Abstract

Flint Photovoice represents the work of 41 youths and adults recruited to use a participatory-action research approach to photographically document community assets and concerns, critically discuss the resulting images, and communicate with policymakers.

At the suggestion of grassroots community leaders, we included policymakers among those asked to take photographs. In accordance with previously established photovoice methodology, we also recruited at the project’s outset another group of policymakers and community leaders to provide political will and support for implementing photovoice participants’ policy and program recommendations.

Flint Photovoice enabled youths to express their concerns about neighborhood violence to policymakers and was instrumental in acquiring funding for local violence prevention. We note salutary outcomes produced by the inclusion of policymakers among adults who took photographs.

“PHOTOVOICE” IS A participatory-action research methodology based on the understanding that people are experts on their own lives.1,2 It was first tried among village women in Yunnan Province, China.3 Using the photovoice methodology, participants allow their photographs to raise the questions, “Why does this situation exist? Do we want to change it, and, if so, how?” By documenting their own worlds, and critically discussing with policymakers the images they produce, community people can initiate grassroots social change.4

In practice, photovoice provides people with cameras so they can record and represent their everyday realities. It uses those pictures to promote critical group discussion about personal and community issues and assets. Finally, it is designed to reach—and touch—policymakers. By having people who live in the community take photographs and describe the meaning of their images to policymakers and community leaders, photovoice embraces the basic principles that images carry a message, pictures can influence policy, and citizens ought to participate in creating and defining the images that make healthful public policy.5 Photovoice combines a community-based approach to photography and health promotion principles, built on the theoretical understandings established in the literature on education for critical consciousness and feminist theory.1,2

Adopting Paulo Freire’s approach to education for critical consciousness,6,7 photovoice participants consider, and seek to act upon, the historical, institutional, social, and political conditions that contribute to personal and community problems. Photovoice draws from a position in feminist theory described by art historian Griselda Pollock in which “Everyone has a specific story, a particular experience of the configurations of class, race, gender, sexuality, family, country, displacement, alliance. . . . Those stories are mediated by the forms of representation available in the culture.”8(xv) The photovoice methodology expands the forms of representation and the diversity of voices who help define, and improve, our social, political, and health realities.

METHODS

The impetus for Flint Photovoice came from the leadership of the Neighborhood Violence Prevention Collaborative, a coalition of 265 neighborhood groups and block clubs in Flint, Mich. The people of Flint and Genesee County have struggled with the transition from being a one-industry town heavily dependent on automobile manufacture to redefining the community’s economy, culture, race relations, and well-being; many of these challenges may be similar to those of other urban communities. A core group of 8 local facilitators were recruited to lead Photovoice workshops with participants. In addition, 11 professional photographers from Genesee County mentored participants in the use of Holga cameras (name of manufacturer and location in People’s Republic of China unknown) with black-and-white film. We chose the Holga camera because it is relatively inexpensive (approximately US $20) and offers users the creative option of taking double and multiple exposures, literally layering meanings.

Facilitators and professional photographers participated in a train-the-trainers session, during which they were introduced to the photovoice concept and methods and were given examples of how village women in rural China, homeless people in Ann Arbor,9 and families in the San Francisco Bay area10 have applied photovoice to reach policymakers. Facilitators and photographers discussed power, ethics, and the use of cameras and went on a guided photo shoot to practice using the camera. They then applied this session model with subsequent project participants.

Photographs and narratives were produced by 4 groups: 10 youth participants in the National Institute for Drug Abuse– supported Flint Adolescent Study; 10 youths active in community leadership roles; 11 adult neighborhood activists; and 10 local policymakers and community leaders. The photovoice methodology specifies, at the project’s outset, the recruitment of policymakers and community leaders, not to take pictures but rather to provide the political will to support and help implement Photovoice participants’ policy and program recommendations. We recruited a Guidance Committee of policymakers and community leaders for this purpose. At the suggestion of the Neighborhood Violence Prevention Collaborative’s leadership, however, we modified the photovoice methodology by asking an additional group of policymakers and community leaders to take photographs. Taken together, the participants were diverse in age, income, experience, neighborhood, and social power.

At subsequent workshops, participants were first asked to do “freewrites” about the 1 or 2 photographs from each roll of film that they felt to be most important or simply liked best. These questions were set around the mnemonic “SHOWeD”: What do you See here? What is really Happening? How does this relate to Our lives? Why does this problem or strength exist? What can we Do about it? Participants then presented their photographs and freewrites to the group to spark critical dialogue.

Photovoice participants codify issues, themes, or theories that emerge from the group discussion of photographs. In Flint Photovoice, themes arose from participants’ monthly group discussions in a consensus-building process involving all attending the meetings. We defined a “theme” as having at least 4 compelling photographs and stories that emerged during group discussion.

DISCUSSION AND EVALUATION

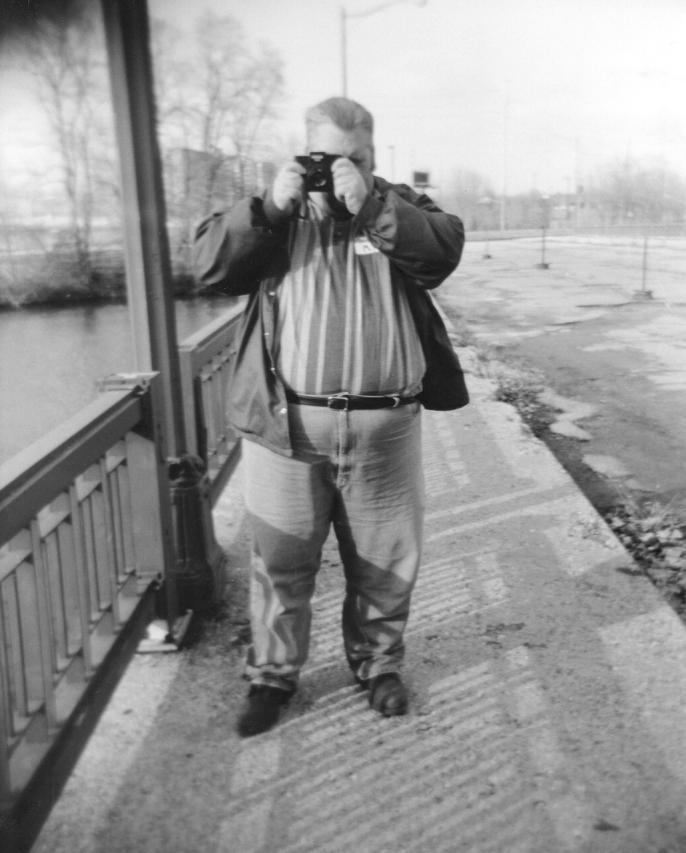

At invited forums, participants presented their concerns to policymakers, community leaders, donors, the media, and the general public. One participant photographed her husband standing on a bridge taking a picture of her (Figure 1 ▶). The bridge is the same one where Flint citizens gathered to conduct a public burning of Money magazine when it named Flint the worst US city in which to live in 1987. The title of the image, Looking Back at You While You Are Looking Back at Me, suggests how participants wished to redefine how the community saw itself: not as one ridiculed by Money magazine’s ranking and Michael Moore’s popular independent film Roger and Me, but as a community concerned about public health, the quality of neighborhoods, economic development, religion, racism, and youth opportunities—the 6 themes participants identified in the Photovoice process.4

FIGURE 1—

Looking Back at You While You Are Looking Back at Me. Photograph by Cynthia Parkin, Flint, Mich, 1999.

An iconic photograph entitled Exploded Frustration (Figure 2 ▶), taken by Eric Dutro, a 17-year-old participant, featured a bullet hole on his bus. Eric wrote, “I can tell that the bus I ride in is always different because the bullet holes are always in different windows.” His images and words were shared widely with policymakers, journalists, and health officials locally and nationally.

FIGURE 2—

Exploded Frustration. Photograph and text by Eric Dutro, Flint, Mich, 1999.

“Violence. The line of the snow and concrete dividing the bullet hole shows that there are two sides to every story—a person with a gun and demands and a person with fear and a wallet. I am going to school. I can tell that the bus I ride in is always different because the bullet holes are always in different windows. This is rather disturbing. Many people use public transportation, which should not be a place where you should be scared. Not that riding the bus is scary, but the bullet holes are cold reminders that you never know what will happen next. This violence exists because people don’t know how to deal with hardships and anger. They think it’s easier to rob people for money or shoot when they are scared. But in the long run, it is much harder. We need to give people positive confidence somehow. Show them that they have special skills and help them find out what their gifts are. Once they believe that they are not victims of circumstance and they can determine their destiny, they will find this strength many times more powerful than a gun.”

While tracking the effects of Photovoice on policy and program decisions is challenging, to date Flint Photovoice has been instrumental in successful competition for a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–supported Youth Violence Prevention Center in Flint. As a result of the project, the community-based and university grant partners achieved a deeper understanding of neighborhood safety and violence issues from the perspective of young people. Flint Photovoice also has engaged youths directly in expressing their concerns about neighborhood safety and violence to Flint’s mayor and other community leaders, and contributed to the renewal of funding for Genesee County programs (A. Richards, Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, oral communication, 2003).

Policymakers’ and community leaders’ participation as photographers offered several advantages. First, they took it upon themselves to provide venues, such as legislative breakfasts, city hall, the health department, and news programs, at which to present themes culled from all participants’ efforts. Although the responsibility to secure such venues normally falls primarily on the Guidance Committee of policymakers recruited for this purpose, the picture-taking policymakers significantly invigorated this effort. Second, their firsthand experience with photovoice gave them an innovative tool with which to explore and improve the programs over which they exert the most influence. For example, the county health department director’s experience as a Photovoice participant resulted in his introducing the methodology for an ongoing gonorrhea control initiative focused on tapping staff and consumer insight.

Third, their participation set the stage for interactions in which people representing widely disparate ages, incomes, experience, neighborhoods, and social power no longer saw one another as inaccessible and lacking common ground, but as approachable fellow human beings. We anticipate that one of the most powerful outcomes of Flint Photovoice will continue to emerge in the long-term relationships built among these diverse participants who, having shared a memorable community assessment experience, newly appreciate and draw upon one another’s expertise for future efforts to address public health, quality of neighborhoods, economic development, faith-based health initiatives, racism, and youth opportunities.

KEY FINDINGS.

Flint Photovoice was instrumental in successful competition for a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–supported Youth Violence Prevention Center in Flint, Mich, and contributed to a foundation’s renewal of funding for Genesee County programs.

As a result of recruitment of policymakers to take photographs, policymakers offered venues for highly visible forums featuring all participants’ work and acquired experience with a methodology they could adapt for future community health programs.

Community building was facilitated through the participation in the photovoice process of people differing widely in age, income, experience, neighborhood, and social power.

Acknowledgments

Flint Photovoice was made possible through the generous support of The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. The Prevention Research Center of Michigan, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, also provided support.

We are grateful to Marc Zimmerman and Ann Richards for valuable advice. We thank Karen Aldridge Eason, Barbara Inwood, Lisa Powers, and Yanique Redwood-Jones for their leadership in carrying out Flint Photovoice, and the facilitators, photography mentors, and Guidance Committee members for their many contributions. We are grateful to Peter Solomon, Fong Wang, and the reviewers for editorial suggestions. Most of all, we thank the youth, adult, and policymaker participants for their dedication and insights.

Contributors C. C. Wang directed the project and drafted the article. S. Morrel-Samuels codirected the project. P. M. Hutchison and L. Bell led the project’s community-based design and implementation. A policymaker participant, R. M. Pestronk provided a public health practice perspective for the article. All authors contributed revisions to the article.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Wang C, Burris M, Xiang Y. Chinese village women as visual anthropologists: a participatory approach to reaching policymakers. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:1391–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang C, Burris M. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu K, Burris M, Li V, et al., eds. Visual Voices: 100 Photographs of Village China by the Women of Yunnan Province. Yunnan, China: Yunnan People’s Publishing House; 1995.

- 4.Wang CC, ed. Strength to Be: Community Visions and Voices. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2001.

- 5.Wang CC. Photovoice as a participatory action research strategy for women’s health. J Womens Health. 1999;8:185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freire P. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York, NY: Continuum; 1973.

- 7.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:379–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollock G, ed. Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts. London, England: Routledge; 1996.

- 9.Wang CC, Cash JL, Powers LS. Who knows the streets as well as the homeless? Promoting personal and community action through photovoice. Health Promot Pract. 2000;1:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spears L. Picturing concerns: the idea is to take the messages to policy makers and to produce change. Contra Costa Times. 11April1999:A27, A32. [Google Scholar]