Abstract

Objectives. Complementary and alternative therapies have become popular with patients in Western countries. Studies have suggested motivations for patients’ choosing a wide range of complementary therapies. Data on the expectations of patients who use complementary therapy are limited. We assessed the expectations of patients who use complementary therapy.

Methods. Patients attending a British National Health Service (NHS) outpatient department that provided acupuncture, osteopathy, and homoeopathy were asked to complete a qualitative survey.

Results. Patients expected symptom relief, information, a holistic approach, improved quality of life, self-help advice, and wide availability of such therapies on the NHS.

Conclusions. Physicians’ understanding of patients’ expectations of complementary therapies will help patients make appropriate and realistic treatment choices.

The use of complementary therapies has been reported in a number of studies.1–6 Thomas et al.7 estimated that patients made 22 million visits to practitioners of at least 1 of 6 established therapies in 1998 in the United Kingdom. Reasons for patients’ choosing complementary therapies are diverse8 and include ineffectiveness of orthodox medicine, concern about the adverse effects of orthodox medicine, poor patient–physician communication, and the increasing availability of complementary therapy.9,10 Although attempts have been made through surveys to examine the extent of, use of, and reasons for referral to complementary therapy, few surveys have elicited the expectations of patients. In 1 small, unpublished study, researchers found that although most patients sought a cure or improvement in their condition, they also were looking for hope, reassurance, explanations, advice, and understanding.11

Because expectations of both practitioner and patient influence the outcome of an intervention, understanding the expectations of patients and clarifying the limitations of treatment are important.11 Patients who are dissatisfied with conventional treatment may have high expectations of complementary therapies. Such expectations, particularly in the context of chronic illness, may be unreasonable, thus leading to dissatisfaction with the complementary therapy. Conversely, dissatisfaction with conventional treatment might lead to low expectations for any other form of intervention and, therefore, a patient’s inflation of the outcome of treatment of the complementary therapy. An understanding of patient expectations is particularly relevant in regard to non-Western therapies grounded in different theories. These therapies, which are often based on a long and detailed patient assessment aimed at addressing health problems at a deep level, can involve lifestyle changes. For patients expecting a quick fix, the complementary therapy approach could present a challenge that may have an adverse effect on compliance or follow-up. Alternatively, patients may find conventional treatments to be limited and may desire a “holistic” approach that enables them to search for meaning in their illness.12

Qualitative research methods are appropriate for new fields of study or for settings in which the experiences of individuals are of concern to policymakers.13 These methods provide rich descriptions of what it is like to experience illness or suffering14 and should be an essential component of health services research.15 I used a qualitative survey approach to examine the expectations of patients who were treated at a British National Health Service (NHS) complementary therapy outpatient center.

METHODS

Setting

The study setting was an NHS complementary therapy clinic that provided outpatient acupuncture, osteopathy, and homoeopathy. All patients were referred to the clinic through a letter from their general practitioner (GP) or a hospital consultant.16 Patients did not pay for their treatment.

Participants

Study participants were all patients (n = 327) treated at the complementary therapy clinic during a 9-month period. Patients younger than 16 years of age at referral were excluded.

Procedure

Before treatment, patients received a self-assessment health questionnaire patterned on the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36).17 The SF-36, a self-completed questionnaire based on a multidimensional model of health, focuses on 8 health concepts believed to be representative of basic human values and relevant to every individual’s functional status and well-being. These concepts can be condensed into 4 discrete areas: behavioral functioning, perceived well-being, social and role disability, and personal evaluation. In addition to eliciting self-assessed health status, the questionnaire also invited patients to record qualitative comments about their expectations of complementary therapy. Patients were asked an open-ended question: “What do you expect from the [complementary therapy] service?” They were requested to return the questionnaire to the hospital research unit in a postage-paid envelope.

RESULTS

Of the 327 patients surveyed, 237 (72.5%) returned the questionnaire; 86% of these recorded qualitative statements regarding their expectations of complementary therapy.

Data Analysis

Data from referral letters were used to assess patients’ demographic and disease characteristics. Patients’ conditions were classified according to the primary diagnosis provided in the referral letter and to The International Classification of Primary Care in the European Community.18

Data analysis of responses to the questionnaire was performed through thematic analysis with Framework,19 a method of qualitative analysis that involves a 4-stage process and includes mechanisms for ensuring trustworthiness (validity) of the data.20 In the first stage, the researcher read the patient comments twice to become familiar with the data, then searched for and noted main points. In the second stage, a framework was constructed to index (code) the data. Comments were read with particular attention to the issues arising from the first stage. The question of validity in qualitative research is particularly relevant during data categorization. Burnard21 proposed a method for checking validity that consists of asking a colleague who is not involved in the study but who is familiar with qualitative research and the process of thematic analysis to read the text and identify a category system. If the colleague’s themes are similar to those of the original researcher, there is a strong possibility that the original thematic system is valid.20 This was the approach used in this study, and the themes identified by the researcher were similar to those identified by the researcher’s colleague. The third stage of the data analysis involved an indexing process wherein the data was coded according to the developed thematic framework. The final stage, mapping and interpretation, consisted of summarizing key characteristics of the data and interpreting the data set as a whole. Quoted comments from patients were selected to represent the breadth and depth of the themes and are reported nearly verbatim.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

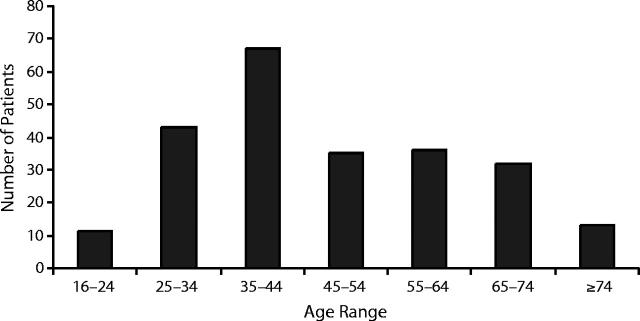

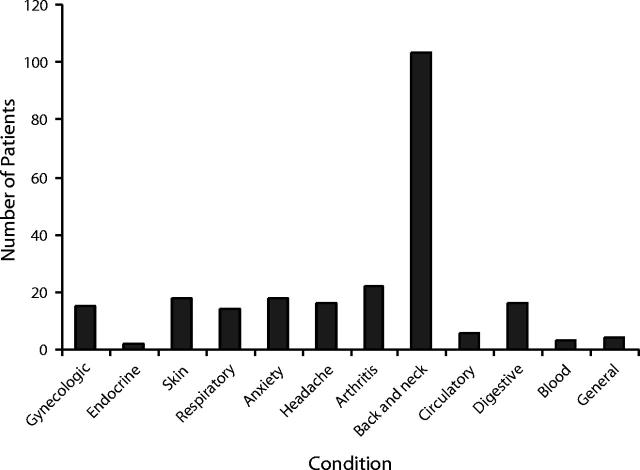

Of the 237 patients who returned questionnaires, 69 (29%) were male and 168 (71%) were female. One hundred eighteen (50%) of the patients were referred for acupuncture, 71 (30%) for osteopathy, and 48 (20%) for homoeopathy. Figure 1 ▶ shows the age distribution of patients treated during the study period. Figure 2 ▶ provides a breakdown of the conditions for which patients were referred for treatment, of which musculoskeletal (back and neck) problems were the most frequent.

FIGURE 1—

Age distribution of survey participants.

FIGURE 2—

Conditions for which patients were referred for treatment.

These conditions are similar to those reported in the literature.22,23 The age distribution in this study differs from that reported in Thomas et al.7 There may be a number of reasons for this difference. Thomas et al. surveyed a much larger sample than was surveyed in this study, and their study included a wider range of therapies. However, in this study all of the treatment was funded by the NHS, whereas only 10% of the treatment in the study reported by Thomas et al. was funded by the NHS. The demographic characteristics of patients treated with complementary therapies within the NHS may differ markedly from those of patients treated privately. This issue requires further investigation, particularly in regard to the chronic nature of the problem and length of illness and comorbidity of patients treated privately versus those treated through NHS funding.

Patient Expectations From Complementary Therapy

Seven distinct but overlapping themes regarding patients’ expectations emerged from data analysis: relief of symptoms, desire for a therapeutic/holistic approach from treatment, wish to improve quality of life, provision of information by caregivers, reduction of the risk of allopathic treatments, need for self-help advice, and accessibility of such treatments on the NHS. These themes are presented in order of their frequency.

Relief of symptoms.

Symptom relief was the most dominant theme within the data. Patients, particularly sufferers of a chronic illness, commented on the need to cure their illness or to gain some relief from their symptoms. Some patients were very specific about the kinds of symptoms for which they were seeking relief, whereas others were more general. One 50-year-old woman reported, “I have a deep-seated problem in the small of my back which recurs occasionally. When it does, I am severely limited in my movement.” Patients also illustrated how their symptoms adversely affected their lives:

The skin problem manifested on my face upsets me very much, but doctors do not seem to appreciate this fact. I like to look my best and feel that I don’t. I am very embarrassed by this and hate anyone to see me without cover-up cream. I hope that my condition can be helped, especially the skin problem. No one seems to understand how awful I feel about it, but then it’s on my face, not theirs.

This patient also was expressing the importance of empathy and understanding from health care professionals who treat patients with such distressing problems.

Pain appeared to be a particularly prevalent problem. Patients were experiencing chronic pain and reported how distressing this was. It was also apparent that this pain caused physical limitations that affected quality of life; some patients were unable to perform simple daily activities. In some cases, the pain was constant: “I am constantly in severe pain through arthritis. I consult my own GP [and] all I get are pills, and it gets worse. . . .”

Several patients expressed a desire for increased mobility as well as the ability to continue to work. Patients reported how pain affected their daily lives and how it led to tiredness and depression. Rather than expecting definitive cures, some patients sought ways to control the pain. Others appeared to have multiple clinical problems of long duration; such problems seemed to exacerbate the pain or were a direct result of the pain. The chronic and long-term nature of health problems was evident in some comments; for example, “My chief problem is lack of confidence due to arthritis in the spine, spondylitis in neck, etc. I had a hip joint replacement 20 years ago. I use 2 sticks, walking frame, and holding on to furniture—extra rail on stairs.”

Holistic therapeutic approach.

Several patients expressed a desire for “an individual approach to be seen as a whole person.” This holistic approach was defined through the process of engagement that the patient expected to undergo with a practitioner. One 36-year-old woman said, “Most of all I would like to speak to someone and feel at ease with them and hope that they would be able to help me feel better as an individual and to feel happier in myself.” Another patient acknowledged the potential effects of a personal and therapeutic approach: “When you talk to someone on a one-to-one basis and they understand, you tend to feel more confident and comfortable, knowing that you’re not the only one that feels the way you do.” There was an expectation among patients generally that this holistic approach would address the cause of the problem as the individual was treated: “Yes, [there is] the knowledge that alternative therapies look to the cause of a problem and don’t just put a Band-Aid over the condition. If the cause can be found and treated, then the whole person can be healed.”

Quality of life.

This theme related to life limitations and possible improvements in health and well-being. Some patients mentioned the importance of health improvements that would enable them to get out and be more active:

As I have had ankylosing spondylitis for over 30 years and angina for about 7 years, I do not expect to be cured. But I hope that my back and pain from my frozen shoulder which I had for 4 months since my retirement at age 65 will be reduced enough to enable me to enjoy my gardening and an occasional round of golf.

Others expressed the desire for more energy to engage in social activities. One 41-year-old woman wrote:

I would like to feel less tired; although I am not in extreme pain, I feel very low in energy most of the time. I have to make a conscious effort a lot of the time to get energy. If I was not feeling so tired, I would be much happier. I often turn my family away to rest. Even people a lot older than myself seem to achieve more than myself in a day and be able to work a lot faster.

Provision of information by caregivers.

Some patients expected to be provided with information to gain a deeper understanding of their condition. They were particularly keen to be told the truth and expressed a need to be taken seriously: “To do the best [they can] and tell me the truth.” Patients perceived that such information provision might lead them to a better understanding of their condition and to a partnership with their health professional. One patient expressed a desire for “a satisfactory explanation of my condition, support, understanding, and real interest from the practitioner in my problem, so we can work together on the improvement of my health.”

Problems with allopathic medicine.

For some patients, allopathic treatment was not working.

I have been told by doctors that I could develop scoliosis, so I want to prevent that if possible. I suffer back/shoulder pain daily and especially in the lower back when I lie down for more than 6 hours or if I lie on my stomach. Traditional medicine has not been of any help. Most doctors say there is nothing wrong, that I could develop scoliosis and that there is nothing they can do to alleviate my pain—so I have turned to alternative therapy, which I find at least recognizes my problem.

Concerns about taking medications (particularly on a long-term basis) and about their potential side effects were highlighted as reasons to obtain complementary therapy. The limitations of conventional medicine were expressed in the context of seeking a different approach for the treatment of a long-term problem. One 38-year-old woman wrote, “I have had this illness—ulcerative colitis—for 20 years and have always been on drugs. My health is such that I can’t survive in a healthy way without drugs. Another alternative is surgery, which I feel is my last resort.”

Self-help and advice.

Patients recognized the chronic nature of their problems and wanted to find ways to cope with them; they also expected guidance on self-help mechanisms and advice to help them more fully understand the nature and cause of their problems so that they could cope with or do something about them. A common factor in the theme of self-help was the expectation that advice would be given on what patients themselves could do to reduce their symptoms’ impact: “To be advised and encouraged, and to be made aware of how I can improve and help myself. To reach a better state of health and also mind.”

Accessibility of treatment.

Patients were concerned about access to the NHS complementary therapy service and expressed this concern in a number of ways. Expectations were not strictly related to the treatment but also pertained to the service generally. Patients appeared to prefer to express issues about accessibility to the service organizers rather than to the researcher, even though the postage-paid envelope for the questionnaire was addressed to the research unit. The first issue patients expressed concern about related to access to service for the patients themselves and to their concern about the financial resources needed to seek this treatment privately. The second issue was a more general concern about the availability of complementary therapy: “I expect it to be provided on the NHS and [to be] more widely available.”

DISCUSSION

Little is known about the expectations of patients who seek complementary therapies. The findings of this study support the results of a previous, unpublished study in which patients were found to have hopes for a cure, symptom relief, information, and understanding.11 In this study, the impact of patients’ problems on their ability to live normal lives and carry out routine daily activities is evident. Patients’ comments indicate a failure of conventional medicine to alleviate some of their problems, an important finding for public health because it suggests an area of unmet health needs that some complementary therapies might support. For example, areas of limitation in conventional medicine could be scrutinized in the context of the strengths of complementary therapies, thereby providing an opportunity to integrate appropriate services.

Patients appeared to have high expectations of complementary therapy and to assume that such therapy was inherently linked to a holistic approach and a therapeutic relationship founded on trust and support. They expected to be treated as individuals rather than as a collection of symptoms. Understanding and empathy were features of their expectations, and patients believed that an understanding and empathetic approach might aid recovery. These expectations of patients raise a number of issues for health care practice and further research. Efficacy of complementary therapies is separate from but intertwined with how the therapies are delivered (e.g., with empathy and understanding).24 More in-depth research is required to substantiate why and how patients hold the assumption that complementary therapy is holistic.

To the extent that patients expect a cure, researchers need to examine the evidence for the effectiveness of therapies; however, to the extent that patients expect to be treated with empathy and understanding, it is appropriate to determine to what extent such expectations are being, or indeed can be, met by both complementary and conventional practitioners.

The themes that emerged from the data analysis were clearly important to individual patients. These themes provide a “flavor” of what patients expect and the diversity of their expectations. A quantitative representation of patient expectations could provide a basis for the development of a questionnaire that would be used to survey a larger group and that would require patients to rank items by importance. This study suggests that patients have high expectations of complementary therapies; however, the relationship between these expectations and therapeutic outcomes is uncharted territory that requires detailed exploration. Only through an understanding of patient expectations, together with evidence for the effectiveness of complementary therapies, can patients be supported in making appropriate and realistic treatment choices.

Acknowledgments

I thank Katie Yiannouzis of The Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery, King’s College, London, for data screening and validation.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was required for this study, as the data were collected via questionnaire.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Sharma U. Complementary Medicine Today: Practitioners and Patients. London, England: Tavistock/Routledge; 1992.

- 2.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher P, Ward A. Complementary medicine in Europe. BMJ. 1994;309:107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vickers A. Use of complementary therapies [letter]. BMJ. 1994;309:1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacLennan AH, Wilson DH, Taylor AW. Prevalence and cost of alternative medicine in Australia. Lancet. 1996;347:569–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wootton JC, Sparber A. Surveys of complementary and alternative medicine, III: use of alternative and complementary therapies for HIV/AIDS. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas KJ, Nicholl JP, Coleman P. Use and expenditure on complementary medicine in England: a population based survey. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst E, Willoughby M, Weihmayr T. Nine possible reasons for choosing complementary medicine. Perfusion. 1995;11:356–359. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent C, Furnham A. Why do patients turn to complementary medicine? An empirical study. Br J Clin Psychol. 1996;35:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furnham A, Kirkcaldy B. The health beliefs and behaviours of orthodox and complementary medicine clients. Br J Clin Psychol. 1996;35:49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell A, Cormack M. The Therapeutic Relationship in Complementary Health Care. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

- 12.Richardson J. Clinical implications of an intersubjective science. In: Velmans M, ed. Investigating Phenomenal Consciousness. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2000:167–192.

- 13.Fitzpatrick R, Boulton M. Qualitative methods for assessing health care. Qual Health Care. 1994;3:107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse JM, ed. Qualitative Nursing Research: A Contemporary Dialogue. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1989.

- 15.Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:42–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson J.Developing and evaluating complementary therapy services, I: establishing service provision through the use of evidence and consensus development. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson J. Developing and evaluating complementary therapy services, II: examining the effect of treatment on health status. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:315–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamberts H, Wood M, Hofmans-Okkes I, eds. The International Classification of Primary Care in the European Community. London, England: Oxford University Press; 1993.

- 19.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, eds. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London, England: Routledge; 1994.

- 20.Lincoln YS, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, Calif: Sage Publications; 1985.

- 21.Burnard P. A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today. 1991;11:461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas KJ, Carr J, Westlake L, Williams BT. Use of non-orthodox and conventional health care in Great Britain. BMJ. 1991;302:207–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fulder S. The Handbook of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1996.

- 24.Peters D, ed. The Placebo Response: Biology and Belief in Clinical Practice. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2001.