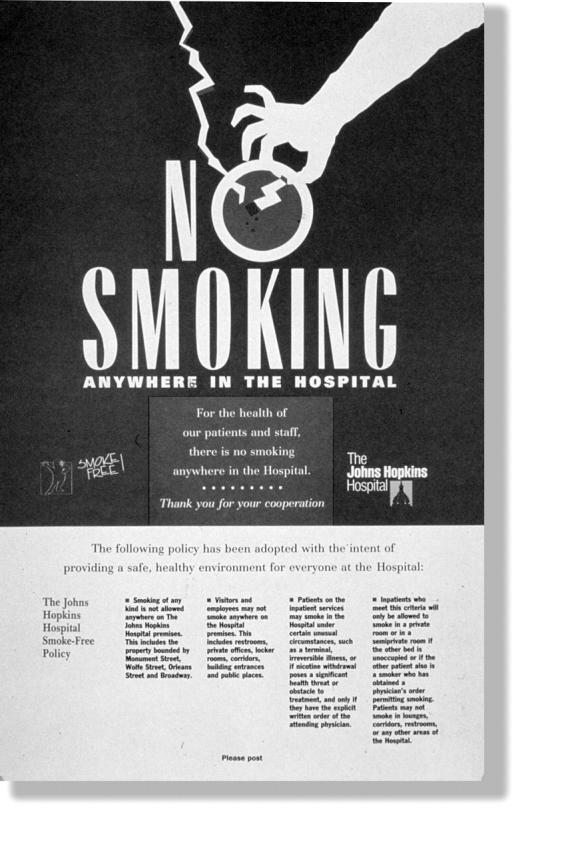

Figure 1.

Source. Prints and Photographs Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Md.

THIS 1990 POSTER FROM THE Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore proclaims the institution’s smoke-free policy in a clear and dramatic manner. The Hopkins Employee Handbook is even more forceful in its application of the policy to hospital staff. Failure to comply with the ban on smoking in a nondesignated area is a “critical violation” of the employee code of conduct, in the same category as deliberate inattention to patient care, the falsification of records, and the unauthorized possession of a deadly weapon.1 Disciplinary action, depending on the circumstances, will lead to suspension or immediate termination of employment.

Johns Hopkins’s stringent enforcement of a smoke-free policy for hospital staff was part of a national movement that gathered strength in the 1980s and accelerated in the early 1990s as hospitals around the country prepared to implement a new standard enacted by the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), effective December 31, 1993.2–4 By 1994, more than 96% of US hospitals complied with the new smoking ban standard and more than 41% had enacted policies that were even stricter.5,6

The effective implementation of JCAHO standards had set up a natural experiment; US hospitals were undergoing the first industry-wide ban on smoking in the workplace. Investigators soon discovered that the smoking ban—established to protect the health of patients—had not only transformed the environment of health care institutions but had also had a marked and salutary effect on the smoking behavior and thus the health of hospital workers. Compared with other workers in the same communities, hospital workers had a significantly higher rate of quitting smoking.7 This difference began with the smoking ban and continued for 5 years. Later studies found that the differences in quit ratios held up over time, although both sets of workers tended to relapse at the same rate.8 Antismoking advocates would thus like to see workplace smoking bans extended to all industries; they estimate that such a policy would cut overall smoking prevalence by 10% and have the greatest impact on groups with the highest smoking rates.5

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins Health System, Johns Hopkins Hospital. Employee handbook—represented employees. Critical violations. Available at: http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/jhhr/hbook_bu.htm. Accessed October 5, 2003.

- 2.Kales SN. Smoking restrictions at Boston-area Hospitals, 1990–1992: a serial survey. Chest. 1993;104:1589– 1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenista JA. Smoking policy in pediatric Hospitals and wards. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:567–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker AF, Moseley JR, Glidewell BL. Components of a smoke-free hospital program. Arch Intern Med. 1989; 149:1357–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longo DR, Feldman MM, Kruse RL, Brownson RC, Petroski GF, Hewett JE. Implementing smoking bans in American hospitals: results of a national survey. Tob Control. 1998;7:47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longo DR, Brownson RC, Kruse RL. Smoking bans in US hospitals: results of a national survey. JAMA. 1995;274:488–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longo DR, Brownson RC, Johnson JC, et al. Hospital smoking bans and employee smoking behavior: results of a national survey. JAMA. 1996;275: 1252–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longo DR, Johnson JC, Kruse RL, Brownson RC, Hewett JE. A prospective investigation of the impact of smoking bans on tobacco cessation and relapse. Tob Control. 2001;10:267–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]