Abstract

Objectives. We examined associations between depressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality after controlling for antiretroviral therapy use, mental health treatment, medication adherence, substance abuse, clinical indicators, and demographic factors.

Methods. One thousand seven hundred sixteen HIV-seropositive women completed semiannual visits from 1994 through 2001 to clinics at 6 sites. Multivariate Cox and logistic regression analyses estimated time to AIDS-related death and depressive symptom severity.

Results. After we controlled for all other factors, AIDS-related deaths were more likely among women with chronic depressive symptoms, and symptoms were more severe among women in the terminal phase of their illness. Mental health service use was associated with reduced mortality.

Conclusions. Treatment for depression is a critically important component of comprehensive care for HIV-seropositive women, especially those with end-stage disease.

Previous research has confirmed associations between depression and immune suppression and other negative health outcomes, such as disability and mortality.1–3 Recently, attention has turned to the effects of depression on the health of individuals whose immune systems have been affected by HIV infection. Yet, the relationship between depression and HIV disease progression is not well understood. For example, Sambamoorthi et al.4 found relationships between depression and HIV infection status, declines in immune function, accelerated disease progression, increased disability, shorter survival, and greater probability of death. Conversely, studies by Lyketsos et al.5 and Vedhara et al.6 challenge the characterization of depression as an independent or even a significant determinant of HIV disease progression. An additional complicating factor has been suggested by a recent study that found use of protease inhibitors reduces both depressive and clinical symptoms.7

The existence of a potential association between women’s depression and HIV disease progression is of interest to both health care providers and patients for several reasons. First, women’s rate of depression is twice as high as that of men among the general population.8 Second, HIV-seropositive women who have high levels of depressive symptomatology are significantly less likely to use highly active antiretroviral therapies.9 Third, depression is associated with poor adherence to antiretroviral treatment regimens,10,11 which in turn is associated with poor disease outcomes, such as mortality.12 Finally, depression is a significant predictor of non–AIDS-related deaths (e.g., those caused by accident, drug overdose, violence, and non–AIDS-associated malignancies) among HIV-seropositive women.13

Only 1 previous study of a cohort of HIV-seropositive women—the longitudinal study of the 4-site HIV Epidemiologic Research Study (HERS)14—has confirmed a link between chronic depressive symptomatology and poor AIDS-related outcomes. Among a cohort of HIV-seropositive women who were followed from 1993 through 2000 (demographic and clinical factors were controlled), the women who had chronic depressive symptoms were twice as likely to die as the women who reported no depressive symptoms or only intermittent ones.

We attempted to replicate and expand the HERS cohort findings by using the same variable definitions and types of statistical analyses and by exploring the effects of 3 additional factors: adherence to highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) and other HIV-related therapies, use of mental health services, and occurrence of depressive symptoms during the terminal phase of AIDS-related illness. Three research questions were addressed. First, do depressive symptoms predict time to AIDS-related mortality among a cohort of HIV-seropositive women? Second, does use of mental health services lower the likelihood of AIDS-related mortality? Third, do women in the terminal phase of their AIDS-related illnesses show higher likelihood than surviving women of meeting criteria for depression at the 2 study visits preceding their deaths?

METHODS

Study Background

Between October 1994 and November 1995, 2059 HIV-seropositive women were enrolled in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) at 6 medical and university consortia sites nationwide: Brooklyn, NY; Bronx, NY; Chicago, Ill; Los Angeles, Calif; San Francisco, Calif; and Washington, DC. Over the next 7.5 years, participants completed WIHS study visits at 6-month intervals. Specific responses to items in the interview protocol prompted interviewers to offer respondents referrals to medical or psychosocial services, such as gynecologic care or substance abuse treatment.

Measures

Depressive symptoms.

We used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D),15 a 20-item Likert-scaled instrument, to assess depressive symptoms. The CES-D has excellent reliability, validity, and factor structure among numerous subgroups,15 and it is commonly used in studies of HIV populations, including women.7 Its sensitivity for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition16 (DSM-III), diagnosis of major depression is excellent, in the 80% to 90% range, with somewhat lower specificity (70%–80%).17,18 In an earlier analysis of the WIHS cohort’s level of depressive symptoms, Cook et al.9 demonstrated that various ways of analyzing the CES-D (the standard cutoff of 16, a more stringent cutoff of 23, and an interval-level version of the subscale that excluded somatic items similar to HIV symptoms) produced virtually identical associations with antiretroviral therapy use and with the woman’s demographic characteristics. Thus, the standard cutoff score of 16 was used in our study.

We used 2 measures of longitudinal depressive symptoms to test the study hypotheses. First, following Ickovics et al.,19 depression chronicity was defined as the proportion of study visits at which the women’s self-reported CES-D scores met or exceeded the clinical cutoff for probable cases of depression. In this operationalization, or way of computing a depressive symptom variable, scores that indicated depression at 75% or more of the study visits were classified as chronic, 26% to 74% were classified as intermittent, and no more than 25% were classified as none or few. Second, following Lyketsos et al.’s5 “conservative” definition, scores of 16 or higher on the CES-D at 2 consecutive study visits were used to define recent depression. In our study, this was operationalized as scoring above the cutoff (1) at the last 2 study visits preceding death among women with AIDS-related deaths, and (2) at the last 2 study visits completed for all surviving women. The first operationalization of depression chronicity was used to test hypotheses 1 and 2, and the second operationalization of recent depression was used to test hypothesis 3.

AIDS-related mortality.

Information was collected on all participants’ deaths, malignancies, tuberculosis, and AIDS. Cause of death was coded from death certificates and from information obtained electronically via the National Death Index, local death registries, hospital records, physician reports, and families or friends. Deaths were classified as caused by AIDS if the cause was an AIDS-defined opportunistic infection/malignancy (consistent with 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical surveillance conditions), or if the stated cause was organ failure or nonspecific infection and the CD4 count at the last study visit was less than 200 cells per milliliter. This methodology has been described elsewhere.13

Independent measures.

Women were considered to be on a HAART regimen if they followed the International AIDS Society–USA panel20 and the US Department of Health and Human Services/Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Panel21 guidelines. All other antiretroviral therapy combinations were defined as non-HAART combination therapy, and use of a single antiretroviral therapy was defined as monotherapy.

At each study visit, HIV antibody status, HIV-1 RNA, and CD4 T-lymphocyte count were determined with standard flow cytometry at laboratories participating in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assurance Program. Viral load was classified as less than 4000 versus greater than 4000. CD4 levels were assessed as low (< 200), moderate (200–500), and high (> 500).

Study participants’ race/ethnicity was categorized as African American, Hispanic/Latina, White, and other. Illicit drug use was categorized as use of crack, cocaine, or heroin at any time during the study. Those with high school degrees or any postsecondary education at baseline were coded as “1” and as “0” otherwise. Age at baseline was measured in decades. Employment status at baseline was defined as any paid work (full- or part-time). Presence of clinical symptoms at baseline included 1 or more HIV/AIDS-related symptoms: fever, diarrhea, memory problems, numbness, weight loss, confusion, and night sweats. Women who reported nonadherence to any HIV treatment at any study visit were classified as nonadherent and as adherent otherwise. This single-item operationalization is similar to one that was used successfully by Wilson et al.22 in a previous analysis of medication adherence among the WIHS cohort. Those women who reported no HIV-related therapies were included in the adherent classification, because nonadherence is a predictor of mortality distinct from treatment. Mental health service use was defined as receipt of care from a mental health professional or counselor that was self-reported at 1 or more study visits. Indicator variables represented 5 of the 6 study sites; Chicago served as a sixth arbitrary reference category.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed 13 waves of semiannual data from the HIV-seropositive sample of the WIHS to predict time to AIDS-related death. We used the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to test for differences in survival function according to depressive symptom chronicity, and we used proportional hazards analysis to examine the effect of depressive symptoms after we controlled for potentially confounding factors. Data from women whose deaths were caused by non–AIDS-related causes (n = 144) were retained in the analysis until the time of death, when they were right-censored. We used multiple logistic regression analysis to predict the likelihood of meeting “probable depression” criteria at the final 2 study visits for all women to examine the association between depressive symptoms and end-stage disease.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics.

Participants who had less than 3 study visits (n = 343) were excluded from the sample so depression chronicity could be assessed longitudinally. When compared with the women who were included in the analysis (n = 1716), those with less than 3 study visits were significantly less likely to be employed (13% vs 22%) or to have used a HAART regimen for 12 or more months (1% vs 49%). The 2 groups did not differ significantly on any other variables. The demographic characteristics of the study’s 1716 women at baseline closely resembled those of the larger HIV-seropositive WIHS cohort.23 Two fifths (41%) reported illicit drug use before baseline, and 39% did so during the study. Baseline CD4 counts were below 200 cells for 25% of the women, and viral loads were greater than 4000 for 68%. Use of a HAART regimen for 1 year or more was reported by 49% of the women, and 14% reported use of a non-HAART combination therapy for 1 year or more. Only 5% reported use of monotherapy for 1 year or more, and 32% reported no use of an antiretroviral therapy or use for less than 1 year.

At baseline, more than half (58%) the women reported HIV-related clinical symptoms. Less than half (45%) were classified as adherent at all study visits; 37% reported perfect adherence, and 8% reported no treatment. For the remaining 55%, the mean number of visits at which nonadherence was reported was 3.

Approximately one third of the women (32%) reported depressive symptoms at a level that exceeded the CES-D clinical cutoff at 75% or more of their study visits. Another third (37%) reported depressive symptoms intermittently, and the final third (31%) reported depressive symptoms at few or none of their study visits. Close to half the women (47%) exceeded the CES-D clinical cutoff at their last study visit, and one third (35%) did so at their last 2 consecutive visits, which indicated recent depression among one half to one third of the cohort. Over two thirds (69%) reported use of mental health services at 1 or more study visits.

Relationship between depressive symptoms and time to death.

Two hundred ninety-four (17%) of the women died during the 13 waves of study visits completed over a 7.5-year period by 1716 women: 147 (9%) died from AIDS-related causes, and an additional 147 women (9%) died as a result of other causes (accidents, violent crime, suicide, or non–HIV-related diseases). Of those who died from AIDS-related causes, 66% had CES-D scores greater than or equal to 16 at their last study visit (the mean number of days between death and last visit was 146), and 52% had CES-D scores that exceeded the cutoff at their last 2 visits before death.

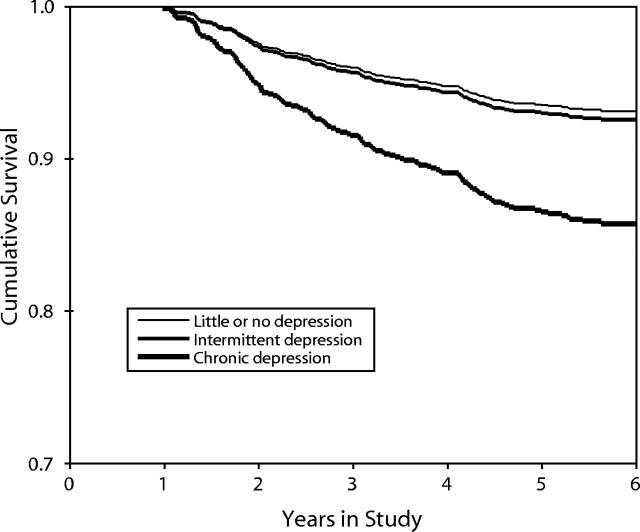

Figure 1 ▶ shows the Kaplan–Meier survival curves for mortality caused by AIDS for each of the 3 groups of women: those with chronic depressive symptoms, those with intermittent symptoms, and those with infrequent or no symptoms. These curves differ significantly (log-rank test = 20.22, df = 2, P < .001), which indicates that chronic depression predicts mortality. Whereas only 6% of the women who had few or no depressive symptoms, and only 7% of the women who had intermittent symptoms, died from AIDS-related causes, nearly double this proportion (13%) of the women who had chronic depressive symptoms did die from AIDS-related causes. We eliminated the somatic symptoms from the depression measure but retained a cutoff of 16 to test a more stringent measure of chronic depressive symptoms, which produced virtually identical results (log-rank test = 12.94, df = 2, P < .01).

FIGURE 1—

Kaplan–Meier survival curves, stratified by level of depressive symptoms.

Relationships among mortality and depressive symptoms and baseline features.

The third column of Table 1 ▶ shows bivariate odds ratios for AIDS-related mortality and other potential predictors. Women who had chronic depressive symptoms were more than twice as likely to die compared with those who had limited or no symptoms. AIDS-related mortality also was more likely among those who received monotherapy and those who had low baseline CD4 cell counts, high viral loads, and HIV-related symptoms at baseline. Mortality was less likely among those who reported mental health service use and those who were on a HAART regimen or a non-HAART combination therapy. Mortality also was associated with adherence, which was a counterintuitive finding most likely caused by the fact that women who had more advanced disease were more likely to have initiated therapy. None of the other model variables was associated with AIDS-related mortality.

TABLE 1—

Bivariate and Multivariate Associations Among AIDS-Related Mortality, Depressive Symptoms, and Confounding Factors Among HIV-Positive Women (N = 1716)

| Variable | AIDS-Related Deaths, No. (%) | Bivariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Multivariate Relative Riska (95% CI) |

| Level of depression | |||

| Limited/no symptoms (n = 543) | 35 (6) | Reference | |

| Intermittent symptoms (n = 629) | 43 (7) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) |

| Chronic symptoms (n = 534) | 68 (13) | 2.2 (1.4, 3.3) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.7) |

| Mental health service utilization | |||

| Used services during study (n = 1187) | 82 (7) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) |

| No service use (n = 529) | 65 (12) | Reference | |

| Baseline CD4 cell count | |||

| < 200 (n = 409) | 104 (25) | 27.9 (11.4, 68.6) | 36.0 (13.9, 93.8) |

| 200–500 (n = 785) | 33 (4) | 4.0 (1.6, 10.2) | 4.7 (1.8, 12.3) |

| > 500 (n = 468) | 5 (1) | Reference | |

| Baseline viral load | |||

| ≤ 4000 (n = 536) | 5 (1) | Reference | |

| > 4000 (n = 1166) | 142 (12) | 13.8 (5.6, 33.6) | 6.8 (2.7, 16.9) |

| Baseline HIV symptoms | |||

| 0 (n = 714) | 42 (6) | Reference | |

| ≥ 1 (n = 999) | 105 (11) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.7) | 1.3 (0.8, 1.9) |

| Categorized antiretroviral therapy use during study | |||

| Other (n = 554) | 81 (15) | Reference | |

| Monotherapy ≥ 12 mos (n = 93) | 27 (29) | 2.4 (1.6, 3.7) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) |

| Non-HAART combination antiretroviral therapy ≥ 12 mos (n = 231) | 17 (7) | 0.4 (0.3, 0.7) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) |

| HAART ≥ 12 mos (n = 838) | 22 (3) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.2) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) |

| Adherence to HIV treatment regimen | |||

| Adherence reported at every visit (n = 775) | 82 (11) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.1) |

| Nonadherence at ≥ 1 visit (n = 938) | 65 (7) | Reference | |

| Crack, cocaine, heroin use during study | |||

| Any use (n = 663) | 63 (10) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) |

| No use (n = 1053) | 84 (8) | Reference | |

| Baseline age, y | |||

| < 30 (n = 331) | 27 (8) | Reference | |

| 30–39 (n = 829) | 67 (8) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) |

| 40–49 (n = 469) | 44 (9) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.9) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) |

| 50–59 (n = 75) | 8 (11) | 1.5 (0.7, 3.2) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.9) |

| ≥ 60 (n = 12) | 1 (8) | 1.1 (0.1, 8.0) | 0.7 (0.1, 5.7) |

| Employment status | |||

| Not employed (n = 1334) | 127 (10) | Reference | |

| Employed (n = 381) | 20 (5) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) |

| Education | |||

| At least high school or equivalent (n = 1080) | 87 (8) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.2) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.6) |

| Less than high school (n = 636) | 60 (9) | Reference | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/living as married (n = 628) | 57 (9) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.9) |

| Single (n = 1088) | 90 (8) | Reference | |

| Residential status | |||

| Living in own home (n = 1193) | 104 (9) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.6) |

| Living elsewhere (n = 522) | 43 (8) | Reference | |

| Income status | |||

| < $12 000/year (n = 1103) | 100 (9) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.5) |

| ≥ $12 000/year (n = 613) | 47 (8) | Reference | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| African American (n = 962) | 97 (10) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.4) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) |

| Hispanic/Latina (n = 405) | 27 (7) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.4) |

| Other (n = 384) | 23 (7) | Reference | |

Note. N = respondents with 3 or more study visits; CI = confidence interval; HAART = highly active antiretroviral therapy.

aRisk estimate was calculated from the Cox proportional hazards model, which associated each variable with mortality while the effects of all other variables in the table and the study site were controlled.

We used a Cox proportional hazards model to estimate the effect of depressive symptom chronicity on mortality after we controlled for all other model variables. As shown in the last column of Table 1 ▶, the women who had chronic depressive symptoms were significantly more likely to die compared with the women who had intermittent or fewer symptoms. The remaining results mirror those of the bivariate analysis, except that the positive association between mortality and adherence became nonsignificant (because of its spurious nature), as did relationships between mortality and HIV symptoms and mortality and monotherapy. Several potential interactions between model variables were tested and were found to be nonsignificant: an interaction between depression and mental health service use and interactions between adherence and use of different categories of HIV therapies.

Finally, because of the time frame of our study, it is possible that these results are biased by the fact that HAART became available only to those who survived for longer periods of time. To control for this potential bias, we restricted the sample to those women who were alive during the second half of 1996 (because protease inhibitors became commercially available at the beginning of 1996) and repeated the Cox regression analysis. The results (data not shown) were virtually identical to those in Table 1 ▶.

Relationships among depressive symptoms immediately preceding death, mortality, and confounding variables.

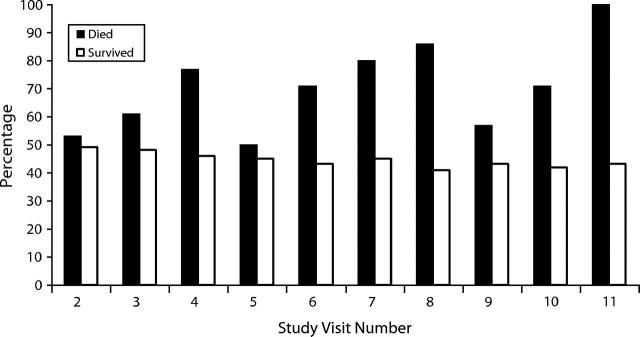

While depressive symptom chronicity is associated with mortality owing to AIDS-related causes, the chronicity measure fails to capture the level of depressive symptoms immediately before death. For example, the chronicity score of a woman who exceeded the CES-D clinical cutoff at the first 2 study visits but not the last 2 visits would be identical to that of a woman who exceeded the cutoff at the last 2 study visits but not the first 2. To examine the effect of depressive symptoms during the immediate premortality period, we computed the proportions of women who met criteria for probable depression at each study visit separately for those who died from AIDS-related causes during the subsequent 6 months versus those who survived until the next study visit. The results (Figure 2 ▶) indicated that the proportion of women who had probable depression was higher among those who died during the following 6 months than among those who survived.

FIGURE 2—

Percentage of HIV-positive women who met criteria for probable depression, by subsequent 6-month survival status.

Next, we used logistic regression analysis to examine the multivariate statistical association between depressive symptoms and being in the terminal phase of AIDS-related illnesses. Level of depressive symptoms was the dependent measure, and we used Lyketsos et al.’s5 “conservative” definition of meeting the CES-D cutoff at 2 consecutive study visits. These were the last 2 study visits completed by all women, excluding those who died from non–AIDS-related causes (n = 144).

As shown in the middle column of Table 2 ▶, the women who were in the terminal phase of their AIDS-related illnesses were more than twice as likely to report recent clinically significant depressive symptoms. More than half (52%) of the terminally ill women, but less than one third (32%) of the nonterminally ill women, met the “conservative” criteria for depressive symptoms. Clinically significant depressive symptoms also were more likely among those women who used mental health services, who had CD4 counts below 200 cells and viral loads above 4000, who had HIV-related symptoms at baseline, who reported illicit drug use, who were aged 30 to 49 years, who received monotherapy, who had incomes below $12 000 per year, and who were Hispanic/Latina. Depressive symptoms were less likely among women who were on a HAART regimen, who were adherent, who were employed, who had a high school or equivalent education, and who lived in their own homes.

TABLE 2—

Bivariate and Multivariate Associations Among Depressive Symptoms, AIDS-Related Mortality, and Confounding Factors Among HIV-Positive Women (N = 1569)

| Variable | Met Criteria for Clinical Depression, No. (%) | Bivariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Multivariate Odds Ratioa (95% CI) |

| Stage of illness | |||

| Teminal (n = 147) | 76 (52) | 2.3 (1.6, 3.3) | 1.8 (1.1, 2.7) |

| Not terminal (n = 1422) | 451 (32) | Reference | |

| Mental health service utilization | |||

| Used services during study (n = 1085) | 418 (39) | 2.2 (1.7, 2.8) | 2.2 (1.6, 2.9) |

| No service use (n = 484) | 109 (23) | Reference | |

| Baseline CD4 cell count | |||

| < 200 (n = 361) | 142 (40) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.9) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) |

| 200–500 (n = 720) | 232 (32) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) |

| > 500 (n = 439) | 136 (31) | Reference | |

| Baseline viral load | |||

| ≤ 4000 (n = 502) | 143 (28) | Reference | |

| > 4000 (n = 1046) | 374 (36) | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) |

| Baseline HIV symptoms | |||

| 0 (n = 666) | 132 (20) | Reference | |

| ≥1 (n = 900) | 395 (44) | 3.3 (2.6, 4.0) | 2.4 (1.8, 3.0) |

| Categorized antiretroviral therapy use during study | |||

| Other (n = 490) | 186 (38) | Reference | |

| Monotherapy ≥ 12 mos (n = 77) | 41 (53) | 1.8 (1.1, 3.0) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.2) |

| Non-HAART combination antiretroviral therapy ≥ 12 mos (n = 203) | 66 (33) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) |

| HAART ≥ 12 mos (n = 799) | 234 (29) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.8) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) |

| Adherence to HIV treatment regimen | |||

| Adherence reported at every visit (n = 684) | 207 (30) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) |

| Nonadherence at ≥ 1 visit (n = 882) | 320 (37) | Reference | |

| Crack, cocaine, heroin use during study | |||

| Any use (n = 599) | 248 (42) | 1.8 (1.4, 2.2) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) |

| No use (n = 970) | 279 (29) | Reference | |

| Baseline age, y | |||

| < 30 (n = 318) | 78 (24) | Reference | |

| 30–39 (n = 769) | 274 (36) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.3) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) |

| 40–49 (n = 405) | 154 (38) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.6) | 1.4 (1.0, 2.1) |

| 50–59 (n = 59) | 21 (36) | 1.7 (0.9, 3.1) | 1.5 (0.8, 2.8) |

| ≥ 60 (n = 9) | 0 (0) | 0.2 (0.0, 115.6) | 0.1 (0.0, 2942.0) |

| Employment status | |||

| Not employed (n = 1201) | 454 (38) | Reference | |

| Employed (n = 367) | 73 (20) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.6) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) |

| Education | |||

| At least high school or equivalent (n = 1000) | 300 (30) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.8) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) |

| Less than high school (n = 569) | 227 (40) | Reference | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/living as married (n = 587) | 186 (32) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.2) |

| Single (n = 982) | 341 (35) | Reference | |

| Residential status | |||

| Living in own home (n = 1096) | 344 (32) | 0.7 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) |

| Living elsewhere (n = 473) | 183 (39) | Reference | |

| Income status | |||

| < $12 000/year (n = 996) | 386 (39) | 2.0 (1.5, 2.4) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.8) |

| ≥ $12 000/year (n = 573) | 141 (25) | Reference | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| African American (n = 865) | 295 (34) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.8) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) |

| Hispanic/Latina (n = 381) | 143 (38) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.2) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) |

| Other (n = 323) | 89 (28) | Reference | |

Note. N = respondents with 3 or more study visits; CI = confidence interval; HAART = highly active antiretroviral therapy.

aOdds estimates were calculated from the logistic regression model, which associated each variable with depression while the effects of all other variables in the table and the study site were controlled.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis that controlled for all other factors found that recent clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms were associated with being in the terminal stage of illness, using mental health services, having HIV-related symptoms, and being aged 30 to 39 years. Recent depressive symptoms were significantly less likely among those who had been on a HAART regimen for 12 or more months.

DISCUSSION

Chronic depressive symptoms were significantly associated with a greater likelihood of AIDS-related mortality, even after we controlled for clinical, substance use, and sociodemographic factors. However, despite the impact of depressive symptoms, women who received mental health services were significantly less likely to die from AIDS-related causes during the study period. These results point to the importance of identifying and treating depression—through both pharmacological interventions and psychotherapeutic treatment—as an essential element in the comprehensive clinical care of women who have HIV.

Additionally, not only chronicity but also recency of depressive symptoms was associated with AIDS-related mortality. Of those in the terminal phase of their illnesses, more than half met CES-D–defined clinical criteria for depression at the 2 study visits before their deaths. The high proportion of women who reported depressive symptoms during the terminal phase of their AIDS-related illnesses shows the importance of including treatment for depression in end-of-life care protocols through the use of antidepressants and other treatments in hospice and similar programs.

Antiretroviral therapies clearly affected mortality: those who were on a HAART regimen for a year or more were 90% less likely to experience AIDS-related mortality, and those who were on a combination antiretroviral therapy for a year or more were 70% less likely. Moreover, in our study, the proportion of women who reported recent depressive symptoms was lowest among those who were on a HAART regimen. The significantly lower proportion of women who had depressive symptoms among users of the most potent antiretroviral therapies shows the possible role of a HAART regimen in combating depression7,24 along with or in addition to the role of positive mental health in promoting use of a HAART regimen. Also important are associations between depression and AIDS-related mortality in the context of unique factors related to women’s use of HAART regimens, such as health insurance status,25 which could potentially influence their access to both HIV and depression treatments.

Our study’s methodology did not allow us to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between depression and mortality, because both may be related to disease progression. However, the multivariate survival analysis controlled for 2 potent clinical indicators of HIV disease status (HIV viral load and CD4 cell count), and the significant relationship between mortality and depressive symptoms remained consistent despite these controls. Furthermore, post hoc analyses (data not shown) of women who did not have AIDS at baseline (i.e., CD4 > 200) revealed that those who had chronic depressive symptoms were 2.3 times more likely to die than those who had limited or no depressive symptoms (P < .05), which indicated that chronic depression was related to mortality even among those who did not have AIDS at baseline. Finally, women who died of AIDS-related causes were significantly more likely to have had CES-D scores that indicated “probable depression” at the 2 study visits immediately preceding their deaths, which established the temporally proximal, if not causal, nature of depression and mortality.

Two caveats to our findings concern the use of the CES-D to measure depressive symptoms and the use of death certificates to determine cause of death. With regard to the first study limitation, operationalization of major depression through research-quality diagnostic tools, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM or the Composite International Diagnostic Inventory, would have yielded a much higher-quality measure of depression as a syndrome, as would diagnostic procedures performed by a clinician who uses the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).26 All of these approaches are highly preferable to use of a depression screening instrument, such as the CES-D, because of the latter’s limited specificity. However, the measure is both valid and reliable and is widely used in studies of HIV-positive cohorts, which enables direct comparisons with the results of previous studies. Moreover, the use of rigorous scientific or clinical diagnostic tools among a population of this size presents considerable logistical challenges and requires substantial interrater and intersite reliability procedures to warrant its expense and its increased subject burden. Our study also was limited by our inability to determine whether the mental health services received by the women were consistent with practice guidelines for the treatment of depression that are based on rigorous research findings.

With regard to the second caveat, the causes of death obtained from death certificates may have been inaccurate. However, once again, death certificate information is commonly used in studies of this type and can provide important epidemiological information that otherwise might not be available. Additionally, the algorithm used in our study enhanced the linkage of AIDS clinical indicators (CD4 cell counts, viral load) to cause of death, which may have accounted for the substantial proportion of deaths classified as non–AIDS-related and most likely reduced chances of false-positive results.13

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of our study highlight a number of important and clinically meaningful associations between depressive symptoms and outcomes of women who have HIV. They suggest that antiretroviral therapy alone does not meet best-practice standards of care for this population, and therapy must be augmented by appropriate and sensitive mental health treatment, particularly as HIV disease progresses. Thus, finding ways to reduce depressive symptoms has the potential not only to prolong life but also to enhance its quality among women who have HIV.

Acknowledgments

The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with supplemental funding from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Craniofacial and Dental Research (U01-AI-35004, U01-AI-31834, U01-AI-34994, U01-AI-34989, U01-HD-32632, U01-AI-34993, U01-AI-42590, M01-RR00079 and M01-RR00083).

Data were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (principal investigators are listed in parentheses) at the New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); the Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); the Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); the Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); the Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); and the Data Coordinating Center (Alvaro Munoz).

Human Participant Protection The Women’s Interagency HIV Study has been approved by the institutional review boards of all institutions involved in our study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Contributors J. A. Cook, D. Grey, and J. Burke designed the study, analyzed the data, and prepared the article. M. H. Cohen, A. C. Gurtman, J. L. Richardson, T. E. Wilson, M. A. Young and N. A. Hessol contributed to the data interpretation and the writing of the article. All authors reviewed drafts of the article and contributed revisions.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Reichlin S. Mechanisms of disease: neuroendocrine-immune interactions. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1246–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbert TB, Cohen S. Depression and immunity: a meta-analytical review. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:472–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rovner BW, German PS, Brant LJ, Clark R, Burton L, Folstein MF. Depression and mortality in nursing homes. JAMA. 1991;265:993–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sambamoorthi U, Walkup J, Olfson M, Crystal S. Antidepressant treatment and health services utilization among HIV-infected Medicaid patients diagnosed with depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:311–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyketsos CG, Hoover DR, Guccione M, et al. Depressive symptoms as predictors of medical outcomes in HIV infection. JAMA. 1993;270:2563–2567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vedhara K, Giovanni S, McDermott M. Disease progression in HIV-positive women with moderate to severe immunosuppression: the role of depression. Behav Med. 1999;25:43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low-Beer S, Chan K, Yip B, et al. Depressive symptoms decline among persons on HIV protease inhibitors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey: I. Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affective Disord. 1993;29:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook JA, Cohen MH, Burke J, et al. Effects of depressive symptoms and mental health quality of life on use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordillo V, del Amo J, Soriano V, Gonzalez-Lahoz J. Sociodemographic and psychological variables influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13:1763–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleeberger CA, Phair JP, Strathdee SA, Detels R, Kingsley L, Jacobson LP. Determinants of heterogenous adherence to HIV-antiretroviral therapies in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection [published erratum appears in Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:253]. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen MH, French AL, Benning L, et al. Causes of death among women with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Am J Med. 2002;113:91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, et al. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV epidemiology research study. JAMA. 2001;285:1466–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

- 17.Breslau N. Depressive symptoms, major depression, and generalized anxiety: a comparison of self-reports on CES-D and results from diagnostic interviews. Psychiatry Res. 1985;15:219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman M, Coryell W. Screening for major depressive disorder in the community: a comparison of measures. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ickovics JR, Thayaparan B, Ethier K. Women and AIDS: a contextual analysis. In: Baum A, Revenson T, Singer J, eds. Handbook of Health Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000:821–839.

- 20.Carpenter CC, Cooper DA, Fischl MA, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in adults: updated recommendations of the International AIDS Society–USA Panel. JAMA. 2000;283(3):381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Dept of Health and Human Services/Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Panel on Clinical Practices for the Treatment of HIV Infection. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents [monograph online] 2002 Feb. Available at: http://hivatis.org. Accessed March 6, 2002.

- 22.Wilson TE, Barron Y, Cohen M, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its association with sexual behavior in a national sample of women with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Judd FK, Cockram AM, Komiti A, Mijch AM, Hoy J, Bell R. Depressive symptoms reduced in individuals with HIV/AIDS treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy: a longitudinal study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:1015–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook JA, Cohen MH, Grey DD, et al. Use of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a cohort of HIV-seropositive women. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:82–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.