Abstract

Objectives. We estimated the prevalence of overweight in a population of young children enrolled in a New York City Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Methods. Administrative and survey data were collected from a sample of enrolled families. Body mass index (BMI) of 557 children aged 2, 3, and 4 years was compared by sociodemographic and nutrition characteristics.

Results. Forty percent of the children were overweight or at risk for overweight (BMI ≥ 85th percentile). Compared with other racial/ethnic groups combined, Hispanic children were more than twice as likely (odds ratio = 2.6; 95% confidence interval = 1.8, 3.8) to be overweight or at risk for overweight. Two-year-olds were less likely to be overweight than 3- and 4-year-olds.

Conclusions. Interventions to address childhood overweight should be culturally specific and target very young children.

Overweight and obesity among both children and adults are increasing and, as a result, receiving greater attention. The recent release by the US Department of Health and Human Services of The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity is one indication of the recognition of obesity as a serious public health issue.1 National survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System show that the prevalence of obesity among adults increased from 12% in 1991 to 17.9% in 1998.2 Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggest that prevalence is actually closer to 23%,3,4 and preliminary results from the most recent NHANES show a further increase, to 31%.5

NHANES data also show an increase in overweight among children aged 6 to 11 from 4% of the population in 1971 through 1974 to 15% in 1999 through 2000, and a corresponding increase among children aged 2 to 5 years from 5% to 10%.6 Another analysis looking at overweight in preschool children found the prevalence of overweight in 1994 to be 3% among 2- and 3-year-olds and 8% among 4- and 5-year-olds, which represented an increase over 20 years among children aged 4 to 5 years but not among those aged 2 to 3 years.7 Additionally, among children participating in the Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System (which monitors the nutritional status of low-income children in federally funded nutrition and maternal and child health programs), the prevalence of overweight increased from 7% in 1989 to 8.6% in 1997.8

The adverse health effects of overweight and obesity have been well established. In adults, obesity is associated with a number of health problems, including type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.4 Health problems associated with overweight in childhood include high blood pressure, high cholesterol, orthopedic disorders, and pyschosocial disorders.9–11 Type 2 diabetes, linked with overweight and obesity, is on the rise in children as well.12,13 Other research has highlighted the link between overweight in childhood and obesity in adulthood: overweight children are more likely to become overweight and obese adults.14–16

Although it is clear that the prevalence of childhood overweight is increasing and represents a serious health risk, the extent of the problem in very young children is less clear. Much of the research surrounding childhood overweight has focused on children over age 5. But early recognition and prevention efforts are key in addressing public health issues, and for some children, age 5 may already be too late.

Medical and Health Research Association of New York City, Inc (MHRA) and the MHRA New York City Neighborhood Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC Program) undertook a study to determine the level of acceptance of WIC educational messages about milk and fruit/vegetable consumption among participants and their families. The study also looked at levels of overweight and obesity. This paper describes the portion of the study examining the prevalence of overweight among children aged 2 to 4 years enrolled in this WIC program, with the goal of describing the extent and the distribution by age and race/ethnicity of overweight in this population.

METHODS

The New York City Neighborhood WIC Program, the largest WIC provider in New York City, with 18 sites, offers food assistance and nutrition education to a low-income, racially and ethnically diverse population, serving more than 50 000 women, infants, and children each year. (MHRA is one of 47 agencies throughout New York City that, all together, serve approximately 360 000 participants annually at roughly 134 sites.)

In this cross-sectional study, all families enrolling or recertifying to continue their enrollment in the MHRA WIC program during 1 week in February 2001 were asked to complete a brief anonymous questionnaire including questions on family diet and exercise habits, racial/ethnic identification, and ancestry. The questionnaire was available in 7 different languages predominantly used by this population. A total of 1255 families completed questionnaires at the 18 MHRA WIC sites, which are distributed throughout 4 of New York City’s 5 boroughs, primarily in low-income neighborhoods.

Height and weight had been measured at recent visits (within the prior 60 days) to a medical provider—with anthropometrics reported on forms filled out by the medical provider—or were measured by WIC staff on the day of the visit. Administrative data from certification forms were collected for each family member enrolling or recertifying that day. WIC staff attached each certification form to the corresponding family questionnaire, then removed personal identifiers from the form.

Data from the certification forms, including sex, date of birth, height, and weight, were in this way matched to family information on type of milk consumed, fruit/vegetable consumption, and a crude measure of exercise. However, because only 1 questionnaire was completed by each family, individual-level anthropometrics were not matched to individual-level nutrition data but to family-level nutrition data. The resulting sample was composed of 1443 individual family members, including 556 children aged 2 to 4 years.

Body mass index (BMI) has been generally accepted as a screening measure for obesity in adults and is becoming widely used for adolescents and children as well, having proven to be a fairly reliable indication of adiposity, correlating with measures of total body fat.17,18 For the children in our sample, BMI was calculated and compared to the sex-specific BMI-for-age reference percentiles issued by the National Center for Health Statistic of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.19 Following the standards issued with the BMI growth charts by the National Center for Health Statistics, a BMI greater than or equal to the 95th percentile indicates overweight, a BMI greater than or equal to the 85th percentile but less than the 95th percentile indicates risk for overweight, a BMI greater than or equal to the 5th percentile and less than the 85th percentile indicates normal weight, and a BMI less than the 5th percentile indicates underweight.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed with SPSS statistical software version 9.0.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). Statistical differences in BMI among demographic groups were assessed using χ2 tests. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the relationships between demographic variables and outcome variables. Using logistic regression, adjusted ORs and 95% CIs were calculated with BMI categories as the dependent variables, adjusting for race/ethnicity (White, Hispanic, Black, Asian), age (3 to 4 years old, 2 years old), sex (girl, boy), birthplace of the parent filling out the questionnaire (US born, foreign born), type of milk consumed by children in family (2%/1%/fat free, whole), fruit/vegetable consumption (at least once a day, less than once a day), and exercise (at least twice a week, less than twice a week).

RESULTS

The sample was evenly divided between boys and girls and between 2-, 3-, and 4-year-olds. Of the 556 children aged 2 to 4 years, 49% were female, 35% were 2 years old, 37% were 3 years old, and 28% were 4 years old. The population served by the MHRA New York City Neighborhood WIC Program is largely Hispanic, and that was reflected in the racial/ethnic distribution of this sample: 59% were Hispanic, 19% Black, 10% Asian, and 8% White. The 4 largest Hispanic groups were Mexicans (25%), Dominicans (24%), Puerto Ricans (16%), and Ecuadorians (16%). Although this is not representative of the US population, or even that of New York City, it is representative of the MHRA New York City Neighborhood WIC Program population.

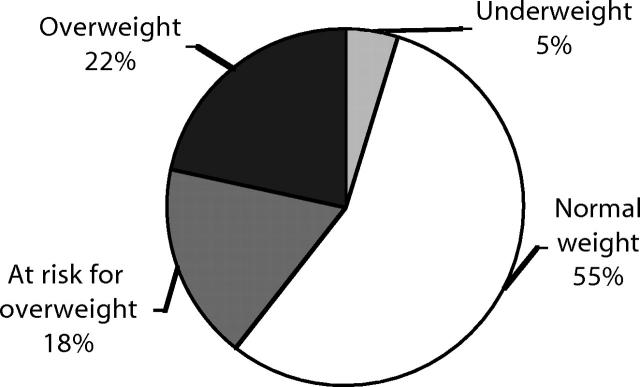

A full 40% of these children were overweight or at risk for overweight (Figure 1 ▶): 22% were overweight, and 18% were at risk for overweight. Table 1 ▶ shows the proportion of children who were overweight by demographic group. No difference was found between boys and girls with respect to percentage overweight or at risk for overweight. However, a significant difference was found in the percentage overweight by age: whereas 14% of 2-year-old children were overweight, more than 25% of 3- and 4-year-old children were overweight (P = 0.05). Furthermore, when BMI percentiles were examined for 6-month age groups, it became apparent that the increase in overweight began at about age 2 and one-half years—only 8% of children aged 24 to 29 months were overweight, but 19% of children aged 30 to 35 months were overweight.

FIGURE 1—

Weight status of children aged 2 to 4 years enrolled in a New York City WIC program: 2001.

Note. Categories based on the body mass index growth charts of the National Center for Health Statistics.19 The definitions are as follows: overweight: ≥ 95th percentile; at risk for overweight: ≥ 85th and < 95th percentile; normal weight: ≥ 5th and < 85th percentile; underweight: < 5th percentile.

TABLE 1—

Weight Status of Children Aged 2 to 4 Years Enrolled in a New York City WIC Program: 2001

| Overweight,a No. (%) | At Risk for Overweight,b No. (%) | Normal Weight,c No. (%) | Underweight,d No. (%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Boy | 69 (24.6%) | 45 (16.0%) | 153 (54.4%) | 14 (5.0%) |

| Girl | 52 (19.3%) | 52 (19.3%) | 153 (56.7%) | 13 (4.8%) |

| Age, y | ||||

| 2 | 27 (14.0%) | 33 (17.1%) | 123 (63.7%) | 10 (5.2%) |

| 3 | 53 (26.1%) | 35 (17.2%) | 104 (51.2%) | 11 (5.4%) |

| 4 | 41 (26.5%) | 29 (18.7%) | 79 (51.0%) | 6 (3.9%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 83 (26.7%) | 70 (22.5%) | 152 (48.9%) | 6 (1.9%) |

| Black | 14 (13.7%) | 16 (15.7%) | 65 (63.7%) | 7 (6.9%) |

| Asian | 12 (21.8%) | 5 (9.1%) | 31 (56.4%) | 7 (12.7%) |

| White | 5 (10.9%) | 2 (4.3%) | 35 (76.1%) | 4 (8.7%) |

| Total | 121 (22.0%) | 97 (17.6%) | 306 (55.5%) | 27 (4.9%) |

Note. BMI = body mass index.

aBMI: ≥ 95th percentile.

bBMI: ≥ 85th and < 95th percentile.

cBMI: ≥ 5th and < 85th percentile.

dBMI: < 5th percentile.

Significant differences in percentage overweight were found among racial/ethnic groups as well. Twenty-seven percent of Hispanic children, 14% of Black children, 22% of Asian children, and 11% of White children were overweight (P < 0.001). When compared to the other racial/ethnic groups combined, Hispanic children were twice as likely (OR = 2.1; 95% CI = 1.3, 3.3) to be overweight; they were more than twice as likely (OR = 2.6; 95% CI = 1.8, 3.8) to be overweight or at risk for overweight. No differences were observed among Hispanics of various ancestry.

Additional analyses revealed that 73% of the children resided in families where whole milk was drunk by children aged 2 years and older; of those families, only 30% had tried low-fat milk. An additional 12% drank 2% milk, 8% drank 1% or fat-free milk, and 56% ate any fruits/vegetables at least once a day. Although many parents (82%) reported that their children exercise at least twice a week, the question allowed for a loose interpretation of exercise.

In a multivariate logistic regression model (Table 2 ▶), including race/ethnicity, age, sex, birthplace of parent, type of milk consumed by children in the family, fruits/vegetables consumed by children in the family, and exercise by children in the family (all reported by parents), Hispanic children remained significantly more likely to be overweight or at risk for overweight (adjusted OR = 3.4; 95% CI = 1.4, 8.4). In addition, 2-year-olds remained significantly less likely than 3- and 4-year-olds to be overweight or at risk for overweight (adjusted OR = 0.64; 95% CI = 0.42, 0.98). Children whose parent was born outside of the United States were also more likely to be overweight or at risk for overweight (adjusted OR = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.1, 2.9). The majority (77.2%) of Hispanic and virtually all Asian parents were foreign born. Finally, children in families drinking whole milk were significantly less likely to be overweight or at risk for overweight (adjusted OR = 0.50; 95% CI = 0.31, 0.80). This may indicate that families with overweight children have been exposed to a health message regarding decreased whole-milk consumption.

TABLE 2—

Logistic Regression Analyses: Distributions and Adjusted Odds Ratios for Factors Associated With Childhood Overweight and Risk for Overweight: 2001

| No. | Overweight or at Risk for Overweighta | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Sex | |||

| Boy | 240 | 41% | 1.10 (0.73, 1.64) |

| Girl | 211 | 38% | Ref. |

| Age | |||

| 2 years | 163 | 31% | 0.64 (0.42, 0.98)* |

| 3 or 4 years | 288 | 44% | Ref. |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 281 | 49% | 3.44 (1.42, 8.35)** |

| Black | 91 | 29% | 1.53 (0.58, 4.06) |

| Asian | 43 | 28% | 1.14 (0.37, 3.47) |

| White | 36 | 15% | Ref. |

| Parent born in United States | |||

| No | 316 | 44% | 1.79 (1.10, 2.90)* |

| Yes | 135 | 28% | Ref. |

| Exercise twice a week or moreb | |||

| No | 74 | 34% | 0.83 (0.48, 1.45) |

| Yes | 377 | 40% | Ref. |

| Type of milk consumedb | |||

| Whole milk | 350 | 34% | 0.50 (0.31, 0.80)** |

| 2%, 1%, or fat free | 101 | 58% | Ref. |

| Fruits/vegetables consumedb | |||

| Less than once a day | 204 | 41% | 1.28 (0.85, 1.93) |

| Once a day or more | 247 | 37% | Ref. |

aOverweight or at risk for overweight defined as body mass index ≥ 85th percentile.

bAs reported by parents for all children in family

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

The same trends were evident in a similar regression model with proportion overweight as the dependent variable. However, in the second model, age and milk consumption were the only predictors that remained significant.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that a large proportion of young children in a New York City WIC population were overweight or at risk for overweight. Hispanic children, who made up the majority of this population, and 3- to 4-year-old children were most likely to be overweight or at risk for overweight. The finding that children in 73% of families drank whole milk and children in 44% of families ate fruits/vegetables less than once a day indicates that the nutrition and health habits of the families surveyed did not, in general, meet current recommendations.

There are some limitations to these data and the conclusions that can be drawn from them. These are cross-sectional data and provide point prevalence only. In addition, this is not an unbiased sample; this is a high-risk population, and excessive weight for stature is one of the nutritional risk factors that qualifies a child for WIC. Measurement bias is also a possibility: data on whether the heights of 2-year-olds were measured in a recumbent or standing position were not available. Although WIC policy is to begin measuring children standing at age 2 years, it is possible that some of the 2-year-olds were measured in a recumbent position, which could serve to overestimate the level of overweight among 2-year-olds.20

There are also several potential concerns related to the measurement of nutrition and health habits. Parents, particularly those who may have been told that their children are overweight, may have given what they deemed the expected or socially desirable response to these questions. This would tend to attenuate the effect of these habits on overweight status and may help explain why the effect we see of whole-milk consumption on overweight is in the opposite direction from that expected. In addition, we do not know the amount of milk drunk by these children. We also did not measure juice consumption; juice may or may not have been considered by parents in the children’s fruit/vegetable count. Finally, the poor nutrition and health habits uncovered in this survey can be linked only indirectly to the level of overweight among the children. BMI is an individual measure, and although a child’s BMI was linked to the health and nutrition data collected for that child’s family, it could not be linked to specific nutritional information about that child.

Despite these limitations, the sizable increase in percentage overweight between age 2 and age 3 years is compelling. The high prevalence of overweight in this population is also of concern. WIC comprises a large population of children whose health status deserves attention. It is estimated that 45% of all infants born in the United States are served by WIC at some time, and, nationwide, an average of 3.67 million children aged 1 to 4 years participate in WIC each month.21 The 18% overweight among 2- to 4-year-olds in this New York City WIC population is higher than the already elevated 13.6% overweight among 2- to 4-year-olds in the national WIC population.22

Most prevalence surveys of childhood overweight find that overweight is higher among Hispanics than among non-Hispanic Whites or Blacks.2,4,6,7 This study was no exception. Almost 60% of the population in this study was Hispanic, and close to 50% of the Hispanic children were overweight or at risk for overweight. The proportion of Hispanic children in this population is larger than in other study populations, which may help explain the high prevalence of overweight found in this study; however, the proportion of Hispanic children in this population who are overweight is also greater than that of other Hispanic populations.

The data do not provide a clear picture of why the proportion is so high among Hispanics in this population; this question deserves further study. Because the Hispanic population is growing, both in the United States and in New York City, addressing the issue of childhood overweight in this population is of increasing consequence. However, it is important to remember that the Hispanic population is not monolithic. The Hispanics in this WIC population report ancestry from 17 different countries, and although their levels of childhood overweight were similar, their cultural heritages and diets are not. Interventions will need to be culturally specific and sensitive if they are to be effective.

The findings of this study also suggest that interventions should target very young children and their parents. The increase of overweight after age 2 years indicates a window of opportunity at age 2—a chance to initiate healthy eating habits and prevent overweight before it becomes a problem. Although this needs further investigation, it may be no accident that the increase in overweight occurs about the same time that most children are beginning to eat family meals. Families may need greater guidance in establishing healthy eating habits for their young children.

The association found between overweight and consumption of lower-fat milk may indicate that families are heeding—or are at least aware of—nutritional messages being promoted by WIC and other sources. WIC has the potential to play an even larger role here, but WIC’s historical programmatic focus on underweight as opposed to overweight could hamper these efforts.

Although this study did not include a non-WIC control group and, thus, could not explore the effect of WIC supplements on overweight, the WIC food prescriptions do not include many low-fat options. However, a shift in thinking about program goals and recent changes in the program at the federal level may give WIC nutritionists greater leeway to create food packages that address the problem of overweight and complement their nutritional counseling.

Addressing the problem of childhood overweight will also require targeting both diet and physical activity, both important components of a healthy lifestyle. For children aged 2 to 4 years, the parents and the home environment exert a strong influence on the development of childhood overweight.23 They are vital in forming current diet and physical activity habits as well as to setting patterns for the future.24–27

However, more research is necessary if we are to really understand the links between health behaviors—on the parts of both parents and children—and childhood overweight. It is important to understand, for example, who is taking care of the children during the day, who is making the food choices, what types and amounts of food they eat, what their actual levels of physical activity are, and how much time they spend watching television.28,29

The answers to these questions also may help explain the differences in overweight by race/ethnicity and age that we observed in this study. Understanding these links is crucial to developing effective interventions to prevent childhood overweight beginning at an early age. Given the serious health consequences and the increasing prevalence, this is an important public health goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff at all 18 MHRA New York City Neighborhood WIC Program sites for their assistance in collecting data.

Human Participant Protection This study was exempt from institutional review board review. The data were collected anonymously from adults. In addition, the study collected information that had a quality assurance function for the MHRA New York City Neighborhood WIC Program.

Contributors J. A. Nelson assisted with study design, analyzed the data, and wrote the article. M. A. Chiasson supervised data analysis and interpretation. Both M. A. Chiasson and V. Ford were responsible for study conception and design, and contributed to the writing of the article.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Office of the Surgeon General. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [PubMed]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991–1998. JAMA. 1999;282:1519–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eberhardt MS, Ingram DD, Makuc DM, et al. Health, United States, 2001 with Urban and Rural Health Chartbook. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001:256 [Table 69]. DHHS Publication (PHS) 01-1232.

- 4.Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1723–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1728–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogden CL, Troiano RP, Briefel RR, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Johnson CL. Prevalence of overweight among preschool children in the United States, 1971 through 1994. Pediatrics. 1997;99:E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance, 1997 Full Report. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1998:14.

- 9.Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 pt 2):518–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relationship of childhood obesity to coronary heart disease risk factors in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2001;108:712–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gidding SS, Leibel RL, Daniels S, Rosenbaum M, Van Horn L, Marx GR. Understanding obesity in youth. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Atherosclerosis and Hypertension in the Young of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and the Nutrition Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996;94:3383–3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinhas-Hamiel O, Zeitler P. Type 2 diabetes: not just for grownups anymore. Contemp Pediatr. 2001;18:102–125. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenbloom AL, Joe JR, Young RS, Winter WE. Emerging epidemic of type 2 diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serdula MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Byers T. Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature. Prev Med. 1993;22:167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:869–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo SS, Chumlea WC. Tracking of body mass index in children in relation to overweight in adulthood. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:145S–148S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietz WH, Bellizzi MC. Introduction: the use of body mass index to assess obesity in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:123S–125S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Obesity evaluation and treatment: Expert Committee recommendations. The Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration and the Department of Health and Human Services. Pediatrics. 1998;102:E29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000 CDC growth charts: United States. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/. Accessed August 26, 2003.

- 20.Lampl M, Birch L, Picciano MF, Johnson ML, Frongillo EA Jr. Child factor in measurement dependability. Am J Human Biol. 2001;13:548–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Agriculture, Food & Nutrition Service. Women, infants, and children [WIC Program webpage]. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/. Accessed August 26, 2003.

- 22.Cole N. The Prevalence of Overweight Among WIC Children. Cambridge, Ma: Abt Associates, Inc; 2001:15. WIC General Analysis Project: WIC Participant Monograph Series.

- 23.Strauss RS, Knight J. Influence of the home environment on the development of obesity in children. Pediatrics. 1999;103:e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klesges RC, Stein RJ, Eck LH, Isbell TR, Klesges LM. Parental influence on food selection in young children and its relationships to childhood obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliveria SA, Ellison RC, Moore LL, Gillman MW, Garrahie EJ, Singer MR. Parent-child relationships in nutrient intake: the Framingham Children’s Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:593–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sallis JF, Nader PR, Broyles SL, et al. Correlates of physical activity at home in Mexican-American and Anglo-American preschool children. Health Psychol. 1993;12:390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson SL, Birch LL. Parents’ and children’s adiposity and eating style. Pediatrics. 1994;94:653–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spruijt-Metz D, Lindquist CH, Birch LL, Fisher JO, Goran MI. Relation between mothers’child-feeding practices and children’s adiposity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dennison BA, Erb TA, Jenkins PL. Television viewing and television in bedroom associated with overweight risk among low-income preschool children. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1028–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]