Abstract

The maternal mortality rate in Sweden in the early 20th century was one third that in the United States. This rate was recognized by American visitors as an achievement of Swedish maternity care, in which highly competent midwives attend home deliveries. The 19th century decline in maternal mortality was largely caused by improvements in obstetric care, but was also helped along by the national health strategy of giving midwives and doctors complementary roles in maternity care, as well as equal involvement in setting public health policy.

The 20th century decline in maternal mortality, seen in all Western countries, was made possible by the emergence of modern medicine. However, the contribution of the mobilization of human resources should not be underestimated, nor should key developments in public health policy.

THE DECLINE OF MATERNAL mortality in Western countries after the 1930s is believed to be associated mainly with the emergence of modern obstetric care, while it has been proposed that public health policy, poverty, and the malnutrition associated with poverty were of relatively minor importance.1 But the maternal mortality pattern before the emergence of modern medical technology was not uniform in all Western countries. In The Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden, low maternal mortality rates were reported by the early 20th century and were believed to be a result of an extensive collaboration between physicians and highly competent, locally available midwives.2 From 1900 through 1904, Sweden had an annual maternal mortality of 230 per 100 000 live births, while the rate for England and Wales was 440 per 100 000. For the year 1900, the United States reported 520 to 850 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births.3 This very high maternal mortality rate, especially if compared with the lower rates achieved in several less prosperous European countries, caused some American obstetricians to express concern.

Joseph B. DeLee, commemorated as a titan of 20th-century obstetrics, studied maternity services in Europe before he established the Chicago Lying-In Hospital and Dispensary in 1895. His aim was to provide delivery assistance to poor women by also offering them the option of having a safe and inexpensive home delivery.4

George W. Kosmak5 visited Scandinavia in 1926 and was reported to have been very impressed with the medical systems in place there. In an address to the American Medical Association, Kosmak talked about the good results obtained in a carefully supervised system of midwife instruction and practice. He stated,

To begin with, the midwife in Scandinavia is not regarded as pariah. . . . One sees, therefore, in the training schools for midwives, bright, healthy looking, intelligent young women of the type from whom our best class of trained nurses would be recruited in this country, who are proud of being associated with an important community work, and whose profession is recognized by medical men as an important factor in the art of obstetrics, with which they have no quarrel.

He concluded, “The results of this midwife training are evidently excellent because the mortality rates of these countries are remarkably low and likewise, the morbidity following childbirth.”5

What, then, was the history of this system that turned out to be a good example for the United States before the emergence of modern medicine in the 1930s? The aim of this review is to depict the Swedish intervention against maternal mortality in the 18th and 19th centuries and the decline in maternal mortality in the Western countries in the 20th century.

HISTORICAL SETTING: SWEDEN

The history of maternity care in Sweden should be interpreted in light of the involvement of the state in public health. One important part of the emergence of the Swedish national state in the 16th century was the creation of the Lutheran State Church. In the 17th century, the Swedish clergy created an information system that included all individuals in their parishes older than 6 to 7 years. By the middle of the 18th century, this registration included the entire population. The information system was based on the annual catechetical examination of every household, where the clergy examined knowledge of the catechism as well as the reading ability of all household members. To this “church book,” other types of records were linked: records of in- and outmigrations, births and baptisms, bans and marriages, and deaths and burials. The Office of the Registrar General (Tabellverkskommissionen), founded in 1749, compiled national statistics from the ecclesiastical registry. National vital statistics were therefore available in Sweden before they were available in any other European country.

The profession of physician was legalized in 1663 with the foundation of the Collegium Medicum. In the 17th and 18th centuries, many Swedish academics obtained their postdoctoral training from universities in Germany, France, Italy, England, and The Netherlands. By the beginning of the 18th century, Sweden had declined as a major power in northern Europe. Inside Sweden, the power of the Swedish parliament was enhanced; a so-called “Time of Freedom” was introduced that coincided with the Age of Enlightenment. There began an era of scientific blossoming. The two professors of medicine at Uppsala University, Carl von Linné (1707–1778) and Nils Rosén von Rosenstein (1706–1773), and the head of the Collegium Medicum, Abraham Bäck (1713–1795), were the initiators and promoters of health care and public health within the Commission of Health (Sundhetskommissionen) from 1737 to 1766. They presented programs for primary health care and preventive measures for communicable diseases and published pamphlets on health education, nutrition, and hygiene. From the start, the public health program had an equity perspective by reaching out to the poor rural population and making health care accessible to them. The policy fit in with the prevailing political ideology of the time, mercantilism, which defined the wealth of the nation by the number of its citizens.6 The military need of the nation has also been proposed as an argument for investment in mothers’ and children’s health.7

The first national statistics on maternal mortality were presented in 1751, revealing a rate of almost 900 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births. In the same year, the Commission of Health stated, “Out of 651 women dying in childbirth, at least 400 could have been saved if only there had been enough midwives.” This became the starting point for the Swedish authorities to campaign for improvements in obstetric care, mainly by improving training for physicians and midwives and implementing a system of surveillance of midwives, both at the county and national level. What they did not know at the time was that it would take 150 years to achieve their goal.6

LICENSED MIDWIVES

The professionalization of birth assistance in Sweden began in the early 18th century. Pioneering this was Johan von Hoorn (1662–1724), who trained in obstetrics at the Hotel Dieu Hospital in Paris before returning to Sweden. In 1697, von Hoorn published a textbook titled The Well-Trained Swedish Midwife (Den Swenska wäl-öfwade JordGumman) intended for use by both midwives and the public. In 1711, the Collegium Medicum announced a decree of authorization for midwives that required a 2-year training period with an experienced midwife, followed by an examination given by the Collegium Medicum. In 1715, von Hoorn published a textbook for midwifery training with Soranus, the famous Roman gynecologist (50–129 AD), as a source of inspiration; in it, he stressed the importance of surveillance of the delivery by internal examination—that is, the noninterventionist approach emphasizing patience and waiting. He also described the mouth-to-mouth resuscitation method for reviving an apparently dead newborn. Soon the need for licensed midwives became apparent and the Collegium Medicum urged Sweden’s parliament to push for a national midwifery school. However, it was not until the end of the century that such a school was started.

In 1757, the Collegium Medicum’s proposal for a national training program for midwives covering all parishes was finally approved. Each parish was expected to pay for its students’ allowance in Stockholm. The first professor in obstetrics was appointed in 1761, and the first lying-in hospital, Allmänna Barnbördshuset in Stockholm, was founded in 1775.

The founding of Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute in 1810 led to a further improvement of obstetric care at a national level. A new government decree stated in 1819 that every parish was required to employ a licensed midwife, and that the parishes were also responsible for variola (smallpox) vaccinations. The midwife’s formal education was extended to 6 months, and the government paid allowances for 12 students each year. This meant that instead of limiting the training program to the women sent by the parishes, the profession was opened up to all interested women.

The professor of obstetrics at the time, Pehr Gustaf Cederschiöld (1782–1848), pushed hard to increase the competence of midwives. By 1829, health reform brought new regulations authorizing midwives, after an extended training period, to use forceps, sharp hooks, and perforators, in addition to their ability to perform manual removal of the placenta and extraction in breech presentation. This reform was opposed by contemporary international medical societies7 but was motivated by the long tradition of community midwives who assisted at home deliveries. The widely scattered rural Swedish population made it a necessity for midwives to be capable of acting in emergencies when physicians could not be reached. Cederschiöld argued that the reform would strengthen the authority and acceptance of the midwife in the parishes.8 Cederschiöld then wrote the textbooks Manual for Midwives (Handbok för Barnmorskor) and Guide to Instrumental Obstetrics (Utkast till Handbok i den Instrumentala Förlossningskonsten) in support of his ambition to increase the competence of midwives.

By the government decree of 1819, midwives were required to ensure that every newborn child had his or her own bed to prevent suffocation, although little observance of this rule was reported.9 In the mid-19th century, the authorities added more regulations for midwives. It was decided that their duties should not be limited only to childbirth, but should also include subsequent care of the infant. Consequently, education in basic neonatal care at the midwifery school was improved, with an emphasis on warmth, neonatal resuscitation with tactile stimuli for asphyctic children, daily care of the umbilicus, and early breastfeeding. Many mothers fed their newborns cows’ milk, and doctors and midwives began informing young mothers and mothers-to-be about the benefits of breastfeeding. This strategy soon had the desired effect, and infant mortality was reduced by 20%.10

The antiseptic technique was introduced in the lying-in hospitals during the late 1870s and, by law, to midwives in rural districts in 1881. Also, the Credé prophylaxis to prevent neonatal blennorrhea became one of the midwife’s duties.

COMPLEMENTARY ROLES OF MIDWIVES AND DOCTORS

The professionalization of birth attendance was not a smooth process. Historian Christina Romlid describes the antagonism, struggles, and conflicts that arose between the medical profession and traditional birth attendants until the late 19th century.8 In the Swedish parliament, the peasantry protested against the midwife regulation of 1777. This rule contained a “quackery paragraph” that banned traditional birth attendants, whom the peasants viewed as experienced and skilled, not as dangerous and harmful as stated in the regulation. Subsequently, the Crown withdrew the paragraph and reinstated the right of district medical officers and licensed midwives to train women locally. The paragraph was reinstated in 1819 in a milder form, allowing traditional birth attendants when a licensed midwife could not attend or arrive in time. However, during the 19th century, several traditional birth attendants were prosecuted and found guilty of unauthorized help during childbirth.8 Not until the late 19th century did professional midwifery become fully established and legitimized in the rural areas of Sweden.

Whereas during the 18th century midwives were recruited from among farming families, by the 19th century the profession of midwife had become a legitimate occupation for women from all walks of life, and it carried as much weight and respect as that of primary school teacher.11 Consequently, the community midwife became a central figure and was often the only person representing health care at the parish level. Over time, any technical constraints were overcome and there was good social representation among midwives, thus ensuring a successful implementation of obstetric services within the specific cultural context of rural Sweden.

The professionalization of birth assistance can be interpreted from a gender theory perspective as a successive subordination of women consequent to the appearance of male obstetricians. Birthing is a natural event, yet female traditional birth attendants were pushed aside with the medicalization of childbirth. The American and British experience of conflicts between doctors and midwives is a recurrent theme, and Swedish historians have reported parallels in Sweden, although more in Stockholm than in the rural areas.8,12 However, studies addressing the professionalization of Swedish midwives in relation to the theories of sociology, modernity, gender, and the evolution toward scientifically based obstetric care have found few conflicts between doctors and midwives.11 There was a gender division in the professionalization process; however, since doctors and midwives were disseminators of the same discourse and worked toward the same goal, they complemented rather than competed against each other, unlike in the US urban setting.11

These complementary roles were facilitated by the conditions of health care in Sweden. As recently as the late 19th century, only 10% of the Swedish population lived in urban areas. Obstetricians were in office only in the lying-in hospitals of Stockholm and, from 1865, also in Gothenburg and Lund. Otherwise, general practitioners in the counties and towns were the medical counterparts of the midwives assisting at home deliveries. In practice, no system of referral was available in the 19th century. In medical emergencies, the midwife called for the doctor, but this rarely happened. This setting facilitated a more noninterventionist attitude, manifesting fairly low rates of assisted delivery throughout Swedish history and strengthening the midwife in her role as the indisputable birth attendant, in contrast to the more doctor-oriented obstetrics emerging in the United States by the 20th century.11

The Swedish model of maternity services was distinct even from the European perspective. In 1870, the ratio was 3.1 midwives for every doctor for Sweden, while it was 1.4 in Denmark and Norway7 and 1.2 in France.13

Community midwifery was based on a system of very close supervision and retraining. In each county, each midwife was required to report to the county general practitioner. Her report had to be detailed and include the actual record, in diary form, of all deliveries she had attended, with information on the identity of the parturient, complications, the sex of the child, birthweight, and outcome for the mother and child. Also, review courses for midwives were obligatory on a regular basis. A standardized protocol was necessary when midwives used forceps, sharp hooks, or perforators, giving the reasons for the intervention and the outcome. This protocol had to be signed by the county physician and was registered at the National Health Bureau.

MATERNAL MORTALITY IN THE 17TH TO 19TH CENTURIES

In the 17th century, maternal deaths accounted for 10% of all female deaths between the ages of 15 and 49 years.14 In women aged between 20 and 34 years, 40% to 45% of deaths among married women were caused by complications of pregnancy or delivery. Among married women, 1 of 14 died during childbirth.15

Maternal mortality declined from 900 per 100 000 live births to 230 per 100 000 from 1751 to 1900. The general trend toward a decline was interrupted during the years 1850 to 1880, when the recorded septic maternal mortality coincided with an increase in total mortality due to communicable diseases. During the 19th century, areas of high maternal mortality were not restricted to the urban environments, where there was a known high death rate due to puerperal sepsis.14

During the 19th century, the decline in maternal mortality was far greater than that in infant mortality, or in mortality due to tuberculosis. The decline in maternal mortality was especially pronounced between 1861 and 1900, when the percent reduction dropped from 59% to 24%, while the female mortality reduction leveled out.16

In the 19th century, two thirds of maternal deaths had direct obstetrical causes, such as difficult labor, eclampsia, hemorrhage, and sepsis, while one third were indirect obstetric deaths due to diseases such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, dysentery, heart disease, and malnutrition.15,17 In the lying-in hospitals, before antiseptic techniques became known most maternal deaths were caused by puerperal sepsis.18 However, the epidemics of puerperal sepsis in the lying-in hospitals did not dramatically alter the national maternal mortality rates. Between 1775 and 1900, a total of 1720 parturients were recorded to have died from puerperal sepsis in the lying-in hospitals, which represents 2.2% of all maternal deaths during the period. It was during the second half of the 19th century, when the national statistics recorded puerperal sepsis separately, that the nationwide problem became obvious. Between 1861 and 1900, 54% of maternal deaths were caused by puerperal sepsis, most of them following home deliveries. This percentage was even higher for home deliveries before the introduction of antiseptic technique,18 possibly also caused by an increased virulence of the dominant strain of streptococcus at the time.1 The diagnosis of puerperal sepsis was probably not confounded by septic abortions during the 19th century.16

The adverse effects of medical technology were predisposing, positive risk factors. Before the introduction of antiseptic techniques, lying-in hospitals were a positive risk factor in the transmission of puerperal sepsis. As can be seen by extrapolating from the mortality rate of puerperal sepsis between 1881 and 1895 (after the introduction of antiseptic techniques), if such techniques had been available from 1776 through 1900, the number of puerperal deaths in lying-in hospitals would have been 119 instead of 1720. The difference, 1601 deaths, is a measure of the potentially adverse effects that the lying-in hospitals had on the number of maternal deaths nationwide from 1776 through 1900 (n = 76 776). However, the protective effect of these hospitals as educational centers for midwives and physicians practicing in rural areas has not been considered.16

IMPACT OF INTERVENTION

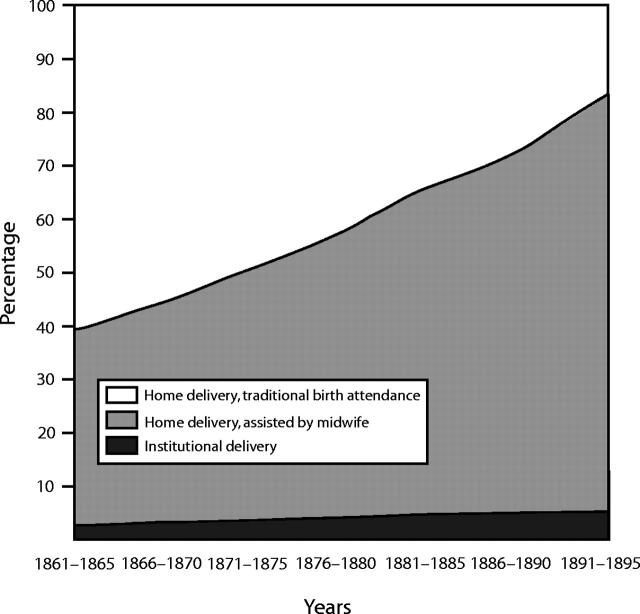

The impact of midwife-assisted delivery on maternal and child outcome is of major historical interest. At the beginning of the 19th century, almost 40% of deliveries were attended by a licensed midwife, while only a very small fraction of women gave birth in a lying-in hospital. By the end of the 19th century, 78% of parturients were attended by a licensed midwife, while only 2.8% gave birth at a lying-in hospital (Figure 1 ▶).18 The mean annual number of deliveries per midwife in the rural areas was 37 during the second half of the 19th century. The midwives used forceps in only 1 of 133 to 180 deliveries, with a case fatality rate of 27 to 39 deaths per 1000 operations.16

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of parturients in Sweden delivered by traditional birth attendants, licensed midwives, and in lying-in hospitals during the years 1861 through 1895.

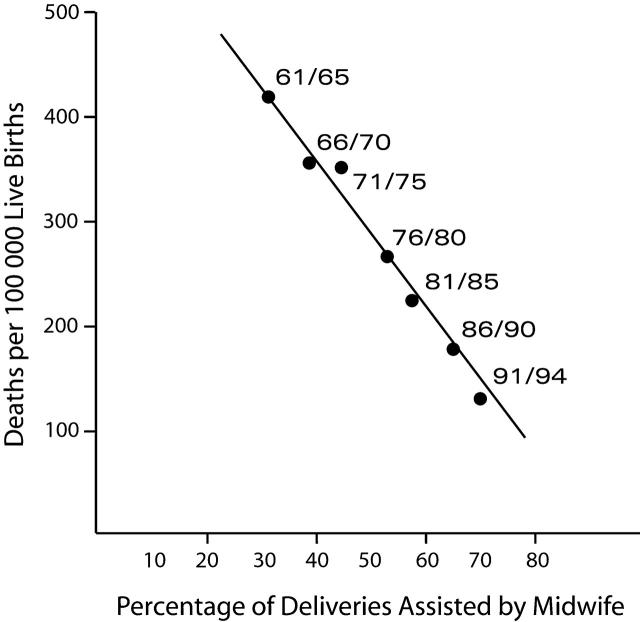

The nonseptic maternal mortality was reduced from 414 per 100 000 live births to 122 per 100 000 when the proportion of deliveries assisted by midwives in the rural areas increased from 30% to 70%. The risk of nonseptic maternal death was reduced fivefold, with a relative risk of 0.2 for midwife-assisted home deliveries. By taking the percentage of midwife-assisted deliveries, the prevented fraction for nonseptic maternal deaths associated with midwife assistance can be estimated to be 46% for the years 1861 through 1900.18

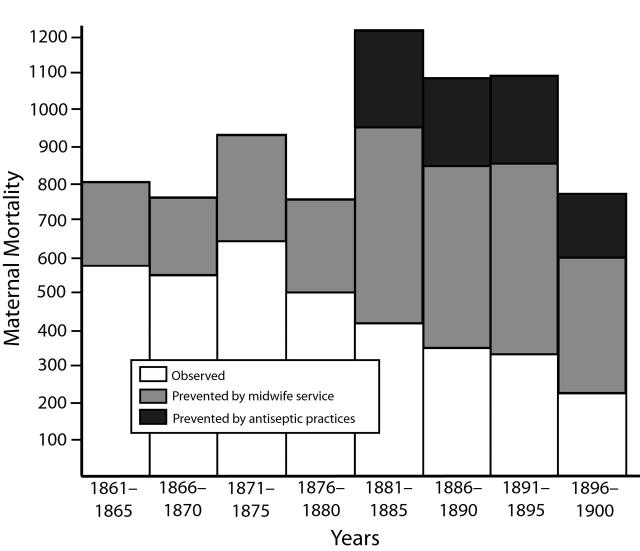

The antiseptic decree for midwife-assisted home deliveries was implemented in 1881, although the technology was successively introduced in the lying-in hospitals during the 1870s. By defining 100% exposure of the antiseptic technique, preventive fractions can be calculated. After the introduction of the antiseptic technique, the mortality rate for puerperal sepsis decreased 25-fold in the lying-in hospitals. The potential relative risk associated with the use of antiseptic technique was 0.04. This was not due to a reduced fatality of the diagnosed cases of puerperal sepsis, because half of the patients with puerperal sepsis still died, but rather to a diminished incidence of puerperal sepsis. The antiseptic technique was estimated to have “prevented” 96% of septic maternal deaths during the years 1881 through 1900, or 65% for the years 1861 through 1900.18

However, since only a minority of women at the time lived in urban areas, and since of these an even smaller proportion gave birth in lying-in hospitals, the introduction of the antiseptic technique did not prevent as many deaths in the lying-in hospitals as it did in home deliveries. The introduction of the antiseptic technique in home deliveries decreased the risk of death due to puerperal sepsis 2.7-fold (relative risk = 0.37).18 Consequently, it is estimated that 63% of the septic maternal deaths were prevented in noninstitutional deliveries in Sweden between 1881 and 1900. This result is strengthened by the steep decline of maternal mortality from the 1870s and the directly inverse association between the decline in nonseptic maternal deaths and the increase in deliveries assisted by midwives in rural areas from 1861 to 1894 (Figure 2 ▶).18 After the introduction of the antiseptic technique, puerperal sepsis mortality did not decline further until the introduction of antibiotics during the 1930s.19

FIGURE 2—

Midwifery service in rural areas in Sweden and maternal mortality (septic deaths excluded) for the years 1861 through 1894.

With the assumption that the two acted independently of each other, we can conclude that during the years 1861 through 1900, the antiseptic technique reduced mortality by puerperal sepsis by 49%, and that midwifery reduced nonseptic maternal mortality by 46% (Figure 3 ▶). The positive impact of this intervention could be interpreted in several ways. Naturally, the midwives’ skill was important, but they used forceps in fewer than 1% of the deliveries and performed destructive operations very seldom, so other factors must have been of importance. The contribution could also be interpreted in more general terms as providing care for the parturient and her prolonged labor with morphine, an enema, catheterization of the bladder, and surveillance of the third stage of labor.18 The importance of supporting the parturient is now evidence-based; continuous support during labor from caregivers reduces the likelihood of operative vaginal delivery as well as cesarean delivery and asphyxia of the child.20

FIGURE 3—

Observed number of maternal deaths per 100 000 live births and prevented number of maternal deaths by medical technology, midwifery service, and antiseptic technique in Sweden during the years 1861 through 1900 (5-year mean).

A shift in the distribution of the parturients’ age, with a smaller proportion of parturients of advanced age, contributed to only 2.9% of the decline in mortality between 1781 and 1911.21

The implementation of a Swedish midwifery service for home deliveries is probably one reason why in the early 20th century, Sweden had a lower maternal mortality rate than more prosperous countries such as Britain and the United States. The fairly centralized public welfare system in Sweden at the time may have facilitated the intervention. Despite a relatively low gross domestic product, the homogeneity of the rural areas and a rather smooth socioeconomic national development may also have contributed to the successful implementation of the system. Difficult social circumstances could impede an intervention, as illustrated in the Sundsvall sawmill area in Sweden, called “Little America” at the time owing to its very high immigration rate and reported social turmoil; no decline in maternal mortality was recorded there.17 Even so, the preventive fraction of midwifery on perinatal mortality in this area was 15% between 1881 and 1890, and 30% between 1891 and 1899.22

THE 20TH-CENTURY DECLINE IN MATERNAL MORTALITY

A phenomenon common to the industrialized countries during the first decades of the 20th century was that whereas total mortality declined, maternal mortality remained high or even increased. Maternal mortality declined exponentially and simultaneously in the Western countries from the 1930s onward, and this was indisputably due to modern obstetric care.4,13 Furthermore, modern obstetrics has been proposed to have been the main contributor to the decline in mortality, while a rise caused by poverty and associated malnutrition was purportedly only of minor importance.1

However, the view that the steep decline in Western maternal mortality rates is due only to modern obstetrics, with its blood transfusions, antibiotics, and safe operations, could be confounded by the same factors that are now impeding a worldwide maternal mortality decline. A causal inference must also take into account the fact that socioeconomic deprivation is a major factor underlying maternal mortality. One oversight in the interpretation of the Western maternal mortality decline may be that a clinical perspective would underestimate a potential cohort effect of reduced poverty and subnutrition on secular trends of maternal mortality. Obstructed labor has been one of the leading causes of maternal deaths throughout history.23 Evidently, the main reason for the reduced deaths due to obstructed labor during the 1940s in Sweden was safer deliveries. However, at the same time, a decrease in the incidence of obstructed labor was reported. This could be interpreted as an effect of the better nutritional status of infants born in the 1920s, who started having their own children during the 1940s24—the era when contracted pelvis (narrow birth canal due to nutritional deficiencies) disappeared almost entirely from obstetric practice in Western society.23

Vitamin A deficiency was a problem still affecting Swedish children in the 1930s and 1940s, and it may have created problems for parturients as well. Already in 1931, it was shown that vitamin A supplementation may reduce puerperal sepsis by as much as 70%.25 The evidence that vitamin A supplementation for women may have reduced maternal mortality by 40% in a Nepalese community,26 and a randomized trial of vitamin A supplementation in Indonesia showing a 50% reduction of puerperal fever27—probably through better resistance against infections—indicate the importance of women’s nutritional status in relation to maternal mortality.

A cautious interpretation of the Western maternal mortality decline should also take into account the concept of medical technology. These include not only clinical and therapeutic improvements but also a mobilization of human resources with regard to clinical performance and community participation.

Maternal mortality became a public health issue of great concern in the early 20th century in both England and the United States.3 The importance of the general understanding of the “road-to-death” and the introduction of the concept of “avoidability” that was presented by the British Health Ministry and White House conferences during the 1920s, as well as the establishment of confidential enquiries and maternal mortality committees with community involvement, should not be underestimated.

Regarding medical technology and reproductive health, the society’s and the larger population’s involvement should be considered as a prerequisite. Neither secondary nor tertiary prevention, nor early detection, referral, or audit procedures, would have worked in the Western countries without the socioeconomic progress of public health efforts that have taken place since the 1940s. In this respect, the decrease in maternal mortality would not have been as significant without the establishment of the welfare state in the Western countries.

CONCLUSION

The successful maternity care intervention in Sweden in the 19th century was dependent on the public health system, which was based in turn on equity and an alliance between midwives and doctors in a system of close supervision and surveillance. Even though the potential importance of community midwives was originally outlined in 1751, successful implementation had to wait until the late 19th century owing to the population’s slow acceptance of professional birth assistance, the lack of economic possibilities to subsidize a midwife in every rural county, and the absence of antiseptic technology.

The decline in Sweden’s maternal mortality rate since the 1930s parallels that in other Western countries. Medical technology was certainly a major factor, but its success was dependent on the emergence of the Western welfare state.

Figure 4.

The equipment of a home-delivering midwife in early-20th-century Sweden. Source: Jamtli Museum, Sweden

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Loudon I. Maternal mortality in the past and its relevance to developing countries today. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(1 suppl):241S–246S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Brouwere V, Tonglet R, Van Lerberghe W. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality in developing countries: what can we learn from the history of the industrialized West? Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loudon I. Death in Childbirth. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1992.

- 4.Leavitt J. Joseph B. DeLee and the practice of preventive obstetrics. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1353–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosmak G. Results of supervised midwife practice in certain European countries. JAMA. 1927;89:2009–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Högberg U. Children of Poverty—A Public Health History of Sweden [in Swedish]. Stockholm, Sweden: Liber; 1983.

- 7.Romlid C. Swedish midwives and their instruments in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In: Marland H, Rafferty AM, eds. Midwives, Society and Childbirth: Debates and Controversies in the Modern Period. London, England: Routledge; 1997:38–60.

- 8.Romlid C. Power, Resistance and Change: The History of Swedish Health Care Reflected Through the Official Midwife-System 1663–1908 [PhD thesis; English summary]. Stockholm, Sweden: Vårdförbundet; 1998.

- 9.Högberg U, Bergström E. Suffocated prone: the iatrogenic tragedy of SIDS. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:527–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brändström A. “The Loveless Mothers”: Infant Mortality in Sweden During the 19th Century With Special Attention to the Parish of Nedertorneå [PhD thesis; English summary]. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå University; 1984.

- 11.Milton L. Midwives in the Folkhem: Professionalisation of Swedish Midwifery During the Interwar and Postwar Period [PhD thesis; English summary]. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University; 2001.

- 12.Öberg L. The Midwife and the Doctor: Competence and Conflict in Swedish Maternity Care 1870–1920 [PhD thesis]. Stockholm, Sweden: Ordfront; 1996.

- 13.Thompson A. European midwifery in the inter-war years. In: Marland H, Rafferty AM, eds. Midwives, Society and Childbirth: Debates and Controversies in the Modern Period. London, England: Routledge; 1997:20–37.

- 14.Högberg U, Wall S. Secular trends in maternal mortality in Sweden from 1750 to 1980. Bull World Health Organ. 1986;64:79–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Högberg U, Brostrom G. The demography of maternal mortality—seven Swedish parishes in the 19th century. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1985; 23:489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Högberg U. Maternal Mortality in Sweden. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå University; 1986. Medical Dissertations New Series No. 156.

- 17.Andersson T, Bergstrom S, Högberg U. Swedish maternal mortality in the 19th century by different definitions: previous stillbirths but not multiparity risk factor for maternal death. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000; 79:679–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Högberg U, Wall S, Brostrom G. The impact of early medical technology on maternal mortality in late 19th century Sweden. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1986;24:251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Högberg U. Effect of introduction of sulphonamides on the incidence of and mortality from puerperal sepsis in a Swedish county hospital. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26:233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr G J, Sakala C. Continuous support for women during childbirth (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2004. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons.

- 21.Högberg U, Wall S. Age and parity as determinants of maternal mortality—impact of their shifting distribution among parturients in Sweden from 1781 to 1980. Bull World Health Organ. 1986;64:85–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersson T. Survival of Mothers and Their Offspring in 19th Century Sweden and Contemporary Rural Ethiopia [PhD thesis]. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå University; 2000.

- 23.Gebbie D. Reproductive Anthropology—Descent Through Women. Chichester, England: J. Wiley & Sons; 1981.

- 24.Högberg U, Joelsson I. The decline in maternal mortality in Sweden, 1931–1980. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1985;64:583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green H, Pindar D, Davis G, Mellanby E. Diet as a prophylactic agent against puerperal sepsis with special reference to vitamin A as an anti-infective agent. BMJ. 1931;2:595–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West KP Jr, Katz J, Khatry SK, et al. Double blind, cluster randomised trial of low dose supplementation with vitamin A or beta carotene on mortality related to pregnancy in Nepal. The NNIPS-2 Study Group. BMJ. 1999;318:570–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nurdiati D. Nutrition and Reproductive Health in Central Java, Indonesia [PhD thesis]. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå University; 2001.