Predictor

| Investigation Rate (× 10−3) | Substantiation Rate (× 10−3) | Substantiation Ratio, % | ||||

| Mean (SD) | No. of States | Mean (SD) | No. of States | Mean (SD) | No. of States | |

| Overall | 5.5 (2.9) | 47 | 2.7 (2.2) | 35 | 44.8 (19.3) | 35 |

| Mandatory reporting required | ||||||

| Yes | 5.8 (2.9) | 42** | 2.8 (2.2) | 32 | 44.4 (19.9) | 32 |

| No | 3.0 (0.7) | 5** | 1.5 (0.5) | 3 | 48.5 (17.7) | 3 |

| Mandatory reporter term listed | ||||||

| Specific person such as nurse, social worker | 6.0 (3.0) | 27 | 3.0 (3.0) | 17 | 43.0 (21.6) | 17 |

| “Any person” | 4.6 (3.4) | 6 | 1.8 (1.5) | 6 | 34.9 (19.2) | 6 |

| Specific person plus “any person” | 6.0 (2.4) | 9 | 3.3 (1.7) | 9 | 53.4 (12.7) | 9 |

| State tracks “reports” | ||||||

| Yes | 7.3 (3.1) | 16*** | 4.7 (2.3) | 12† | 57.3 (15.1) | 12*** |

| No | 4.5 (2.3) | 31*** | 1.7 (1.1) | 23† | 38.2 (18.1) | 23*** |

| Self-neglect defined in statute | ||||||

| Yes | 5.2 (2.9) | 29 | 2.6 (2.3) | 20 | 44.2 (18.9) | 20 |

| No | 6.0 (3.0) | 18 | 2.8 (2.1) | 15 | 45.4 (20.4) | 15 |

| Dependent or vulnerable person covered by statute | ||||||

| Yes | 5.6 (3.3) | 19 | 3.0 (2.6) | 14 | 46.9 (20.3) | 14 |

| No | 5.4 (2.7) | 28 | 2.6 (1.8) | 21 | 43.3 (18.9) | 21 |

| Regulation exists | ||||||

| Yes | 5.3 (2.9) | 40 | 2.7 (2.3) | 29 | 44.8 (19.7) | 29 |

| No | 6.3 (2.8) | 7 | 2.7 (1.5) | 6 | 44.5 (18.6) | 6 |

| Penalty failure report in statute | ||||||

| Yes | 6.1 (3.1) | 31* | 3.0 (2.3) | 23 | 45.0 (19.3) | 23 |

| No | 4.3 (2.1) | 16* | 2.2 (1.8) | 12 | 44.3 (20.0) | 12 |

| Investigates both child and adult allegations | ||||||

| Yes | 4.7 (3.4) | 11 | 1.6 (1.2) | 9* | 33.4 (14.6) | 9** |

| No | 5.7 (2.7) | 36 | 3.1 (2.3) | 26* | 48.7 (19.3) | 26** |

| Education for APS caseworkers | ||||||

| Yes | 5.5 (3.5) | 10 | 2.8 (2.5) | 10 | 45.1 (18.6) | 10 |

| No | 5.5 (2.8) | 37 | 2.7 (2.1) | 25 | 44.6 (19.9) | 25 |

| Elder abuse education for the public | ||||||

| Yes | 5.5 (3.8) | 11 | 2.7 (2.5) | 11 | 43.0 (21.4) | 11 |

| No | 5.5 (2.6) | 36 | 2.7 (2.0) | 24 | 45.6 (18.6) | 24 |

| Investigation Rate (× 10−3) | Substantiation Rate (× 10−3) | Substantiation Ratio, % | |

| Note. APS = adult protective services. | |||

| *P < .10; **P < .05; ***P < .01; †P < .001. | |||

| Spearman estimates of correlations (rs) between outcomes and quantitative predictors | |||

| No. of words in all abuse definitions | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.18 |

| No. of statute abuse definitions | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| No. of regulation abuse definitions | 0.11 | 0.34† | 0.44* |

| Proportion of regulations that mimic statute definition | −0.05 | −0.14 | −0.30 |

| Proportion of total population categorized as elderly | −0.23 | −0.35* | −0.30† |

| Total expenditures per capita | 0.09 (n = 28) | 0.33 (n = 19) | 0.32 (n = 19) |

| Population density | −0.16 (n = 47) | −0.04 (n = 35) | 0.24 (n = 35) |

| Per capita income | −0.07 (n = 40) | 0.05 (n = 29) | 0.35 (n = 29) |

| Child poverty | 0.008 (n = 40) | 0.20 (n = 29) | 0.15 (n = 29) |

The mandatory reporting variable was dichotomous, with “yes” indicating present in statute and “no” indicating not present. The description of mandatory reporters was categorical, with 4 levels: not included in statute, list of identifiable reporters, statement indicating “any person,” and a combination of list of identifiable reporters and statement indicating “any person.” All other legal variables were dichotomous yes/no variables except for the word counts, numbers of definitions, and proportions of regulations mimicking statute definitions.

All statutes were transferred to Microsoft Word files directly from the Internet or scanned from paper copies. These files were prepared for entry into the qualitative software package Atlas.ti.10 All abuse definitions were coded in Atlas.ti and exported to a Word file in which the word counts were completed.

Eight types of abuse definitions were coded in the statutes: (1) abuse not otherwise specified, (2) abandonment, (3) emotional abuse, (4) exploitation, (5) neglect, (6) physical abuse, (7) self-neglect, and (8) sexual abuse. Self-neglect was examined as a separate measure, and all definitions of self-neglect were included in the analysis.

As mentioned, the final legal variable was the proportion of regulations that mimicked the statute definition. Each abuse definition in the regulation was compared with the statute definition and coded in one of 3 ways: (1) identical to or mimicked the statute definition, (2) included less detail than the statute definition, or (3) expanded on the statute definition. The regulation definition count was tallied, and the proportion of regulations that mimicked the statute definition was determined by dividing the number of regulation definitions mimicking statute definitions by the total number of definitions that mimicked, included less detail, or expanded on statute definitions.

The 2 variables obtained from APS agency administrators were (1) whether states tracked elder abuse reports and (2) whether child and adult allegations of abuse were investigated by the same caseworkers. If a state provided information on numbers of reports of allegations and also provided information on numbers of investigations, that state was considered to track reports and to differentiate reports from investigations. Seventeen states provided report numbers (dependent variable) that were higher than their investigation numbers, and these states were categorized as “yes” for having reports distinguished from investigations. Responses from administrators were coded as dichotomous for investigations of both child and adult allegations of abuse.

The 5 demographic variables were as follows: proportion of total population categorized as elderly, total expenditure per capita by departments governing APS, population density, per capita income, and child poverty. Proportion of total elder population was determined by dividing the population 60 years and older by the total population (except in the cases of California, Maryland, and Nebraska, in which the population 65 years and older was divided by the total population, and Alabama, in which the population 55 years and older was divided by the total population).

Data on population density, per capita income, and child poverty were obtained from the April 2000 US census.11 Expenditure data for state agencies providing APS were obtained for 31 states that responded to the 2000 survey administered by the National Association of Adult Protective Services Administrators (NAAPSA) (written communication, J. Otto, NAAPSA executive director, February 2002).

Elder Abuse Data

In November 2000, each state APS administrator received a letter requesting data. Data requested included number of domestic elder abuse reports, investigations, and substantiations of investigations in each state for 1999 or fiscal year 1999–2000. The request specified that administrators omit numbers involving institutionalized persons and persons aged 18 to 59 years. All state APS administrators were contacted within 2 weeks of the initial letter to clarify and discuss the nuances of the data needed for this study. Excluded from the analyses of investigation rates were data from Georgia and North Dakota (state administrators indicated that they had no data to provide), Colorado (provided data but indicated uncertainty as to their accuracy), and Ohio (provided report data but not investigation data).

The data covered all types of elder abuse, including self-neglect, and encompassed information in various formats, such as frequency counts of all reports of abuse and summations of each type of abuse. The terminology used to describe elder abuse varied. Some states provided a number for all categories of abuse, whereas other states used categories of abuse, neglect, and exploitation. Additional states used numerous terms, such as physical abuse, emotional abuse, exploitation, material abuse, neglect, self-neglect, and sexual abuse. Rhode Island was unable to provide self-neglect data, but otherwise all states provided comprehensive numbers relating to abuse.

Different methods of data collection were used for different states, depending on whether the state had data on reports, investigations, substantiations, allegations (possibly more than 1 type of abuse allegation per report), substantiations of allegations, or substantiations of investigations. If categories or terms not used by other states were used in a state report, clarification was sought from the state administrator so that comparisons of state data could be completed. For example, substantiations were designated by many different terms across state reports. In this study, substantiation included the following designations: confirmed, founded, reason to believe, substantiated, and valid.

The data collection process required 13 months to complete, with an average of 25 telephone calls per state (range: 1 to 32). Here we provide the data analysis for domestic elder abuse reports (17 states), investigations (47 states), and substantiations of investigations (35 states). Only 12 states provided data in all 3 areas (reports, investigations, and substantiations). Alaska and Rhode Island’s percentages of substantiated abuse were estimated by their APS administrators as 80% and 70%, respectively. We conducted data analyses that included and excluded these 2 states and found similar results. The data presented here include the estimates for these states.

APS Statutes/Regulations

The state laws analyzed for this study addressed elder abuse in domestic settings and typically were implemented by state APS programs/agencies or state aging agencies. Many states have additional legislation pertaining to elders, including the laws required by the federal Older Americans Act and long-term care ombudsman program, licensing laws for various elder care institutions and facilities, laws pertaining to functioning of the Medicaid Fraud Control Unit, and laws relating to criminal prosecution of certain types of elder abuse or neglect. These additional laws were not included in the analysis.

APS statutes for all states and the District of Columbia were obtained through the Westlaw legal database (http://web2.westlaw.com). The initial search included the specific statutory citation for each state’s statute, obtained from the National Center on Elder Abuse Web site (http://www.elderabusecenter.org). A Boolean search for the keywords “adult protective services,” “elder abuse,” “protective services for adults,” “endangered adults,” or “older persons” followed to confirm the APS statute and to locate other statutes that might be linked to it. The most current versions of the statutes (with a cutoff date of December 31, 2000) were obtained.

Because there is much variability in the APS statutes, comparisons are difficult. We established a coding process to help identify comparable sections in the states’ statutes. As the statutes were being compiled, the research team began developing a code list. Each team member developed an initial code list, and consensus was reached on a uniform set through a series of team meetings. A list of 83 codes was developed that covered all sections of the statutes. Codes used for this report included the following: abandonment, abuse not otherwise specified, age, dependent adult, eligibility criteria, emotional abuse, exploitation, reporting mandatory, neglect, physical abuse, reporting requirements, tracking of reports, penalties for failure to report, caseworker investigation of both child and elder abuse cases, sexual abuse, self-neglect, and vulnerable adult.

State statutes were coded by 6 team members: a physician, a nurse, a lawyer, a social worker, a social work graduate student, and a law graduate student. The following guidelines were used in randomizing states to reviewers: each reviewer was assigned 17 states, 2 experts in the same discipline were not paired, and the 2 graduate students were not paired. After each team member had coded the statute, the team members assigned to the same state compared codes. If consensus on coding was not reached, the text under review was brought to the entire team. Forty-one areas of concern were brought forward to the entire team from 19 different states. Consensus was reached after a review by the team. Using the current list of 83 codes, we applied 2024 codes to the text of all statutes after the initial coding and entered them into Atlas.ti for further qualitative analysis.

Statistical Analysis

In the case of qualitative predictors, we analyzed the outcomes (report, investigation, and substantiation rates and substantiation ratio) using 2-sample t tests or 1-way analysis of variance models, depending on the number of categories within each predictor. Spearman’s rank-based method was used as a robust estimator of correlation between quantitative predictors and outcomes. Chi-square skewness/kurtosis tests of normality revealed that substantiation rate was skewed in the positive direction; thus, analysis of this outcome was repeated after application of a square root transformation. Because the results for the original and transformed scales were very similar, only the findings involving the original scale are presented.

RESULTS

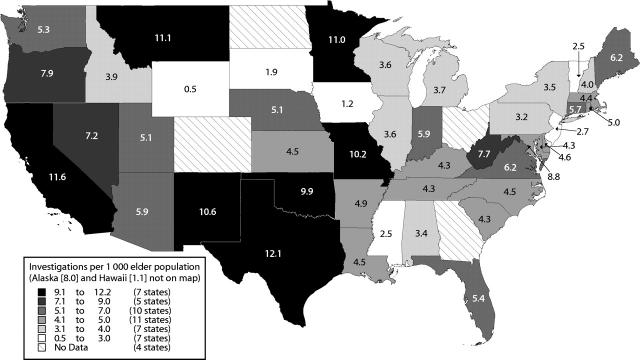

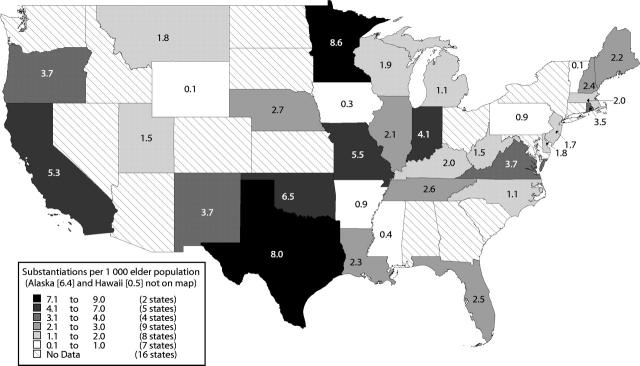

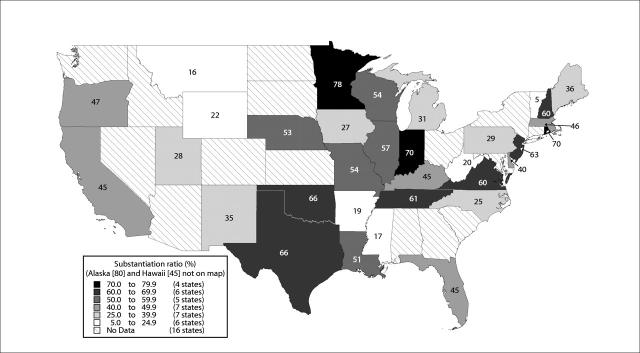

In 1999, there were 190 005 domestic elder abuse reports from 17 states, a rate of 8.6 per 1000 elders; 242 430 investigations from 47 states, a rate of 5.5 per 1000 (Table 1 ▶); and 102 879 substantiations from 35 states, a rate of 2.7 per 1000 (Table 1 ▶). Report rates ranged from 4.5 (New Hampshire) to 14.6 (California) per 1000 elders (Figure 1 ▶), investigation rates ranged from 0.5 (Wyoming) to 12.1 (Texas) (Figure 1 ▶), and substantiation rates ranged from 0.1 (Wyoming and Vermont) to 8.6 (Minnesota) (Figure 2 ▶); the mean substantiation ratio was 44.8% (Figure 3 ▶).

FIGURE 1—

Domestic elder abuse investigation rates.

FIGURE 2—

Domestic elder abuse substantiation rates.

FIGURE 3—

Domestic elder abuse substantiation ratio.

Analyses were performed for report, investigation, and substantiation rates, as well as the substantiation ratio. The sample size for report rates was much smaller (n = 17) than for the other 3 variables, and the details of this analysis were not included in Table 1 ▶. The only significant finding was the correlation between higher report rates and states requiring public education regarding elder abuse (df = 15; t = 2.75, P = .015).

Higher investigation rates were associated with a mandatory reporting requirement and the presence of a statute clause regarding penalties for failure to report elder abuse. Lower substantiation rates were associated with a larger proportion of the population categorized as elderly. Substantiation ratios were higher in states having more abuse definitions in their regulations and in states having separate caseworkers for child and elder abuse investigations. States that track or record reports of abuse before initiation of investigations had higher rates of investigations and substantiations and higher substantiation ratios (Table 1 ▶). The relationships with tracking reports remained significant at the .05 level after control for total expenditures on APS agency services per capita.

DISCUSSION

No reported studies in the literature have compiled data from all states on rates of domestic elder abuse reports, investigations, and substantiations and compared those rates with components of state protective service statutes. The complexity of states’ annual reports and the lack of standardized reporting language hindered us in conducting this study. Many states do not keep separate statistics on elders in general or on elders living in community settings. As described earlier, elder abuse report rates among the states ranged from 4.5 to 14.6 per 1000 elders, investigation rates ranged from 0.5 to 12.1, and substantiation rates ranged from 0.1 to 8.6. There were substantial variations in these rates across states. Individual state rates may not be sensitive enough to differentiate factors associated with differences, and a district- or county-level rate may prove to be more indicative.

Pillemer and Finkelhor conducted a large-scale study designed to accurately estimate maltreatment of the elderly and reported a domestic elder abuse (excluding self-neglect and financial exploitation) prevalence rate of 32 per 1000.12 Numbers of domestic elder abuse reports in the United States for the period 1993 through 1996 ranged from 184 166 to 224 550, and substantiation rates ranged from 60% to 64%.13,14 In our study, we found 102 879 substantiated cases for 35 states, versus the total national estimates of 551 011 cases of abuse and self-neglect and 115 110 cases (21%) substantiated by APS in 1996.1 The estimate that 21% of actual abuse cases are reported to and substantiated by APS suggests that in 1999 there were 489 900 cases of actual abuse, neglect, or self-neglect in those 35 states for which substantiation data were available. Mistreatment has an effect on many elders, and the handling of its investigation at the state level varies widely, from receipt of a report of abuse to the conclusion of an investigation.

The number of reports and therefore the potential number of cases available for investigation depends on public factors such as community awareness of the issue of elder abuse, content of state APS statutes, and professionals’ knowledge of the state statutes. Higher report rates of abuse correlated with states requiring public education regarding elder abuse, suggesting that increased public awareness increases reporting of elder abuse. The majority of states (44) that required mandatory reporters had high investigation rates. The way in which the mandatory reporting requirement was written into the statute (i.e., listing all mandatory reporters or simply indicating “any person”) was not important. Thirty-three states had a provision for penalties for failure to report abuse, and this factor also was significantly associated with higher investigation rates. Thus, APS statutes do seem to affect APS fieldwork.

Another legal component of 20 state statutes is inclusion of the criterion of adult dependence or vulnerability. It has been suggested that fulfillment of this criterion results in the exclusion of many abused elders who are not considered dependent, thus leading to lower numbers of investigations and substantiations.15 This situation was not found in our study. Investigation rates were almost identical between states with and without a dependence requirement.

We also found that the higher the number of abuse definitions in the regulations, the higher the substantiation rates and ratios. Definitions in regulations may actually help APS workers to better identify the different types of abuse. In comparison with statutes, agency-made rules may be clearer or presented in language that is easier for other people in the profession to understand. Nineteen percent of regulation definitions expanded on the statute definitions. The fact that additional definitions of abuse are spelled out in regulations may also give caseworkers confidence that the agency cares about elder abuse issues.

Statutes and regulations address caseworkers’ investigative duties. State APS administrators reported the investigative roles of caseworkers as either elder abuse investigations only or both elder and child abuse investigations. Caseworkers who investigated only elder abuse reports had a higher substantiation ratio than caseworkers assigned to both child and elder abuse work (48% vs 33%). Assignment of only cases of elder abuse may increase the number of such incidents investigated by caseworkers and therefore increase their expertise.15

A state’s administrative decision to track reports of abuse leads to significantly higher investigation and substantiation rates as well as higher substantiation ratios. It is impressive that tracking of reports nearly tripled the substantiation rate. These results held even when per capita expenditures for APS services were controlled. Requiring that reports be tracked forces APS workers and their supervisors to be accountable and permits monitoring of each worker’s level of effort (and, one hopes, success) with elder abuse victims.

Factors other than statute and regulation concepts were also analyzed. Population density and poverty have been identified as risk factors for reported elder abuse.15 Therefore, state population density, per capita income, and child poverty were analyzed, but they were shown to have no correlation with our outcome variables. Lower substantiation rates were shown to be associated with a higher proportion of the total population categorized as elderly. Dealing with a higher at-risk population may strain the system of investigations, leading to lower substantiation rates.

A limitation of our study is that information on elder abuse reports, investigations, and substantiations was provided as secondary data from 47 different sources. There was a lack of uniformity among state annual reports. Some states documented allegations of different types of abuse against elders but not a composite number of alleged victims investigated and substantiated as being abused. Therefore, those states could not be compared to others for investigation and substantiation rates. Authors of many annual state APS summaries use the category of “reports” when they are actually referring to investigations. In this study, each individual state term had to be defined if we were to know what the data represented. Our interdisciplinary research team assessed each state’s statutes and regulations in detail to codify and standardize definitions across states. This approach minimized some of the variability between states.

A second factor complicating data collection occurred when state administrators were unable to provide data for the elderly in domestic settings. Estimations were calculated with the information on age and living settings in states’ annual data summaries. When estimations were calculated, they were calculated in the same way across states. These difficulties highlight the need for standardization of state systems addressing elder abuse and establishment of a primary data source by a national prevalence study.

This study had several strengths that should be noted. First, an interdisciplinary research team gathered both qualitative and quantitative data. Second, all APS statutes were coded. Finally, all state data were merged together while maintaining the integrity of the data.

CONCLUSIONS

Elder abuse is a serious public health, social, and public safety issue. This is the first national study, to our knowledge, to compare elder abuse investigation and substantiation rates with elements of state laws. We are unaware of any evidence to support the notion that actual elder abuse in any given state would be different from such abuse in any other state. However, states’ documentation of domestic elder abuse shows substantial differences in investigation and substantiation rates among states. Part of this difference can be explained by variations in states’ protective service laws. Statutory requirements for mandatory reporting correlated with increased numbers of reports and investigations of elder mistreatment. To successfully address the growing public health concern of elder abuse, there is a need for improvements in state data collection, increased standardization of legislative responses, and increases in the amount of funding available to research the causes and cures of this potentially lethal problem.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this article was supported by an unrestricted grant (RO6/CCR18677) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Human Participant Protection This research was approved by the University of Iowa institutional review board. Because aggregate state data was used, there were not individualized participant identifiers therefore no informed consent was needed.

Contributors G. J. Jogerst conceived of the study, supervised all aspects of its implementation and contributed to writing the manuscript. J. M. Daly assisted with study development, retrieved study data, completed analyses and contributed to writing the manuscript. J. D. Dawson assisted with the study and completed the analyses. G. A. Schmuch and J. G. Ingram contributed social work input and M. F. Brinig contributed legal aspects. All authors helped to conceptualize ideas, code statutes and regulations, interpret findings, and review drafts of the manuscript.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.National Center on Elder Abuse. The National Elder Abuse Incidence Study. Washington, DC: American Public Human Services Association; 1998.

- 2.Lachs MS, Pillemer K. Abuse and neglect of elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fulmer TT, O’Malley TA. The difficulty of defining abuse and neglect. In: Fulmer TT, O’Malley TA, eds. Inadequate Care of the Elderly. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 1987:13–24.

- 4.Loue SL. Elder abuse and neglect in medicine and law: the need for reform. J Legal Med. 2001;22:159–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf RS. The nature and scope of elder abuse. Generations. 2000;24:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinschmidt KC. Elder abuse: a review. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA, Charlson ME. The mortality of elder abuse. JAMA. 1998;280:428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tatara T. An Analysis of State Laws Addressing Elder Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation. Washington, DC: National Center for Elder Abuse; 1995.

- 9.Moskowitz S. Saving granny from the wolf: elder abuse and neglect—the legal framework. Conn Law Rev. 1998;31:77. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atlas.ti: The Knowledge Workbook. Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development; 1997.

- 11.Profiles of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 2001.

- 12.Pillemer K, Finkelhor D. The prevalence of elder abuse: a random sample survey. Gerontologist. 1988;28:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatara T, Blumerman LM. Summaries of the Statistical Data on Elder Abuse in Domestic Settings: An Exploratory Study of State Statistics for FY 93 and FY 94. Washington, DC: National Center on Elder Abuse; 1996.

- 14.Tatara T, Kuzmeskus LB. Summaries of the Statistical Data on Elder Abuse in Domestic Settings for FY 95 and FY 96. Washington, DC: National Center on Elder Abuse; 1997.

- 15.Jogerst GJ, Dawson JD, Hartz AJ, Ely JW, Schweitzer LA. Community characteristics associated with elder abuse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:513–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]